Published online Dec 25, 2015. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v7.i19.1350

Peer-review started: April 8, 2015

First decision: May 14, 2015

Revised: June 30, 2015

Accepted: July 16, 2015

Article in press: July 17, 2015

Published online: December 25, 2015

Processing time: 260 Days and 3.1 Hours

Endoscoic variceal ligation (EVL) by the application of bands on small bowel varices is a relatively rare procedure in gastroenterology and hepatology. There are no previously reported paediatric cases of EVL for jejunal varices. We report a case of an eight-year-old male patient with a complex surgical background leading to jejunal varices and short bowel syndrome, presenting with obscure but profound acute gastrointestinal bleeding. Wireless capsule endoscopy and double balloon enteroscopy (DBE) confirmed jejunal varices as the source of bleeding. The commercially available variceal banding devices are not long enough to be used either with DBE or with push enteroscopes. With the use of an operating gastroscope, four bands were placed successfully on the afferent and efferent ends of the leads of the 2 of the varices. Initial hemostasis was achieved with obliteration of the varices after three separate applications. This case illustrates the feasibility of achieving initial hemostasis in the pediatric population.

Core tip: Banding jejunal varices in the pediatric population is feasible, safe and can achieve initial hemostasis in complex surgical patients.

- Citation: Belsha D, Thomson M. Challenges of banding jejunal varices in an 8-year-old child. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2015; 7(19): 1350-1354

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v7/i19/1350.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v7.i19.1350

Ectopic varices are defined as large porto-systemic venous collaterals occurring anywhere in the abdomen except in the cardio-esophageal region[1].

They account for up to 5% of all variceal bleeding[2]. Ectopic varices have been reported to occur at numerous sites, including 18% in the jejunum or ileum, 17% in the duodenum, 14% in the colon, 8% in the rectum, and 9% in the peritoneum[3]. Jejunal variceal bleeding, although rare, can be life threatening. There are only a few reports on the managements of jejunal varices in the paediatric population[4]. We present a rare case of severe and recurrent gastrointestinal bleeding secondary to jejunal varices in an 8-year-old patient. The management strategies including the use of endoscopic variceal ligation (EVL) are discussed.

An 8-year-old male patient was transferred from another tertiary hospital for assessment for obscure but profound acute gastrointestinal bleeding (AGIB).

He had a complex background of gastroschisis at birth associated with duodenal and colonic atresia. He had a repair of gastroschisis on day 1 of life and subsequently underwent a duodenojejunal anastamosis with right hemicolectomy and ileostomy formation, followed by ileo-colonic anastamosis and closure of the stoma. He had short gut syndrome and received nutritional supplementation via a balloon gastrostomy.

He had had multiple episodes of GI bleeding since he was 18 mo of age, which were thought to be associated with a superior mesenteric vein thrombosis. These were intermittent in nature and managed conservatively. The patient had a period of two years without a GI bleed prior to this presentation.

In 2014 however, the patient had 17 episodes of AGIB. Seven episodes were significant, mainly of hematochezia with clots or large melena. His lowest recorded hemoglobin was 22 g/L. The patient had multiple blood transfusions and was given 4 weekly iron infusions. He underwent computed tomography (CT) angiography which revealed distorted adjacent vascular structures around the pancreas with the splenic vein looping over the superior edge of the pancreas.

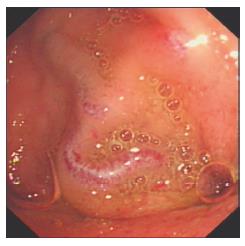

Normal enhancement was noticed in the portal vein, its left and right branches, the splenic vein (SV) and the superior mesenteric vein (SMV). However; there is unusual prominent venous structure draining in to the right side of the confluence of the SMV and the SV. There were multiple serpiginous vessels in the left side of the bowel mesentery with in particular a clump of varices/collaterals in the small bowels mesentery (Figure 1). All connections from these apparent varices couldn’t be established, however; there was at least a connection to a looping vessel which extends into the left side of the SMV. Further looping vessels were seen in the anterior aspect of the mesentery from a proximal loop of the jejunum. Theses dilated blood vessels and collaterals around the mesentery of the small bowel raised the suspicion of mesenteric varices in the upper abdomen, but no active bleeding source was recognised. The patient was put intermittently on octreotide infusion but wasn’t given primary or secondary prophylaxis as it was felt that the varices were more confined to some areas and secondary to mesenteric venous obstruction/ abnormalities rather than strong evidence of generalised portal hypertension.

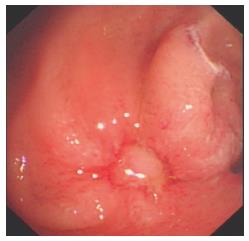

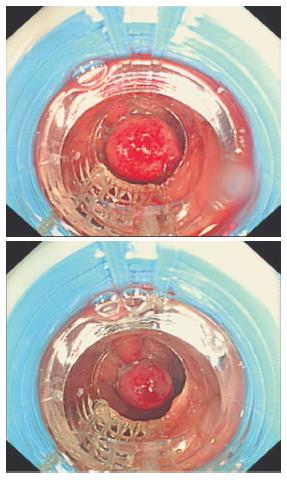

On arrival to our hospital in the same year, upper GI endoscopy revealed no esophago-gastric varices but identified portal gastropathy. Ileo-colonoscopy was normal apart from an erythematous ileo-colonic anastamotic rim. WCE identified a suspicious area (around 50 cm from the pylorus) of nodular shaped lesions with bluish discoloration, suspicious of varices. Two days later, further profound hematochezia occurred and therefore octreotide infusion (5 mcg/kg per hour) was commenced. Trans-oral double balloon enteroscopy (DBE) confirmed a normal esophagus, mild evidence of portal gastropathy, a normal duodenum, and jejunal examination revealed 4 moderately large isolated jejunal varices around 40-50 cm post-pylorus (Figures 2 and 3). Four bands were placed successfully on the afferent and efferent ends of the leads of the 2 of the varices using an operating gastroscope (Figure 4). The commercially available variceal banding devices are not long enough to be used either with DBE which was initially used diagnostically. Trans-anal DBE was performed and showed a small potential varix approximately 120 cm proximal to the ileo-colonic anastamosis and this was not considered a risk and was not bleeding therefore was not banded. This area was marked for future reference with methylene blue tattoo injection. One week later a further endoscopy revealed the 2 banded varices to be thrombosed and now absent and sloughing within the bands was noted which were beginning to fall off the mucosa. The remaining 2 variceal vessels were then also banded. Two weeks subsequently the patient was well with no further bleed and a further endoscopy revealed friable variceal beds but no active bleeding. One further varix was banded at that time with hemostasis identified.

However the patient developed recurrence of bleed two weeks later possibly from an ileo-colonic source. The patient had shunting procedure few weeks later (mesenterico-caval shunt).

Our patient presented with the classical clinical signs reported previously in the literature for jejunal varices, evidence of abnormal vasculature in the mesentery with or without portal hypertention, a history of abdominal surgery, and hematochezia with or without hematemesis[5].

The exact pathology for developing jejunal varices in our case is not fully understood. It is likely to be a combination of superior mesenteric vein thrombosis (subsequently re-canalised however) and adhesions. A history of abdominal surgery appears to predispose to the development of ectopic varices around adhesions[6]. It seems that small-bowel anastomotic and adhesion-related varices can form within adhesions in the setting of mesenteric venous obstruction with or without portal hypertension[5].

Collateral formation within adhesions from previous surgery is the usual mechanism for the development of ectopic varices[3], with a likely mechanism that adhesions bring the parietal surface of the viscera in contact with the abdominal wall and portal hypertension results in the formation of varices below the intestinal mucosa[7].

The mainstay for the diagnosis of jejunal varices in our case was a combination of CT angiography and wireless capsule endoscopy.

Jejunal varices in wireless capsule endoscopy appear as serpiginous or nodular shapes, with or without a bluish discoloration. The variceal mucosa appears mosaic-like, shining, or normal compared with surrounding mucosa[8].

Capsule endoscopy is invaluable for the diagnosis of small-bowel varices. It is highly sensitive for detecting fresh blood in the small bowel. Clinical suspicion, capsule endoscopy image recognition, and alertness during capsule endoscopy interpretation are keys to diagnosis[8].

Several approaches for the treatment of jejunal varices have been described including surgery[9], portal venous stenting[10-12], percutaneous embolisation[13,14] and thne endoscopic options[5,15-18].

Surgical treatment options for small bowel variceal bleeds include resection of the afferent area of bowel and re-anastomosis[13]. However this can be challenging in patients with short gut and multiple adhesion as in our case.

Transjugular intrahepatic portal-systemic shunt or a decompressive shunting procedure is recommended in patients with overt systemic portal hypertension[13,19,20]. With the addition of coil or embolization has been reported to be particularly useful for ectopic varices, as these can continue to bleed despite successful portal pressure reduction[21].

The effectiveness of beta-blockers for primary prophylaxis and octreotide treatment for acute hemorrhage of anastomotic and segmental varices is uncertain[5].

It has been reported that endoscopic treatment including sclerosing agents can be used for treatment of actively bleeding duodenal or jejunal varices or to prevent re-bleeding from focal varices with hemorrhage. However, while hemostasis is feasible, ulceration and re-bleeding rates can be high[5]. The use of N-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate (Histoacryl®) injection has been described in several case reports, for hemostasis of actively bleeding duodenal varices[15,22,23]. In one series all the varices had developed around the anastamotic sites and only two had elevated systemic portal pressure[18]. Another case report describes successful treatment of bleeding jejunal varices using cyanoacrylate sclerotherapy via enteroscopy in an adult patient[16].

EVL has a theoretical increased risk of complications in the small bowel because of its thin wall, e.g., perforation. However, there are several reports of successfully treated duodenal varices by EVL in adults without complications. In a review of 19 cases (all adults) with duodenal EVL only 3 (15.8%) rebled after treatment with no deaths reported due to complications or rebleeding[16]. In a report of 4 patients with duodenal EVL, 2 achieved complete resolution of varices after one treatment session, one had remaining varices on surveillance endoscopy but no bleeding in a 9 mo period and one case required surgical resection after several banding sessions[17].

The standard ligation balloon devices available are too short to be adapted for an enteroscope or a colonoscope but are applicable to standard upper GI endsocopes. The operating gastroscope (GIF-2TQ260M) allowed 3 way tip deviation and is stiffer than conventional upper GI endsocopes allowing successful banding to occur.

In this case, EVL was used successfully to achieve initial hemostasis with obliteration of the varices after three separate applications, however bleeding subsequently occurred from an ileo-colonic source.

Frequently ectopic variceal bleeding is difficult to manage and traditionally surgery or shunting is required depending on the underlying disease and the patency of the portal vein.

Endoscopic treatment as a minimally invasive approach is feasible and safe in this case and represents a viable alternative.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first reported case in the literature describing EVL in the management of jejunal variceal bleeding in the pediatric population.

This case illustrates the technical feasibility and apparent safety of EVL in the management of jejunal variceal bleeding in children.

Recurrent severe gastrointestinal bleeding.

Jejunal varices.

Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy ruled out esophageal and gastric variceal bleeding. Ilio-colonosconoscopy and wireless capsule ruled out other diagnosis like polyps or other vascular malformation. Wireless capsule showed features suggestive of ectopic varices.

Extensive investigations including complete blood count, Lipase, liver enzymes, kidney function, radiological images with computed tomography (CT) angiography. The diagnosis was confirmed with wireless capsule endoscopy and endoscopy of the affected small bowel.

Imaging study using CT scan demonstrated thickening and irregularity of the mesentery surrounding in keeping with the diagnosis of mesenteric panniculitis.

Variceal bleeding was the diagnosis as per the wireless capsule endoscopy and the endoscopic finding.

The patient was treated with pharmacological agents including octreotide. Blood transfusion was needed frequently to stabilise the patient. Endoscopic variceal ligation was successfully applied to achieve initial hemostasis.

Clark et al reported successful endoscopic ectopic variceal ligation: A series of 4 cases and review of the literature in adult population.

Jejunal varices is a rare disorder that can present with recurrent severe gastrointestinal bleeding in complex surgical paediatric patient, the authors describe a novel intervention in paediatric using endoscopic variceal ligation to achieve initial hemostasis.

In this case report the authors present the case of an 8-year-old child treated with endoscopic band ligation for jejunal varices. This kind of pathology is rare and the therapeutic options could be challenging.

P- Reviewer: Abu-Zidan FM, Kaehler G, Procopet B S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Lu YJ

| 1. | Rockey DC. Occult and obscure gastrointestinal bleeding: causes and clinical management. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;7:265-279. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Akhter NM, Haskal ZJ. Diagnosis and management of ectopic varices. Gastrointestinal Intervention. 2012;1:3-10. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 3. | Lebrec D, Benhamou JP. Ectopic varices in portal hypertension. Clin Gastroenterol. 1985;14:105-121. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Thomas V, Jose T, Kumar S. Natural history of bleeding after esophageal variceal eradication in patients with extrahepatic portal venous obstruction; a 20-year follow-up. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2009;28:206-211. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Tang SJ, Jutabha R, Jensen DM. Push enteroscopy for recurrent gastrointestinal hemorrhage due to jejunal anastomotic varices: a case report and review of the literature. Endoscopy. 2002;34:735-737. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Sharma D, Misra SP. Ectopic varices in portal hypertension. Indian J Surg. 2005;67:246-252. |

| 7. | Sato T, Akaike J, Toyota J, Karino Y, Ohmura T. Clinicopathological features and treatment of ectopic varices with portal hypertension. Int J Hepatol. 2011;2011:960720. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (35)] |

| 8. | Tang SJ, Zanati S, Dubcenco E, Cirocco M, Christodoulou D, Kandel G, Haber GB, Kortan P, Marcon NE. Diagnosis of small-bowel varices by capsule endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;60:129-135. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Yuki N, Kubo M, Noro Y, Kasahara A, Hayashi N, Fusamoto H, Ito T, Kamada T. Jejunal varices as a cause of massive gastrointestinal bleeding. Am J Gastroenterol. 1992;87:514-517. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Sakai M, Nakao A, Kaneko T, Takeda S, Inoue S, Yagi Y, Okochi O, Ota T, Ito S. Transhepatic portal venous angioplasty with stenting for bleeding jejunal varices. Hepatogastroenterology. 2005;52:749-752. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Hiraoka K, Kondo S, Ambo Y, Hirano S, Omi M, Okushiba S, Katoh H. Portal venous dilatation and stenting for bleeding jejunal varices: report of two cases. Surg Today. 2001;31:1008-1011. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Ota S, Suzuki S, Mitsuoka H, Unno N, Inagawa S, Takehara Y, Sakaguchi T, Konno H, Nakamura S. Effect of a portal venous stent for gastrointestinal hemorrhage from jejunal varices caused by portal hypertension after pancreatoduodenectomy. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2005;12:88-92. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Lim LG, Lee YM, Tan L, Chang S, Lim SG. Percutaneous paraumbilical embolization as an unconventional and successful treatment for bleeding jejunal varices. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:3823-3826. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Sasamoto A, Kamiya J, Nimura Y, Nagino M. Successful embolization therapy for bleeding from jejunal varices after choledochojejunostomy: report of a case. Surg Today. 2010;40:788-791. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Paterlini A, Rolfi F, Buffoli F, Cesari P, Graffeo M, Benedini D, Lanzani G, Bonera E. Endoscopic treatment of a bleeding duodenal varix using N-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate. Endoscopy. 1993;25:434. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Gunnerson AC, Diehl DL, Nguyen VN, Shellenberger MJ, Blansfield J. Endoscopic duodenal variceal ligation: a series of 4 cases and review of the literature (with video). Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;76:900-904. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Getzlaff S, Benz CA, Schilling D, Riemann JF. Enteroscopic cyanoacrylate sclerotherapy of jejunal and gallbladder varices in a patient with portal hypertension. Endoscopy. 2001;33:462-464. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Gubler C, Glenck M, Pfammatter T, Bauerfeind P. Successful treatment of anastomotic jejunal varices with N-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate (Histoacryl): single-center experience. Endoscopy. 2012;44:776-779. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Stafford Johnson DB, Narasimhan D. Case report: successful treatment of bleeding jejunal varices using mesoportal recanalization and stent placement: report of a case and review of the literature. Clin Radiol. 1997;52:562-565. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Shibata D, Brophy DP, Gordon FD, Anastopoulos HT, Sentovich SM, Bleday R. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt for treatment of bleeding ectopic varices with portal hypertension. Dis Colon Rectum. 1999;42:1581-1585. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Tripathi D, Jalan R. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic stent-shunt in the management of gastric and ectopic varices. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;18:1155-1160. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Yoshida Y, Imai Y, Nishikawa M, Nakatukasa M, Kurokawa M, Shibata K, Shimomukai H, Shimano T, Tokunaga K, Yonezawa T. Successful endoscopic injection sclerotherapy with N-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate following the recurrence of bleeding soon after endoscopic ligation for ruptured duodenal varices. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997;92:1227-1229. [PubMed] |