Published online Jun 10, 2015. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v7.i6.659

Peer-review started: August 21, 2014

First decision: September 28, 2014

Revised: February 6, 2015

Accepted: March 5, 2015

Article in press: March 9, 2015

Published online: June 10, 2015

Processing time: 303 Days and 20.5 Hours

AIM: To evaluate the determination of the margin of differentiated-type early gastric cancers by using conventional endoscopy.

METHODS: We retrospectively evaluated 364 differentiated early gastric cancers that were endoscopically resected as en-bloc specimens and diagnosed pathologically in detail between November 2007 and October 2008. All procedures were done with conventional endoscopes and all endoscopic samples, before and after indigo carmine dye, were re-evaluated using a digital filing system by one endoscopist. We analyzed the incidence of lesions with unclear margins and the relationship between unclear margins and relevant clinicopathological findings.

RESULTS: The rate of lesions with unclear margins was 20.6% (75/364). Multivariate regression analysis suggested that the factors that make the determination of the margin difficult were normal color, presence of components of flat area (0-IIb), a diameter ≥ 21 mm, ulceration, and components of poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma in the mucosal surface.

CONCLUSION: As many as 20% of differentiated early gastric cancers show unclear margins. Consideration of the factors associated with unclear margins may help endoscopists to accurately determine the margins of the lesion.

Core tip: As many as 20% of differentiated early gastric cancers show unclear margins by using conventional endoscopy. Consideration of the factors associated with unclear margins, such as normal color, presence of components of flat area (0-IIb), a diameter ≥ 21 mm, ulceration, and components of poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma in the mucosal surface, may help endoscopists to accurately determine the margins of the lesion.

- Citation: Yoshinaga S, Oda I, Abe S, Nonaka S, Suzuki H, Takisawa H, Taniguchi H, Saito Y. Evaluation of the margins of differentiated early gastric cancer by using conventional endoscopy. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2015; 7(6): 659-664

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v7/i6/659.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v7.i6.659

Since Gotoda et al[1] described the incidence of lymph node metastasis from early gastric cancer and with the development of endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD), early gastric cancer is often resected endoscopically. When endoscopic resection of early gastric cancers is performed, it is important to accurately determine the margin of the lesion. A vague determination of the location of the margin may allow residual cancer to remain, leading to recurrences and additional resections. Recently, imaged enhanced endoscopy (IEE) procedures, such as narrow band imaging (NBI), auto fluorescence imaging (AFI), or flexible spectral imaging color enhancement (FICE) have been developed; however, these methods have not been adopted everywhere. Therefore, an accurate understanding of the use of conventional endoscopes is still relevant.

In this study, we evaluated the determination of the margin of differentiated-type early gastric cancers by using conventional endoscopes and investigated the factors that may make the margin unclear.

A total of 381 differentiated early gastric cancers were resected endoscopically between November 2007 and October 2008. We excluded 17 early gastric cancers that could not be evaluated in detail because of piecemeal resection, severe burning effects, or other confounding factors. A total of 364 early gastric cancers were included in this study. We reviewed the clinical records, endoscopic images, endoscopy reports, and pathology reports for every patient and analyzed the incidence of lesions with unclear margins and the relationship between unclear margins and the following clinicopathological findings: age, sex, tumor location, tumor color, macroscopic type, component of flat area, tumor size, ulcer finding, component of poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma in the mucosal surface, and intestinal metaplasia around the lesion.

All patients drank a solution containing 40000 units of pronase (Pronase MS®; Kaken Pharmaceutical Products, Tokyo, Japan), 4 mL of 2% dimethicone (Gascon®; Kissei Pharmaceutical Co., Tokyo, Japan) and 2 g of NaHCO3 to dissolve mucus and bubbles before examination. All procedures were done with conventional endoscopes (GIF-Q240, Q260, H260; Olympus Optical Co., Tokyo, Japan) and without magnifying endoscopy, NBI, or AFI. All endoscopic images were recorded by using a digital filing system (NEXUS; Fuji Film Medical Co., Tokyo, Japan). All endoscopic images before and after indigo carmine dye (0.2%) were reviewed in this study by using a digital filing system by one individual (S.Y) who has 10 years of experience as an endoscopist.

