Published online May 16, 2015. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v7.i5.547

Peer-review started: November 22, 2014

First decision: December 12, 2014

Revised: February 12, 2015

Accepted: March 5, 2015

Article in press: March 9, 2015

Published online: May 16, 2015

Processing time: 177 Days and 8.1 Hours

AIM: To investigate the results of endoscopic treatment of postoperative biliary leakage occurring after urgent cholecystectomy with a long-term follow-up.

METHODS: This is an observational database study conducted in a tertiary care center. All consecutive patients who underwent endoscopic retrograde cholangiography (ERC) for presumed postoperative biliary leakage after urgent cholecystectomy in the period between April 2008 and April 2013 were considered for this study. Patients with bile duct transection and biliary strictures were excluded. Biliary leakage was suspected in the case of bile appearance from either percutaneous drainage of abdominal collection or abdominal drain placed at the time of cholecystectomy. Procedural and main clinical characteristics of all consecutive patients with postoperative biliary leakage after urgent cholecystectomy, such as indication for cholecystectomy, etiology and type of leakage, ERC findings and post-ERC complications, were collected from our electronic database. All patients in whom the leakage was successfully treated endoscopically were followed-up after they were discharged from the hospital and the main clinical characteristics, laboratory data and common bile duct diameter were electronically recorded.

RESULTS: During a five-year period, biliary leakage was recognized in 2.2% of patients who underwent urgent cholecystectomy. The median time from cholecystectomy to ERC was 6 d (interquartile range, 4-11 d). Endoscopic interventions to manage biliary leakage included biliary stent insertion with or without biliary sphincterotomy. In 23 (77%) patients after first endoscopic treatment bile flow through existing surgical drain ceased within 11 d following biliary therapeutic endoscopy (median, 4 d; interquartile range, 2-8 d). In those patients repeat ERC was not performed and the biliary stent was removed on gastroscopy. In seven (23%) patients repeat ERC was done within one to fourth week after their first ERC, depending on the extent of the biliary leakage. In two of those patients common bile duct stone was recognized and removed. Three of those seven patients had more complicated clinical course and they were referred to surgery and were excluded from long-term follow-up. The median interval from endoscopic placement of biliary stent to demonstration of resolution of bile leakage for ERC treated patients was 32 d (interquartile range, 28-43 d). Among the patients included in the follow-up (median 30.5 mo, range 7-59 mo), four patients (14.8%) died of severe underlying comorbid illnesses.

CONCLUSION: Our results demonstrate the great efficiency of the endoscopic therapy in the treatment of the patients with biliary leakage after urgent cholecystectomy.

Core tip: Biliary leakage can be a serious complication of urgent cholecystectomy even in the hands of an experienced surgeon. Endoscopic interventions replaced surgery as first-line treatment for most of the biliary ducts injuries and biliary leakage after cholecystectomy. Long-term follow-up results demonstrate the great efficiency of the endoscopic therapy in the treatment of the patients with biliary leakage after urgent cholecystectomy. Early cessation of bile output from the external abdominal drain strongly indicates healing of the leak and in those patients repeat cholangiography is not necessary, particularly if the presenting symptoms and/or signs of the biliary leakage disappeared.

- Citation: Ljubičić N, Bišćanin A, Pavić T, Nikolić M, Budimir I, Mijić A, Đuzel A. Biliary leakage after urgent cholecystectomy: Optimization of endoscopic treatment. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2015; 7(5): 547-554

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v7/i5/547.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v7.i5.547

Biliary leakage can be a serious complication of urgent cholecystectomy even in the hands of an experienced surgeon and can lead to considerable morbidity and prolonged hospitalization. Despite the fact that there are no properly controlled trials which could identify risk factors for bile duct injury, the risk of possible perioperative complications can be estimated based on patient characteristics (commorbidity, age, gender, body weight), intraoperative findings, and the amount of training and experience of the surgeon[1-3]. Large prospective and retrospective studies have defined the risk of biliary leakage arising from either open[4-6] or laparoscopic[6-9] cholecystectomy. The number of occurrences of biliary leaks during open cholecystectomy is not precisely known, but most large series demonstrated rates of 0.5% or less[10,11]. Despite several advantages over the open approach, laparoscopy, particularly in the cases of urgent cholecystectomy, provides a limited view of the biliary tract anatomy and can result in a higher rate of biliary leaking[7]. A two to four-fold increased incidence of biliary leakage following laparoscopic cholecystectomy was demonstrated[6,9,12].

The role of endoscopic retrograde cholangiography (ERC) in the management of biliary leakage is well established. Endoscopic treatment of biliary leakage includes biliary stent insertion with or without biliary sphincterotomy, biliary sphincterotomy alone or nasobiliary tube placement. All those methods have been demonstrated to be effective treatment for biliary leakage without need for further surgery[13-15]. However, the need for an endoscopic sphincterotomy, the choice between nasobiliary tube drainage and endoscopic biliary stenting and the preferable type of stent (short or long stent; larger or smaller diameter) are still the matter of extensive debate. Therefore, optimal endoscopic intervention is still not established and data regarding the long-term follow-up of those patients is missing.

The aim of this study was to determine the results of endoscopic treatment of postoperative biliary leakage occurring after urgent cholecystectomy with a long-term follow-up.

This is an observational database study conducted in a tertiary care center with primary uptake area covering a population of approximately 300000 people (City of Zagreb, Republic of Croatia). The study was approved by the “Sestre milosrdnice” University Hospital Review Board. All consecutive patients who underwent ERC for presumed postoperative biliary leakage following urgent cholecystectomy between April 2008 and April 2013 were considered for this study. All the patients included in the study signed the informed consent statement. Patients with bile duct transection and biliary strictures were excluded. Biliary leakage was suspected in case of bile appearance from either percutaneous drainage of abdominal collection or abdominal drain placed at the time of cholecystectomy.

Information of all consecutive patients with postoperative biliary leakage, including cholecystectomy details such as indication for cholecystectomy, etiology and type of leakage, ERC findings and post-ERC complications, were reviewed from our electronic database. The grading of overall health and comorbidity was performed according to the American Society of Anesthesiology classification[16]. All ERC successfully treated patients were followed-up after they were discharged from the hospital and the main clinical characteristics and laboratory data, including levels of bilirubin, alanine transaminase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase, GGT, alkaline phosphatase, CRP and common bile duct diameter measured on transabdominal ultrasound were electronically recorded every month during first 6 mo, then every 6 mo.

ERC was performed with standard equipment (TJF 145, Olympus Optical Co., Japan), and by the well-trained endoscopists, each with at least five-year experience. Selective cannulation of the common bile duct was attempted with a standard wire-guided sphincterotome and 0.035-inch hydrophilic guidewire. If the efforts to enter the common bile duct were unsuccessful, a needle-knife papillotomy was performed. In all patients ERC was performed under intravenous sedation and analgesia (propofol and fentanyl) under direct anesthesiologist control. Pre-procedural antibiotics were administered (ciprofloxacin 400 mg iv).

Post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) pancreatitis was identified by characteristic abdominal pain associated with serum amylase levels at least three times the upper limits of normal. Postprocedural bleeding was defined as one or more signs of ongoing bleeding, including fresh hematemesis or melena, hematochezia, aspiration of fresh blood via nasogastric tube, vital signs instability, and a reduction of hemoglobin level by more than 2 g/dL over a 24-h period.

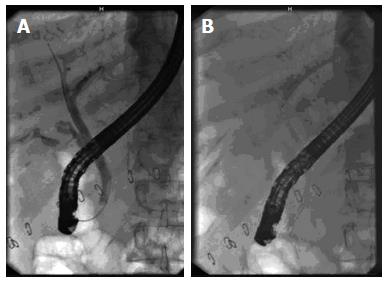

In all patients with a cholangiographic evidence of a biliary leakage the placement of a plastic 10 F biliary stent without biliary sphincterotomy was performed. The standard procedure was to place proximal end of a biliary stent above the level of the leak in patients with the cholangiographic evidence of a leakage from the common bile duct or from cystic duct stump or cholecystohepatic duct of Luschka (Figure 1). If biliary leakage from the right hepatic duct or intrahepatic duct was confirmed, and in patients in whom biliary leakage was not located, only short plastic 10F biliary stent was inserted. In patients with a cholangiographic evidence of a biliary leakage and a common bile duct stone(s), biliary sphincterotomy was performed and after the stone was removed (with balloon catheter or Dormia basket), plastic 10F biliary stent was placed.

The clinical healing of the biliary leakage was determined by the complete absence of the symptoms, cessation of the output of the bile from the drain and by the removal of the drain without any further adverse outcomes. The failure of the endoscopic treatment was determined by the need for further intervention to control the leak including surgery and/or percutaneous drainage of the biliary tree.

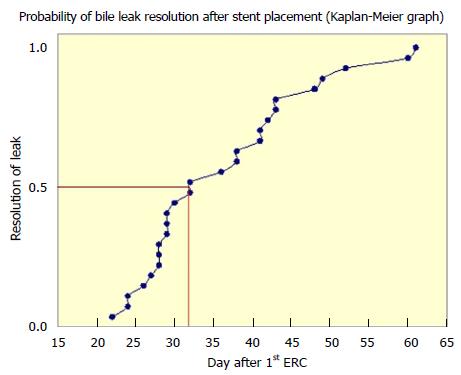

All analysis were performed by an expert biomedical statistician with a statistical package (Statistica 10.0 for Windows, United States). Descriptive statistics were used in this case series to describe characteristics of the patients, procedures and outcomes. Continuous variables are expressed as medians with interquartile ranges for nonparametric values. Median time to biliary leakage closure and median time were estimated using a Kaplan-Meier survival curve. Spearman correlation coefficients were calculated to assess interrelationships of certain quantitative variables. A P values below 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

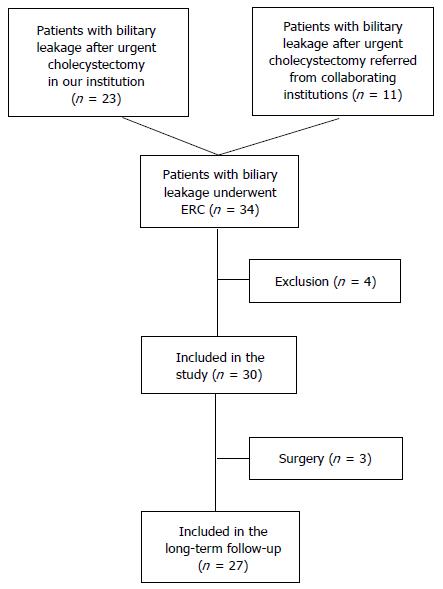

Among 2472 ERCP procedures that were performed in our center between April 2008 and April 2013, there were 34 patients who underwent ERC because of postoperative biliary leakage occurring after urgent cholecystectomy: 23 patients in whom urgent cholecystectomy was performed at our institution and 11 patients referred from our collaborating institutions (Figure 2). In the same period urgent cholecystectomy was performed in 1058 patients (31 patients with gallstones and hydrops of the gallbladder, 662 patients with acute or subacute calculous cholecystitis, 365 patients with gangrenous cholecystitis and one patient with Mirizzi’s syndrome) at our institution. Since endoscopic treatment is a standard practice for management of post-cholecystectomy biliary leakage at our hospital, all the patients with suspected biliary leakage were referred to the endoscopy unit. Therefore, during a 5-year period biliary leakage occurred in 2.2% of all patients who underwent urgent cholecystectomy. In all those patients indications for urgent cholecystectomy were acute or subacute calculous cholecystitis (21 patients) or gangrenous cholecystitis (13 patients).

Initial ERC was successful in 32 out of 34 patients (94%). The reasons for failure of ERC in two patients were intradiverticular location of the papilla seen in one patient and the presence of a Billroth II operation in a second patient. Patient with intradiverticular location of the papilla was successfully treated with the rendezvous technique[12] and this patient was included in the study. In two patients in whom ERC was successfully performed, the cholangiography demonstrated a complete transection of the common bile duct (first patients) and significant common bile duct stenosis because of multiple clips across the bile duct (second patient). Surgery was recommended for those patients as well as for the patient with the presence of a Billroth II operation. Those three patients were excluded from the study. One patient, at the age of 79, with severe comorbidities, including heart failure with permanent atrial fibrillation, arterial hypertension, diabetes and renal insufficiency, died immediately after ERC (with stent in place) because of acute myocardial infarction and cardiac arrest. This patient was also excluded from the study.

The main clinical characteristics of 30 consecutive patients with postoperative biliary leakage included in the study are summarized in Table 1.

| Parameter | n (%) |

| Age (yr) (median) | 62 |

| Male/female | 14 (46.7)/16 (53.3) |

| Cholecystectomy details | |

| Open | 9 (30.0) |

| Laparoscopic | 13 (43.3) |

| Laparoscopic to open conversion | 8 (26.7) |

| Abdominal drain: | |

| Bile leak ≤ 400 mL/d | 24 (80.0) |

| Bile leak > 400 mL/d | 6 (20.0) |

| Abdominal pain | 20 (66.7) |

| Jaundice | 8 (26.7) |

| Fever | 14 (46.7) |

| Abdominal collection | 8 (26.7) |

| Abdominal distension | 6 (20.0) |

| Ascites | 1 (3.3) |

| Comorbidity | |

| ASA 1-2 | 24 (80.0) |

| ASA 3-4 | 6 (20.0) |

The median time from cholecystectomy to ERC was 6 d (interquartile range, 4-11 d) and 4 (13%) patients underwent ERC more than 2 wk after surgery. Most common biliary leakage sites included leak from the cystic duct stump in 13 patients, the right hepatic duct or intrahepatic duct in 12 patients, leak from the common bile duct in three patients and from cholecystohepatic duct of Luschka in one patient (Table 2).

| 1st ERC findings | n (%) |

| Number of patients | 30 |

| Bile leak characteristics | |

| Leak from the cystic duct stump | 13 (43.3 |

| Leak from the right hepatic duct or intrahepatic duct | 12 (40.0) |

| Leak from the common bile duct | 3 (10.0) |

| Leak from cholecystohepatic duct of Luschka | 1 (3.3) |

| Could not be located | 1 (3.3) |

| CBD stone(s) | 11 (36.7) |

| Endoscopic management | |

| Biliary stent | 13 (43.3) |

| EBS + stone extraction + biliary stent | 11 (36.7) |

| EBS + biliary stent | 6 (20.0) |

| Adverse effect | |

| Pancreatitis | 2 (6.7) |

| Bleeding | 1 (3.3) |

| 1st ERC leakage resolution success rate | 23/30 (76.7) |

| Repeated ERC findings | |

| Number of patients | 7 |

| Bile leak characteristics | |

| Leak from the right hepatic duct or intrahepatic duct | 6 (85.7) |

| Could not be located | 1 (14.3) |

| CBD stone(s) | 2 (28.6) |

| Endoscopic management | |

| Biliary stent | 5 (71.4) |

| EBS + extraction + biliary stent | 2 (28.6) |

| Adverse effect | 0 |

| ERC leakage resolution success rate | 27/30 (90) |

| Referred to surgery | 3 (10) |

Endoscopic biliary sphincterotomy was performed in 17 patients: 11 patients with cholangiographic evidence of common bile duct stone(s), 3 patients with suspected but not proven common bile duct stone, and three patients in whom cannulation of the common bile duct was difficult (in two of them needle-knife papillotomy was performed). All those patients underwent plastic 10 F biliary stent placement. The proximal end of the biliary stent was placed above the site of the biliary leakage in 16 patients with leakage from the cystic duct stump, cholecystohepatic duct of Luschka and leakage from the common bile duct (based on the endoscopist’s discretion, only in one patient biliary stent was placed below the site of the biliary leakage). In patients with biliary leakage from the right hepatic duct or intrahepatic duct and in patients in whom biliary leakage was not located on cholangiography, only short plastic 10 F biliary stent stranding the papilla was inserted.

After first endoscopic treatment bile flow through existing surgical drain ceased in 23 (77%) patients within 11 d following biliary therapeutic endoscopy (median, 4 d; interquartile range, 2-8 d). Those patients become asymptomatic with the normalization in laboratory data, and the biliary stent was removed on gastroscopy.

Mild post-ERC pancreatitis was observed in two patients after needle-knife papillotomy was performed. The occurrence of ERC-related pancreatitis did not affect the ultimate outcome in any of them. Post-ERC bleeding was observed in only one patient with liver cirrhosis and heart failure in which biliary sphincterotomy was performed (reduction of hemoglobin level by more than 2g/dL over a 24-h period). This patient was successfully treated conservatively and the occurrence of post-ERC bleeding did not affect the ultimate outcome of this patient. Duodenal perforation was not observed (Table 2).

In seven (23%) patients in whom persistent bile flow through existing surgical drain was demonstrated, suggesting the absence of the biliary leakage resolution, repeat ERC was performed within one to 4 wk, depending on the extent of the biliary leakage. In all those patients biliary stent was removed and replaced with a new one (Table 2). In two patients common bile duct stone was recognized and removed with a balloon catheter. After the repeat ERC was performed, four of those seven patients had cessation of bile flow through existing surgical drain within two to nine days (median, 5.5 d). Those four patients become asymptomatic with the normalization in laboratory data, and the biliary stent was removed on gastroscopy. There were no adverse events related to the repeat ERC.

Overall, 27 (90%) patients with biliary leakage after urgent cholecystectomy included in study were successfully treated with ERC, and all those patients were included in the long-term follow-up. ERC was repeated in 14.8% of patients, and 1.1 ERC procedure was needed for every patient with leakage resolution.

Three patients (10%) with biliary leakage after urgent cholecystectomy included in the study had more complicated clinical course. One of them had a continuous biliary leakage demonstrated as the high-output bile flow through existing surgical drain. In this patient second repeat ERC revealed large right hepatic duct biliary leakage. This patient was referred to surgery together with two patients in whom large symptomatic subphrenic abscess was confirmed along with a persistent biliary leakage through the surgical drain. Altogether eight patients had the abdominal fluid collection, and six were treated conservatively.

In all patients in whom endoscopic therapy led to the complete resolution of biliary leakage, median interval from the first endoscopic intervention and biliary stent placement to the stent extraction was 32 d (interquartile range, 28-43 d) (Figure 3). Median interval from the therapeutic ERC (first or repeated) to the stent extraction was 32 d, also (interquartile range, 28-42 d). Cessation of the bile flow through existing surgical drain occurred up to eleventh day after therapeutic ERC (first or repeated; median, 4 d, interquartile range, 2-8 d). There was no correlation between the volume of bile leak output on a surgical drain and the probability of bile leakage resolution after ERC (r = 0.161, P = 0.537).

Among 27 patients initially included in the long-term follow-up (median 30.5 mo, range 7-59 mo), four patients (14.8%) died. All of deceased patients died of severe underlying comorbid illnesses: malignancy (one patient), cerebrovascular accidents (one patient), heart failure (two patients). The main clinical characteristics and laboratory data of patients included in the long-term follow-up are demonstrated in Table 3. All those patients were asymptomatic with normal levels of bilirubin and without any signs of cholangitis and bile duct dilation. In 13 (48.2%) patients increase in ALT concentration (up to two times above the normal values) was observed. In all those patients endoscopic ultrasound revealed normal finding of common bile duct.

| Parameter | n (%) |

| Number of patients | 27 |

| Abdominal pain | 0 |

| Abdominal distension | 0 |

| Elevated bilirubin¹ | 0 |

| Elevated ALT² | 13 (48.2) |

| Dilated common bile duct (> 6 mm)³ | 0 |

| Death | 4 (14.8) |

Postoperative biliary leakage is a serious complication that occurs in 0.2%-2.2% of all cholecystectomies[4-7,17], and even more frequently after laparoscopic cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis[9]. In accordance with the results of our study, during 5-year period biliary leakage occurred in 2.2% of patients who underwent urgent cholecystectomy. This percentage is high with regard to the percentage of biliary leakage among patients who underwent either open or laparoscopic cholecystectomy that had been reported previously. It is possible to assume that mechanisms responsible for those findings in patients after urgent cholecystectomy include the presence of inflammation and edema (the cystic duct is indurated and shortened, lying in close contact with the common bile duct), or bleeding[6,9]. That may lead to the poor identification of anatomical structures including possible aberrant anatomy and dislodgement of suboptimally placed clips or a bile duct injury, where the experience of the surgeon is crucial[1,6,9,13].

Endoscopic interventions replaced surgery as first-line treatment for most of the biliary ducts injuries and biliary leakage following cholecystectomy. All of them are aimed towards decreasing the transpapillary pressure, allowing bile to flow through the path of decreased resistance. As a consequence, biliary leakage closes spontaneously. Recent data strongly suggest that biliary stent placement without biliary sphincterotomy is more efficient and has a lower complication rate than biliary sphincterotomy[18,19]. Since endoscopic treatment is a standard practice for management of postcholecystectomy biliary leakage at our institution, all the patients with suspected biliary leakage were referred to the endoscopy unit. Therefore, only patients with biliary leakage after urgent cholecystectomy were included in our study. To our knowledge this is the first long-term follow-up study investigating the efficiency of the endoscopic therapy in patients with biliary leakage occurring after urgent cholecystectomy. Our results clearly demonstrated the great efficiency of the endoscopic therapy in the treatment of the patients with biliary leakage. Among our group of patients closure of bile leaks was achieved with endoscopic therapy in great majority of patients (90%).

There are several limitations to this study. First, the number of patients was relatively small, although the study period included five years, but the protocol narrowed the inclusion criteria. Second, our management algorithm did not include some other available imaging methods like magnetic retrograde cholangiography because technical success of the initial ERC was rather high (94%) and this could be regarded as redundant.

There are no uniform recommendations regarding the need for repeat cholangiography at the time when previously positioned biliary stent need to be removed after resolution of biliary leakage. Namely, when endoscopic biliary stents are placed, the precise time when the leak closes cannot be determined. To our results, early cessation of bile output from the external abdominal drain strongly indicates healing of the bile leak. In majority of those patients presenting clinical symptoms and/or signs disappear very fast. Contrary, the persistent bile flow through existing surgical drain, in our study more than 11 d after endoscopic stent placement, indicates the persistent biliary leakage. In those patients, repeat ERC or some other procedure seems to be necessary. Reason for the persistent biliary leakage, as we found in our study, might be the presence of a previously unrecognized common bile duct stones, inadequately drained abdominal collection with inflammation and abscess formation or magnitude of bile duct defect.

Despite the fact that there are no uniform recommendations regarding the need for cholangiography at the time of stent removal, few studies demonstrated that repeat cholangiography is not necessary in patients in whom the presenting symptoms and/or signs of the biliary leakage had been disappeared. In those clinically well patients gastroscopy with biliary stent removal is effective if performed after the median time of 33 d following biliary stent placement[20-22]. In our study we clearly demonstrated that in asymptomatic patients following urgent cholecistectomy in whom early cessation of bile output from the external abdominal drain occurred (median, 4 d, interquartile range, 2-8 d), biliary stent removal on gastroscopy is safe after the median time of 32 d after biliary stent placement without any need for repeat cholangiography.

During hospitalization, only one 79 years old patient with severe comorbidities, including heart failure with permanent atrial fibrillation, arterial hypertension, diabetes and renal insufficiency, died immediately after ERC (with stent in place) because of acute myocardial infarction and cardiac arrest. Among 27 patients included in the long-term follow-up four of them died. The main contributory factor that considerably affects patient’s prognosis seems to be the comorbidity. Namely, among deceased patients all of them died of severe underlying comorbid illnesses, unrelated with cholecystectomy or endoscopic procedure.

In conclusion, despite the fact that the major limitation of our study is relatively small number of patients, long-term follow-up results demonstrate the great efficiency of the endoscopic therapy in the treatment of the patients with biliary leakage following urgent cholecystectomy. Early cessation of bile output from the external abdominal drain strongly indicates healing of the leak and in those patients repeat cholangiography is not necessary, particularly if the presenting symptoms and/or signs of the biliary leakage disappeared.

Biliary leakage can be a serious complication of urgent cholecystectomy even in the hands of an experienced surgeon. Endoscopic interventions replaced surgery as first-line treatment for most of the biliary ducts injuries and biliary leakage. Long-term follow-up results in this study demonstrate the great efficiency of the endoscopic therapy in the treatment of the patients with biliary leakage after urgent cholecystectomy.

This paper describes a novel approach to endoscopic retrograde cholangiography procedure as a treatment for resolution of biliary leakage following urgent cholecystectomy.

This paper for the first time demonstrates the great efficiency of the endoscopic therapy in the treatment of the patients with biliary leakage after urgent cholecystectomy. Early cessation of bile output from the external abdominal drain strongly indicates healing of the leak and in those patients repeat cholangiography is not necessary.

Considering the tendency of early cholecystectomy in acute cholecystitis, and an increase in the number of laparoscopic procedures in the future, it is possible to expect a lot of patients with biliary leakage, especially after the urgent cholecystectomy. These results could be also applied to all patients with biliary leakage.

This is an interesting and practical paper about biliary leakage after surgery for acute cholecystitis. The subject is of paramount importance because most of the series mixed leakage after planned and emergency cholecystectomies.

P- Reviewer: Hussain A, Lee CL, Regimbeau JM S- Editor: Gong XM L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wu HL

| 1. | Strasberg SM, Hertl M, Soper NJ. An analysis of the problem of biliary injury during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. J Am Coll Surg. 1995;180:101-125. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Brugge WR, Rosenberg DJ, Alavi A. Diagnosis of postoperative bile leaks. Am J Gastroenterol. 1994;89:2178-2183. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Giger UF, Michel JM, Opitz I, Th Inderbitzin D, Kocher T, Krähenbühl L. Risk factors for perioperative complications in patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy: analysis of 22,953 consecutive cases from the Swiss Association of Laparoscopic and Thoracoscopic Surgery database. J Am Coll Surg. 2006;203:723-728. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 213] [Cited by in RCA: 230] [Article Influence: 12.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Hillis TM, Westbrook KC, Caldwell FT, Read RC. Surgical injury of the common bile duct. Am J Surg. 1977;134:712-716. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Andrén-Sandberg A, Johansson S, Bengmark S. Accidental lesions of the common bile duct at cholecystectomy. II. Results of treatment. Ann Surg. 1985;201:452-455. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 137] [Cited by in RCA: 145] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Kiviluoto T, Sirén J, Luukkonen P, Kivilaakso E. Randomised trial of laparoscopic versus open cholecystectomy for acute and gangrenous cholecystitis. Lancet. 1998;351:321-325. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 290] [Cited by in RCA: 254] [Article Influence: 9.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Pesce A, Portale TR, Minutolo V, Scilletta R, Li Destri G, Puleo S. Bile duct injury during laparoscopic cholecystectomy without intraoperative cholangiography: a retrospective study on 1,100 selected patients. Dig Surg. 2012;29:310-314. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Voyles CR, Sanders DL, Hogan R. Common bile duct evaluation in the era of laparoscopic cholecystectomy. 1050 cases later. Ann Surg. 1994;219:744-750; discussion 750-752. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Brodsky A, Matter I, Sabo E, Cohen A, Abrahamson J, Eldar S. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis: can the need for conversion and the probability of complications be predicted? A prospective study. Surg Endosc. 2000;14:755-760. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Bernard HR, Hartman TW. Complications after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Am J Surg. 1993;165:533-535. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Clavien PA, Sanabria JR, Mentha G, Borst F, Buhler L, Roche B, Cywes R, Tibshirani R, Rohner A, Strasberg SM. Recent results of elective open cholecystectomy in a North American and a European center. Comparison of complications and risk factors. Ann Surg. 1992;216:618-626. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 88] [Cited by in RCA: 119] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Barkun AN, Rezieg M, Mehta SN, Pavone E, Landry S, Barkun JS, Fried GM, Bret P, Cohen A. Postcholecystectomy biliary leaks in the laparoscopic era: risk factors, presentation, and management. McGill Gallstone Treatment Group. Gastrointest Endosc. 1997;45:277-282. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 110] [Cited by in RCA: 101] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Mehta SN, Pavone E, Barkun JS, Cortas GA, Barkun AN. A review of the management of post-cholecystectomy biliary leaks during the laparoscopic era. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997;92:1262-1267. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Carr-Locke AD. ‘Biliary stenting alone versus biliary stenting plus sphincterotomy for the treatment of post-laparoscopic cholecystectomy bile leaks’. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;18:1053-1055. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Pinkas H, Brady PG. Biliary leaks after laparoscopic cholecystectomy: time to stent or time to drain. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2008;7:628-632. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Keats AS. The ASA classification of physical status--a recapitulation. Anesthesiology. 1978;49:233-236. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 523] [Cited by in RCA: 513] [Article Influence: 10.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Vecchio R, MacFadyen BV, Latteri S. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy: an analysis on 114,005 cases of United States series. Int Surg. 1998;83:215-219. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Mavrogiannis C, Liatsos C, Papanikolaou IS, Karagiannis S, Galanis P, Romanos A. Biliary stenting alone versus biliary stenting plus sphincterotomy for the treatment of post-laparoscopic cholecystectomy biliary leaks: a prospective randomized study. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;18:405-409. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Pioche M, Ponchon T. Management of bile duct leaks. J Visc Surg. 2013;150:S33-S38. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Ahmad F, Saunders RN, Lloyd GM, Lloyd DM, Robertson GS. An algorithm for the management of bile leak following laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2007;89:51-56. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Coelho-Prabhu N, Baron TH. Assessment of need for repeat ERCP during biliary stent removal after clinical resolution of postcholecystectomy bile leak. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:100-105. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Sachdev A, Kashyap JR, D’Cruz S, Kohli DR, Singh R, Singh K. Safety and efficacy of therapeutic endoscopic interventions in the management of biliary leak. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2012;31:253-257. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |