Published online Jun 16, 2014. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v6.i6.260

Revised: May 8, 2014

Accepted: May 16, 2014

Published online: June 16, 2014

Processing time: 117 Days and 1.1 Hours

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) is an important diagnostic and therapeutic modality for various pancreatic and biliary diseases. The most common ERCP-induced complication is pancreatitis, whereas hemorrhage, cholangitis, and perforation occur less frequently. Early recognition and prompt treatment of these complications may minimize the morbidity and mortality. One of the most serious complications is perforation. Although the incidence of duodenal perforation after ERCP has decreased to < 1.0%, severe cases still require prolonged hospitalization and urgent surgical intervention, potentially leading to permanent disability or mortality. Surgery remains the mainstay treatment for perforations of the luminal organs of the gastrointestinal tract. However, evidence from case reports and case series support a beneficial role of endoscopic clipping in the closure of these defects. Duodenal fistulas are usually a result of sphincterotomies, perforated duodenal ulcers, or gastrectomy. Other causative factors include Crohn’s disease, trauma, pancreatitis, and cancer. The majority of duodenal fistulas heal with nonoperative management. Those that fail to heal are best treated with gastrojejunostomy. Recently proposed endoscopic approaches for managing gastrointestinal leaks caused by fistulas include fibrin glue injection and positioning of endoclips. Our patient developed a secondary persistent duodenal fistula as a result of previous incomplete closure of duodenal perforation with hemoclips and an endoloop. The fistula was successfully repaired by additional clipping and fibrin glue injection.

Core tip: In this report, a patient developed a secondary persistent duodenal fistula following an incomplete endoscopic closure of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography-related duodenal perforation with hemoclips and an endoloop. The fistula was successfully managed by further endoscopic treatment with additional clipping and fibrin glue injection. This case emphasizes that endoscopists should remain aware of the possibility for a secondary persistent fistula formation due to incomplete closure when long-standing fluctuating free air is detected after endoscopic treatment of bowel perforation.

- Citation: Yu DW, Hong MY, Hong SG. Endoscopic treatment of duodenal fistula after incomplete closure of ERCP-related duodenal perforation. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2014; 6(6): 260-265

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v6/i6/260.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v6.i6.260

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), an important technique used for diagnosis and therapeutic modality of various pancreatic and biliary diseases, is plagued by serious complications that can lead to significant morbidity. Overall, complications occur in 5%-10% of cases following ERCP with or without sphincterotomy[1]. The incidences of post-ERCP pancreatitis, hemorrhage, cholangitis, and perforation are 3.5%-3.8%, 0.9%-1.3%, 1.0%-5.0%, and 0.1%-1.1%, respectively. The overall mortality rate after ERCP is 0.3%[2,3]. Early recognition and prompt treatment of these complications may minimize the morbidity and mortality. One of the most feared complications is perforation. Perforation management depends on the location, radiologic imaging findings, and severity of the injury. The majority of duodenal fistulas are surgical complications caused by inadequate closure or devascularization of the duodenum. Other causative factors include Crohn’s disease, trauma, peptic ulcer disease, pancreatitis, and cancer[4]. The treatment of choice for patients with duodenal perforation is primary surgical closure. There have been reported cases of endoscopic closures of ERCP-related duodenal perforations using hemoclips[5]. Despite various strategies, from a minimally invasive approach with nutritional support to a more risky open surgery, duodenal fistulas remain difficult to treat[6].

To the best of our knowledge, there has been only one previously published report on a secondary duodenal fistula after ERCP-related duodenal perforation[7]. Recently, a patient in our care experienced a case of duodenal perforation following ERCP. Despite immediate application of multiple hemoclips and an endoloop to close the defect, a secondary persistent duodenal fistula, communicating with the peritoneal cavity, developed due to incomplete primary endoscopic closure. The fistula was successfully treated by further endoscopic treatment with additional clipping and fibrin glue injection.

A 66-year-old woman was admitted to our emergency department complaining of upper abdominal pain and vomiting, which occurred 3 h prior to her admission. On physical examination, her blood pressure was 130/75 mmHg, heart rate was 93 beats/min, and body temperature was 36.8 °C. Palpation revealed tenderness in the right upper quadrant of the abdomen. Laboratory test results were as follows: hemoglobin concentration, 11.5 g/dL; white blood cell count, 6800 cells/μL; aspartate aminotransferase, 222 IU/L; alanine aminotransferase, 86 IU/L; total bilirubin, 0.6 mg/dL; alkaline phosphatase, 49 IU/L; and gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase, 52 IU/L.

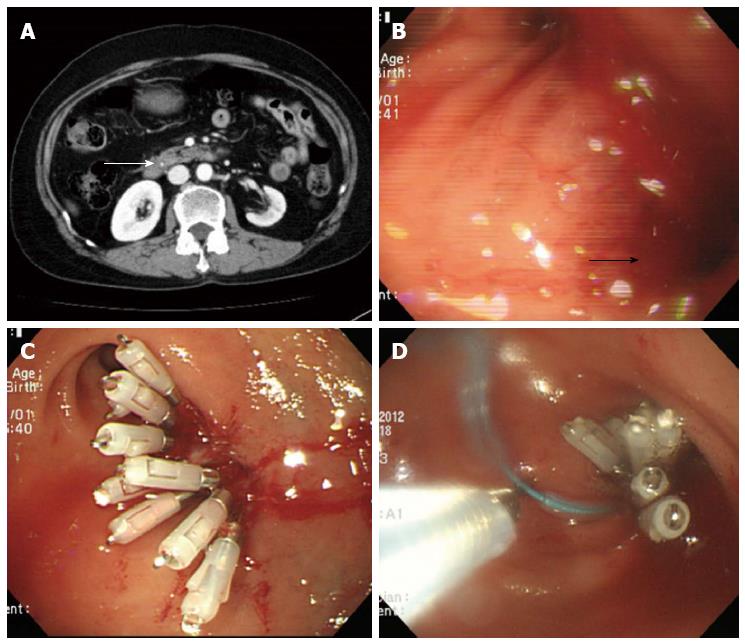

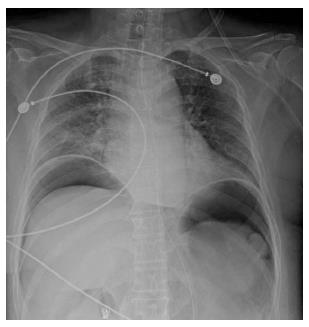

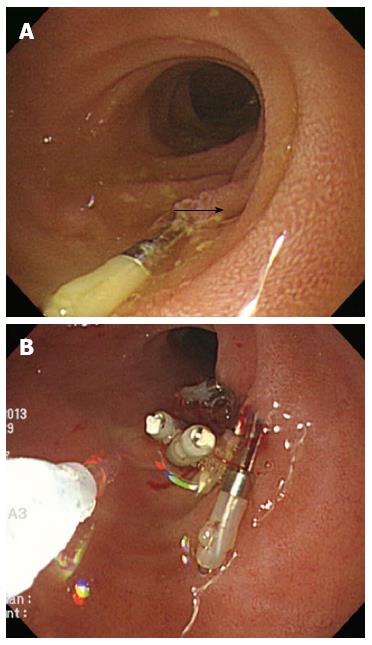

On the initial abdominal computed tomography (CT), a small (approximately 4 mm) distal common bile duct (CBD) stone was suspected. ERCP was performed on the day of admission (Figure 1A). While placing the scope in a short scope position, the scope was rapidly withdrawn into the pylorus and an approximately 10 mm linear perforation occurred in the lateral wall of the duodenal bulb. Multiple hemoclips (Olympus Corp., Tokyo, Japan) with a detachable plastic snare (Endoloop; Olympus Corp.) were immediately applied to close the perforation (Figure 1B-D). The patient developed chills and diffuse abdominal pain; the chest X-ray showed free air under both hemidiaphragms (Figure 2). Following ERCP, laboratory test results were as follows: hemoglobin concentration, 10.7 g/dL white blood cell count, 7900 cells/μL; aspartate aminotransferase, 485 IU/L; alanine aminotransferase, 438 IU/L; total bilirubin, 0.9 mg/dL; alkaline phosphatase, 59 IU/L; C-reactive protein (CRP), 81 mg/L; amylase, 32 IU/L; and lipase 25.7 IU/L. Nil per os was initiated with peripheral parenteral nutrition, intravenous broad spectrum antibiotic administration, and nasogastric tube drainage.

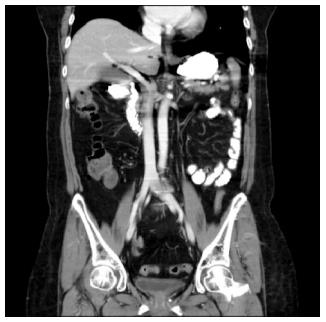

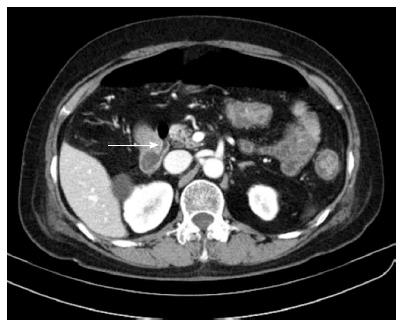

Abdominal pain was relieved on the sixth day after the endoscopic treatment, and the amount of free air under both hemidiaphragms was decreased on the chest X-ray. The laboratory test results showed that liver function was normalized and the CRP level decreased to 32.3 mg/L. The patient remained symptom-free for 3 d, and was permitted to take sips of water on the ninth day after duodenal perforation. Although the serum CRP level did not increase, the chest X-ray showed increased free air under both hemidiaphragms two days later. A follow-up CT scan with oral contrast (Gastrografin) showed no contrast leakage, however, it did show moderate amount of pneumoperitoneum (Figure 3). To determine if surgery was needed, a surgeon was consulted and the decision was made to continue conservative management for one more week. Although the patient remained symptom-free during this one-week period, the second follow-up CT showed a small fistula, approximately 2 mm in diameter, communicating with the peritoneal cavity at the prior perforation site in the duodenum (Figure 4). The previous CBD stone was not observed, and we presumed the stone had passed spontaneously. The serum CRP level was nearly normalized. With patient and medical guardian’s consent, a decision was made to perform endoscopic treatment before the operation. The secondary duodenal fistula was successfully closed using endoscopic treatment with additional clipping and fibrin glue (Greenplast®) injection (Figure 5). The free air under both hemidiaphragms significantly decreased the day after the endoscopic treatment, and the patient resumed a scheduled diet followed by a discharge three weeks after the development of duodenal perforation.

Although ERCP-related perforation is reported in less than 1% of cases, mostly due to sphincterotomy, perforation needs to be diagnosed immediately and treated promptly. Delays in the diagnosis and intervention of the perforation may lead to the development of sepsis and multiorgan failure, resulting in high mortality (8%-23%)[8-10]. The most commonly used classification of ERCP-induced perforations, suggested by Stapfer et al[11], is based on the mechanism of perforation and forecasts the need for surgery depending on the anatomic location and severity of injury. Another classification proposed by Howard et al[12] categorizes ERCP-induced perforation into three types: guidewire, periampullary, and duodenal perforation.

The treatment of post-ERCP perforation should be determined based on the type, the severity of the leak, and clinical manifestations. In our case, the perforation was classified as type I using Stapfer’s classification. Type I injury is caused by the endoscopic tip or insertion tube resulting in a large perforation requiring immediate surgery. However, if immediate treatment by endoscopic technique is not possible, conservative management with close monitoring may be a better option[9-11]. Sphincterotomy-related, guide-wire-related, or stent-related perforations can be treated by the endoscopic method with adequate ductal drainage above the perforation site[9,11]. In previous case reports, ERCP-related duodenal perforations were managed successfully with the use of endoclips[5,13]. However, adequate closure required inclusion of the bowel wall submucosal layer, which clips cannot reliably ensure. The patients need to be carefully selected, since the method is applicable to small, early detected, and well-defined perforations, which meet all the criteria for conservative management such as the absence of abdominal signs and fluid collections.

Our patient was immediately treated with endoscopy using multiple hemoclips and fibrin glue injection despite the perforation being relatively large (approximately 10 mm) for endoscopic closure. Although the endoscopy went well, a persistent secondary duodenal fistula, communicating with the peritoneal cavity, was observed on repeat CTs. Furthermore, free air was detected under the hemidiaphragms, despite the lack of extravasation of the contrast and the typical abdominal pain associated with the condition. An explanation for the free air is that it leaked from the fistula.

Gastrointestinal fistulas that result from surgery, disease, or trauma, are first treated medically. This includes parenteral nutrition and bowel rest, as well as control of infection, correction of electrolyte imbalance, and local care of the fistula tract. Patients with obstruction of the intestinal lumen downstream of the fistula or patients who have a persistent fistula, which fails to close after prolonged medical treatment, require surgical treatment[4,6]. Recently, various endoscopic approaches have been proposed for managing gastrointestinal leaks caused by fistulas, including fibrin glue injection, endoclip positioning, suturing devices, stent insertion, and endoluminal vacuum devices[14-16].

Fibrin glue, a formulation made up of glue and thrombin, is applied by a double injector system to repair tears. Mixing of these two components results in a fibrin coagulum formation with a short onset time. Fibrin injection can be used for sealing only very small leaks (< 5 mm diameter) not connected to the cavities, and in the absence of abscesses[17]. In a retrospective analysis of 52 patients with fistulas and anastomotic leakages in the gastrointestinal tract, endoscopic treatment was successful in 56% of cases. The success rate for fibrin glue application as the sole endoscopic therapy was 37%[16]. In short, endoscopic treatment with fibrin glue should be considered as a valuable option for treating fistula and anastomotic leakage of the gastrointestinal tract.

Standard clips are widely used in endoscopy for mechanical hemostasis following post-procedural bleeding. The importance of their role in endoscopic closure of small perforations, immediately following polypectomy or mucosectomy, is widely recognized. However, data on the endoclip efficacy in treating post-surgical leaks and fistulas are variable. Furthermore, the low closure strength of endoclips limits their use in scarred and hardened post-surgical tissues. To overcome this limitation, a new over-the-scope clip system (OTSC; Ovesco Endoscopy AG, Tubingen, Germany), consisting of a large nitinol clip loaded on the tip of the endoscope, has recently been developed. This device enables capturing of a large amount of tissue, powerfully compressing and approximating the margins of a lesion, thus favoring its healing[14,18].

CBD stones, especially the small ones, may pass spontaneously in a significant number of patients[19,20]. The absence of a stone in the patient’s CBD on follow-up CT could be explained by its spontaneous passage. Contrast leakage was not observed at the previous perforation site after endoscopic closure on the second follow-up CT. However, the leakage of air into the peritoneal space could have occurred through the secondary small fistula due to prior inadequate closure. Consequently, delayed formation of a secondary fistula should be considered in the presence of long-term, fluctuating free air under the diaphragm, viewed on abdominal imaging, following the endoscopic treatment.

In summary, despite the initial endoscopy treatment with hemoclips and an endoloop, a secondary persistent duodenal fistula developed due to incomplete previous endoscopic closure of the duodenal perforation after ERCP. Additional clipping and fibrin glue injections were successful in closing of the fistula.

Diffuse abdominal discomfort after endoscopic closure of the endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP)-related perforation with no specific symptom six days after ERCP.

Failure or inadequacy of endoscopic treatment for ERCP-related duodenal perforation.

Residual common bile duct stone or periduodenal abscess formation at the perforation site was possible.

C-reactive protein was elevated after ERCP-related perforation followed by a decrease six days after endoscopic treatment.

A secondary duodenal fistula formation into the peritoneal cavity on abdominal computed tomography (CT) due to inadequate primary endoscopic treatment for ERCP-related perforation.

After failed endoscopic closure of the ERCP-related duodenal perforation and the secondary fistula formation at the perforation site on abdominal CT 16 d after ERCP, a rescue endoscopic treatment with hemoclips and fibrin glue was successfully achieved, and persistent free air on chest X-ray disappeared a day after the rescue treatment.

The retroperitoneal duodenal perforation after biliary sphincterotomy led to development of the secondary duodenal fistula, refractory to laparotomy and drainage with conservative treatment, which was successfully managed with biliary self-expandable metallic stent insertion.

Fibrin glue, a biologic tissue adhesive, is made up of fibrinogen and thrombin, and has been used endoscopically for the treatment of bleeding, fistulas, and anastomotic leak.

Clinicians should consider the possibility of a secondary fistula formation into the peritoneal cavity, due to the presence of persistent fluctuating free air on chest X-ray after endoscopic treatment of a bowel perforation.

A very clear and concise case presentation. Well-structured and correctly documented. It is an interesting experience and we appreciate for sharing it with the readers.

P- Reviewers: Arezzo A, Budimir I, Perju-Dumbrava D S- Editor: Song XX L- Editor: A E- Editor: Zhang DN

| 1. | Freeman ML. Adverse outcomes of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography: avoidance and management. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2003;13:775-798, xi. |

| 2. | Anderson MA, Fisher L, Jain R, Evans JA, Appalaneni V, Ben-Menachem T, Cash BD, Decker GA, Early DS, Fanelli RD. Complications of ERCP. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;75:467-473. |

| 3. | Christensen M, Matzen P, Schulze S, Rosenberg J. Complications of ERCP: a prospective study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;60:721-731. |

| 4. | Babu BI, Finch JG. Current status in the multidisciplinary management of duodenal fistula. Surgeon. 2013;11:158-164. |

| 5. | Lee TH, Bang BW, Jeong JI, Kim HG, Jeong S, Park SM, Lee DH, Park SH, Kim SJ. Primary endoscopic approximation suture under cap-assisted endoscopy of an ERCP-induced duodenal perforation. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:2305-2310. |

| 6. | González-Pinto I, González EM. Optimising the treatment of upper gastrointestinal fistulae. Gut. 2001;49 Suppl 4:iv22-iv31. |

| 7. | Vezakis A, Fragulidis G, Nastos C, Yiallourou A, Polydorou A, Voros D. Closure of a persistent sphincterotomy-related duodenal perforation by placement of a covered self-expandable metallic biliary stent. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:4539-4541. |

| 8. | Machado NO. Management of duodenal perforation post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. When and whom to operate and what factors determine the outcome? A review article. JOP. 2012;13:18-25. |

| 9. | Kim BS, Kim IG, Ryu BY, Kim JH, Yoo KS, Baik GH, Kim JB, Jeon JY. Management of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography-related perforations. J Korean Surg Soc. 2011;81:195-204. |

| 10. | Dubecz A, Ottmann J, Schweigert M, Stadlhuber RJ, Feith M, Wiessner V, Muschweck H, Stein HJ. Management of ERCP-related small bowel perforations: the pivotal role of physical investigation. Can J Surg. 2012;55:99-104. |

| 11. | Stapfer M, Selby RR, Stain SC, Katkhouda N, Parekh D, Jabbour N, Garry D. Management of duodenal perforation after endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography and sphincterotomy. Ann Surg. 2000;232:191-198. |

| 12. | Howard TJ, Tan T, Lehman GA, Sherman S, Madura JA, Fogel E, Swack ML, Kopecky KK. Classification and management of perforations complicating endoscopic sphincterotomy. Surgery. 1999;126:658-663; discussion 664-665. |

| 13. | Nakagawa Y, Nagai T, Soma W, Okawara H, Nakashima H, Tasaki T, Hisamatu A, Hashinaga M, Murakami K, Fujioka T. Endoscopic closure of a large ERCP-related lateral duodenal perforation by using endoloops and endoclips. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;72:216-217. |

| 14. | Manta R, Manno M, Bertani H, Barbera C, Pigò F, Mirante V, Longinotti E, Bassotti G, Conigliaro R. Endoscopic treatment of gastrointestinal fistulas using an over-the-scope clip (OTSC) device: case series from a tertiary referral center. Endoscopy. 2011;43:545-548. |

| 15. | Rábago LR, Ventosa N, Castro JL, Marco J, Herrera N, Gea F. Endoscopic treatment of postoperative fistulas resistant to conservative management using biological fibrin glue. Endoscopy. 2002;34:632-638. |

| 16. | Lippert E, Klebl FH, Schweller F, Ott C, Gelbmann CM, Schölmerich J, Endlicher E, Kullmann F. Fibrin glue in the endoscopic treatment of fistulae and anastomotic leakages of the gastrointestinal tract. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2011;26:303-311. |

| 17. | Manta R, Magno L, Conigliaro R, Caruso A, Bertani H, Manno M, Zullo A, Frazzoni M, Bassotti G, Galloro G. Endoscopic repair of post-surgical gastrointestinal complications. Dig Liver Dis. 2013;45:879-885. |

| 18. | Raju GS. Endoscopic closure of gastrointestinal leaks. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:1315-1320. |

| 19. | Tranter SE, Thompson MH. Spontaneous passage of bile duct stones: frequency of occurrence and relation to clinical presentation. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2003;85:174-177. |

| 20. | Lefemine V, Morgan RJ. Spontaneous passage of common bile duct stones in jaundiced patients. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2011;10:209-213. |