Published online Jun 10, 2015. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v7.i6.593

Peer-review started: August 31, 2014

First decision: November 3, 2014

Revised: January 28, 2015

Accepted: February 9, 2015

Article in press: February 11, 2015

Published online: June 10, 2015

Processing time: 294 Days and 18.8 Hours

Achalasia is an oesophageal motor disorder which leads to the functional obstruction of the lower oesophageal sphincter (LES) and is currently incurable. The main objective of all existing therapies is to achieve a reduction in the obstruction of the distal oesophagus in order to improve oesophageal transit, relieve the symptomatology, and prevent long-term complications. The most common treatments used are pneumatic dilation (PD) and laparoscopic Heller myotomy, which involves partial fundoplication with comparable short-term success rates. The most economic non-surgical therapy is PD, with botulinum toxin injections reserved for patients with a higher surgical risk for whom the former treatment option is unsuitable. A new technology is peroral endoscopic myotomy, postulated as a possible non-invasive alternative to surgical myotomy. Other endoluminal treatments subject to research more recently include injecting ethanolamine into the LES and using a temporary self-expanding metallic stent. At present, there is not enough evidence permitting a routine recommendation of any of these three novel methods. Patients must undergo follow-up after treatment to guarantee that their symptoms are under control and to prevent complications. Most experts are in favour of some form of endoscopic follow-up, however no established guidelines exist in this respect. The prognosis for patients with achalasia is good, although a recurrence after treatment using any method requires new treatment.

Core tip: We propose a treatment and monitoring algorithm for achalasia based on the most relevant published evidence and an exhaustive summary of all the available endoscopic techniques.

- Citation: Luján-Sanchis M, Suárez-Callol P, Monzó-Gallego A, Bort-Pérez I, Plana-Campos L, Ferrer-Barceló L, Sanchis-Artero L, Llinares-Lloret M, Tuset-Ruiz JA, Sempere-Garcia-Argüelles J, Canelles-Gamir P, Medina-Chuliá E. Management of primary achalasia: The role of endoscopy. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2015; 7(6): 593-605

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v7/i6/593.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v7.i6.593

Achalasia is a primary oesophageal motor disorder of unknown aetiology characterised manometrically by insufficient relaxation of the lower oesophageal sphincter (LES) and a loss of oesophageal peristalsis[1] secondary to the degeneration of the myenteric plexus[2]. It should be suspected in patients who present with dysphagia, regurgitation of undigested food debris, respiratory symptoms, chest pain, and weight loss[3]. It is described at any age, but occurs most frequently between the ages of 20 and 40. There does not appear to be any association with sex or ethnicity. The annual incidence is 1 in 100000 persons and the prevalence is 10 in 10000[4,5]. Following clinical suspicion and diagnostic confirmation by means of a barium swallow and manometry, the indication of oesophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) in the initial phase is essential for differential diagnosis, ruling out pseudoachalasia due to malignant neoplasms and the presence of oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma as complications of achalasia. Diagnosis using high-resolution manometry and multi-channel intraluminal impedancemetry appears to have a higher diagnostic sensitivity than conventional manometry in diagnosing this disease. It also allows the identification of subtypes: Type I is associated with absent peristalsis and no discernible esophageal contractility in the context of an elevated integrated relaxation pressure (IRP). Type II is associated with abnormal esophagogastric junction (EGJ) relaxation and panesophageal pressurisation in excess of 30 mmHg. Type III achalasia is associated with premature (spastic) contractions and impaired EGJ relaxation[6].

EGD forms an essential part of the diagnostic algorithm of achalasia, although in the earliest stage it has a low sensitivity for detecting this condition as up to 40% of patients with achalasia will have a normal endoscopy[7]. The presence of oesophageal dilation on the oesophagogram, a narrowing of the oesophageal junction into a “bird beak” shape, aperistalsis, and difficulty in evacuating the barium column from the oesophagus support the diagnosis[4]. The objective of treatment is to relieve the symptoms, improve oesophageal evacuation, and prevent the development of complications. Therapeutic options include medical treatment, endoscopic treatment, including pneumatic dilation (PD) and botulinum toxin injection (BTI), and surgical LHM treatment[5]. Other treatments with a promising future which are currently being researched are POEM, oesophageal stents, and ethanolamine injection.

BTI (Botox, Allergan, Inc.) has been the most frequently used pharmacological endoscopic treatment for achalasia since 1995. Botulinum toxin is a neurotoxin which blocks the release of acetylcholine from nerve endings by cleaving the SNAP-25 protein. This causes a chemical denervation of the LES muscle, which can last several months, reducing its basal pressure[8,9]. The technique involves injecting 80 to 100 U of toxin in four quadrants (20-25 U in each) using a sclerotherapy needle, at a distance of 1 cm above the squamocolumnar junction. Higher doses have not been shown to be more efficient[10]. The initial response rate is very high, approximately 80%-90% in the month of treatment, but the therapeutic effect disappears over time such that < 50% of patients are asymptomatic after one year of monitoring[10-12]. This suggests that repeated treatments with the toxin are required every 6-12 mo. The predictive factors of a better response to treatment with BTI are: age > 40 years, achalasia type II, and a decrease in base line pressure of the LES after treatment[12]. BTI has not been shown to halt progressive oesophageal dilation, so it does not prevent long-term complications of achalasia. It is a simple, safe and effective technique with few side effects, although chest pain following injection has been described in 16%-25% of cases. Complications such as mediastinitis or allergic reactions to egg protein are rare, and systematic neurotoxicity with generalised paralysis does not occur due to the low doses used. However, repeated botulinum toxin treatments cause an intramural inflammatory reaction at the level of the LES as well as submucosal fibrosis which may make it more difficult to carry out subsequent surgical myotomy[13-15]. Treatment with BTI should therefore be reserved exclusively for patients of advanced age, those with high surgical risk, severe comorbidities, short life expectancy, and those who are not candidates for PD or surgical myotomy or on a waiting list for surgery[16].

PD is the most effective non-surgical procedure in the treatment of achalasia[4,17]. The aim of dilation treatment is to rupture the muscle fibres of the LES by means of the force exerted by air balloons positioned and inflated at this level. Both the use of bougies as well as standard balloon dilation through the endoscope channel (TTS balloon) have not been shown to be particularly effective in achieving this goal, which is necessary to significantly relieve symptoms[4]. The most commonly used dilation treatment for this disease is Rigiflex balloon dilation. Another type of balloon dilation used less frequently is the Witzel dilator, which has also been shown to be effective although it is less widely used and fewer papers have been published on it[18,19].

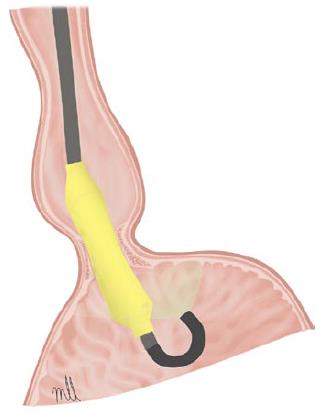

Pneumatic dilation with a Witzel balloon: Pneumatic dilation with a Witzel balloon is a relatively safe method of treating achalasia with a similar rate of complication to Rigiflex dilation, and a high level of efficacy in the medium to long term[18-20]. The Witzel dilator is a 15-cm polyurethane balloon with a maximum diameter of 4 cm, which is inserted attached to the endoscope until it is positioned at the level of the cardia using direct vision and retroflexion (Figure 1). According to the technique recommended by Alonso Aguirre[20] the balloon is inflated to 200 mmHg for 1 min and, depending on patient tolerance (if the dilation is performed under conscious sedation), it is inflated again once or twice to a maximum pressure of 200 or 300 mmHg. If the dilation is performed under deep sedation, the balloon is inflated to 200 mmHg for 2 min. In a study published for our centre in 2009[18], we observed a success rate of 85% after the first and second dilations (only required in 23% of cases). During the first 5 years of follow-up, 80% maintained the response, and the proportion decreased to around 60% after 10 years. The only variable related to a positive response in the long term was age (> 40 years). A small number of complications were reported: perforation in 4.2%, all treated conservatively, and the appearance of gastro-oesophageal reflux (GER) in the 10% who responded to treatment with proton pump inhibitors (PPI).

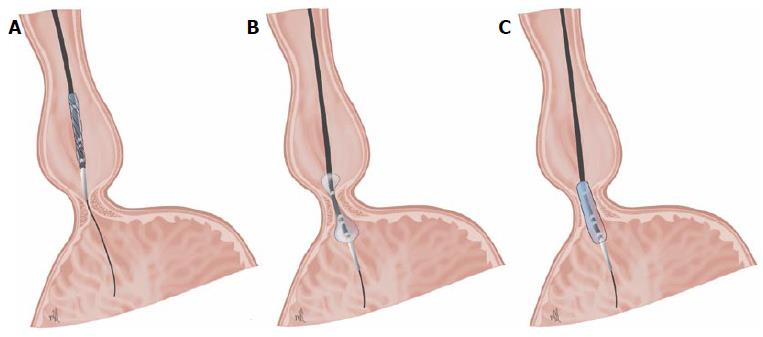

Dilation with Rigiflex balloon: The procedure has been standardised with the use of the Microinvasive Rigiflex balloon system (Boston Scientific Corp, Massachusetts, United States). These polyethylene balloons are available in 3 diameters (30, 35, and 40 mm), mounted on a flexible catheter which is positioned in the oesophagus using a guide placed with the help of an endoscope. Balloon inflation at the level of the LES can be controlled using radiology, radiopaque marking, or endoscopy (Figure 2).

The protocol for inflating the balloon varies in function from centre to centre. In general, the balloon is inflated gradually until it reaches a pressure of approximately 7-15 psi, which is maintained for 15-60 s. Using radiology, it is possible to check how the central notch on the balloon, which corresponds to the LES, disappears as the balloon is progressively inflated[21]. This is the most important factor in order for the expansion to be effective, rather than the duration of balloon inflation[22]. Following PD, some authors recommend ruling out perforation by carrying out a radiological check using Gastrografin followed by a barium oesophagogram[4,23]. This technique can usually be performed on an outpatient basis. The patient may be discharged after 6 h, once complications have been ruled out[4,21]. According to some authors, it is possible to choose whether to perform a single dilation session[24], or to carry out successive dilations, progressively increasing the diameter of the balloon in each session (beginning with 30, then 35, and finishing with 40 mm)[25], with 4-6 wk between sessions, based on alleviation of symptoms, reduction of manometric pressure in the LES[24,26], or the improvement of oesophageal evacuation[27,28]. Overall, the results of the studies published show that PD is effective, with response figures of 40%-78% at 5 years and between 12%-58% at 15 years[29-31]. By using the strategy recommended in the clinical practice guidelines[4], higher response rates of up to 97% at 5 years and 93% at 10 years can be achieved[32]. The predictive factors for a failure of treatment with PD are: young patients (age < 40 years)[18,33,34], male sex, dilation using a 30-mm balloon, presence of pulmonary symptoms, failure of treatment after one or two dilation sessions[24,29,35,36], post-treatment determination of a pressure measurement in the LES > 10-15 mmHg, failure of the balloon to relax completely[37], or delayed oesophageal evacuation in a barium oesophagogram carried out in vertical position[26,38-41]. PD is the most cost-effective treatment for achalasia for a period of 5 to 10 years after the procedures[42,43]. Candidates for PD should be those for whom surgery is not contraindicated as a definitive treatment, given that the most severe complication for this technique is oesophageal perforation, which occurs in approximately 1.9% (range 0%-16%)[28,39]. Many perforations tend to occur after the first dilation and are believed to be related to incorrect positioning and balloon relaxation during dilation[44]. Early diagnosis of this complication favours an improved course. Small perforations can be managed conservatively with parenteral nutrition and antibiotics[45], however perforations which are larger, symptomatic, or with suspected contamination of the mediastinum must be repaired surgically via thoracotomy[4,21]. Other complications include GER, which is generally mild and transient, appears in 15%-35% of patients, and usually responds to treatment with PPI[46]. Serious GER complications following dilation are rare. Mild but frequent complications include chest pain, aspiration pneumonia, bleeding, fever, tearing of the oesophageal mucosa without perforation, and oesophageal haematoma.

Botulinum toxin vs pneumatic dilation: The results of individual randomised controlled trials comparing BTI and PD have shown that there are no significant differences between the two techniques in terms of remission of symptoms in the short term (4-6 wk), but there is a rapid relapse 6-12 mo after BTI. The success rate in the year of treatment varies from 65.8%-70% for PD and 24%-36% for BTI. However, it can be concluded that PD is more effective in the long term than BTI[11,47-50].

Botulinum toxin vs laparoscopic Heller myotomy: There are few studies comparing BTI with LHM. The study by Zaninotto et al[51] reports comparable efficacy at 6 mo, although at 2 years only 34% of patients treated with BTI remain asymptomatic, as compared with 87.5% of patients treated with LHM[51].

Role of combination therapy: Therapy with BTI in combination with any other type of endoscopic or surgical treatment for achalasia can increase the response rate. Although it is still not routinely recommended in clinical practice[52], Mikaeli et al[53] published a higher remission rate during follow-up in patients who had first been treated with toxin and then with PD (77%) compared to those who had only received treatment with PD (62%)[53]. Other authors have reported a higher percentage of remission after 2 years in those who had received PD first followed by BTI (56%) compared to those who had only received dilation (35.7%), or only toxin (13.79%)[54].

Pneumatic dilation vs laparoscopic Heller myotomy: The question of whether to choose surgical treatment or PD as the primary treatment option when treating achalasia remains controversial today. Numerous studies use the strategy of repeating dilation sessions depending on the symptomatic response, if there is no improvement in the manometric tests or in the evacuation of barium contrast. This strategy enables the response rates to be increased to levels comparable with those obtained with LHM[32,55,56]. The only randomised comparative study between PD and surgery, carried out by the European Achalasia Trial Investigators Group in 2011[57] showed similar results for both techniques with a follow-up period of 2 years. 201 patients were randomised to receive dilation with Rigiflex (n = 95) or LHM with partial fundoplication (n = 106). The success rate was comparable for both techniques after 1 year and after 2 years: 90% and 86% respectively for PD, and 93% and 90% for LHM (P = 0.46). The meta-analysis published in 2009 by Campos et al[49] includes non-randomised studies of case series. They reported overall response figures of 68% in the 1065 patients dilated with Rigiflex and 89% in the 3086 patients who underwent surgery. In a study by the Cleveland Clinic (Cleveland, OH, United States)[28], 106 patients were treated with PD and 73 patients with LHM. The success rate, based on clinical data or necessity of re-treatment, was similar for both groups: 96% for dilation vs 98% for surgery after 6 mo, decreasing to 44% vs 57% after 6 years. The advantages of endoscopic treatment are that it includes the possibility of outpatient care, is less invasive than surgery, involves fewer complications and less risk of subsequent reflux and haemorrhage. However, in addition to the fact that more than one treatment session is frequently required, there are still no studies with long-term follow-up which have demonstrated the superiority of PD[21,58]. A recent meta-analysis published by Weber et al[59] found that both techniques, PD and LHM, were effective in the treatment of achalasia, however myotomy was found to be more durable[59]. There is some controversy around whether the initial PD obstructs the subsequent performance of laparoscopic myotomy[58,60]. The type of treatment must be selected consensually, taking into account the preferences of the patient as well as the experience of each centre[1,61]. These techniques should preferably be carried out by centres with a high volume and experience in LHM[58].

Peroral endoscopic myotomy: POEM is a minimally invasive procedure carried out via endoscopy. It combines the surgical principles of laparoscopic myotomy with the latest advances in endoscopic submucosal dissection[62].

The technique is performed under a general anaesthetic with endotracheal intubation and the patient in supine position. A liquid diet is indicated for 24-48 h prior to the procedure and antibiotic prophylaxis is administered on the day of the intervention, which is maintained during hospitalisation and in some cases for up to 7 d. Different authors agree on the use of CO2 insufflation to minimise the risk of pneumomediastinum and air embolism. A submucosal injection of 10 mL of saline solution with 0.3% indigo carmine is administered in the central oesophagus, about 13 cm away from to the EGJ, in a 2 o’clock position. A longitudinal incision of 2 cm is made above the surface of the mucosa to gain access to the submucosal space (Figure 3). Thus a descending anterior submucosal tunnel through the EGJ is created, which reaches approximately 3 cm into the proximal stomach. Once the submucosal tunnel is complete, the circular muscle fibres are cut 2-3 cm in distal direction from the access to the mucosa, approximately 7 cm above the EGJ. Myotomy continues distally until it reaches the gastric submucosa, and extends about 2-3 cm in distal direction to the EGJ. Once the circular muscle fibres in the lower part of the oesophagus have been identified and cut, the site of access to the mucosa is closed using haemostatic clips[63].

The first reference to endoscopic myotomy for achalasia appears in 1980 in a case series published by Ortega et al[64]. Later, as endoscopic surgery through natural orifices (NOTES) progressed, Pasricha et al[12] demonstrated its feasibility using a porcine model. The technique was adopted in clinical practice in 2010 by Inoue et al[65]. The study evaluated 17 patients, aiming for a significant reduction in the index of symptoms of dysphagia in all of them (average score from 10 to 1.3; P = 0.0003), as well as the basal pressure of the LES (from 52.4 to 19.9 mmHg; P = 0.0001). The operating time ranged from 100 to 180 min, with an average myotomy length of 8.1 cm. No serious complications related to the procedure were described. One patient presented with a complication of pneumoperitoneum. After a follow-up of 5 mo, only one patient reported symptoms of reflux, which were shown in gastroscopy to be an oesophagitis Los Angeles Grade B, which was treated satisfactorily by taking a protein pump inhibitor[65,66]. In 2011, Swanström et al[67] published their experience with POEM in 5 patients. No leaks were detected in a barium oesophagogram 24 h after the procedure, nor were any complications described immediately post-operation, with all patients presenting a rapid relief of dysphagia without reflux symptoms[66,67]. In 2012, von Renteln et al[68] presented the results of the first prospective POEM trial in Europe. The myotomy was performed in 16 patients achieving a clinical response of 94% after 3 mo. The LES pressure was reduced from 27.2 to 11.8 mmHg (P < 0.001), with no patients developing reflux symptoms after the treatment[63,68]. Some authors have studied the applicability of the techniques to patients previously subjected to endoscopic treatment (BTI, PD). Sharata et al[69] demonstrated clinical success in this context in 12 patients. Only one case of intramural bleeding, which required a new endoscopy for haemostasis, and one case of dehiscence of the mucosectomy, which was treated with haemostatic clips, were described. All patients demonstrated symptomatic relief, with an average decrease in the Eckardt score from 5 to 1. Comparing these results with those of the 28 patients without previous endoscopic treatment, no significant differences were found to exist between the two groups[66,69]. In 2012, Zhou et al[70] published their experience with 12 patients with a history of LHM in which they successfully performed endoscopic myotomy. No serious complications with the technique were described, achieving an average improvement in the index of symptoms from 9.2 to 1.3 (P < 0.001). The basal pressure of the LES was reduced from 29.4 to 13.5 mmHg (P < 0.001). Only one patient reported reflux symptoms, presenting a positive response to intermittent treatment with PPI[66,70].

The first study to retrospectively compare POEM and surgical myotomy was published in 2013. No significant differences were observed in terms of the length of the myotomy, complication rate, or hospital stay[63,71]. Bhayani et al[72] have recently presented the results of a study in which 101 patients were prospectively included, 64 treated with Heller myotomy and 37 with POEM. The authors conclude that the two techniques are comparable in terms of efficacy and safety, with similar results in post-operative manometry and pathological acid exposure, as assessed on an outpatient basis using a pH meter[72].

In summary, POEM is posited as a useful technique, although it is an expensive procedure which requires significant expertise. The studies published show excellent results in the short term as far as dysphagia relief and improvement of the manometric pressure data for the LES are concerned. The complication most frequently described is pneumoperitoneum, which can generally be resolved by conservative means. The presence of GER following POEM ranges between 5.9% and 46%, depending on the series, but in general it is a question of mild symptoms which can be adequately controlled with medical treatment. On the basis of the published data, it is no surprise that the majority of experts on POEM, including surgeons with extensive experience in surgical myotomy, appreciate the advantages of achieving results like those for LHM by minimally invasive means. Endoscopic myotomy could eventually become a first-line treatment for achalasia, except for those with significant comorbidity or advanced achalasia at the megaoesophagus stage. This technique is not a future anymore, but a present. However, new randomised studies are needed which will allow us to evaluate POEM in the long term and to compare the technique with the remaining treatment modalities.

Oesophageal prostheses: Self-expanding metallic prostheses have been used safely and effectively to treat malignant pathologies of the oesophagus and tracheoesophageal fistula, oesophageal perforations, and anastomotic leaks. However, given the high risk of complications (migration, perforation, indentation, and restenosis), its use in benign pathology is more controversial. Various authors have defended the use of removable prostheses in the management of benign stenosis of the oesophagus, arguing that it constitutes a reasonable alternative in the treatment of patients with achalasia[73,74]. The ideal prosthesis would be placed at cardia level to keep open the EGJ, thus limiting gastroesophageal reflux[75].

In 2009, Zhao et al[76] published their experience in 75 with a diagnosis of achalasia who were treated with the temporary placement of a self-expanding metallic prosthesis of 30 mm in diameter, with a follow-up of 13 years. The placement of the prosthesis is guided by a fluoroscopy and is extracted via gastroscopy 4-5 d later. The procedure was performed successfully in all patients, achieving a clinical response of 100% one month after removing the prosthesis and 83.3% in the follow-up of over 10 years. No perforations or mortalities associated with the treatment were reported, with the percentage of migration of the prosthesis at 5%, reflux at 20%, and chest pain at 38.7%. The authors conclude that the use of a temporary self-expanding metallic prosthesis is a safe and effective approach in the treatment of achalasia, with a satisfactory long-term clinical remission rate[76]. In 2010, Cheng et al[73] compared the efficacy of different self-expanding metallic prostheses in the long-term treatment of achalasia. They designed a study with 90 patients and separated them into three groups according to the diameter of the prosthesis used (20, 25, and 30 mm). They concluded that the prosthesis with a diameter of 30 mm is associated with a lower incidence of migration and with higher clinical response rates, comparable in the short term with those described for surgical myotomy[73]. The same authors published a prospective randomised study in 120 patients, in which they evaluated the long-term efficacy of a specially designed, partially covered and removable metallic prosthesis, and compared it with PD. They achieved a success rate over 10 years of 83% with the 30-mm prosthesis, while the response rate for the 20-mm prosthesis and PD was 0%[75,77].

Although the results seem promising, they reflect the experience of a single centre, which is why this technique should not be generally recommended. Further randomised studies are required which evaluate its long-term efficacy and safety[75].

Treatment of achalasia with sclerotherapy: Ethanolamine oleate: The injection of a sclerosing agent such as ethanolamine oleate at the level of the LES could be an alternative therapy for patients with refractory achalasia who are not candidates for PD or surgery. Its effect is based on the local inflammatory effect of this substance, but there are still insufficient studies and it is only to be recommended in selected cases[78,79].

Achalasia therapy is based on achieving the relaxation or mechanical disruption of the LES. Since achalasia is a rare disease, there are few randomised and controlled clinical trials which would enable us to define the optimum strategy. Furthermore, the safety and maintenance of efficacy of the different treatment options vary greatly.

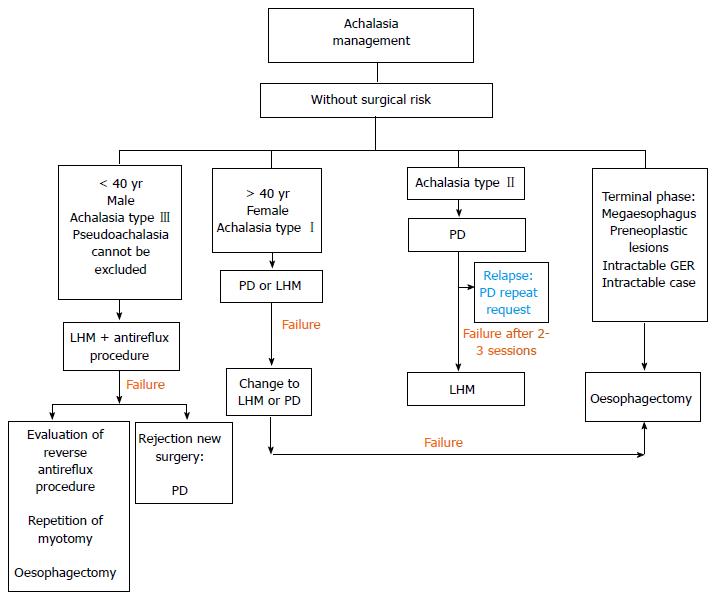

The choice of initial treatment of achalasia is complex and all options are determined by the combination of numerous factors such as the age of the patient, sex, surgical risk, comorbidity, type of achalasia[7], patient preferences, oesophageal anatomical distortion, and the experience of the hospital. Moreover, identifying factors which predict the success of the therapies can inform our recommendations. In Figures 4 and 5, we propose an algorithm for the management of this disease based on the most recent published recommendations [3-5,21,58,80,81]. In general, LHM is the most durable technique in the long term for treating achalasia, however PD is the non-surgical procedure of choice, and it is the most cost-effective strategy. Both techniques are recommended as an initial therapy for treating achalasia in healthy patients who can undergo surgery (Figure 4). The success rate in the short term is comparable for the two techniques.

PD is the most economical non-surgical option, primarily for type II. The subtype of achalasia, diagnosed using high-resolution manometry at the beginning of the study, can predict the response of the treatment[58]. Thus we have seen that the success rate with PD is significantly higher for achalasia type II (96%) than for type I (56%) and type III (29%)[82]. The sessions are repeated according to an “on demand” strategy, based on the recurrence of symptoms, and long-term remission can be achieved with it. Criteria for failure include a lack of symptom relief after 2-3 sessions or following the use of the largest diameter balloon chosen. In these cases, the patient must undergo surgery (Figure 4). In high-risk patients, PD can be a reasonable alternative if carried out in hospitals with surgical experience, because of the possibility, however infrequent, of perforation (Figure 5).

Surgical myotomy, using the technique described by Heller a century ago, is the most effective treatment option in the long term[83]. In the last 20 years, this procedure has been carried out safely and successfully using the minimally invasive laparoscopic approach[84], and more recently using robotic assistance. In the majority of cases, it is recommended to also use an anti-reflux fundoplication technique, preferably partial (Dor anterior or Toupet posterior) owing to the fact that it results in significantly lower rates of post-operative dysphagia. It is the procedure of choice in adolescents and young adults, especially male[85], in cases where pseudoachalasia cannot be ruled out and, possibly, in patients with achalasia type III (Figure 4)[82], patients with pulmonary symptoms, and those who have not responded to initial treatment with one or two sessions of dilation[37,58,86,87]. The predictors of a poor response after surgery include severe pre-operative dysphagia and preoperative low pressure of the LES (< 30-35 mmHg)[88]. The main predictor of patients who will require an additional intervention after the Heller myotomy is an oesophageal dilation of > 6 cm (megaoesophagus) in diameter prior to surgery.

Robotic surgery (Da Vinci® Surgical System, Intuitive Surgical, Mountain View, CA) has been used to treat achalasia as it meets the limitations of conventional laparoscopic surgery, making it more ergonomic for the surgeon and minimally invasive. This involves a computer-assisted surgical device with remote handling. The benefits of amplifying the three-dimensional image enable complex surgical procedures such as fundoplication LMH to be performed more accurately, helping to prevent oesophageal perforation, and to identify residual circular muscle fibres[89].

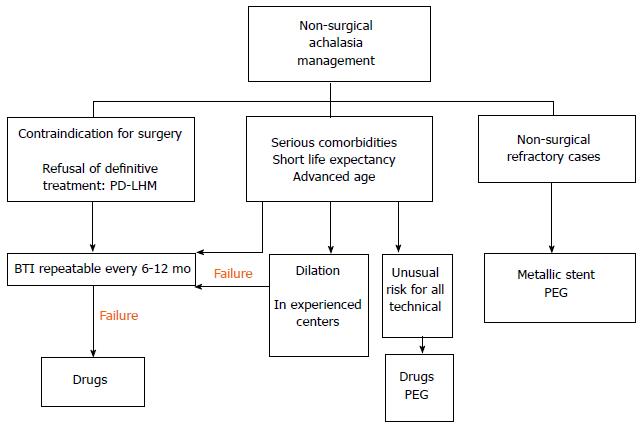

BTI is the first-line treatment for patients of advanced age, those with severe comorbidities, those with a short life expectancy[16], or those on a waiting list for surgery (Figure 5). It is recommended for patients who are not eligible for more definitive therapies (PD or LHM). Pharmacological treatment with nitrates, calcium channel blockers, and “nitric oxide donors” (sildenafil) may reduce pressure in the LES, but the efficacy is generally unsatisfactory and incomplete. It is recommended for patients who do not want or cannot undergo a more definitive treatment and for whom BTI has failed (Figure 5). Sublingual nifedipine is the most widely used drug. In a review, Cochrane, Wen et al[87], identified only two randomised studies evaluating clinical success of nitrates in achalasia and concluded that they cannot give solid recommendations for use. In our experience, it can be a treatment option prior to the extension of the myotomy or the election of oesophagectomy. BTI and medical treatment should only be used in high-risk patients (Figure 5), and as an intermediate step prior to other, more durable treatments[3].

POEM is a new treatment[90] which has shown good results in the short term, including following a myotomy with anterior fundoplication[91]. It is profiled as a viable option for patients following the failure of a myotomy, in the absence of more controlled studies, long-term results, and comparison with current techniques.

Despite the improvement in symptoms offered by PD and LHM, 10%-15% will present progressive deterioration of the oesophageal function, and up to 5% may require an oesophagectomy in the terminal stage when they do not respond to any treatment (Figure 4)[92]. The ideal method of reconstruction following oesophagectomy has not yet been established, the options being gastric, colonic, or jejunal[3]. The treatment option for refractory achalasia is (Figure 5)[93] the minimally invasive Ivor-Lewis oesophagectomy. The success rate is close to 90%, although there is a significant risk of respiratory complications, anastomotic strictures, and leaks, dumping syndrome, regurgitation, and bleeding. The placement of percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) can be considered a suitable alternative in patients with an unusually high risk for other techniques. However, it does not tend to reduce the symptoms or risks of aspiration of salivary retention.

The success of the treatment must be documented using objective parameters. Since there are deficiencies in the correlation between the latter and clinical symptoms, an adequate strategy includes periodic monitoring to detect symptomatic recurrences at an early stage. The symptoms can also reappear due to an initial incomplete myotomy, the growth of new muscular fibres, or stenosis. The first clinical evaluation should be performed at an early stage (1-3 mo) after the initial intervention, and every 1-2 years thereafter[88]. The most widely used system for scoring symptoms is the Eckardt score[94]. The Eckardt score (maximum score, 12) is the sum of the symptom scores for dysphagia, regurgitation, and chest pain (0, absent; 1, occasional; 2, daily; and 3, each meal), and weight loss (0, no weight loss; 1, < 5 kg; 2, 5-10 kg; and 3, > 10 kg). This register allows new explorations, barium oesophagram, and EGD to be indicated. In addition, regular monitoring is important not only to ensure clinical control, but also to decide on the need for retreatment and to prevent complications at a later stage. Regardless of the subtype of achalasia, the long-term positive response variable most widely used in Europe is post-treatment LES pressure < 10 mmHg[24,88,95]. Other centres use the timed measurement of the barium column after the PD as a predictor of success. In this respect, a decrease by > 50% with respect to the basal pressure within 1 min is associated with a clinical improvement[41,96]. Some institutions perform oesophageal manometry intraoperatively or immediately after the dilation[97,98]. However, the pressure of the LES could be falsely raised as a result of oedema or intramural haematoma following the intervention. There is a new method for the intraoperative evaluation of the diameter of the EGJ (EndoFLIP). It is an endoluminal probe, which produces functional images of the diameter of the EGJ in real time using impedance planimetry. However, more studies are needed to determine the best parameter for retreatment[99]. There is no treatment for the neural lesion considered to be responsible for achalasia, which is why oesophageal peristalsis is rarely normalised following any of the therapies. However, some cases have been described in which recovery of peristalsis occurs, both following myotomy and following dilation[100-104]. Different authors have associated this with close monitoring of patients and the early indication of treatment, thus avoiding progression to advanced stages with oesophageal atony.

The primary role of endoscopy is to detect, prevent, and treat immediate and long-term complications deriving from the disease itself and the therapies applied. Endoscopy immediately after an endoscopic intervention is only indicated for the treatment of complications arising from the techniques used. However, there are currently no guidelines for monitoring squamous cell carcinoma or other late complications such as oesophageal and peptic stenosis, or megaoesophagus. More data are needed to determine which follow-up guidelines will improve the overall result in this disease, since prospective monitoring studies over > 30 years have shown a benefit in long-term survival in only 13% of cases[105].

The most prevalent complications in the long term when the treatment has been effective are mainly due to GER, which occurs in almost 25% of patients after a follow-up of > 15 years[106]. Following PD, the symptoms are generally relieved and temporary, and can be easily controlled with PPI. However, more severe complications have been described following surgery, including the incidence of reflux symptoms of 18% (range 5%-55%)[49]. These complications can be markedly reduced by adding a Dor fundoplication to the LHM[107]. The second most frequent complication is the progressive dilation of the oesophagus which leads to sigmoid megaoesophagus, and appears in 10% of cases of > 10 years of progression[88]. The most feared complication is oesophageal cancer, the prevalence of which ranges from 0.4%-9.2%, squamous cell cancer being more frequent[108-111] than Barrett’s adenocarcinoma (associated with GER after myotomy). In this case, and although more studies are required, the majority of experts, including the latest guidelines from the American Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy[112], advocate some form of endoscopic surveillance 15 years after the initial diagnosis, and in patients with oesophageal stasis[5,113], but the subsequent monitoring interval has not been defined.

Achalasia is a primary oesophageal disorder for which there is no curative treatment. Pneumatic dilation and surgical myotomy are recommended initial therapies in healthy patients because they offer the best results in the long term. Botulinum toxin injection and medical treatment have transitory effects, and should be reserved for high-risk patients or as an intermediate measure before more definitive treatment. Other new options without definitive location in the therapeutic algorithm are peroral endoscopic myotomy, metallic stents, and ethanolamine injection. In refractory cases and in terminal stages, oesophagectomy is an option. Follow-up after the treatment is indicated to detect recurrences, indicate retreatment, and prevent late complications.

P- Reviewer: Kashida H, Thomopoulos KC S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor:A E- Editor: Wu HL

| 1. | O’Neill OM, Johnston BT, Coleman HG. Achalasia: a review of clinical diagnosis, epidemiology, treatment and outcomes. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:5806-5812. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 159] [Cited by in RCA: 136] [Article Influence: 11.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Clark SB, Rice TW, Tubbs RR, Richter JE, Goldblum JR. The nature of the myenteric infiltrate in achalasia: an immunohistochemical analysis. Am J Surg Pathol. 2000;24:1153-1158. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Boeckxstaens GE, Zaninotto G, Richter JE. Achalasia. Lancet. 2014;383:83-93. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 390] [Cited by in RCA: 428] [Article Influence: 38.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Vaezi MF, Pandolfino JE, Vela MF. ACG clinical guideline: diagnosis and management of achalasia. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:1238-1249; quiz 1250. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 370] [Cited by in RCA: 355] [Article Influence: 29.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Moonen AJ, Boeckxstaens GE. Management of achalasia. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2013;42:45-55. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Howard PJ, Maher L, Pryde A, Cameron EW, Heading RC. Five year prospective study of the incidence, clinical features, and diagnosis of achalasia in Edinburgh. Gut. 1992;33:1011-1015. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Pandolfino JE, Kwiatek MA, Nealis T, Bulsiewicz W, Post J, Kahrilas PJ. Achalasia: a new clinically relevant classification by high-resolution manometry. Gastroenterology. 2008;135:1526-1533. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 661] [Cited by in RCA: 551] [Article Influence: 32.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Pasricha PJ, Ravich WJ, Hendrix TR, Sostre S, Jones B, Kalloo AN. Intrasphincteric botulinum toxin for the treatment of achalasia. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:774-778. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 395] [Cited by in RCA: 331] [Article Influence: 11.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Hoogerwerf WA, Pasricha PJ. Pharmacologic therapy in treating achalasia. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2001;11:311-324, vii. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Annese V, Bassotti G, Coccia G, Dinelli M, D’Onofrio V, Gatto G, Leandro G, Repici A, Testoni PA, Andriulli A. A multicentre randomised study of intrasphincteric botulinum toxin in patients with oesophageal achalasia. GISMAD Achalasia Study Group. Gut. 2000;46:597-600. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 168] [Cited by in RCA: 134] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Vaezi MF, Richter JE, Wilcox CM, Schroeder PL, Birgisson S, Slaughter RL, Koehler RE, Baker ME. Botulinum toxin versus pneumatic dilatation in the treatment of achalasia: a randomised trial. Gut. 1999;44:231-239. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 227] [Cited by in RCA: 188] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Pasricha PJ, Rai R, Ravich WJ, Hendrix TR, Kalloo AN. Botulinum toxin for achalasia: long-term outcome and predictors of response. Gastroenterology. 1996;110:1410-1415. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 281] [Cited by in RCA: 227] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Patti MG, Feo CV, Arcerito M, De Pinto M, Tamburini A, Diener U, Gantert W, Way LW. Effects of previous treatment on results of laparoscopic Heller myotomy for achalasia. Dig Dis Sci. 1999;44:2270-2276. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Horgan S, Hudda K, Eubanks T, McAllister J, Pellegrini CA. Does botulinum toxin injection make esophagomyotomy a more difficult operation. Surg Endosc. 1999;13:576-579. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 114] [Cited by in RCA: 104] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Smith CD, Stival A, Howell DL, Swafford V. Endoscopic therapy for achalasia before Heller myotomy results in worse outcomes than heller myotomy alone. Ann Surg. 2006;243:579-584; discussion 584-586. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 181] [Cited by in RCA: 153] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Kumar AR, Schnoll-Sussman FH, Katz PO. Botulinum toxin and pneumatic dilation in the treatment of achalasia. Tec Gastrointest Endosc. 2014;16:10-19. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Vaezi MF, Richter JE. Diagnosis and management of achalasia. American College of Gastroenterology Practice Parameter Committee. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:3406-3412. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 170] [Cited by in RCA: 138] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Tuset JA, Luján M, Huguet JM, Canelles P, Medina E. Endoscopic pneumatic balloon dilation in primary achalasia: predictive factors, complications, and long-term follow-up. Dis Esophagus. 2009;22:74-79. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Ponce J, Garrigues V, Pertejo V, Sala T, Berenguer J. Individual prediction of response to pneumatic dilation in patients with achalasia. Dig Dis Sci. 1996;41:2135-2141. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Alonso-Aguirre P, Aba-Garrote C, Estévez-Prieto E, González-Conde B, Vázquez-Iglesias JL. Treatment of achalasia with the Witzel dilator: a prospective randomized study of two methods. Endoscopy. 2003;35:379-382. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Richter JE, Boeckxstaens GE. Management of achalasia: surgery or pneumatic dilation. Gut. 2011;60:869-876. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 106] [Cited by in RCA: 100] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Gideon RM, Castell DO, Yarze J. Prospective randomized comparison of pneumatic dilatation technique in patients with idiopathic achalasia. Dig Dis Sci. 1999;44:1853-1857. [PubMed] |

| 23. | Ott DJ, Richter JE, Wu WC, Chen YM, Castell DO, Gelfand DW. Radiographic evaluation of esophagus immediately after pneumatic dilatation for achalasia. Dig Dis Sci. 1987;32:962-967. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Eckardt VF, Aignherr C, Bernhard G. Predictors of outcome in patients with achalasia treated by pneumatic dilation. Gastroenterology. 1992;103:1732-1738. [PubMed] |

| 25. | Kadakia SC, Wong RK. Graded pneumatic dilation using Rigiflex achalasia dilators in patients with primary esophageal achalasia. Am J Gastroenterol. 1993;88:34-38. [PubMed] |

| 26. | Hulselmans M, Vanuytsel T, Degreef T, Sifrim D, Coosemans W, Lerut T, Tack J. Long-term outcome of pneumatic dilation in the treatment of achalasia. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;8:30-35. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 135] [Cited by in RCA: 125] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Rohof WO, Lei A, Boeckxstaens GE. Esophageal stasis on a timed barium esophagogram predicts recurrent symptoms in patients with long-standing achalasia. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:49-55. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Vela MF, Richter JE, Khandwala F, Blackstone EH, Wachsberger D, Baker ME, Rice TW. The long-term efficacy of pneumatic dilatation and Heller myotomy for the treatment of achalasia. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;4:580-587. [PubMed] |

| 29. | Eckardt VF, Gockel I, Bernhard G. Pneumatic dilation for achalasia: late results of a prospective follow up investigation. Gut. 2004;53:629-633. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 218] [Cited by in RCA: 219] [Article Influence: 10.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Katsinelos P, Kountouras J, Paroutoglou G, Beltsis A, Zavos C, Papaziogas B, Mimidis K. Long-term results of pneumatic dilation for achalasia: a 15 years’ experience. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:5701-5705. [PubMed] |

| 31. | West RL, Hirsch DP, Bartelsman JF, de Borst J, Ferwerda G, Tytgat GN, Boeckxstaens GE. Long term results of pneumatic dilation in achalasia followed for more than 5 years. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:1346-1351. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 138] [Cited by in RCA: 124] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Zerbib F, Thétiot V, Richy F, Benajah DA, Message L, Lamouliatte H. Repeated pneumatic dilations as long-term maintenance therapy for esophageal achalasia. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:692-697. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 136] [Cited by in RCA: 128] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Eckardt AJ, Eckardt VF. Current clinical approach to achalasia. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:3969-3975. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Gockel I, Junginger T, Bernhard G, Eckardt VF. Heller myotomy for failed pneumatic dilation in achalasia: how effective is it. Ann Surg. 2004;239:371-377. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Farhoomand K, Connor JT, Richter JE, Achkar E, Vaezi MF. Predictors of outcome of pneumatic dilation in achalasia. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;2:389-394. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Dağli U, Kuran S, Savaş N, Ozin Y, Alkim C, Atalay F, Sahin B. Factors predicting outcome of balloon dilatation in achalasia. Dig Dis Sci. 2009;54:1237-1242. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Alderliesten J, Conchillo JM, Leeuwenburgh I, Steyerberg EW, Kuipers EJ. Predictors for outcome of failure of balloon dilatation in patients with achalasia. Gut. 2011;60:10-16. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Vantrappen G, Hellemans J, Deloof W, Valembois P, Vandenbroucke J. Treatment of achalasia with pneumatic dilatations. Gut. 1971;12:268-275. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 146] [Cited by in RCA: 131] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Eckardt VF, Kanzler G, Westermeier T. Complications and their impact after pneumatic dilation for achalasia: prospective long-term follow-up study. Gastrointest Endosc. 1997;45:349-353. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Ghoshal UC, Kumar S, Saraswat VA, Aggarwal R, Misra A, Choudhuri G. Long-term follow-up after pneumatic dilation for achalasia cardia: factors associated with treatment failure and recurrence. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:2304-2310. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 97] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Vaezi MF, Baker ME, Achkar E, Richter JE. Timed barium oesophagram: better predictor of long term success after pneumatic dilation in achalasia than symptom assessment. Gut. 2002;50:765-770. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 211] [Cited by in RCA: 210] [Article Influence: 9.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | O’Connor JB, Singer ME, Imperiale TF, Vaezi MF, Richter JE. The cost-effectiveness of treatment strategies for achalasia. Dig Dis Sci. 2002;47:1516-1525. [PubMed] |

| 43. | Karanicolas PJ, Smith SE, Inculet RI, Malthaner RA, Reynolds RP, Goeree R, Gafni A. The cost of laparoscopic myotomy versus pneumatic dilatation for esophageal achalasia. Surg Endosc. 2007;21:1198-1206. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Metman EH, Lagasse JP, d’Alteroche L, Picon L, Scotto B, Barbieux JP. Risk factors for immediate complications after progressive pneumatic dilation for achalasia. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:1179-1185. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Vanuytsel T, Lerut T, Coosemans W, Vanbeckevoort D, Blondeau K, Boeckxstaens G, Tack J. Conservative management of esophageal perforations during pneumatic dilation for idiopathic esophageal achalasia. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;10:142-149. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Richter JE. Update on the management of achalasia: balloons, surgery and drugs. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;2:435-445. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Leyden JE, Moss AC, MacMathuna P. Endoscopic pneumatic dilation versus botulinum toxin injection in the management of primary achalasia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;CD005046. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Ghoshal UC, Chaudhuri S, Pal BB, Dhar K, Ray G, Banerjee PK. Randomized controlled trial of intrasphincteric botulinum toxin A injection versus balloon dilatation in treatment of achalasia cardia. Dis Esophagus. 2001;14:227-231. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Campos GM, Vittinghoff E, Rabl C, Takata M, Gadenstätter M, Lin F, Ciovica R. Endoscopic and surgical treatments for achalasia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Surg. 2009;249:45-57. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 481] [Cited by in RCA: 459] [Article Influence: 28.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Wang L, Li YM, Li L. Meta-analysis of randomized and controlled treatment trials for achalasia. Dig Dis Sci. 2009;54:2303-2311. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 105] [Cited by in RCA: 106] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Zaninotto G, Annese V, Costantini M, Del Genio A, Costantino M, Epifani M, Gatto G, D’onofrio V, Benini L, Contini S. Randomized controlled trial of botulinum toxin versus laparoscopic heller myotomy for esophageal achalasia. Ann Surg. 2004;239:364-370. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 205] [Cited by in RCA: 176] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Ramzan Z, Nassri AB. The role of Botulinum toxin injection in the management of achalasia. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2013;29:468-473. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Mikaeli J, Bishehsari F, Montazeri G, Mahdavinia M, Yaghoobi M, Darvish-Moghadam S, Farrokhi F, Shirani S, Estakhri A, Malekzadeh R. Injection of botulinum toxin before pneumatic dilatation in achalasia treatment: a randomized-controlled trial. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;24:983-989. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Zhu Q, Liu J, Yang C. Clinical study on combined therapy of botulinum toxin injection and small balloon dilation in patients with esophageal achalasia. Dig Surg. 2009;26:493-498. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Bravi I, Nicita MT, Duca P, Grigolon A, Cantù P, Caparello C, Penagini R. A pneumatic dilation strategy in achalasia: prospective outcome and effects on oesophageal motor function in the long term. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;31:658-665. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Allescher HD, Storr M, Seige M, Gonzales-Donoso R, Ott R, Born P, Frimberger E, Weigert N, Stier A, Kurjak M. Treatment of achalasia: botulinum toxin injection vs. pneumatic balloon dilation. A prospective study with long-term follow-Up. Endoscopy. 2001;33:1007-1017. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 110] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Boeckxstaens GE, Annese V, des Varannes SB, Chaussade S, Costantini M, Cuttitta A, Elizalde JI, Fumagalli U, Gaudric M, Rohof WO. Pneumatic dilation versus laparoscopic Heller’s myotomy for idiopathic achalasia. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1807-1816. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 698] [Cited by in RCA: 579] [Article Influence: 41.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | Chuah SK, Chiu CH, Tai WC, Lee JH, Lu HI, Changchien CS, Tseng PH, Wu KL. Current status in the treatment options for esophageal achalasia. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:5421-5429. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | Weber CE, Davis CS, Kramer HJ, Gibbs JT, Robles L, Fisichella PM. Medium and long-term outcomes after pneumatic dilation or laparoscopic Heller myotomy for achalasia: a meta-analysis. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2012;22:289-296. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 60. | Popoff AM, Myers JA, Zelhart M, Maroulis B, Mesleh M, Millikan K, Luu MB. Long-term symptom relief and patient satisfaction after Heller myotomy and Toupet fundoplication for achalasia. Am J Surg. 2012;203:339-342; discussion 342. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 61. | Spechler SJ. Pneumatic dilation and laparoscopic Heller’s myotomy equally effective for achalasia. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1868-1870. [PubMed] |

| 62. | Inoue H, Santi EG, Onimaru M, Kudo SE. Submucosal endoscopy: from ESD to POEM and beyond. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2014;24:257-264. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 63. | Allaix ME, Patti MG. New trends and concepts in diagnosis and treatment of achalasia. Cir Esp. 2013;91:352-357. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 64. | Ortega JA, Madureri V, Perez L. Endoscopic myotomy in the treatment of achalasia. Gastrointest Endosc. 1980;26:8-10. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 112] [Cited by in RCA: 101] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 65. | Inoue H, Minami H, Kobayashi Y, Sato Y, Kaga M, Suzuki M, Satodate H, Odaka N, Itoh H, Kudo S. Peroral endoscopic myotomy (POEM) for esophageal achalasia. Endoscopy. 2010;42:265-271. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1168] [Cited by in RCA: 1230] [Article Influence: 82.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 66. | Yang D, Wagh MS. Peroral endoscopic myotomy for the treatment of achalasia: an analysis. Diagn Ther Endosc. 2013;2013:389596. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 67. | Swanström LL, Rieder E, Dunst CM. A stepwise approach and early clinical experience in peroral endoscopic myotomy for the treatment of achalasia and esophageal motility disorders. J Am Coll Surg. 2011;213:751-756. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 118] [Cited by in RCA: 111] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 68. | von Renteln D, Inoue H, Minami H, Werner YB, Pace A, Kersten JF, Much CC, Schachschal G, Mann O, Keller J. Peroral endoscopic myotomy for the treatment of achalasia: a prospective single center study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:411-417. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 273] [Cited by in RCA: 250] [Article Influence: 19.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 69. | Sharata A, Kurian AA, Dunst CM, Bhayani NH, Reavis KM, Swanström LL. Peroral endoscopic myotomy (POEM) is safe and effective in the setting of prior endoscopic intervention. J Gastrointest Surg. 2013;17:1188-1192. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in RCA: 102] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 70. | Zhou PH, Li QL, Yao LQ, Xu MD, Chen WF, Cai MY, Hu JW, Li L, Zhang YQ, Zhong YS. Peroral endoscopic remyotomy for failed Heller myotomy: a prospective single-center study. Endoscopy. 2013;45:161-166. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 127] [Cited by in RCA: 136] [Article Influence: 11.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 71. | Hungness ES, Teitelbaum EN, Santos BF, Arafat FO, Pandolfino JE, Kahrilas PJ, Soper NJ. Comparison of perioperative outcomes between peroral esophageal myotomy (POEM) and laparoscopic Heller myotomy. J Gastrointest Surg. 2013;17:228-235. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 201] [Cited by in RCA: 192] [Article Influence: 16.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 72. | Bhayani NH, Kurian AA, Dunst CM, Sharata AM, Rieder E, Swanstrom LL. A comparative study on comprehensive, objective outcomes of laparoscopic Heller myotomy with per-oral endoscopic myotomy (POEM) for achalasia. Ann Surg. 2014;259:1098-1103. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 227] [Cited by in RCA: 230] [Article Influence: 20.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 73. | Cheng YS, Ma F, Li YD, Chen NW, Chen WX, Zhao JG, Wu CG. Temporary self-expanding metallic stents for achalasia: a prospective study with a long-term follow-up. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:5111-5117. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 74. | Sharma P, Kozarek R. Role of esophageal stents in benign and malignant diseases. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:258-273; quiz 274. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 253] [Cited by in RCA: 210] [Article Influence: 14.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 75. | Li YD, Cheng YS, Li MH, Chen NW, Chen WX, Zhao JG. Temporary self-expanding metallic stents and pneumatic dilation for the treatment of achalasia: a prospective study with a long-term follow-up. Dis Esophagus. 2010;23:361-367. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 76. | Zhao JG, Li YD, Cheng YS, Li MH, Chen NW, Chen WX, Shang KZ. Long-term safety and outcome of a temporary self-expanding metallic stent for achalasia: a prospective study with a 13-year single-center experience. Eur Radiol. 2009;19:1973-1980. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 77. | Pandolfino JE, Kahrilas PJ. Presentation, diagnosis, and management of achalasia. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;11:887-897. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 78. | Niknam R, Mikaeli J, Fazlollahi N, Mahmoudi L, Mehrabi N, Shirani S, Malekzadeh R. Ethanolamine oleate as a novel therapy is effective in resistant idiopathic achalasia. Dis Esophagus. 2014;27:611-616. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 79. | Moretó M, Ojembarrena E, Barturen A, Casado I. Treatment of achalasia by injection of sclerosant substances: a long-term report. Dig Dis Sci. 2013;58:788-796. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 80. | Francis DL, Katzka DA. Achalasia: update on the disease and its treatment. Gastroenterology. 2010;139:369-374. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 146] [Cited by in RCA: 154] [Article Influence: 10.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 81. | Müller M, Eckardt AJ, Wehrmann T. Endoscopic approach to achalasia. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2013;5:379-390. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 82. | Rohof WO, Salvador R, Annese V, Bruley des Varannes S, Chaussade S, Costantini M, Elizalde JI, Gaudric M, Smout AJ, Tack J. Outcomes of treatment for achalasia depend on manometric subtype. Gastroenterology. 2013;144:718-725; quiz e13-14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 356] [Cited by in RCA: 294] [Article Influence: 24.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 83. | Heller E. Extramuköse Cardiaplastik beim chronischen Cardiospasmus mit Dilatation des Oesophagus. Mitt Grenzgeb Med Chir. 1914;27:141-149. |

| 84. | Rosen MJ, Novitsky YW, Cobb WS, Kercher KW, Heniford BT. Laparoscopic Heller myotomy for achalasia in 101 patients: can successful symptomatic outcomes be predicted. Surg Innov. 2007;14:177-183. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 85. | Ghoshal UC, Rangan M. A review of factors predicting outcome of pneumatic dilation in patients with achalasia cardia. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2011;17:9-13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 86. | Chuah SK, Wu KL, Hu TH, Tai WC, Changchien CS. Endoscope-guided pneumatic dilation for treatment of esophageal achalasia. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:411-417. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 87. | Wen ZH, Gardener E, Wang YP. Nitrates for achalasia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004;CD002299. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 88. | Eckardt AJ, Eckardt VF. Treatment and surveillance strategies in achalasia: an update. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;8:311-319. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 110] [Cited by in RCA: 91] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 89. | Melvin WS, Needleman BJ, Krause KR, Wolf RK, Michler RE, Ellison EC. Computer-assisted robotic heller myotomy: initial case report. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2001;11:251-253. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 90. | Chuah SK, Hsu PI, Wu KL, Wu DC, Tai WC, Changchien CS. 2011 update on esophageal achalasia. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:1573-1578. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 91. | Vigneswaran Y, Yetasook AK, Zhao JC, Denham W, Linn JG, Ujiki MB. Peroral endoscopic myotomy (POEM): feasible as reoperation following Heller myotomy. J Gastrointest Surg. 2014;18:1071-1076. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 92. | Duranceau A, Liberman M, Martin J, Ferraro P. End-stage achalasia. Dis Esophagus. 2012;25:319-330. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 93. | Ladizinski B, Rukhman ED, Sankey C. Failure to yield: refractory achalasia. Am J Med. 2014;127:34-35. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 94. | Eckardt VF. Clinical presentations and complications of achalasia. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2001;11:281-292, vi. [PubMed] |

| 95. | Wehrmann T, Jacobi V, Jung M, Lembcke B, Caspary WF. Pneumatic dilation in achalasia with a low-compliance balloon: results of a 5-year prospective evaluation. Gastrointest Endosc. 1995;42:31-36. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 96. | Oezcelik A, Hagen JA, Halls JM, Leers JM, Abate E, Ayazi S, Zehetner J, DeMeester SR, Banki F, Lipham JC. An improved method of assessing esophageal emptying using the timed barium study following surgical myotomy for achalasia. J Gastrointest Surg. 2009;13:14-18. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 97. | Mattioli S, Ruffato A, Lugaresi M, Pilotti V, Aramini B, D’Ovidio F. Long-term results of the Heller-Dor operation with intraoperative manometry for the treatment of esophageal achalasia. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2010;140:962-969. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 98. | Endo S, Nakajima K, Nishikawa K, Takahashi T, Souma Y, Taniguchi E, Ito T, Nishida T. Laparoscopic Heller-Dor surgery for esophageal achalasia: impact of intraoperative real-time manometric feedback on postoperative outcomes. Dig Surg. 2009;26:342-348. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 99. | Familiari P, Gigante G, Marchese M, Boskoski I, Bove V, Tringali A, Perri V, Onder G, Costamagna G. EndoFLIP system for the intraoperative evaluation of peroral endoscopic myotomy. United European Gastroenterol J. 2014;2:77-83. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 100. | Zaninotto G, Costantini M, Anselmino M, Boccù C, Ancona E. Onset of oesophageal peristalsis after surgery for idiopathic achalasia. Br J Surg. 1995;82:1532-1534. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 101. | Hep A, Dolina J, Dite P, Plottová Z, Válek V, Kala Z, Prásek J. Restoration of propulsive peristalsis of the esophagus in achalasia. Hepatogastroenterology. 2000;47:1203-1204. [PubMed] |

| 102. | Lamet M, Fleshler B, Achkar E. Return of peristalsis in achalasia after pneumatic dilation. Am J Gastroenterol. 1985;80:602-604. |

| 103. | Papo M, Mearin F, Castro A, Armengol JR, Malagelada JR. Chest pain and reappearance of esophageal peristalsis in treated achalasia. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1997;32:1190-1194. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 104. | Parrilla P, Martinez de Haro LF, Ortiz A, Morales G, Garay V, Aguilar J. Factors involved in the return of peristalsis in patients with achalasia of the cardia after Heller’s myotomy. Am J Gastroenterol. 1995;90:713-717. [PubMed] |

| 105. | Leeuwenburgh I, Scholten P, Alderliesten J, Tilanus HW, Looman CW, Steijerberg EW, Kuipers EJ. Long-term esophageal cancer risk in patients with primary achalasia: a prospective study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:2144-2149. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 122] [Cited by in RCA: 109] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 106. | Leeuwenburgh I, Haringsma J, Van Dekken H, Scholten P, Siersema PD, Kuipers EJ. Long-term risk of oesophagitis, Barrett’s oesophagus and oesophageal cancer in achalasia patients. Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl. 2006;7-10. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 107. | Richards WO, Torquati A, Holzman MD, Khaitan L, Byrne D, Lutfi R, Sharp KW. Heller myotomy versus Heller myotomy with Dor fundoplication for achalasia: a prospective randomized double-blind clinical trial. Ann Surg. 2004;240:405-412; discussion 412-415. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 394] [Cited by in RCA: 362] [Article Influence: 17.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 108. | Porschen R, Molsberger G, Kühn A, Sarbia M, Borchard F. Achalasia-associated squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus: flow-cytometric and histological evaluation. Gastroenterology. 1995;108:545-549. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 109. | Streitz JM, Ellis FH, Gibb SP, Heatley GM. Achalasia and squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus: analysis of 241 patients. Ann Thorac Surg. 1995;59:1604-1609. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 101] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 110. | Chuong JJ, DuBovik S, McCallum RW. Achalasia as a risk factor for esophageal carcinoma. A reappraisal. Dig Dis Sci. 1984;29:1105-1108. [PubMed] |

| 111. | Brücher BL, Stein HJ, Bartels H, Feussner H, Siewert JR. Achalasia and esophageal cancer: incidence, prevalence, and prognosis. World J Surg. 2001;25:745-749. [PubMed] |

| 112. | Hirota WK, Zuckerman MJ, Adler DG, Davila RE, Egan J, Leighton JA, Qureshi WA, Rajan E, Fanelli R, Wheeler-Harbaugh J. ASGE guideline: the role of endoscopy in the surveillance of premalignant conditions of the upper GI tract. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;63:570-580. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 369] [Cited by in RCA: 315] [Article Influence: 16.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 113. | Dunaway PM, Wong RK. Risk and surveillance intervals for squamous cell carcinoma in achalasia. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2001;11:425-434, ix. [PubMed] |