Published online Jun 25, 2015. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v7.i7.720

Peer-review started: November 2, 2014

First decision: December 12, 2014

Revised: April 16, 2015

Accepted: May 16, 2015

Article in press: May 18, 2015

Published online: June 25, 2015

Processing time: 252 Days and 4.2 Hours

Although uncommon, sporadic nonampullary duodenal adenomas have a growing detection due to the widespread of endoscopy. Endoscopic therapy is being increasingly used for these lesions, since surgery, considered the standard treatment, carries significant morbidity and mortality. However, the knowledge about its risks and benefits is limited, which contributes to the current absence of standardized recommendations. This review aims to discuss the efficacy and safety of endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) and endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) in the treatment of these lesions. A literature review was performed, using the Pubmed database with the query: “(duodenum or duodenal) (endoscopy or endoscopic) adenoma resection”, in the human species and in English. Of the 189 retrieved articles, and after reading their abstracts, 19 were selected due to their scientific interest. The analysis of their references, led to the inclusion of 23 more articles for their relevance in this subject. The increased use of EMR in the duodenum has shown good results with complete resection rates exceeding 80% and low complication risk (delayed bleeding in less than 12% of the procedures). Although rarely used in the duodenum, ESD achieves close to 100% complete resection rates, but is associated with perforation and bleeding risk in up to one third of the cases. Even though literature is insufficient to draw definitive conclusions, studies suggest that EMR and ESD are valid options for the treatment of nonampullary adenomas. Thus, strategies to improve these techniques, and consequently increase the effectiveness and safety of the resection of these lesions, should be developed.

Core tip: Widespread use of endoscopy leads to increase detection of sporadic nonampullary duodenal adenomas. Due to significant morbidity and mortality of surgical treatment in this setting, endoscopic treatment with endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) or endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD), has been progressively used for the resection of these lesions. This extensive and detailed review discusses the efficacy and safety of EMR and ESD in this context. We conclude that EMR and ESD are valid options for the treatment of sporadic nonampullary duodenal adenomas. Strategies to improve these techniques, and consequently increase their effectiveness and safety should be developed.

- Citation: Marques J, Baldaque-Silva F, Pereira P, Arnelo U, Yahagi N, Macedo G. Endoscopic mucosal resection and endoscopic submucosal dissection in the treatment of sporadic nonampullary duodenal adenomatous polyps. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2015; 7(7): 720-727

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v7/i7/720.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v7.i7.720

We searched Medline (PubMed) for all published manuscript up to 2014. The search terms used were “(duodenum OR duodenal) (endoscopy OR endoscopic) adenoma resection”. The search was restricted to English language and was extended by carefully reviewing the bibliographies of the pertinent manuscripts on this subject. Of the 189 retrieved articles, and after reading their abstracts, 19 were selected due to their scientific interest. The analysis of their references, led to the inclusion of 23 more articles for their relevance in this subject.

Duodenal adenomatous polyps are a rare disease in the general population, reported as incidental findings in up to 0.1%-0.34% of the patients undergoing upper gastrointestinal endoscopy[1,2]. The evolution and widespread of this exam contributed to the increase in smaller sized polyps early diagnosis[3-5]. Adenomas are the histologic subtype that constitutes the majority of the duodenal lesions that need resection[2,6]. For this reason, they must be distinguished from non-adenomatous polyps, namely the ones that originate in the mucosa (gastric metaplasia) or submucosa (carcinoid tumors, leiomyomas, lipomas, inflammatory fibroid polyps and gastrointestinal stromal tumors), hamartomatous polyps (Brunner glands hyperplasia and Peutz-Jegher polyps, among others), and metastatic polyps[1,5,6]. One of the goals of the treatment, common to all duodenal adenomas, is the elimination of the tumoral progression risk, which correlates with the size of the lesion and is similar to that of colorectal adenomas[6,7].

These lesions are classified, according to its location, in ampullary (if they involve the duodenal bulb major - ampulla of Vater - or minor) or not ampullary. In both circumstances, they may occur as part of a genetic syndrome associated with the development of polyps, as the Familial Adenomatous Polyposis, or sporadically[8,9].

Sporadic nonampullary adenomatous polyps have similar incidence in both sexes and are mostly diagnosed accidentally between the sixth and eighth decades of life[5,6]. Typically, these lesions are solitary, with sessile or flat morphology, more than 10 mm, located in the second portion of the duodenum and asymptomatic[9-14]. However, depending on their size, location and histological characteristics, they can cause dyspepsia, abdominal pain, bleeding and bowel obstruction[5].

The traditional therapeutic approach for duodenal polyps is local surgical excision or radical surgery, respectively characterized by high rates of recurrence and significant morbidity and mortality[15,16]. In 1973, Haubrich described the first endoscopic excision of a duodenal adenoma, which, since then, has been pointed out by several publications as a safe and effective alternative to surgery[3,4,10,11,17-19]. In a retrospective analysis of 62 patients with duodenal nonampullary polyps, the morbidity of the surgical therapy was significantly superior to the one of the endoscopic resection (33% vs 2%)[20].

The use of endoscopic techniques in the duodenum is still controversial, since it represents a diagnostic and technical challenge[3,6]. The duodenum has several peculiarities that make the endoscopic resection complications risk higher than the one described elsewhere in the gastrointestinal tract[21]. Indeed, its narrow lumen and retroperitoneal fixation hampers the maintenance of an adequate vision field during the procedure[22]. On the other hand, this organ has the thinnest wall of the digestive tract and shows a thick fibrous submucosa, even in a non-pathological situation, which can limit the protrusion of the mucosa achieved by the submucosal saline injection[22].

The scientific evidence of the risks and benefits of the endoscopic treatment and its long-term outcomes in the resection of nonampullary polyps, both sporadic and associated with genetic syndromes, is limited[23,24]. This reality contributes, along with the fact that this type of lesions is infrequent and has a natural history and clinical importance that is not fully understood, to the absence of a specific set of criteria for clinical guidance[5,24,25]. Consequently, the therapeutic strategies are usually considered taking into account the patient’s condition, the characteristics of the lesion and the experience of who performs the endoscopic technique[5,7,24].

In 2010, a review published by the National Institute of Clinical Excellence highlighted the lack of published material that addressed this topic[23]. Although the number of clinical trials has increased since then, the best treatment of nonampullary adenomas remains subject of discussion[9]. The purpose of this work is to review the scientific literature regarding endoscopic resection of sporadic duodenal nonampullary adenomatous polyps, highlighting the benefits and drawbacks of EMR and ESD based on the analysis of different outcomes obtained with their practice.

Before endoscopic resection, it is essential to characterize the size of the polyp, duodenal folds and lumen extension involvement[6]. It should be ensured that it doesn’t involve the ampulla of Vater (which would imply a different diagnostic and therapeutic approach) with a side-viewing endoscope or with endoscopic ultrasound[5,6,25].

The endoscopic appearance of duodenal adenomas cannot always distinguish them safely from non-adenomatous polyps and thus, all lesions considered suspicious should be biopsied[25]. It is also important to determine the resectability of the lesion and detect any signs that suggest submucosal invasion, and that influence the treatment, such as tumors with depression (IIc in the Paris Classification), type V pit pattern classification described by Kudo, presence of bleeding, induration, ulceration or irregularities on the surface of the polyp and non-lifting sign after submucosal saline injection[5,6,26,27].

The exact role of endoscopic ultrasound in the evaluation of nonampullary adenomas remains uncertain[24]. When it’s impossible to establish the relationship of the polyp with the pancreaticobiliary tree with a forward and side-viewing endoscopy, endoscopic ultrasound is an alternative technique, obviating the need of an endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography[5]. Some researchers advocate its use in the evaluation of the depth of duodenal polyps larger than 20 mm[7,24]. However, according to Al-Kawas, the routinely use of endoscopic ultrasound, apart from not bringing great benefit, would have a considerable cost[7].

Newer techniques such as magnification endoscopy, endoscopy with narrowbanding imaging or chromoendoscopy (with a non absorbable dye such as indigo carmine) allow better delineation of the margins of the lesion and can be used in the initial evaluation of duodenal adenomas, potentially reducing incomplete resection rates[6,21]. Although there is little information regarding the use of magnification chromoendoscopy in the duodenum, this technique showed a reduction of local neoplastic recurrence from 8.7% to 0.5% when associated with EMR of flat colonic lesions bigger than 2 cm[28]. Shinoda et al[29] found that magnification endoscopy with narrowbanding imaging or indigo carmine is more accurate than endoscopic ultrasound in the evaluation of the gastric and oesophageal mucosal cancer depth. Future research will be essential for the determination of these techniques’ role in the duodenum[13].

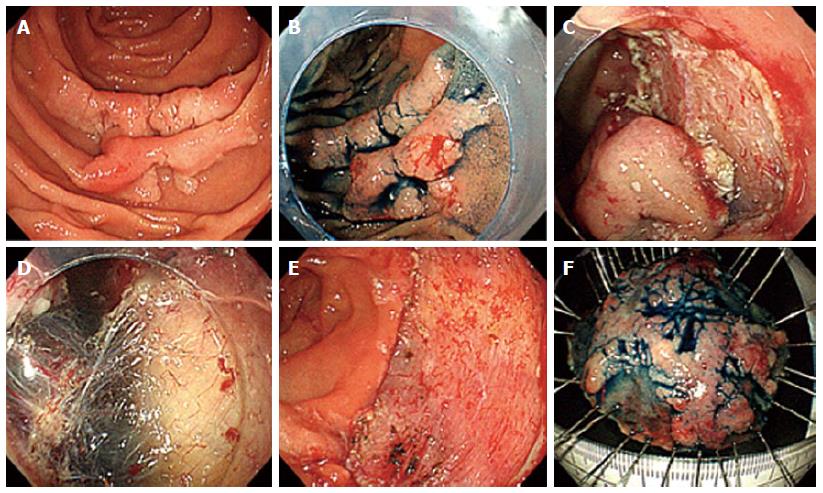

This technique was developed to remove sessile or flat tumors that are confined to the superficial layers (mucosa and submucosa) of the GI tract wall. Classically, it’s used for en bloc or piecemeal resection, if the diameter is less or more than 2 cm, respectively[30]. The lesion is initially elevated by the injection of a saline substance into the submucosa that causes its protrusion into the duodenal lumen. Depending on the size of the polyp, the volume of injected solution can vary between 5 and 50 mL, and it may be necessary to repeat this procedure if the cushion created by the injected fluid dissipates before the resection is complete[30]. There are several solutions currently available, but isotonic saline (0.9% NaCl) is the most frequently used[30]. However, scientific evidence suggests that hypertonic solutions originate a better and longer-lasting elevation[6,31]. This procedure allows the isolation of the mucosa involved, facilitating its resection with an endoscopic snare, and reduces the risk of thermal and mechanical injury of the deepest layers. The non-lifting sign enables the identification of polyps that are likely to have submucosal invasion, and that don’t usually have an indication for endoscopic treatment[6,19,31]. The inclusion of adrenaline in the injected solution reduces the haemorrhagic risk and provides better visibility[6]. As a diagnostic tool, and differently from ablative therapy, it holds an important role in obtaining samples for histological analysis[31]. When compared to snare or forceps polypectomy, EMR allows resection of a larger area, as well as access to deeper levels, through the excision of the medium or deep submucosal layer[31]. It thus facilitates histological assessment of the entire lesion and thereby identifies foci of malignancy that cannot be included in the surface sample obtained by forceps or snare biopsy[18] (Figure 1).

The predominantly retrospective published clinical trials report an EMR complete resection rate of nonampullary adenomas of 79%-100%[4,10-14,18,19,32,33]. In the studies that indicate the type of resection, it appears that in 64% of the cases it was possible to remove the polyp en bloc, having the remaining been excised with piecemeal resection[4,10,12,13,18,32-35]. The latter is more frequent in lesions larger than 20 mm, hardly removed safely en bloc, and seems to be associated with higher rates of recurrence and residual lesion[13,18,19,33]. The execution of the technique is a critical factor in minimizing these potential risks[19].

Kedia et al[12] studied the relationship between the adenomatous polyp size, the extent of duodenal lumen involved, and the efficacy of EMR. He concluded that although there is a significant association between the proportion of duodenal lumen involved and complete endoscopic resection, the same doesn’t happen between the latter and the size of the lesion. The complete resection rate achieved in tumors involving less than one quarter of the luminal circumference was 94.7%, compared to 45.5% in those involving one quarter to half of the circumference. In lesions where more than half of the luminal circumference was involved no lesion was resected successfully. Thus, this author suggests that the strongest clinical predictor of a successful polyp excision is the luminal extension that it involves. The American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE) guidelines indicate that surgery should be considered in adenomas involving more than 33% of the circumference of the lumen[24].

In the studies that report the number of sessions required to achieve complete resection, 80% of the cases it was possible with one session, 17% with two sessions and only 3% in three sessions[6]. In all situations, the purpose of who performs the EMR should be to remove the entire polyp in one session, without compromise of security[21]. Areas with residual adenoma and fibrosis are more difficult to resect during subsequent interventions, which are associated with increased risk of complications[6,9,21].

The recurrence rate varies widely between 0% and 36%, and all described recurrent lesions were treated with polypectomy snare or ablative therapy[6,9,13,18,19,36]. This high rate reinforces the need of a detailed resection of all adenomatous tissue, possibly with use of adjuvant therapy, and a rigorous follow-up period, especially in larger adenomas or with piecemeal resection[6,12,19].

Bleeding, which is associated with duodenal abundant vascularization, occurs during EMR (immediate bleeding) in 9% of procedures[6]. As there is no standardized definition of immediate haemorrhage, it’s hard to know whether the reported cases were clinically significant or had comparable gravity. However, Lepilliez et al[18] does not consider it a true complication, since it can often be controlled by application of endoscopic clips, using ablative therapy or adrenaline injection adrenaline. None of the described cases needed blood transfusion[3,4,6,10,11,18,19].

Late bleeding rate ranges from 0 to 12%[1,4,10,12,13,18,19,33]. A recent study, that included 50 nonampullary adenomas, showed that the risk of delayed haemorrhage is significantly higher in lesions which diameter was bigger than 30 mm[35]. In all cases, bleeding occurred within the first 48 h after resection and was mostly approached conservatively or with endoscopic mono or bipolar electrocautery, epinephrine injection, haemostatic clips or a combination of these[1,4,10,12,13,18,19,33].

The proceeding method regarding the presence of visible non-bleeding vessels and the closure of the resected area as a preventive measure of late haemorrhage, are questions that don’t gather a consensus answer[35]. Kim et al[13] defends that primary closure with clips is preferable to ablative therapy, since it does not increase the risk of tissue injury. Although closure of primary defects smaller than 2 cm is usually possible, it will probably be unnecessary, except in cases where there is potential risk of late bleeding[35]. On the other hand, areas bigger than 2 cm cannot be safely closed because of the difficulty in opposing margins of the defect[13,18,35]. In the study of Lépilliez et al[18], the difference found between late haemorrhage rate of the cases that had haemorrhagic prevention systematically done (with ablative therapy or clips) or bleeding treatment was required during the procedure, and cases that didn’t have bleeding prevention or immediate haemorrhage occurred, was statistically significant. In the first group, consisting of 14 patients, there was no late haemorrhage, while in the second 5 bleedings occurred in 23 patients (22%).

EMR has a perforation risk of the duodenal wall of 0.6%[6,35]. Registered perforations were managed with endoscopy or surgery conversion[18,35]. Resection limited to the adenomas that lifted after the submucosal injection may be a way of preventing this complication[36].

This technique is widely used for en bloc resection of gastrointestinal lesions[5]. Despite its growing use in the stomach, colon and oesophagus, its use in the duodenum is less frequent[37]. This fact is probably due to its retroperitoneal fixation, thin wall and narrow lumen, which make the intervention at this location technically difficult[14,29]. The low prevalence of duodenal lesions may be one of reasons that can explain the ESD long learning curve in the duodenum[14]. The published studies that performed this technique are few and include a small number of patients with short follow-up periods[14,29,33,38,39].

ESD is generally performed in several stages. After marking the margins of the lesion, by electrocauterization, and lifting it by submucosal injection, a circumferential incision is made in this layer, and the lesion is dissected from the underlying layers by using dissection knives[30] (Figure 2).

Complete resection rate of sporadic adenomatous nonampullary polyps by ESD ranges from 86% to 100%[14,22,29,33,38,39]. No recurrence was described[14,22,33,38,39]. The choice of ESD instead of piecemeal EMR may be a way of reducing the recurrence associated with this last technique[13].

In a study by Honda et al[14], in which 15 non ampullary adenomas were resected by endoscopy (9 by ESD and the rest by EMR), found that the average diameter of the lesions removed by ESD was 24 mm (the largest lesion had 39 mm), and that those removed by EMR had an average size of 8 mm. The mean time of the interventions was also registered. ESD and EMR procedures took respectively 85 and 16 min in average. The inclusion of larger and more challenging lesions, as well as duodenal more difficult haemostasis in duodenum, are possible explanations given by the author for the time consumed by ESD.

Obtaining en bloc resection with negative margins is a well-known ESD advantage[40]. According to Endo et al[33], ESD should be the procedure of choice for lesions larger than 10 mm, and when it is desirable to obtain en bloc resection (including lesions whose biopsy or magnification endoscopy are suggestive of carcinoma). In their study, all adenomas larger than 10 mm resected by EMR revealed positive margins. All adenomas resected by ESD had negative margins (the biggest lesion diameter was 30 mm).

In three clinical trials, ESD was associated with a bleeding rate between 8% and 22%[14,22,41]. All cases were managed with endoscopic haemostatic clips, without requiring blood transfusion. The reported duodenal perforation rate is 31%[14,22,33,38,39]. This percentage is higher than the one obtained in the oesophagus, stomach and colon, and is associated to the anatomical peculiarities of the duodenum[22]. Duodenal perforation may have a difficult approach and contribute to increased morbidity and mortality of the patient, hospitalization period and health care costs[40].

Late perforation is a very serious complication that, according to a retrospective study published in 2013, is significantly associated with the endoscopic technique that was used and the location of the lesion[41]. In this study, that included lesions resected by EMR or ESD, all late perforations occurred after ESD or piecemeal EMR, which according to the authors, may be due to electrocautery overloading. It was also found that all perforations were distal to the ampulla of Vater, which seems to happen because of the proteolysis or chemical irritation caused by exposure of the duodenal wall to the pancreatic juice and bile enzymes, which can be decreased with the administration of protease inhibitors[14,39]. Given that there are several factors that may be associated with perforations, it is difficult to clarify which ones are more likely to relate to their origin[22]. Jung suggests that ESD is itself a perforation risk factor and, therefore, it should be performed only in selected patients[39]. The most appropriate prophylactic intervention and approach to late perforation in the duodenum have not been established yet[41].

The guidelines published by the ASGE emphasize that all patients who have undergone endoscopic resection of a sporadic duodenal adenoma should be considered for a follow-up program for the detection and treatment of any recurrence[24]. However, because of the lack of information, formal recommendations regarding surveillance intervals have not been defined. These should be applied on a patient-basis adjusted on the characteristics of the polyp, adequacy of the initial resection, eventual occurrence of complications and comorbidities of the patient[22]. According to a review article, most authors recommended a follow-up endoscopy 3-6 mo after resection, followed by surveillance endoscopies each 6 to 12 mo[6].

Analysis of the literature on this topic reveals a reduced number of reviews and studies, that generally include a small sample of patients and short follow-up periods, which hinders drawing consistent conclusions about the endoscopic resection long-term effectiveness of sporadic nonampullary adenomas[13,19,26,34]. Some of the results obtained in clinical trials exhibit considerable variability, which doesn’t have a clear justification, but may be associated, for example, to inconsistencies in outcome definitions by different authors, as well as the length of the follow-up period[7]. Moreover, most studies have a retrospective character, which can introduce selection bias and underestimate the complication rate[34].

Although most of the analysed studies and endoscopic techniques mentioned in this review were predominantly developed in Asian countries, it is important to note that this reality may not reflect the Western context[6]. After comparing these two populations, Min et al[34] states that Western studies show a lower complete resection rate, and suggests that this discrepancy can be clarified by the smaller sized lesions included in Asian studies, since the diagnosis of smaller adenomas has increased in these countries due to gastric cancer screening programs and subsequent widespread of the endoscopy[12,18,19,34]. Local recurrence rates are higher in Western countries, which again may be explained not only by the difference in the lesions size, but also by the follow-up period after resection, that seems to be shorter in Asia (6-29 mo vs 13-71 mo)[34]. Authors, however, rarely address this divergence.

EMR is an alternative to surgery in patients with less invasive superficial duodenal adenomas, entailing shorter hospital in-stay, lower costs, and providing a reasonable complication rate that can usually be controlled by endoscopy[13]. Resection is most likely to be complete in adenomas involving less than half of the luminal circumference[12]. It requires a tight monitoring period, especially after big adenomas or piecemeal resection, so that early detection and treatment of residual or recurrent lesions is possible[6,13]. ESD, although potentially providing en bloc resection with negative margins, has higher haemorrhagic and perforation risks in the duodenum when compared to EMR[9]. Therefore, when choosing the appropriate endoscopic technique, the risks of the procedure must be balanced against its benefits[40].

Although the scientific evidence level in this area is limited, the results obtained in these last years are encouraging. However, prospective studies with larger samples and extended follow-up periods will be necessary. Future development of techniques and tools that contribute to the prevention and early detection of recurrence, and increase the efficacy and safety of endoscopic resection in the duodenum, will be essential for a better therapeutic approach to these patients.

P- Reviewer: de Lange T, Gurkan A, Hu H S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wu HL

| 1. | Conio M, De Ceglie A, Filiberti R, Fisher DA, Siersema PD. Cap-assisted EMR of large, sporadic, nonampullary duodenal polyps. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;76:1160-1169. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Jepsen JM, Persson M, Jakobsen NO, Christiansen T, Skoubo-Kristensen E, Funch-Jensen P, Kruse A, Thommesen P. Prospective study of prevalence and endoscopic and histopathologic characteristics of duodenal polyps in patients submitted to upper endoscopy. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1994;29:483-487. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 125] [Cited by in RCA: 142] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Oka S, Tanaka S, Nagata S, Hiyama T, Ito M, Kitadai Y, Yoshihara M, Haruma K, Chayama K. Clinicopathologic features and endoscopic resection of early primary nonampullary duodenal carcinoma. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2003;37:381-386. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Hirasawa R, Iishi H, Tatsuta M, Ishiguro S. Clinicopathologic features and endoscopic resection of duodenal adenocarcinomas and adenomas with the submucosal saline injection technique. Gastrointest Endosc. 1997;46:507-513. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Culver EL, McIntyre AS. Sporadic duodenal polyps: classification, investigation, and management. Endoscopy. 2011;43:144-155. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Basford PJ, Bhandari P. Endoscopic management of nonampullary duodenal polyps. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2012;5:127-138. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Al-Kawas FH. The significance and management of nonampullary duodenal polyps. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y). 2011;7:329-332. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Bülow S, Bülow C, Nielsen TF, Karlsen L, Moesgaard F. Centralized registration, prophylactic examination, and treatment results in improved prognosis in familial adenomatous polyposis. Results from the Danish Polyposis Register. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1995;30:989-993. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Basford PJ, George R, Nixon E, Chaudhuri T, Mead R, Bhandari P. Endoscopic resection of sporadic duodenal adenomas: comparison of endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) with hybrid endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) techniques and the risks of late delayed bleeding. Surg Endosc. 2014;28:1594-1600. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Apel D, Jakobs R, Spiethoff A, Riemann JF. Follow-up after endoscopic snare resection of duodenal adenomas. Endoscopy. 2005;37:444-448. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Ahmad NA, Kochman ML, Long WB, Furth EE, Ginsberg GG. Efficacy, safety, and clinical outcomes of endoscopic mucosal resection: a study of 101 cases. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;55:390-396. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 273] [Cited by in RCA: 271] [Article Influence: 11.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Kedia P, Brensinger C, Ginsberg G. Endoscopic predictors of successful endoluminal eradication in sporadic duodenal adenomas and its acute complications. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;72:1297-1301. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Kim HK, Chung WC, Lee BI, Cho YS. Efficacy and long-term outcome of endoscopic treatment of sporadic nonampullary duodenal adenoma. Gut Liver. 2010;4:373-377. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Honda T, Yamamoto H, Osawa H, Yoshizawa M, Nakano H, Sunada K, Hanatsuka K, Sugano K. Endoscopic submucosal dissection for superficial duodenal neoplasms. Dig Endosc. 2009;21:270-274. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 97] [Cited by in RCA: 116] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Galandiuk S, Hermann RE, Jagelman DG, Fazio VW, Sivak MV. Villous tumors of the duodenum. Ann Surg. 1988;207:234-239. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 107] [Cited by in RCA: 105] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Farnell MB, Sakorafas GH, Sarr MG, Rowland CM, Tsiotos GG, Farley DR, Nagorney DM. Villous tumors of the duodenum: reappraisal of local vs. extended resection. J Gastrointest Surg. 2000;4:13-21, discussion 22-23. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Haubrich WS, Johnson RB, Foroozan P. Endoscopic removal of a duodenal adenoma. Gastrointest Endosc. 1973;19:201. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Lépilliez V, Chemaly M, Ponchon T, Napoleon B, Saurin JC. Endoscopic resection of sporadic duodenal adenomas: an efficient technique with a substantial risk of delayed bleeding. Endoscopy. 2008;40:806-810. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 99] [Cited by in RCA: 113] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Alexander S, Bourke MJ, Williams SJ, Bailey A, Co J. EMR of large, sessile, sporadic nonampullary duodenal adenomas: technical aspects and long-term outcome (with videos). Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;69:66-73. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 107] [Cited by in RCA: 121] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Perez A, Saltzman JR, Carr-Locke DL, Brooks DC, Osteen RT, Zinner MJ, Ashley SW, Whang EE. Benign nonampullary duodenal neoplasms. J Gastrointest Surg. 2000;7:536-541. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Bourke MJ. Endoscopic resection in the duodenum: current limitations and future directions. Endoscopy. 2013;45:127-132. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Hoteya YN, Iizuka T, Kikuchi D, Mitani T, Matsui A, Ogawa O, Yamashita S, Furuhata T, Yamada A, Kimura R. Endoscopic submucosal dissection for nonampullary large superficial adeno-carcinoma/adenoma of the duodenum: feasibility and long-term outcomes. Endoscopy. International Open. 2013;E2-E7. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Hoteya YN; NICE. Endoscopic mucosal resection and endoscopic submucosal dissec-tion of non-ampullary duodenal lesions. 2010; Available from: http://www.nice.org.uk/ipg359. |

| 24. | Adler DG, Qureshi W, Davila R, Gan SI, Lichtenstein D, Rajan E, Shen B, Zuckerman MJ, Fanelli RD, Van Guilder T. The role of endoscopy in ampullary and duodenal adenomas. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;64:849-854. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 132] [Cited by in RCA: 105] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Waye JD, Barkun A, Goh KL, Novis B, Ogoshi K, Shim CS, Tanaka M. Approach to benign duodenal polyps. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;55:962-963. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | The Paris endoscopic classification of superficial neoplastic lesions: esophagus, stomach, and colon: November 30 to December 1, 2002. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;58:S3-43. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1117] [Cited by in RCA: 1327] [Article Influence: 60.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 27. | Kudo S, Hirota S, Nakajima T, Hosobe S, Kusaka H, Kobayashi T, Himori M, Yagyuu A. Colorectal tumours and pit pattern. J Clin Pathol. 1994;47:880-885. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 500] [Cited by in RCA: 473] [Article Influence: 15.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 28. | Hurlstone DP, Cross SS, Brown S, Sanders DS, Lobo AJ. A prospective evaluation of high-magnification chromoscopic colonoscopy in predicting completeness of EMR. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;59:642-650. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Shinoda M, Makino A, Wada M, Kabeshima Y, Takahashi T, Kawakubo H, Shito M, Sugiura H, Omori T. Successful endoscopic submucosal dissection for mucosal cancer of the duodenum. Dig Endosc. 2010;22:49-52. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Kantsevoy SV, Adler DG, Conway JD, Diehl DL, Farraye FA, Kwon R, Mamula P, Rodriguez S, Shah RJ, Wong Kee Song LM. Endoscopic mucosal resection and endoscopic submucosal dissection. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;68:11-18. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 236] [Cited by in RCA: 220] [Article Influence: 12.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Uraoka T, Saito Y, Yamamoto K, Fujii T. Submucosal injection solution for gastrointestinal tract endoscopic mucosal resection and endoscopic submucosal dissection. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2009;2:131-138. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Sohn JW, Jeon SW, Cho CM, Jung MK, Kim SK, Lee DS, Son HS, Chung IK. Endoscopic resection of duodenal neoplasms: a single-center study. Surg Endosc. 2010;24:3195-3200. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Endo M, Abiko Y, Oana S, Kudara N, Chiba T, Suzuki K, Koizuka H, Uesugi N, Sugai T. Usefulness of endoscopic treatment for duodenal adenoma. Dig Endosc. 2010;22:360-365. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Min YW, Min BH, Kim ER, Lee JH, Rhee PL, Rhee JC, Kim JJ. Efficacy and safety of endoscopic treatment for nonampullary sporadic duodenal adenomas. Dig Dis Sci. 2013;58:2926-2932. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Fanning SB, Bourke MJ, Williams SJ, Chung A, Kariyawasam VC. Giant laterally spreading tumors of the duodenum: endoscopic resection outcomes, limitations, and caveats. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;75:805-812. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Abbass R, Rigaux J, Al-Kawas FH. Nonampullary duodenal polyps: characteristics and endoscopic management. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;71:754-759. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 91] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Oka S, Tanaka S, Kaneko I, Mouri R, Hirata M, Kawamura T, Yoshihara M, Chayama K. Advantage of endoscopic submucosal dissection compared with EMR for early gastric cancer. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;64:877-883. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 487] [Cited by in RCA: 527] [Article Influence: 27.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Takahashi T, Ando T, Kabeshima Y, Kawakubo H, Shito M, Sugiura H, Omori T. Borderline cases between benignancy and malignancy of the duodenum diagnosed successfully by endoscopic submucosal dissection. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2009;44:1377-1383. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Jung JH, Choi KD, Ahn JY, Lee JH, Jung HY, Choi KS, Lee GH, Song HJ, Kim DH, Kim MY. Endoscopic submucosal dissection for sessile, nonampullary duodenal adenomas. Endoscopy. 2013;45:133-135. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 104] [Article Influence: 8.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Perumpail R, Friedland S. Treatment of nonampullary sporadic duodenal adenomas with endoscopic mucosal resection or ablation. Dig Dis Sci. 2013;58:2751-2752. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Inoue T, Uedo N, Yamashina T, Yamamoto S, Hanaoka N, Takeuchi Y, Higashino K, Ishihara R, Iishi H, Tatsuta M. Delayed perforation: a hazardous complication of endoscopic resection for non-ampullary duodenal neoplasm. Dig Endosc. 2014;26:220-227. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 114] [Cited by in RCA: 136] [Article Influence: 12.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |