Published online Apr 16, 2015. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v7.i4.403

Peer-review started: October 1, 2014

First decision: October 28, 2014

Revised: November 27, 2014

Accepted: January 18, 2015

Article in press: January 20, 2015

Published online: April 16, 2015

Processing time: 200 Days and 14.8 Hours

AIM: To investigate long-term re-bleeding events after a negative capsule endoscopy in patients with obscure gastrointestinal bleeding (OGIB) and the risk factors associated with the procedure.

METHODS: Patients referred to Hospital Egas Moniz (Lisboa, Portugal) between January 2006 and October 2012 with OGIB and a negative capsule endoscopy were retrospectively analyzed. The following study variables were included: demographic data, comorbidities, bleeding-related drug use, hemoglobin level, indication for capsule endoscopy, post procedure details, work-up and follow-up. Re-bleeding rates and associated factors were assessed using a Cox proportional hazard analysis. The Kaplan-Meier method was used to estimate the cumulative incidence of re-bleeding at 1, 3 and 5 years, and the differences between factors were evaluated.

RESULTS: The study population consisted of 640 patients referred for OGIB investigation. Wireless capsule endoscopy was deemed negative in 113 patients (17.7%). A total of 64.6% of the population was female, and the median age was 69 years. The median follow-up was forty-eight months (interquartile range 24-60). Re-bleeding occurred in 27.4% of the cases. The median time to re-bleeding was fifteen months (interquartile range 2-33). In 22.6% (n = 7) of the population, small-bowel angiodysplasia was identified as the culprit lesion. A univariate analysis showed that age > 65 years old, chronic kidney disease, aortic stenosis, anticoagulant use and overt OGIB were risk factors for re-bleeding; however, on a multivariate analysis, there were no risk factors for re-bleeding. The cumulative risk of re-bleeding at 1, 3 and 5 years of follow-up was 12.9%, 25.6% and 31.5%, respectively. Patients who presented with overt OGIB tended to re-bleed sooner (median time for re-bleeding: 8.5 mo vs 22 mo).

CONCLUSION: Patients with OGIB despite a negative capsule endoscopy have a significant re-bleeding risk; therefore, these patients require an extended follow-up strategy.

Core tip: This study describes a large cohort of patients with obscure gastrointestinal bleeding in whom the first capsule endoscopy was negative. Re-bleeding events, risk factors and causes were analyzed. A significant risk of re-bleeding was observed; however, independent predictors for re-bleeding were not identified. Re-bleeding due to small-bowel angiodysplasia was a frequent occurrence; therefore, these patients require an extended follow-up strategy, perhaps involving repeated endoscopic procedures if re-bleeding occurs.

- Citation: Magalhães-Costa P, Bispo M, Santos S, Couto G, Matos L, Chagas C. Re-bleeding events in patients with obscure gastrointestinal bleeding after negative capsule endoscopy. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2015; 7(4): 403-410

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v7/i4/403.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v7.i4.403

Obscure gastrointestinal bleeding (OGIB) represents approximately 5% of all gastrointestinal bleeding cases and, in most cases, the culprit lesion located in the small-bowel[1]. OGIB is defined as bleeding from the gastrointestinal tract that persists or recurs without an obvious source, as assessed by esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD), colonoscopy and radiologic evaluation of the small-bowel[1]. OGIB is classified as either occult or overt; occult OGIB is characterized by iron deficiency anemia (IDA) with or without a positive fecal occult blood test[1,2], and overt OGIB is characterized by clinically perceptible bleeding that recurs or persists despite negative initial endoscopic (EGD and colonoscopy) and radiologic evaluations. Wireless capsule endoscopy (WCE) is a cost-effective investigation in patients with OGIB[3]. In one study, after a WCE evaluation, there was a significant reduction in hospitalizations, additional investigations and units of blood transfused compared to before WCE[4]. Currently, OGIB is the main indication for a capsule endoscopy study. A myriad of studies have analyzed and compared the diagnostic yield (vs other techniques)[5-7] and clinical impact of a positive WCE study on patient outcome[8]. Still, a negative WCE study remains a clinical challenge, and little is known about the long-term follow-up of such patients. Therefore, many questions persist about the “protective effect” of a negative WCE study on future re-bleeding events. To date, there are some conflicting data about the re-bleeding rates and predictive factors linked to a re-bleeding event, and in addition, the median follow-up period varies substantially among studies[9-15]. The aim of this study is to assess the long-term outcome (especially re-bleeding events) after a negative WCE study in patients referred for OGIB investigation and risk factors associated with a re-bleeding event.

We present a retrospective, observational cohort, single center study. Clinical data were obtained from medical records of all patients referred to our tertiary referral hospital - Endoscopy Unit (Hospital Egas Moniz, Centro Hospitalar Lisboa Ocidental, Lisboa) - to undergo a WCE for OGIB investigation between January 2006 and October 2012. All of the patients presented with overt or occult gastrointestinal bleeding according to guidelines[1]. All patients had at least one negative EGD and ileo-colonoscopy before referral for WCE. After signing a written informed consent, every patient underwent a WCE with a PillCam SB (R) (M2A, from January 2006) or SB2©(since June 2007) capsule endoscopy system (Given Imaging, Yoqneam, Israel) according to the standard protocols[16]. All the procedures were performed in an outpatient setting. Since January 2008, a small-bowel purgative preparation with a 2-L polyethylene glycol solution before WCE was introduced in our protocol. Simethicone was also used on a routine basis before all procedures. Two hours after taking the capsule, patients received a clear liquid diet and, two hours later, a light meal, as recommended in the standard protocol. Eight hours after WCE, the patients returned to the Endoscopy Unit, the data recorder was removed, and images were downloaded. The recordings were independently reviewed by four experienced gastroenterologists (Chagas C, Couto G, Santos S, Bispo M) at 8-10 frames per second using the Rapid® Reader. When possible, the colon was also observed. The WCE findings were classified into three types based on the Saurin classification[17,18] as follows: lesions considered to have a high potential for bleeding (P2); lesions with uncertain bleeding potential (P1); and lesions with no bleeding potential (P0). Positive WCE studies were defined as examinations that identified one or more P1 or P2 lesions, whereas those that identified only P0 or no abnormal lesions were regarded as negative WCE studies. Exclusion criteria were as follows: concomitant or not non-gastrointestinal blood loss (hematuria, hemoptyses and gynecological blood loss), incomplete exams (not reaching the ileocecal valve), poor preparation (as dictated by the examiner) and less than twelve months of follow-up. Negative WCE cases were selected and analyzed. A re-bleeding event was defined as occult re-bleeding [a decrease in 20 g/L of [Hb] - (serum hemoglobin) from the patient baseline] or overt re-bleeding (melena, hematochezia). Cases of re-bleeding due to non-small-bowel pathology (e.g., peptic ulcer disease, erosive esophagitis/gastritis/duodenitis, gastroesophageal varices, colorectal carcinoma, etc.) detected during follow-up were excluded from further analysis. The median follow-up for all patients strictly monitored for re-bleeding was forty-eight months (interquartile range 24-60). Study variables included the following: demographic data (patient age and gender), comorbidities (chronic kidney disease, aortic stenosis, prior diagnosis of angiodysplasia), relevant medication [use of anticoagulant, antiplatelet agent/s, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs)], hemoglobin level prior to WCE, indication for WCE (occult or overt - melena/hematochezia OGIB), time from OGIB detection to WCE procedure, post procedure details and follow-up [type of treatment for bleeding, hospital admissions (especially for anemia and/or recurrent gastrointestinal bleeding), blood transfusions, need for iron supplementation, additional endoscopies and surgery, re-bleeding causes (if determined) and patient status at the end of follow-up (on-going investigation or treated successfully)].

The Statistical Package for Social Science (version 20.0; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, United States) was used for all statistical analysis. Continuous variables are expressed as the mean ± SD or median (interquartile range) as appropriate. Qualitative and quantitative differences between subgroups were analyzed using the χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test for categorical parameters and Student’s t test or Mann-Whitney test for continuous parameters as appropriate. Univariate and multivariate analyses by Cox proportional hazards regression model was performed to identify factors associated with re-bleeding. After the univariate analysis, variables with a P < 0.05 were entered in the multivariate analysis. Effect sizes are expressed as hazard ratios (HRs) and 95%CIs. The Kaplan-Meier method was used to estimate the cumulative incidence of re-bleeding at 1, 3 and 5- years of follow-up, and differences between factors were evaluated using the log-rank test. All statistical tests were 2 sided. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

During the follow-up period, 640 patients were referred for OGIB investigation. In 113 exams (17.7%), the WCE could not find the culprit lesion and was deemed negative (P0 lesions or no abnormal findings). A summary of baseline characteristics is displayed in Table 1. Among the studied population, 73 patients were female (64.6%), with a median age of 69 years old (interquartile range 56-79); 62.8% (n = 71) of the patients were > 65 years old. Forty-five patients (39.8%) were taking bleeding-related drugs (single anti-platelet agent: n = 19 (16.8%); anticoagulant: n = 8 (7.1%); double anti-platelet agent: n = 6 (5.3%); non-steroidal anti-inflammatory (NSAIDs): n = 8 (7.1%); SSRI: n = 4 (3.5%). Thirty-five out of 113 (31%) presented with overt obscure bleeding (overt OGIB) - melena (n = 22; 19.5%) and hematochezia (n = 13; 11.5%).

| % (n) | |

| Age | |

| ≤ 65 years old | 37.2 (42) |

| > 65 years old | 62.8 (71) |

| Gender | |

| Female | 64.6 (73) |

| Male | 35.4 (40) |

| Comorbidities | |

| Chronic kidney disease | 12.4 (14) |

| Aortic stenosis | 6.3 (7) |

| Prior angiodysplasia | 3.5 (4) |

| Medication | |

| None relevant | 54 (61) |

| Single anti-platelet agent | 16.8 (19) |

| Anticoagulant | 7.1 (8) |

| NSAID | 7.1 (8) |

| Double anti-platelet agent | 5.3 (6) |

| SSRI | 3.5 (4) |

| Occult OGIB | 69 (78) |

| Iron deficiency anemia | 63 (71) |

| Overt OGIB | 31 (35) |

| Melena | 19.5 (22) |

| Hematochezia | 11.5 (13) |

| [Hb] prior to WCE (median; IQR; g/L) | 86 (70-100) |

| Transfusional needs prior to WCE (RBC units; median; IQR) | 1 (1-2) |

| Technical Issues | |

| Gastric Transit Time (min; median; IQR) | 18 (11-37) |

| Small-bowel Transit Time (min; median; IQR) | 253 (216-323) |

| WCE per Examiner (%) | |

| Person A | 42.5 (n = 48) |

| Person B | 38.9 (n = 44) |

| Person C | 9.7 (n = 11) |

| Person D | 8.9 (n = 10) |

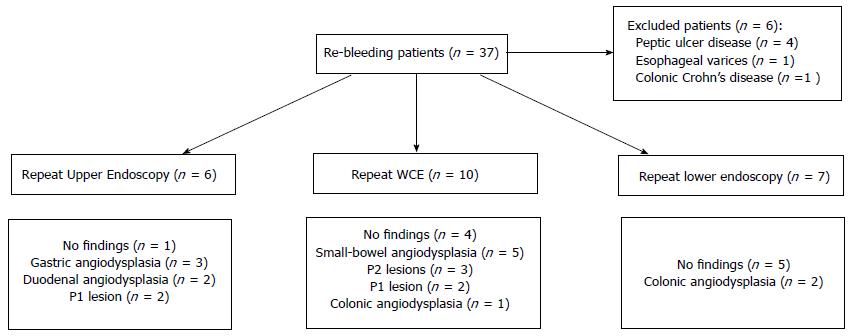

The median follow-up was forty-eight months (interquartile range 24-60). After the exclusion of re-bleeding cases due to non-small-bowel pathology, re-bleeding from the small-bowel (or unknown origin) occurred in thirty-one out of 113 negative WCE studies (27.4%). The median time from index negative WCE to the re-bleeding episode was 15 mo (interquartile range 2-33). Figure 1 provides data regarding endoscopic investigations in patients who re-bled and the associated causes. Among the re-bleeding cases, 29 (94%), were submitted to at least one additional endoscopic procedure. In ten re-bleeding cases (32%), the culprit lesion was/remains unknown; in thirteen cases (42%) an angiodysplasia (small-bowel n = 7, colon n = 3, stomach n = 3) was identified on a subsequent study. Half of the repeated WCE visualized a previously unrecognized small-bowel angiodysplasia. Of those who re-bled from a small-bowel angiodysplasia (n = 7), three (all P2 lesions; 43%) were submitted to argon-plasma thermocoagulation (APC) via deep enteroscopy (one patient received one APC session, one received two APC sessions and the other patient had to be submitted to five APC sessions), with complete resolution of the gastrointestinal bleeding. Among the total re-bleeding population, five patients (16%) received specific medical therapy (proton pump inhibitor and/or NSAIDs or anticoagulant withdrawal), three patients (9.7%) received non-specific medical therapy (iron supplementation or blood transfusions), and twenty patients (64.5%) did not receive any type of treatment.

Overall, at the end of the follow-up period, twenty-four patients with re-bleeding (77.4%) were considered successfully treated [i.e., despite the re-bleeding event they were asymptomatic, did not require a blood transfusion or iron supplementation and had a normal (Hb) level]. Seven patients (22.6%) remain under close follow-up (requiring regular iron supplementation, blood transfusions).

A comparison of baseline characteristics between re-bleeders vs non re-bleeders is summarized in Table 2. The results of univariate and multivariate analyses regarding factors associated with re-bleeding in patients with a negative WCE are summarized in Table 3. According to a univariate analysis, age > 65 years old, chronic kidney disease, aortic stenosis, anticoagulant use and overt OGIB were detected as factors associated with a significant risk of re-bleeding after a negative WCE. After subjecting the previous variables to a multivariate analysis using a Cox proportional hazards regression model, none of the previously identified factors were able to independently predict future re-bleeding events.

| Variable | All | Non re-bleeders | Re-bleeders | P |

| Age (years old) | 67 ± 15 | 65 ± 15 | 72 ± 11 | 0.007 |

| Gender (M/F) | 40/73 | 27/55 | 13/18 | 0.386 |

| OGIB presentation (n) | ||||

| Occult | 79 | 61 | 18 | 0.067 |

| Overt | 34 | 21 | 13 | |

| [Hb] (median) | 86 | 86 | 79 | 0.143 |

| Anticoagulant use (n) | 11 | 4 | 7 | 0.009 |

| Small-bowel Transit time (median) | 253 | 253.5 | 251.5 | 0.650 |

| Variables | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||||

| HR | 95%CI | P | HR | 95%CI | P | |

| Female | 1.408 | 0.676-2.929 | 0.361 | |||

| Age > 65 years old | 3.599 | 1.364-9.501 | 0.010 | 2.591 | 0.951-7.060 | 0.063 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 3.498 | 1.265-9.671 | 0.016 | 2.252 | 0.749-6.770 | 0.148 |

| Aortic stenosis | 4.159 | 1.412-12.247 | 0.010 | 1.548 | 0.352-6.811 | 0.563 |

| Prior angiodysplasia | 3.637 | 0.851-15.457 | 0.081 | |||

| Bleeding-related drugs | 1.586 | 0.761-3.304 | 0.219 | |||

| Anticoagulant use | 3.903 | 1.542-9.875 | 0.004 | 2.699 | 0.705-10.330 | 0.147 |

| Overt OGIB | 2.104 | 1.011-4.380 | 0.047 | 1.986 | 0.933-4.231 | 0.075 |

| [Hb] < 80 g/L | 1.857 | 0.868-3.970 | 0.111 | |||

| Transfusional (RBC) needs prior to WCE | 1.122 | 0.919-1.370 | 0.257 | |||

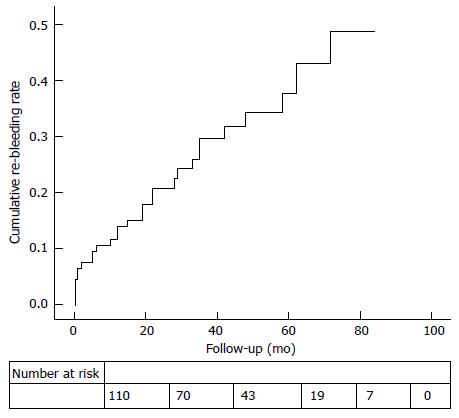

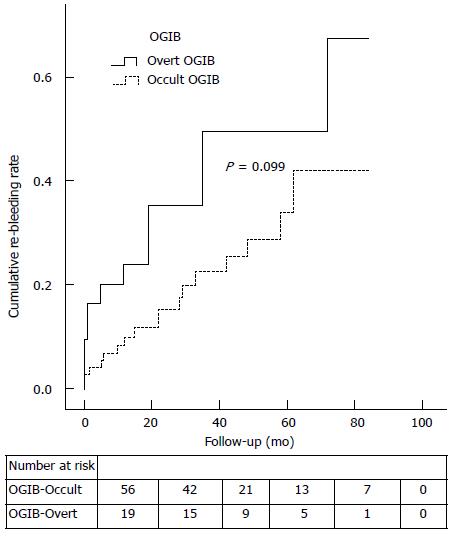

The overall cumulative risk of re-bleeding at 1, 3 and 5-year of follow-up was 12.9%, 25.6% and 31.5%, respectively (Figure 2). To perform a comprehensive analysis, a subgroup comparison between those who initially presented with occult OGIB vs overt OGIB is summarized in Table 4. The overt group tended to re-bleed sooner than the occult group (median time until re-bleeding event: 8.5 mo vs 22 mo; P = 0.257); however, re-bleeding rates between these two groups were not significantly different (Figure 3; P = 0.099).

| Variable | Occult OGIB | Overt OGIB | P |

| Age (years old) | 66 | 68 | 0.448 |

| Sex (M/F) | 24/54 | 16/19 | 0.141 |

| [Hb] (median) | 8.9 | 7.9 | 0.015 |

| Anticoagulant use (n) | 8 | 3 | 1.000 |

| Time from OGIB to WCE (d; median) | 31 | 29 | 0.653 |

| Follow-up period (mo; median) | 48 | 42 | 0.450 |

| Rebleeding cumulative events (at 12 mo) (n) | 9% (7) | 21% (7) | 0.133 |

| Rebleeding cumulative events (at 36 mo) (n) | 20% (13) | 39% (11) | |

| Rebleeding cumulative events (at 60 mo) (n) | 29% (16) | 39% (11) | |

| Rebleeding cumulative events (at 84 mo) (n) | 34% (17) | 49% (12) | |

| Rebleeding cumulative events (total) (n) | 17 | 12 | |

| Time to rebleeding event (mo; IQR) | 22 (6-33) | 8.5 (0.5-27) | 0.257 |

Capsule endoscopy revolutionized the world of gastrointestinal endoscopy, mainly OGIB, by allowing the gastroenterologist to identify the possible cause of OGIB and enhance a directional or specific treatment. Capsule endoscopy is a safe and effective technology in the evaluation of small-bowel pathology[1]. Whether a positive or negative WCE study impacts patient outcome remains ill defined. Two recent studies failed to demonstrate that a higher diagnostic yield is related to an improved outcome in patients with OGIB[19,20]. Moreover, on a recent nationwide study by Min et al[8], the authors concluded that WCE did not have a significant impact on the long-term outcome of patients with OGIB. Some studies analyzed the long-term outcome defining the occurrence of a re-bleeding event as a primary outcome[9-12,14,15,21]. In the paramount study of Lai et al[9], patients with a negative WCE study (n = 18) displayed a low re-bleeding rate (5.6%) when followed for twelve months (median). Another study by Macdonald et al[10] that analyzed 49 patients with OGIB (median follow-up = 17 mo) demonstrated a higher re-bleeding rate in this subgroup (negative WCE) of patients (11%) and, when assessing risk factors associated with re-bleeding, identified anticoagulant use as the only independent predictor. Therefore, these first two studies claimed a low re-bleeding probability in patients whose first WCE study was negative, thus advising an expectant approach. Thereafter, it has been postulated that a negative WCE result predicts a favorable prognosis in patients with OGIB and a low risk of re-bleeding. Later, a study by Park et al[12] with 51 patients followed for thirty-two months demonstrated a re-bleeding rate of 35.7% in WCE negative patients. Hence, the authors recommended a close follow-up of these patients for at least 2 years. Moreover, two of the most recent studies[14,19] report re-bleeding rates of 23% and 33%, respectively. Additionally, it has been demonstrated that there are no significant difference in the cumulative re-bleeding rates between patients with positive vs negative WCE findings[8,12,14].

In the present study, we focused on and followed 113 patients referred for OGIB investigation with a negative WCE. Similar to previous recent retrospective cohort studies[12,14], we demonstrated high re-bleeding rates (27.4%) in this group of patients when followed for longer periods (> 12 mo). Studies that reported lower re-bleeding rates had shorter follow-up periods[9,10,15,22]. To optimize the definition of the risk, we set the minimum follow-up period at 12 mo, and we obtained a median follow-up period of 48 mo (4 years). In approximately 1/3 of the re-bleeders, the culprit lesion remained unknown (i.e., persistently negative endoscopic studies), and when identified, angiodysplasia was the most frequent lesion (42%), mainly small-bowel angiodysplasia (53.8% of all the missed angiodysplasia), which is in line with a previous report[23]. One explanation for these findings might be that some angiodysplasias were missed in the first WCE (although some lesions may have developed after the index WCE). In addition, the natural history of such vascular lesions remains unclear, and their dynamic nature makes them hard to demonstrate consistently. Additionally, it is important to note that knowing that there is a positive correlation between diagnostic yield and small-bowel transit time (SBTT), especially in OGIB[24], as presented in Table 4, SBTT did not differ between re-bleeders and non-re-bleeders; therefore, it is unlikely that re-bleeders had a higher rate of important missed lesions than non-re-bleeders.

In Western countries, angiodysplasia seems to be more frequent than in Asia, and this might be another explanation for the lower re-bleeding rates observed across some of the Asian studies, where small-bowel ulcers dominate the OGIB etiology[8,22]. In patients with recurrent OGIB or IDA who had a negative WCE, a repeat WCE revealed the presence of angiodysplasia in up to 29% of patients (75% of all findings) and led to changes in patient management in two small studies[25,26], which is in line with our data.

Similarly to previous studies[14,15] our median time until re-bleeding was 15 mo, which strengthens the importance of closely following these patients in the first 2 years after index WCE and seemingly over the 3rd year, as our interquartile range for re-bleeding was between 2 and 33 mo. Although the results were not statistically significant (Figure 3; Log-Rank test = 0.099), when the subgroups of patients presenting with occult and overt OGIB were analyzed separately, we observed that patients who presented with overt OGIB, in contrast with the occult group, tended to re-bleed sooner (median time until re-bleeding = 8.5 mo vs 22 mo).

Previous studies pinpointed anticoagulant intake[10,14] as an independent risk factor for re-bleeding, regardless of WCE results. Others[15] identified younger age (< 65 years old) and the onset of bleeding as independent risk factors for re-bleeding after a negative WCE. Consistent with another recent study[23], our results showed that in a univariate analysis, patients who re-bled were older (HR = 3.599; 95%CI: 1.364-9.501; P = 0.010). One explanation is that the prevalence of angiodysplasia (the most frequent re-bleeding lesion in most studies) is known to be higher in older individuals[1], making them a group prone to re-bleeding. It is also known that the incidence of small-bowel vascular lesions (mainly angiodysplasia) in patients with chronic kidney disease is high[27-29], thus making them more likely to re-bleed, as shown in an univariate analysis (HR = 3.498; 95%CI: 1.265-9.671; P = 0.016). In our study, as demonstrated previously[14], taking anticoagulants is an important risk factor for re-bleeding (HR = 3.903; 95%CI: 1.542-9.875; P = 0.004). Another interesting finding was that even though patients who presented with an overt OGIB tended to re-bleed more than those who presented with occult OGIB (HR = 2.104; 95%CI: 1.011-4.380; P = 0.047), a statistically significant difference could not be found between the groups (Figure 3). Patients with aortic stenosis may have a higher prevalence of angiodysplasia (condition also known as Heyde Syndrome) through the gastrointestinal tract[30,31]. In patients with aortic stenosis, the tendency to harbor angiodysplasia in the gut may pose an elevated risk of re-bleeding events. In this study, there was a trend towards more re-bleeding events in these patients (HR = 4.159; 95%CI: 1.412-12.247; P = 0.010). However, when all of these factors were pooled on a multivariate analysis, their statistical significance became null.

Our study limitations were the following: (1) the data were collected from a single tertiary referral hospital and the study had a retrospective design; (2) some of the patients included are followed at other institutions; thus, some follow-up data are missing; and (3) we focused only on patients referred for OGIB with a negative WCE. A comparison of re-bleeding rates with positive WCE cases would have been interesting; however, in a recent study[8], it was demonstrated that re-bleeding rates between positive and negative WCE cases were not significantly different. A leverage point of our study was the very long-term post procedure follow-up period and the relatively large number of patients included.

In conclusion, patients with OGIB with a negative WCE have a significant re-bleeding risk (27.4%), and a follow-up strategy is recommended. In this study, predictive factors for re-bleeding events could not be found using a multivariate analysis; however, a tendency was demonstrated (older age, chronic kidney disease, aortic stenosis, anticoagulants use and overt OGIB), and in future series, a tailored approach/surveillance may be required. Prospective observational studies addressing this topic with long-term follow-up are urgently needed.

Obscure gastrointestinal bleeding (OGIB) is defined as occult or overt gastrointestinal bleeding of unknown origin that persists or recurs after initial negative endoscopic evaluation (esophagogastroduodenoscopy and colonoscopy). OGIB represents approximately 5% of all gastrointestinal bleeding cases, and the culprit lesion is located in the small-bowel in most instances. Angiodysplasias of the small-bowel account for 30% to 40% of OGIB. Wireless capsule endoscopy (WCE) is a safe and well-accepted technology that enables visualization of the small-bowel.

A negative (WCE) study remains a clinical challenge, and little is known about the long-term follow-up of such patients. The “protective effect” of a negative WCE study on future re-bleeding events remains controversial. To date, there are some conflicting data about the re-bleeding rates and predictive factors linked to a re-bleeding event, and in addition, median follow-up period varies among studies.

In a retrospective analysis, the authors evaluated the long-term re-bleeding events after a negative WCE in patients referred for OGIB. In a concrete and relatively large cohort from a tertiary center in Europe with long-term follow-up (48 mo), it was found that patients with OGIB, despite a negative WCE, have a significant re-bleeding rate (27.4%). Small-bowel angiodysplasia was the most frequent re-bleeding related lesion (22.6%). The median time from index negative WCE to the re-bleeding episode was fifteen months. After a multivariate analysis, there were no independent predictors for re-bleeding.

This study suggests that patients with OGIB and a first negative WCE should have an extended follow-up. Although independent predictors for re-bleeding were not found, physicians should recognize some important risk factors for re-bleeding (older age, chronic kidney disease, aortic stenosis, anticoagulants use and overt OGIB) and consider further endoscopic investigations if re-bleeding occurs.

OGIB is defined as bleeding from the gastrointestinal tract that persists or recurs without an obvious source being discovered by esophagogastroduodenoscopy, colonoscopy and radiologic evaluation of the small-bowel. Small-bowel capsule endoscopy uses a wireless miniature (pill sized) encapsulated video camera designed to visualize the entire small-bowel.

In a retrospective analysis the authors evaluated the long-term re-bleeding events after a negative wireless capsule endoscopy in patients referred for obscure gastrointestinal bleeding. They found that patients with obscure gastrointestinal bleeding, despite a negative capsule endoscopy, during a 48 mo mo follow-up period have a significant re-bleeding rate (27.4%). They concluded that there are no reliable risk factors that can predict a future re-bleeding event in these patients. The topic is interesting and suitable for publication.

P- Reviewer: Almeida N, Herszenyi L, Ianiro G, Koulaouzidis A, Kurtoglu E, Maehata Y, de Lange T S- Editor: Song XX

L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wu HL

| 1. | Raju GS, Gerson L, Das A, Lewis B. American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) Institute technical review on obscure gastrointestinal bleeding. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:1697-1717. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 379] [Cited by in RCA: 338] [Article Influence: 18.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Leighton JA, Goldstein J, Hirota W, Jacobson BC, Johanson JF, Mallery JS, Peterson K, Waring JP, Fanelli RD, Wheeler-Harbaugh J. Obscure gastrointestinal bleeding. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;58:650-655. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Marmo R, Rotondano G, Rondonotti E, de Franchis R, D’Incà R, Vettorato MG, Costamagna G, Riccioni ME, Spada C, D’Angella R. Capsule enteroscopy vs. other diagnostic procedures in diagnosing obscure gastrointestinal bleeding: a cost-effectiveness study. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;19:535-542. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Carey EJ, Leighton JA, Heigh RI, Shiff AD, Sharma VK, Post JK, Fleischer DE. A single-center experience of 260 consecutive patients undergoing capsule endoscopy for obscure gastrointestinal bleeding. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:89-95. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 214] [Cited by in RCA: 212] [Article Influence: 11.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Leighton JA, Triester SL, Sharma VK. Capsule endoscopy: a meta-analysis for use with obscure gastrointestinal bleeding and Crohn’s disease. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2006;16:229-250. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Liao Z, Gao R, Xu C, Li ZS. Indications and detection, completion, and retention rates of small-bowel capsule endoscopy: a systematic review. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;71:280-286. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 561] [Cited by in RCA: 475] [Article Influence: 31.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Pasha SF, Leighton JA, Das A, Harrison ME, Decker GA, Fleischer DE, Sharma VK. Double-balloon enteroscopy and capsule endoscopy have comparable diagnostic yield in small-bowel disease: a meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6:671-676. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 270] [Cited by in RCA: 272] [Article Influence: 16.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Min YW, Kim JS, Jeon SW, Jeen YT, Im JP, Cheung DY, Choi MG, Kim JO, Lee KJ, Ye BD. Long-term outcome of capsule endoscopy in obscure gastrointestinal bleeding: a nationwide analysis. Endoscopy. 2014;46:59-65. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Lai LH, Wong GL, Chow DK, Lau JY, Sung JJ, Leung WK. Long-term follow-up of patients with obscure gastrointestinal bleeding after negative capsule endoscopy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:1224-1228. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Macdonald J, Porter V, McNamara D. Negative capsule endoscopy in patients with obscure GI bleeding predicts low rebleeding rates. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;68:1122-1127. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Lorenceau-Savale C, Ben-Soussan E, Ramirez S, Antonietti M, Lerebours E, Ducrotté P. Outcome of patients with obscure gastrointestinal bleeding after negative capsule endoscopy: results of a one-year follow-up study. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 2010;34:606-611. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Park JJ, Cheon JH, Kim HM, Park HS, Moon CM, Lee JH, Hong SP, Kim TI, Kim WH. Negative capsule endoscopy without subsequent enteroscopy does not predict lower long-term rebleeding rates in patients with obscure GI bleeding. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;71:990-997. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Kim JB, Ye BD, Song Y, Yang DH, Jung KW, Kim KJ, Byeon JS, Myung SJ, Yang SK, Kim JH. Frequency of rebleeding events in obscure gastrointestinal bleeding with negative capsule endoscopy. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;28:834-840. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Koh SJ, Im JP, Kim JW, Kim BG, Lee KL, Kim SG, Kim JS, Jung HC. Long-term outcome in patients with obscure gastrointestinal bleeding after negative capsule endoscopy. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:1632-1638. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Riccioni ME, Urgesi R, Cianci R, Rizzo G, D’Angelo L, Marmo R, Costamagna G. Negative capsule endoscopy in patients with obscure gastrointestinal bleeding reliable: recurrence of bleeding on long-term follow-up. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:4520-4525. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Mishkin DS, Chuttani R, Croffie J, Disario J, Liu J, Shah R, Somogyi L, Tierney W, Song LM, Petersen BT. ASGE Technology Status Evaluation Report: wireless capsule endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;63:539-545. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 186] [Cited by in RCA: 169] [Article Influence: 8.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Saurin JC, Delvaux M, Gaudin JL, Fassler I, Villarejo J, Vahedi K, Bitoun A, Canard JM, Souquet JC, Ponchon T. Diagnostic value of endoscopic capsule in patients with obscure digestive bleeding: blinded comparison with video push-enteroscopy. Endoscopy. 2003;35:576-584. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 253] [Cited by in RCA: 314] [Article Influence: 14.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Gralnek IM, Defranchis R, Seidman E, Leighton JA, Legnani P, Lewis BS. Development of a capsule endoscopy scoring index for small bowel mucosal inflammatory change. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;27:146-154. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 284] [Cited by in RCA: 325] [Article Influence: 19.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Laine L, Sahota A, Shah A. Does capsule endoscopy improve outcomes in obscure gastrointestinal bleeding? Randomized trial versus dedicated small bowel radiography. Gastroenterology. 2010;138:1673-1680.e1; quiz e11-e12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Holleran GE, Barry SA, Thornton OJ, Dobson MJ, McNamara DA. The use of small bowel capsule endoscopy in iron deficiency anaemia: low impact on outcome in the medium term despite high diagnostic yield. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;25:327-332. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Delvaux M, Fassler I, Gay G. Clinical usefulness of the endoscopic video capsule as the initial intestinal investigation in patients with obscure digestive bleeding: validation of a diagnostic strategy based on the patient outcome after 12 months. Endoscopy. 2004;36:1067-1073. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 150] [Cited by in RCA: 136] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Pongprasobchai S, Chitsaeng S, Tanwandee T, Manatsathit S, Kachintorn U. Yield, etiologies and outcomes of capsule endoscopy in Thai patients with obscure gastrointestinal bleeding. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2013;5:122-127. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Cañas-Ventura A, Márquez L, Bessa X, Dedeu JM, Puigvehí M, Delgado-Aros S, Ibáñez IA, Seoane A, Barranco L, Bory F. Outcome in obscure gastrointestinal bleeding after capsule endoscopy. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2013;5:551-558. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Westerhof J, Koornstra JJ, Hoedemaker RA, Sluiter WJ, Kleibeuker JH, Weersma RK. Diagnostic yield of small bowel capsule endoscopy depends on the small bowel transit time. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:1502-1507. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Bar-Meir S, Eliakim R, Nadler M, Barkay O, Fireman Z, Scapa E, Chowers Y, Bardan E. Second capsule endoscopy for patients with severe iron deficiency anemia. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;60:711-713. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Jones BH, Fleischer DE, Sharma VK, Heigh RI, Shiff AD, Hernandez JL, Leighton JA. Yield of repeat wireless video capsule endoscopy in patients with obscure gastrointestinal bleeding. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:1058-1064. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 89] [Cited by in RCA: 85] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Kawamura H, Sakai E, Endo H, Taniguchi L, Hata Y, Ezuka A, Nagase H, Kessoku T, Yamada E, Ohkubo H. Characteristics of the small bowel lesions detected by capsule endoscopy in patients with chronic kidney disease. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2013;2013:814214. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Holleran G, Hall B, Hussey M, McNamara D. Small bowel angiodysplasia and novel disease associations: a cohort study. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2013;48:433-438. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Karagiannis S, Goulas S, Kosmadakis G, Galanis P, Arvanitis D, Boletis J, Georgiou E, Mavrogiannis C. Wireless capsule endoscopy in the investigation of patients with chronic renal failure and obscure gastrointestinal bleeding (preliminary data). World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:5182-5185. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Heyde EC. Gastrointestinal bleeding in aortic stenosis. N Engl J Med. 1958;259:196. |

| 31. | Williams RC Jr. Aortic stenosis and unexplained gastrointestinal bleeding. Arch Intern Med. 1961;108:859-863. |