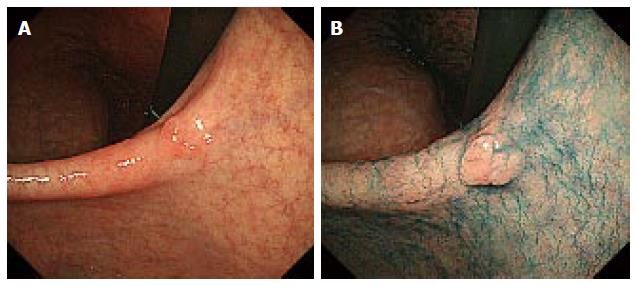

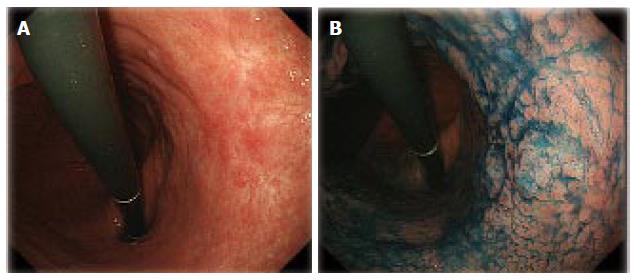

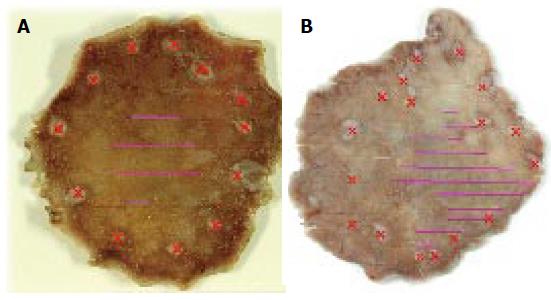

Lesions with an unclear margin were defined as lesions with an undelineated margin or an inaccurate marking. An undelineated margin was determined by reviewing the endoscopic images. The identification by the endoscopist of a difference between the lesion and surrounding mucosa in terms of colors, surface morphology, and a height more than two-thirds the size of the circumference was considered a delineated margin (Figure 1). If it was not possible to make a distinction, it was classified as an undelineated margin lesion (Figure 2). We also evaluated the markings made before resection to recognize the tumor margin. We defined an accurate marking if all markings were made outside of the tumor in the resected specimen (Figure 3A). If not, we defined it as an inaccurate marking (Figure 3B). The tumor color and location were also determined endoscopically. The stomach is anatomically divided into three parts: the upper third (U), middle third (M), and lower third (L). The cross-sectional circumference of the stomach is divided into four equal parts; the lesser and greater curvatures, and the anterior and posterior walls based on the Japanese Classification of Gastric Carcinoma[2]. The main macroscopic type of the tumor was classified based on the Paris classification[3], and the components of flat area (0-IIb) of the tumor, tumor size, ulceration findings, components of poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma in the mucosal surface, and metaplasia around the tumor were determined histopathologically.

Statistical analysis were made by using the Student’s t test for evaluating the patients’ ages and the tumor sizes, and by using the χ2 test with Yate’s correction and the Fisher exact test for evaluating any other factors. A level of P < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. After evaluating the factors that made the determination of the margin difficult, we decided to use logistic regression analysis for further analysis of those factors.

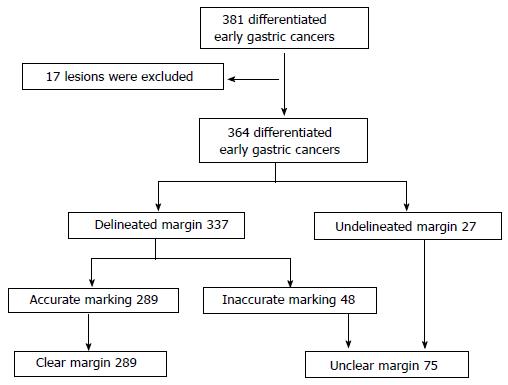

The characteristics of the 364 candidate lesions reviewed during this period are described in Table 1. There were 27 undelineated margin lesions and 337 delineated margin lesions. There were 62 lesions with inaccurate markings and 302 lesions with accurate markings (Table 1). Consequently, 14 lesions were found to have overlapping results. Therefore, there were 75 lesions with unclear margins (Figure 4). The rate of those lesions in this group was 20.6% (75/364).

| Age (yr) | |

| Median ± SD | 70 ± 9 |

| Range | 30-92 |

| Sex | |

| Men (%) | 293 (80.5) |

| Women (%) | 71 (19.5) |

| Tumor location (three parts) | |

| U (%) | 74 (20.3) |

| M (%) | 144 (39.6) |

| L (%) | 146 (40.1) |

| Tumor location (cross-sectional parts) | |

| Less (%) | 140 (38.5) |

| Gre (%) | 59 (16.2) |

| Ant (%) | 64 (17.6) |

| Post (%) | 101 (27.7) |

| Color | |

| Reddish (%) | 213 (58.5) |

| Discolored (%) | 87 (23.9) |

| Normal color (%) | 64 (17.6) |

| Margin of the lesion | |

| Delineated | 337 (92.6) |

| Undelineated | 27 (7.4) |

| Main macroscopic type | |

| 0-I (%) | 11 (3.0) |

| 0-IIa (%) | 154 (42.3) |

| 0-IIb (%) | 6 (1.6) |

| 0-IIc (%) | 193 (53.0) |

| Components of flat area (0-IIb) | |

| Presence (%) | 17 (4.7) |

| Absense (%) | 347 (95.3) |

| Tumor size (mm) | |

| Median ± SD | 16 ± 13 |

| Range | 2-100 |

| Ulceration finding | |

| Presence (%) | 62 (17.0) |

| Absense (%) | 302 (83.0) |

| Components of poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma in the mucosal surface | |

| Presence (%) | 26 (7.1) |

| Absense (%) | 338 (92.9) |

| Metaplasia around the lesion | |

| Presence (%) | 337 (92.6) |

| Absense (%) | 27 (7.4) |

| Marking | |

| Right | 302 (83.0) |

| Wrong | 62 (17.0) |

Factors that had significant correlations with unclear margins were tumor location (three parts), color, components of the flat area (0-IIb), tumor size, ulceration, and components of poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma in the mucosal surface (Table 2). After evaluating those 6 factors by multivariate regression analysis, the factors that made the determination of the margin difficult were normal coloration (OR = 2.095; 95%CI: 1.040-4.217; P = 0.0383), components of flat area (0-IIb) (OR = 4.900; 95%CI: 1.610-14.913; P = 0.0051), the diameter ≥ 21 mm (OR = 3.852; 95%CI: 2.165-6.852; P < 0.0001), ulceration findings (OR = 2.307; 95%CI: 1.156-4.604; P = 0.0178), and components of poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma in the mucosal surface (OR = 6.650; 95%CI: 2.590-17.073; P < 0.0001) (Table 3).

| Clear margin (n = 289) | Unclear margin (n = 75) | ||

| Age (yr) | |||

| Median ± SD | 70 ± 8 | 72 ± 10 | NS |

| Range | 37-92 | 30-90 | |

| Sex | |||

| Men (%) | 237 (82.0) | 56 (74.7) | NS |

| Women (%) | 52 (18.0) | 19 (25.3) | |

| Tumor location (three parts) | |||

| U (%) | 54 (18.7) | 20 (26.7) | P= 0.0128 |

| M (%) | 108 (37.4) | 36 (48.0) | |

| L (%) | 127 (43.9) | 19 (25.3) | |

| Tumor location (cross-sectional parts) | |||

| Less (%) | 113 (39.1) | 27 (36.0) | NS |

| Gre (%) | 47 (16.3) | 12 (16.0) | |

| Ant (%) | 51 (17.6) | 13 (17.3) | |

| Post (%) | 78 (27.0) | 23 (30.7) | |

| Color | |||

| Reddish (%) | 165 (57.1) | 48 (64.0) | P= 0.0049 |

| Discolored (%) | 79 (27.3) | 8 (10.7) | |

| Norm-colored (%) | 45 (15.6) | 19 (25.3) | |

| Main macroscopic type | |||

| 0-I (%) | 10 (3.5) | 1 (1.3) | NS |

| 0-IIa (%) | 120 (41.5) | 34 (45.3) | |

| 0-IIb (%) | 3 (1.0) | 3 (4.0) | |

| 0-IIc (%) | 156 (54.0) | 37 (49.3) | |

| Components of flat area (0-IIb) | |||

| Presence (%) | 7 (2.4) | 10 (13.3) | P= 0.0002 |

| Absense (%) | 282 (97.6) | 65 (86.7) | |

| Tumor size (mm) | |||

| Median ± SD | 15 ± 11 | 25 ± 17 | P< 0.0001 |

| Range | 2-68 | 3-100 | |

| Ulceration finding | |||

| Presence (%) | 43 (14.9) | 19 (25.3) | P= 0.0319 |

| Absense (%) | 246 (85.1) | 56 (74.7) | |

| Components of poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma in the mucosal surface | |||

| Presence (%) | 11 (3.8) | 15 (20.0) | P< 0.0001 |

| Absense (%) | 278 (96.2) | 60 (80.0) | |

| Metaplasia around the lesion | |||

| Presence (%) | 266 (92.0) | 71 (94.7) | NS |

| Absense (%) | 23 (8.0) | 4 (5.3) | |

| Factors | OR | 95%CI | P value |

| Lcation in the U and M parts | 1.769 | 0.940-3.331 | NS |

| Norm-colored | 2.095 | 1.040-4.217 | 0.0383 |

| Components of flat area (0-IIb) | 4.900 | 1.610-14.913 | 0.0051 |

| Tumor size ≥ 21 mm | 3.852 | 2.165-6.852 | < 0.0001 |

| Ulceration finding | 2.307 | 1.156-4.604 | 0.0178 |

| Components of poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma in the mucosal surface | 6.65 | 2.590-17.073 | < 0.0001 |

After ESD was developed, early gastric cancer was often resected endoscopically, especially in Japan. Previously reported[4-6] accuracy rates for the delineation of the margin by using conventional endoscopy were almost 80% to 85%, although the criteria for the determination of the margin were not commonly specified in those reports. In this study, we defined the accuracy rate not only by endoscopic images but also by pathological study of the specimens, and the accuracy rate was almost the same as that shown in previous reports. Asada-Hirayama et al[7] reported a similar study to ours, and in their result, the accuracy rate for the delineation of the margin was 92.6%, which was much higher than that seen in previous reports, including our study. However, they evaluated only markings on the resected specimens and they used not only conventional endoscopes, but also magnifying endoscopes with NBI. Although there was no significant difference in the accuracy between the 2 kinds of endoscopes in their study, this factor might have influenced the margin delineation rates.

Tanabe et al[6] reported the factors that make the delineation of the margin difficult as (1) large lesions (> 31 mm); (2) flat lesions or those with a flat area; (3) adenocarcinoma with low-grade atypia; (4) gastric mucin phenotype (G-type) adenocarcinoma or gastric predominant gastric and intestinal mucin phenotype (G > I-type) adenocarcinoma; and (5) carcinoma cells invading the middle to deeper portion of the mucosa under normal covering epithelium. In our study, 2 factors, lesion size and flat area, were almost the same as the factors that Tanabe et al[6] reported, and Asada-Hirayama et al[7] reported similar results. To achieve a complete resection, we should observe for those factors that demonstrate a more difficult to differentiate margin, and if the lesion might have such characteristics, we should examine the margin more carefully to ensure an accurate determination. Conventional endoscopy can demonstrate the tumor size and ulceration findings, but sometimes it is difficult to identify components of the flat area. To solve this difficulty, IEE, such as a magnifying endoscope, NBI[8,9], FICE[10], and an acetic acid-indigo carmine mixture (AIM)[11], might be useful. Yao et al[8] reported magnifying endoscopy with NBI may allow reliable delineation of the lateral extent of carcinomatous tissue, and in this study, a demarcation line was identified in 97 of 100 carcinomas (97%). Additionally, Nagahama et al[9] reported that magnifying endoscopy with NBI could determine margins in 72.6% of the lesions that show unclear margin using conventional endoscopes. AIM was developed by Kawahara et al[11] and they reported the diagnostic accuracy of AIM observation was 90.7%. In contrast, the diagnostic accuracy of indigo carmine observation was 75.9% in that study. AIM is also easy to use without special equipment. Kadowaki et al[12] mentioned that magnifying endoscopy with NBI and acetic acid is easier compared to other magnifying endoscopy methods to recognize the demarcation of early gastric cancers for non-expert endoscopists as well as expert endoscopists. Utilizing these advanced imaging techniques may make it easier and clearer for all endoscopists to recognize the demarcation of early gastric cancers.

Our study had a few limitations. First, we did not compare endoscopic figures with resected specimens in detail, so there was no evidence that the determination of the margin was completely correct. However, in our study, to evaluate the accuracy as precisely as possible, we strictly determined the criteria of “undelineated margin lesions” using not only endoscopic images but also pathological study of the specimens as well as was done in the study of Nagahama et al[9]. Second, our study was a retrospective study, and therefore, the individuals who performed the endoscopic resection and those who re-evaluated the lesions were not the same in almost all cases, and the margins that the 2 endoscopists considered were not same. To solve these 2 limitations, future studies could prospectively demarcate the tumor margin to be able to compare it with the endoscopically resected specimens, and the same endoscopists should evaluate the accuracy of the determination.

In conclusion, approximately 20% of differentiated early gastric cancers showed an unclear margin. Factors such as normal color, components of flat area (0-IIb), diameter ≥ 21 mm, ulceration findings, and components of poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma in the mucosal surface can make the determination of the margin difficult. During endoscopic resection, endoscopists should carefully evaluate the margin of the lesion while considering the risk factors for unclear margins.

When endoscopic resection of early gastric cancers is performed, it is important to accurately determine the margin of the lesion. A vague determination of the margin may result in residual cancer cells, which may cause recurrences and require additional resections.

Recently, imaged enhanced endoscopy (IEE) procedures, such as narrow band imaging (NBI), auto fluorescence imaging (AFI), or flexible spectral imaging color enhancement (FICE) have been developed. Especially, magnifying endoscopy with NBI may allow reliable delineation of the lateral extent of carcinomatous tissue, and it could determine margins in the lesions that show unclear margin using conventional endoscopes. However, these methods have not been adopted everywhere.

In this study, the authors evaluated the determination of the margin of differentiated-type early gastric cancers by using conventional endoscopy. In order to evaluate the accuracy as precisely as possible, the authors more strictly determined the criteria of “undelineated margin lesions” using not only endoscopic images but also pathological study of the specimens than similar studies.

The result of this study is an important benchmark to evaluate the new modalities describe above. And when these new modalities are not available, the authors should carefully evaluate the margin of the lesion while considering the risk factors for unclear margins.

Endoscopic submucosal dissection is a newly developed technique in the field of endoscopic treatment for gastrointestinal neoplasms because of its high rate of en bloc resection. IEE is a dye-based or an equipment-based image enhanced technology to increase the contrast of structures, thus making the mucosal topography, morphology and borders of lesions viewable in finer detail. NBI is one of the equipment-based image enhancement technologies, which improves the contrast of the microvascular structure and fine mucosal patterns in the mucosal surface layer using the narrow-band illumination focused two beams of 415 nm and 540 nm. AFI is one of the equipment-based image enhancement technologies based on the detection of natural tissue fluorescence emitted by endogenous molecules such as collagen, flavins, and porphyrins. FICE is one of the equipment-based image enhancement technologies, which enhance images by extracting spectral images at the desired wavelengths by applying signal processing to the white light generally used by endoscope. An acetic acid–indigo carmine mixture is one of the dye-based image enhancement technologies using both acetic acid for color contrast and indigo carmine for shape contrast.

It is a retrospective study and evaluation of various endoscopic criteria for unclear margins in early gastric cancer may not be perfect. Still this study provides useful guide for future prospective studies to define unclear margins in early gastric cancers.

P- Reviewer: Parisi A, Sharma SS S- Editor: Gong XM L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wu HL

| 1. | Gotoda T, Yanagisawa A, Sasako M, Ono H, Nakanishi Y, Shimoda T, Kato Y. Incidence of lymph node metastasis from early gastric cancer: estimation with a large number of cases at two large centers. Gastric Cancer. 2000;3:219-225. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1308] [Cited by in RCA: 1324] [Article Influence: 53.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Japanese Gastric Cancer Association. Japanese Classification of Gastric Carcinoma - 2nd English Edition. Gastric Cancer. 1998;1:10-24. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2009] [Cited by in RCA: 1942] [Article Influence: 71.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | The Paris endoscopic classification of superficial neoplastic lesions: esophagus, stomach, and colon: November 30 to December 1, 2002. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;58:S3-43. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1117] [Cited by in RCA: 1315] [Article Influence: 59.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 4. | Chonan A, Mochizuki F, Ikeda T, Lee S, Kobayashi G, Kimura K, Ando M, Watanabe H, Sato Y, Nomura M. Endoscopic determination of proximal margin in flat or depressed type gastric cancer. Gastroenterol Endosc. 1992;34:775-783. |

| 5. | Saigenji K, Ohida M, Koizumi W, Tanabe S, Imaizumi H, Mitsuhashi T, Uesugi H. Endoscopic Diagnosis of Early Gastric Cancer – Diagnosis of IIc Type Early Gastric Cancer by Conventional and Dye Endoscopy. Stomach and Intestine. 2000;35:25-36. |

| 6. | Tanabe H, Iwashita A, Haraoka S, Ikeda K, So S, Kikuchi Y, Hirai F, Yao K, Nagahama T, Takagi Y. Pathological Evaluation Concerning Curability of Endoscopic Submucosal Dissection (ESD) of Early Gastric Cancer Including Lesions with Obscure Margins. Stomach and Intestine. 2006;41:53-66. |

| 7. | Asada-Hirayama I, Kodashima S, Goto O, Yamamichi N, Ono S, Niimi K, Mochizuki S, Konno-Shimizu M, Mikami-Matsuda R, Minatsuki C. Factors predictive of inaccurate determination of horizontal extent of intestinal-type early gastric cancers during endoscopic submucosal dissection: a retrospective analysis. Dig Endosc. 2013;25:593-600. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Yao K, Anagnostopoulos GK, Ragunath K. Magnifying endoscopy for diagnosing and delineating early gastric cancer. Endoscopy. 2009;41:462-467. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Nagahama T, Yao K, Maki S, Yasaka M, Takaki Y, Matsui T, Tanabe H, Iwashita A, Ota A. Usefulness of magnifying endoscopy with narrow-band imaging for determining the horizontal extent of early gastric cancer when there is an unclear margin by chromoendoscopy (with video). Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;74:1259-1267. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 128] [Cited by in RCA: 145] [Article Influence: 10.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 10. | Osawa H, Yamamoto H, Miura Y, Yoshizawa M, Sunada K, Satoh K, Sugano K. Diagnosis of extent of early gastric cancer using flexible spectral imaging color enhancement. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;4:356-361. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Kawahara Y, Takenaka R, Okada H, Kawano S, Inoue M, Tsuzuki T, Tanioka D, Hori K, Yamamoto K. Novel chromoendoscopic method using an acetic acid-indigocarmine mixture for diagnostic accuracy in delineating the margin of early gastric cancers. Dig Endosc. 2009;21:14-19. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Kadowaki S, Tanaka K, Toyoda H, Kosaka R, Imoto I, Hamada Y, Katsurahara M, Inoue H, Aoki M, Noda T. Ease of early gastric cancer demarcation recognition: a comparison of four magnifying endoscopy methods. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;24:1625-1630. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |