Published online Jan 16, 2015. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v7.i1.66

Peer-review started: August 30, 2014

First decision: November 3, 2014

Revised: November 10, 2014

Accepted: December 16, 2014

Article in press: December 17, 2014

Published online: January 16, 2015

Processing time: 139 Days and 20.6 Hours

AIM: To investigate whether dysplastic Barrett’s Oesophagus can be safely and effectively treated endoscopically in low volume centres after structured training.

METHODS: After attending a structured training program in Amsterdam on the endoscopic treatment of dysplastic Barrett’s Oesophagus, treatment of these patients was initiated at St Marys Hospital. This is a retrospective case series conducted at a United Kingdom teaching Hospital, of patients referred for endoscopic treatment of Barrett’s oesophagus with high grade dysplasia or early cancer, who were diagnosed between January 2008 and February 2012. Data was collected on treatment provided (radiofrequency ablation and endoscopic resection), and success of treatment both at the end of treatment and at follow up. Rates of immediate and long term complications were assessed.

RESULTS: Thirty-two patients were referred to St Marys with high grade dysplasia or intramucosal cancer within a segment of Barrett’s Oesophagus. Twenty-seven met the study inclusion criteria, 16 of these had a visible nodule at initial endoscopy. Treatment was given over a median of 5 mo, and patients received a median of 3 treatment sessions over this time. At the end of treatment dysplasia was successfully eradicated in 96% and intestinal metaplasia in 88%, on per protocol analysis. Patients were followed up for a median of 18 mo. At which time complete eradication of dysplasia was maintained in 86%. Complications were rare: 2 patients suffered from post-procedural bleeding, 4 cases were complicated by oesophageal stenosis. Recurrence of cancer was seen in 1 case.

CONCLUSION: With structured training good outcomes can be achieved in low volume centres treating dysplastic Barrett’s Oesophagus.

Core tip: With structured training endoscopic treatment of dysplastic Barrett’s Oesophagus with endoscopic resection and radiofrequency ablation can be provided in lower volume centres with good safety and efficacy outcomes.

- Citation: Chadwick G, Faulkner J, Ley-Greaves R, Vlavianos P, Goldin R, Hoare J. Treatment of dysplastic Barrett’s Oesophagus in lower volume centres after structured training. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2015; 7(1): 66-72

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v7/i1/66.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v7.i1.66

Barrett’s Oesophagus is a significant risk factor for oesophageal cancer[1], with studies suggesting it develops through a dysplasia-carcinoma sequence[2]. As it does the risk of progression to cancer increases from 0.1% per year for a non-dysplastic segment of Barrett’s Oesophagus[3], to 5.6% per year if high grade dysplasia (HGD) is present[4].

United Kingdom guidelines recommend that Barrett’s Oesophagus should be regularly surveyed, with prompt intervention if there is progression to HGD or cancer[5]. Until recently esophagectomy has been considered the treatment of choice, but this is associated with significant morbidity and mortality even in high volume centres[6]. Over recent years significant progress has been made in the endoscopic treatment of Barrett’s Oesophagus with dysplastic changes. This has resulted in the most recent United Kingdom guidelines recommending endoscopic treatment of HGD in preference to oesophagectomy, given the lower treatment related morbidity[5].

Endoscopic treatment of dysplastic Barrett’s oe-sophagus has two important stages. First, removal of any visible dysplastic lesions. This is usually achieved by endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) of the lesion; this provides definitive staging information and ensures that lesions extending into the submucosa are not missed. Once this is done, it is recommended that any remaining segment of Barrett’s Oesophagus is treated, this minimises the risk development of cancer in the future in the remaining Barrett’s segment[7]. Two distinct approaches can be taken to do this, stepwise radical endoscopic resection (SRER) or ablation of the affected mucosa. Over the last five years radiofrequency ablation (RFA) has become the most widely used ablative technique. A recent systematic review demonstrated that while SRER and RFA have similar efficacy in treating dysplastic Barrett’s Oesophagus, RFA is associated with a significantly lower rate of complications[8]. Furthermore while SRER appears to be a relatively complex technique to learn[9], learning to perform RFA does not appear to be associated with such a significant learning curve[10]. Ablation is therefore generally accepted as the preferred treatment modality in Europe.

To date most of the studies looking at the endoscopic treatment of Barrett’s Oesophagus have come from high volume research centres, with only one small retrospective study coming from a community hospital in the United States[11]. This study reported 100% success in eradication of dysplasia at follow up in 10 patients with HGD, suggesting that dysplastic Barrett’s Oesophagus can be managed successfully outside of large volume research centres. But larger studies performed outside high volume research centres are still needed.

Given the rapidly rising incidence of oesophageal cancer and Barrett’s Oesophagus in the United Kingdom[12,13], several smaller centres have established treatment programs for dysplastic Barrett’s Oesophagus. Recognising this fact the Academic Medical Centre in Amsterdam (AMC) created a multidisciplinary European Training Program for the treatment of neoplasia within Barrett’s Oesophagus[14]. The aim of this course was to improve the quality of detection and treatment of dysplastic Barrett’s Oesophagus in these lower volume centres.

This study aims to assess whether with the structured training, endoscopists with little experience in ablative techniques can be taught to manage dysplastic Barrett’s Oesophagus safely and effectively in lower volume centres.

In 2008 a centre for the treatment of dysplastic Barrett’s

oesophagus was established at St Mary’s, a United Kingdom teaching hospital and regional centre for upper gastro-intestinal surgery. Patients were included in this retrospective consecutive case series, if they were diagnosed with Barrett’s Oesophagus with HGD or intramucosal cancer (IMC) between January 2008 and February 2012 and were referred to St Marys for endoscopic treatment.

All patients had their pre-treatment histological diagnosis confirmed by a specialist pathologist (RG), and were discussed at the local specialist multi-disciplinary team (MDT) meeting, to determine the most appropriate treatment course. Any further staging investigations including CT and EUS recommended by the MDT to rule out invasive cancer, were performed at this stage.

Patients were identified for inclusion in the study by searching the hospital’s electronic endoscopy database (Ascribe), records were cross checked against pathology records and MDT meeting reports to ensure no cases were missed. Patients were excluded from this study if there was evidence of sub-mucosal invasion on resection of any visible nodules, or if they were considered unfit for repeated therapeutic endoscopies.

Prior to the commencement of the study period, a multi-disciplinary team from St Marys, consisting of an endoscopist (JH), a pathologist (RG) and an endoscopy nurse attended the European training program for Barrett’s Oesophagus with neoplasia at the AMC. The course consisted of three two day workshops, these combined theoretical lectures, live demonstrations by experts and finally hands on supervised training sessions. The hands on sessions were staged, starting treatment on explanted pig tissue, before progressing to live pigs and then human cases. A variety of different endoscopic techniques were taught including EMR-cap, multiband mucosectomy and RFA.

All endoscopic procedures were performed by one of two experienced endoscopists (JH, PV) on an outpatient basis under conscious sedation. All procedures were performed using an Olympus H260Z series endoscope, with narrow band imaging and zoom features used at the operators discretion.

Visible areas of dysplasia were resected first, using the DuetteTM Multiband Mucosectomy (Cook Medical, Winston-Salem, NC). Patients with evidence of sub-mucosal invasion on the resected specimen were referred back to the MDT, and excluded from the study at this stage. Remaining patients had a repeat endoscopy two months later, where a further resection was performed if required. Otherwise patients were considered for ablation of any residual Barrett’s Oesophagus using RFA. Patients with dysplasia detected within a segment of flat Barrett’s Oesophagus on initial endoscopy started treatment with RFA immediately.

RFA was performed using the HALO system (BARRX Medical, Sunnyvale, CA). Circumferential RFA (HALO360) was usually applied first, using standard energy settings (12 J/cm2, 40 W/cm2). This was repeated after repositioning the balloon, until the entire Barrett’s Oesophagus segment was ablated. The catheter was then removed, so debris could be scraped off the balloon and coagulum could be removed from the ablation zone. The process was then repeated, before ablating the segment a second time. If there was only a short segment of non-circumferential Barrett’s Oesophagus present initially or on follow up procedures, focal ablation was applied using the HALO90 device. RFA was then delivered twice in quick succession to each area (12-15 J/cm2, 40 W/cm2), then the probe and the mucosa were cleaned, the area was then ablated again twice. In the interest of costs, argon plasma coagulation (APC) was used at the endoscopist’s discretion to treat small islands (< 5 mm) of residual Barrett’s Oesophagus. Patients received treatment at 2-3 monthly intervals until all visible Barrett’s Oesophagus was eradicated.

At this stage treatment was considered complete and targeted biopsies were taken of any endoscopic abnormalities in the oesophagus, and quadrantic biopsies were taken from just distal (< 5 mm) to the neo-squamocolumnar junction (NSCJ).

All histological specimens were analysed by a specialist gastrointestinal pathologist (RG), and if there was evidence of dysplasia the diagnosis was confirmed by a second pathologist. Biopsies were assessed using the revised Vienna classification[15].

Data was collected retrospectively from endoscopy reports and pathology records, up to August 2013. Information was collected on patient demographics, length of the Barrett’s Oesophagus segment treated, the number and type of procedures each patient had had, duration of follow up and complications related to the procedure. Histology records provided information on pre and post treatment histology.

The primary outcome assessed was success of complete eradication of dysplasia (CE-D) and intestinal metaplasia (CE-IM) after completion of treatment. This was defined as absence of any endoscopically visible Barrett’s Oesophagus (confirmed on available oesophageal biopsies), combined with the absence of dysplasia on biopsies taken from just distal to the NSCJ.

Secondary endpoints: (1) Rate of CE-D/CE-IM at most recent follow-up endoscopy, more than 6 mo after completion of treatment. Follow-up duration was defined as the time between completion of treatment and the most recent follow up endoscopy; (2) Rates of short term complications, related to initial endoscopic procedure, e.g., bleeding or perforation; and (3) Rates of long term complications associated with the endoscopic treatment, e.g., oesophageal stenosis.

Results are presented on both a per protocol (PP) and an intention to treat (ITT) basis, for the primary outcome and complication rates. But follow up results are presented on intention to follow up basis, after excluding patients who did not complete endoscopic treatment (due to patient choice or failure of endoscopic treatment) and patients who had not completed 6 mo follow up.

The study did not use any biostatistics mathods.

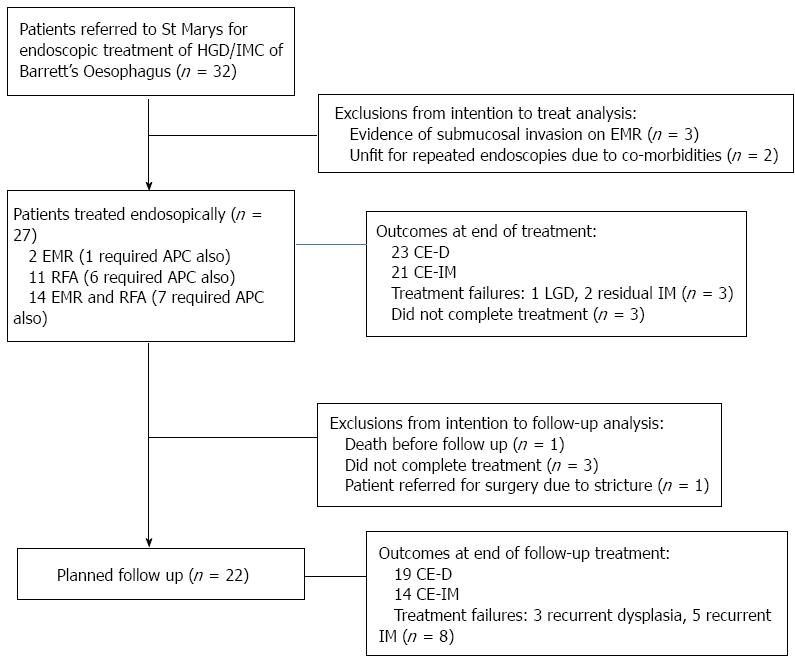

Between January 2008 and February 2012, 32 patients were referred for endoscopic treatment of Barrett’s Oesophagus with HGD or IMC.

Twenty-one of these patients had a nodule visible endoscopically at referral. Of these, 3 patients were found to have lesions extending deep into the submucosa, and an additional 2 patients were considered unfit for repeated endoscopic therapy due to severe co-morbidities. As a result these 5 patients were excluded from analysis.

This left 27 patients who met the inclusion criteria, and were considered for this study (Figure 1). Patient demographics are summarised in Table 1.

| Male: female | 25:2 |

| Median age (yr) (range) | 66 (53-89) |

| Median length Barrett’s (cm) (range) | 5 (1-10) |

| Worst diagnosis on biopsy or ER specimen | 9 IMC/18 HGD |

Patients received treatment over a median of 5 mo. During this time the median number of treatment sessions required was 3 (range 1-9). Where RFA was used, patients required a median of 1 focal and 1 circumferential ablation.

Sixteen patients (59%), including all those with a known diagnosis of IMC, had a nodule visible at initial endoscopy which was resected. Four of these patients required a further endoscopic resection, during the treatment period. Following successful endoscopic resection, 14 patients received additional treatment with RFA to treat the remaining Barrett’s Oesophagus.

While 11 patients were found to have evidence of dysplasia within a flat segment Barrett’s Oesophagus, they were treated with RFA alone as the primary therapy.

Following EMR and RFA, additional treatment with APC was needed in 14 patients, to treat small areas of residual Barrett’s Oesophagus.

On an ITT basis CE-D at the end of treatment was achieved in 85% (23/27) CE-D, while 78% (21/27) achieved CE-IM. But 3 patients did not complete treatment as planned, so for the 24 patients who completed treatment as planned CE-D was achieved in 96% (23/24), with only 1 patient having evidence of residual low grade dysplasia (LGD). A further 2 patients who completed their planned treatment had evidence of visible non-dysplastic Barrett’s Oesophagus after completing treatment, so CE-IM was achieved in 88% (21/24) of the cohort on PP analysis.

One patient who did not complete planned treatment was lost to follow up, after failing to attend several appointments. He represented 2 years later with a T2 oesophageal cancer, this was treated with an oesophagectomy but he subsequently died. The other two patients were lost to follow up, despite multiple attempts to re-engage them.

Follow up results: 22 patients were considered for analysis in the follow up cohort. The 5 patients who were dropped from this cohort included the 3 patients who had failed to complete treatment, 1 who died from pancreatic cancer before starting follow up and 1 patient was referred for surgery after endoscopic treatment failed and resulted in a severe stricture refractory to endoscopic dilatation. The median follow up duration was 18 mo (range 7-34 mo).

During follow up 3 patients had recurrence of dysplasia. One patient had recurrent IMC, this has been retreated endoscopically and the patient is awaiting follow up. One patient who had LGD at the end of treatment progressed to HGD during follow up. This patient is now undergoing regular surveillance instead of further treatment, on account of their co-morbidities and wishes. The final patient who developed LGD during follow up is undergoing more intense surveillance, but has not received further treatment. So overall 19/22 (86%) patients achieved CE-D at the most recent follow up.

A further 5 patients had recurrence of visible non-dysplastic Barrett’s Oesophagus during follow up, so CE-IM was maintained in 14/22 (64%).

Overall 6 patients suffered from complications related to the procedure (22%). Two patients suffered acute bleeding post EMR, both were successfully treated endoscopically.

A further four (14.8%) patients developed oesophageal stenosis during follow up, all had had a prior EMR. This was treated successfully with endoscopic dilatation in three patients (two patients required a single dilatation, but one patient required three dilatations). The final patient, treated midway through the study, had five attempts at dilatation but the stricture was refractory to treatment, this patient was referred for an oesophagectomy which confirmed there was no evidence of residual disease.

There were no fatalities or oesophageal perforations related to treatment.

Given the high morbidity and mortality associated with oesophagectomy, endoscopic treatment for Barrett’s Oesophagus with HGD or IMC is now considered the treatment of choice in most patients[5,16]. To date these treatments have been provided predominantly by high volume research centres. However, with the increasing prevalence of oesophageal cancer and Barrett’s Oesophagus in Europe[12], an increasing number of lower volume treatment centres are being established. As a result the AMC in Amsterdam developed a specialised training program aimed at optimising the recognition and treatment of dysplastic Barrett’s Oesophagus in these centres. It is therefore important to establish whether similar outcomes, in terms of both treatment efficacy and complication rates, can be achieved in lower volume centres after attending such a program.

This retrospective case series started with the first case of dysplastic Barrett’s Oesophagus treated at our institution after attending the course, and demonstrates that EMR and RFA for dysplastic Barrett’s Oesophagus can be safely performed in lower volume institutions outside of a research setting.

Analysis of outcomes focused on the rates of eradication of dysplasia and intestinal metaplasia at the end of treatment and at follow up. For this analysis we considered presence of dysplasia on biopsies taken below the neo-squamocolumnar junction as evidence of treatment failure, because studies have suggested the risk of recurrence of dysplasia is highest in this area and may predict development of neoplasia[17,18]. But presence of intestinal metaplasia alone below the NSCJ was not considered significant, as the relevance of this finding is debatable. Morales et al[19] demonstrated the presence of intestinal metaplasia in routine biopsies taken from the cardia in 25% of a healthy population, suggesting the finding is not clinically relevant[19].

Overall treatment was very successful in patients who completed treatment as planned, with 100% success in eradication of HGD and IMC, 96% success in eradication of any dysplasia and 88% success in eradicating visible Barrett’s Oesophagus. These results are comparable to previous studies, with prospective studies from large volume tertiary referral centres reporting between 81%-100% CE-D and 74%-100% CE-IM at the end of treatment[20-24].

One of the major drawbacks of studies to date has been the short follow up periods reported, between 14 and 22 mo[20-24]. This study provides a median follow up of 18 mo. Overall durability of eradication of dysplasia was good, with 86% of patients maintaining complete eradication of dysplasia at the end of treatment. Previous studies had reported 79%-100% CE-D at follow up[20-22,25,26].

Currently St Marys is a relatively low volume centre, with only 32 new patients considered for treatment during the 4 year study period (equating to less than 1 new patient per month). So our patient volumes are likely to be similar to those reported by centres involved in the United Kingdom HALO registry. This registry collected data from 216 patients recruited from 14 United Kingdom centres, and reported the following outcomes at the end of treatment: 83% CE-HGD, 76% CE-D and 50% CE-IM[27]. It is uncertain what initial training endoscopists had at each centre involved in this study. But our comparatively favourable results suggest that access to a specialised training program may have a beneficial impact on treatment outcomes, and allow lower volume centres to provide access to high quality endoscopic treatment for dysplastic Barrett’s Oesophagus.

Throughout this series there were no reported deaths or perforations, but two patients required endoscopic treatment for bleeding post EMR. A further four patients (14.8%) suffered late complications, due to oesophageal stenosis. Our overall rates of oesophageal stenosis was slightly higher than rates reported in previous studies (0%-14%)[20-23,26,28,29]. This can be explained by two factors, firstly the relatively high proportion of patients (59%) who required EMR prior to use of RFA (it should be noted that all strictures in this study occurred in patients who had had a previous EMR) and secondly this series started with the first case treated by our endoscopists. Van Vilsteren et al[9] previously demonstrated that there is a significant learning curve associated with learning to perform oesophageal EMR, and noted that complication rates were highest for the first few therapeutic en-doscopies performed[9].

In conclusion, this study demonstrates that following structured training good outcomes can be achieved in the endoscopic treatment of dysplastic Barrett’s Oesophagus in lower volume centres. While our rate of oesophageal stenosis was slightly higher than previously reported, it must be noted that these results represent the start of our learning curve. We therefore expect this rate to fall as the endoscopist’s experience increases.

Barrett’s Oesophagus is a pre-malignant condition which progresses through a dysplasia-carcinoma sequence. As it does the risk of progression to cancer increases rapidly. It is therefore important to treat patients with evidence of high grade dysplasia as they are at higher risk of developing oesophageal cancer. Until recently oesophagectomy has been the mainstay of treatment this is associated with significant risk, and therefore used predominantly in younger fitter patients. But recently newer endoscopic techniques have been developed with proven safety and efficacy in treating dysplastic Barrett’s Oesophagus.

With the increasing incidence of Barrett’s Oesophagus in the United Kingdom it is important to assess whether these endoscopic techniques can be used safely and effectively outside of research centres, where the majority of the current literature is derived.

Several large studies have already demonstrated the safety and efficacy of endoscopic resection and radiofrequency ablation in dysplastic Barrett’s Oesophagus (as summarised in a review by Chadwick et al). But these studies have come from high volume research centres. This is the first study to demonstrate that with structured training clinicians can achieve good outcomes in the endoscopic treatment of dysplastic Barrett’s Oesophagus in low volume centres.

The results of this study suggest that with structured training, endoscopic treatment of dysplastic Barrett’s can be used safely and effectively in lower volume hospitals.

Barrett’s Oesophagus: This is the replacement of the normal stratified epithelium lining of the lower oesophagus with columnar cells. This is important because it puts the person at increased risk of development of oesophageal cancer; Dysplasia: Refers to the development of abnormal epithelium, which in the case of Barrett’s Oesophagus is at risk of progression to cancer; Intramucosal oesophageal cancer: Cancer affecting the very superficial layer of the oesophagus. This stage of cancer is at low risk of spreading to the regional lymph nodes and distant organs; Endoscopic Mucosal Resection: A procedure to remove cancerous or other abnormal tissues (lesions) using an endoscope which is passed down the oesophagus. Radiofrequency ablation is the use of high frequency current to destroy areas of abnormal tissue.

This article is really very interesting.

P- Reviewer: Dhalla SS, Souza JLS S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Zhang DN

| 1. | Spechler SJ, Robbins AH, Rubins HB, Vincent ME, Heeren T, Doos WG, Colton T, Schimmel EM. Adenocarcinoma and Barrett’s esophagus. An overrated risk? Gastroenterology. 1984;87:927-933. |

| 2. | Hameeteman W, Tytgat GN, Houthoff HJ, van den Tweel JG. Barrett’s esophagus: development of dysplasia and adenocarcinoma. Gastroenterology. 1989;96:1249-1256. |

| 3. | Hvid-Jensen F, Pedersen L, Drewes AM, Sørensen HT, Funch-Jensen P. Incidence of adenocarcinoma among patients with Barrett’s esophagus. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:1375-1383. |

| 4. | Rastogi A, Puli S, El-Serag HB, Bansal A, Wani S, Sharma P. Incidence of esophageal adenocarcinoma in patients with Barrett’s esophagus and high-grade dysplasia: a meta-analysis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;67:394-398. |

| 5. | Fitzgerald RC, di Pietro M, Ragunath K, Ang Y, Kang JY, Watson P, Trudgill N, Patel P, Kaye PV, Sanders S. British Society of Gastroenterology guidelines on the diagnosis and management of Barrett’s oesophagus. Gut. 2014;63:7-42. |

| 6. | Wouters MW, Wijnhoven BP, Karim-Kos HE, Blaauwgeers HG, Stassen LP, Steup WH, Tilanus HW, Tollenaar RA. High-volume versus low-volume for esophageal resections for cancer: the essential role of case-mix adjustments based on clinical data. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15:80-87. |

| 7. | May A, Gossner L, Pech O, Fritz A, Günter E, Mayer G, Müller H, Seitz G, Vieth M, Stolte M. Local endoscopic therapy for intraepithelial high-grade neoplasia and early adenocarcinoma in Barrett’s oesophagus: acute-phase and intermediate results of a new treatment approach. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2002;14:1085-1091. |

| 8. | Chadwick G, Groene O, Markar SR, Hoare J, Cromwell D, Hanna GB. Systematic review comparing radiofrequency ablation and complete endoscopic resection in treating dysplastic Barrett’s esophagus: a critical assessment of histologic outcomes and adverse events. Gastrointest Endosc. 2014;79:718-731.e3. |

| 9. | van Vilsteren FG, Pouw RE, Herrero LA, Peters FP, Bisschops R, Houben M, Peters FT, Schenk BE, Weusten BL, Visser M. Learning to perform endoscopic resection of esophageal neoplasia is associated with significant complications even within a structured training program. Endoscopy. 2012;44:4-12. |

| 10. | Zemlyak AY, Pacicco T, Mahmud EM, Tsirline VB, Belyansky I, Walters A, Heniford BT. Radiofrequency ablation offers a reliable surgical modality for the treatment of Barrett’s esophagus with a minimal learning curve. Am Surg. 2012;78:774-778. |

| 11. | Lyday WD, Corbett FS, Kuperman DA, Kalvaria I, Mavrelis PG, Shughoury AB, Pruitt RE. Radiofrequency ablation of Barrett’s esophagus: outcomes of 429 patients from a multicenter community practice registry. Endoscopy. 2010;42:272-278. |

| 12. | Alexandropoulou K, van Vlymen J, Reid F, Poullis A, Kang JY. Temporal trends of Barrett’s oesophagus and gastro-oesophageal reflux and related oesophageal cancer over a 10-year period in England and Wales and associated proton pump inhibitor and H2RA prescriptions: a GPRD study. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;25:15-21. |

| 13. | Cancer Research UK Statistical Information. Oesophageal Cancer Statistics. [Accessed May 2013]. Available from: http://www.cancerresearchuk.org/cancer-info/cancerstats/types/oesophagus. |

| 14. | EMR and RFA Training program 2008. [Accessed July 2014]. Available from: http://www.endosurgery.eu/html/homepage.htm. |

| 15. | Schlemper RJ, Riddell RH, Kato Y, Borchard F, Cooper HS, Dawsey SM, Dixon MF, Fenoglio-Preiser CM, Fléjou JF, Geboes K. The Vienna classification of gastrointestinal epithelial neoplasia. Gut. 2000;47:251-255. |

| 16. | Bennett C, Vakil N, Bergman J, Harrison R, Odze R, Vieth M, Sanders S, Gay L, Pech O, Longcroft-Wheaton G. Consensus statements for management of Barrett’s dysplasia and early-stage esophageal adenocarcinoma, based on a Delphi process. Gastroenterology. 2012;143:336-346. |

| 17. | Halsey KD, Chang JW, Waldt A, Greenwald BD. Recurrent disease following endoscopic ablation of Barrett’s high-grade dysplasia with spray cryotherapy. Endoscopy. 2011;43:844-848. |

| 18. | Chai NL, Linghu EQ. Which is the optimal treatment for Barrett’s esophagus with high grade dysplasia--ablation or complete endoscopic removal? Endoscopy. 2012;44:218; author reply 219. |

| 19. | Morales TG, Sampliner RE, Bhattacharyya A. Intestinal metaplasia of the gastric cardia. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997;92:414-418. |

| 20. | van Vilsteren FG, Pouw RE, Seewald S, Alvarez Herrero L, Sondermeijer CM, Visser M, Ten Kate FJ, Yu Kim Teng KC, Soehendra N, Rösch T. Stepwise radical endoscopic resection versus radiofrequency ablation for Barrett’s oesophagus with high-grade dysplasia or early cancer: a multicentre randomised trial. Gut. 2011;60:765-773. |

| 21. | Pouw RE, Wirths K, Eisendrath P, Sondermeijer CM, Ten Kate FJ, Fockens P, Devière J, Neuhaus H, Bergman JJ. Efficacy of radiofrequency ablation combined with endoscopic resection for barrett’s esophagus with early neoplasia. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;8:23-29. |

| 22. | Gondrie JJ, Pouw RE, Sondermeijer CM, Peters FP, Curvers WL, Rosmolen WD, Krishnadath KK, Ten Kate F, Fockens P, Bergman JJ. Stepwise circumferential and focal ablation of Barrett’s esophagus with high-grade dysplasia: results of the first prospective series of 11 patients. Endoscopy. 2008;40:359-369. |

| 23. | Gondrie JJ, Pouw RE, Sondermeijer CM, Peters FP, Curvers WL, Rosmolen WD, Ten Kate F, Fockens P, Bergman JJ. Effective treatment of early Barrett’s neoplasia with stepwise circumferential and focal ablation using the HALO system. Endoscopy. 2008;40:370-379. |

| 24. | Shaheen NJ, Sharma P, Overholt BF, Wolfsen HC, Sampliner RE, Wang KK, Galanko JA, Bronner MP, Goldblum JR, Bennett AE. Radiofrequency ablation in Barrett’s esophagus with dysplasia. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:2277-2288. |

| 25. | Shaheen NJ, Overholt BF, Sampliner RE, Wolfsen HC, Wang KK, Fleischer DE, Sharma VK, Eisen GM, Fennerty MB, Hunter JG. Durability of radiofrequency ablation in Barrett’s esophagus with dysplasia. Gastroenterology. 2011;141:460-468. |

| 26. | Sharma VK, Jae Kim H, Das A, Wells CD, Nguyen CC, Fleischer DE. Circumferential and focal ablation of Barrett’s esophagus containing dysplasia. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:310-317. |

| 27. | Haidry RJ, Dunn J, Banks M, Gupta A, Butt MA, Smart H, Bhandari P, Smith L-A, Willert R, Fullarton G. PWE-028 HALO radiofrequency ablation for high grade dysplasia and early mucosal neoplasia arising in Barrett’s oesophagus: interim results form the UK HALO radiofrequency ablation registry. Gut. 2012;61:A308. |

| 28. | Kim HP, Bulsiewicz WJ, Cotton CC, Dellon ES, Spacek MB, Chen X, Madanick RD, Pasricha S, Shaheen NJ. Focal endoscopic mucosal resection before radiofrequency ablation is equally effective and safe compared with radiofrequency ablation alone for the eradication of Barrett’s esophagus with advanced neoplasia. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;76:733-739. |

| 29. | Ganz RA, Overholt BF, Sharma VK, Fleischer DE, Shaheen NJ, Lightdale CJ, Freeman SR, Pruitt RE, Urayama SM, Gress F. Circumferential ablation of Barrett’s esophagus that contains high-grade dysplasia: a U.S. Multicenter Registry. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;68:35-40. |