Published online May 16, 2014. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v6.i5.209

Revised: February 27, 2014

Accepted: March 11, 2014

Published online: May 16, 2014

Processing time: 171 Days and 17.4 Hours

AIM: To systematically analyze the randomized trials comparing the oncological and clinical effectiveness of laparoscopic total mesorectal excision (LTME) vs open total mesorectal excision (OTME) in the management of rectal cancer.

METHODS: Published randomized, controlled trials comparing the oncological and clinical effectiveness of LTME vs OTME in the management of rectal cancer were retrieved from the standard electronic medical databases. The data of included randomized, controlled trials was extracted and then analyzed according to the principles of meta-analysis using RevMan® statistical software. The combined outcome of the binary variables was expressed as odds ratio (OR) and the combined outcome of the continuous variables was presented in the form of standardized mean difference (SMD).

RESULTS: Data from eleven randomized, controlled trials on 2143 patients were retrieved from the electronic databases. There was a trend towards the higher risk of surgical site infection (OR = 0.66; 95%CI: 0.44-1.00; z = 1.94; P < 0.05), higher risk of incomplete total mesorectal resection (OR = 0.62; 95%CI: 0.43-0.91; z = 2.49; P < 0.01) and prolonged length of hospital stay (SMD, -1.59; 95%CI: -0.86--0.25; z = 4.22; P < 0.00001) following OTME. However, the oncological outcomes like number of harvested lymph nodes, tumour recurrence and risk of positive resection margins were statistically similar in both groups. In addition, the clinical outcomes such as operative complications, anastomotic leak and all-cause mortality were comparable between both approaches of mesorectal excision.

CONCLUSION: LTME appears to have clinically and oncologically measurable advantages over OTME in patients with primary rectal cancer in both short term and long term follow ups.

Core tip: Based upon the findings of this systematic review of eleven randomized trial on 2143 patients of rectal cancer, there is a higher risk of surgical site infection, higher risk of incomplete total mesorectal resection and prolonged length of hospital stay following open total mesorectal excision (OTME) compared to laparoscopic total mesorectal excision (LTME). The number of harvested lymph nodes, tumour recurrence and risk of positive resection margins were statistically similar in both groups. In addition, the operative complications, anastomotic leak and mortality were comparable between LTME and OTME. LTME appears to have clinically and oncologically measurable advantages over OTME in patients with primary resectable rectal cancer.

-

Citation: Sajid MS, Ahamd A, Miles WF, Baig MK. Systematic review of oncological outcomes following laparoscopic

vs open total mesorectal excision. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2014; 6(5): 209-219 - URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v6/i5/209.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v6.i5.209

Colorectal cancer is one of the major causes of mortality among western population[1,2]. Radical resection of the rectum in the form of anterior resection and abdominoperineal resection has been advocated for many decades to achieve highest level of oncological clearance and overall survival[3-8]. The introduction of total mesorectal excision in the management of rectal cancer has also enhanced survival and reduced the risk of local recurrence[9-14] because it achieves complete excision of the rectum together with its lymphatics and lymph nodes. Therefore, total mesorectal excision has become gold standard surgical strategy to treat rectal malignancies[10,11]. Laparoscopic total mesorectal excision (LTME) offers several advantages over conventional and orthodox open total mesorectal excision (OTME) such as reduced blood loss, faster recovery, reduced postoperative pain score, early feeding, early return to normal activities and a reduced risk of postoperative complications[12-16]. However, these advantages of LTME can only be availed optimally by colorectal surgeons when its oncological viability is proven on scientific grounds. One would assume that LTME for rectal cancer should offer survival and recurrence similar to OTME[17-19]. In addition, several studies have also reported the concerns towards LTME requiring longer duration of operation, needing extensive learning curve for colorectal surgeons, particularly junior colorectal trainees and cost implications of the procedure[20,21]. Aforementioned three limitations of LTME can be offset if its oncological and clinical adequacy matches the OTME. The objective of this article is to explore the oncological safety and clinical effectiveness of the LTME comparing to OTME based upon the principles of meta-analysis.

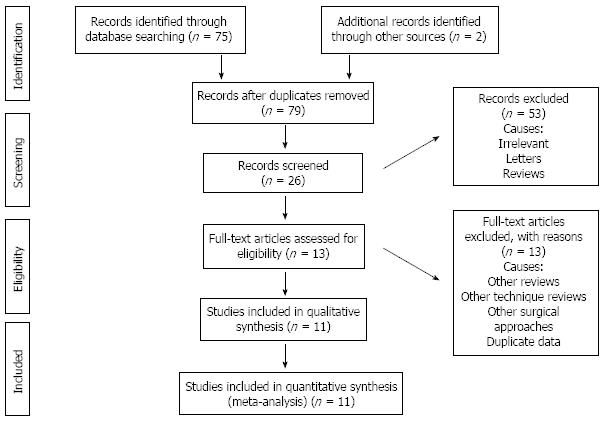

In order to obtain pertinent studies, a search of common medical electronic databases such as MEDLINE, EMBASE, and the Cochrane library for randomized, controlled trials was conducted and screened according to PRIMSA flow chart (Figure 1). The MeSH terms published in the Medline library relevant to the oncological and clinical outcomes following LTME or OTME were used to hit upon the relevant trials. No limits for language, gender, sample size and place of study origin were entered for the search in the database search engine. Boolean operators (AND, OR = NOT) were additionally used to narrow and widen the results of potentially usable studies. The titles of the published articles from the search results were examined closely and determined to be suitable for potential inclusion into this review article. The reference list from selected articles was also examined as a further search tool to discover additional trials.

For inclusion in this meta-analysis, a study had to fulfill the following criteria: (1) randomized, controlled trial; (2) comparison between LTME and OTME; (3) evaluation of a well-defined primary outcome; (4) main outcome measures reported preferably as an intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis; and (5) trials on surgical patients those have endoscopically and histologically proven rectal cancer.

Two independent reviewers using a predefined meta-analysis form abstracted relevant data of oncological and clinical outcomes following LTME and OTME from each study which resulted in high and satisfactory interobserver agreement. The extracted data contained name of the publishing authors, title of the published study, journal in which the study was published, country and year of the study, intervention protocol in the both limbs of the trial, method by which LTME and OTME was performed, testing sample size (with sex differentiation if applicable), the number of patients receiving each regimen and within the group the number of patients who succeeded and the number of patients who failed the allocated treatment, the patient compliance rate in each group, the number of patients reporting complications and the number of patients with absence of complications in each arm of the trial. After completing the data abstraction the two independent reviewers discussed the data related results and, if discrepancies were present, a consensus was reached.

The software package RevMan 5.2[22,23], provided by the Cochrane Collaboration, was used for the statistical analysis. The odds ratio (OR) with a 95%CI was calculated for binary data, and the standardized mean difference (SMD) with a 95%CI was calculated for continuous variables. The random-effects model[24,25] was used to calculate the combined outcomes of both binary and continuous variables. Heterogeneity was explored using the χ2 test, with significance set at P < 0.05, and was quantified[26] using I2, with a maximum value of 30 percent identifying low heterogeneity[26]. The Mantel-Haenszel method was used for the calculation of OR under the random effect models[27]. In a sensitivity analysis, 0.5 was added to each cell frequency for trials in which no event occurred in either the treatment or control group, according to the method recommended by Deeks et al[28]. If the standard deviation was not available, then it was calculated according to the guidelines of the Cochrane Collaboration[22]. This process involved assumptions that both groups had the same variance, which may not have been true, and variance was either estimated from the range or from the P-value. The estimate of the difference between both techniques was pooled, depending upon the effect weights in results determined by each trial estimate variance. A forest plot was used for the graphical display of the results. The square around the estimate stood for the accuracy of the estimation (sample size), and the horizontal line represented the 95%CI. The methodological quality of the randomized, controlled trials was assessed using the published guidelines of Jaddad et al[29] and Chalmers et al[30]. Based on the quality of the included randomized, controlled trials, the strength and summary of the evidence was further evaluated by GradePro®[31], a tool provided by the Cochrane Collaboration.

Incidence of complete TME was analysed as primary endpoint in this study. Secondary endpoints included circumferential resection margin (CRM) positivity, number of harvested lymph nodes, mortality, morbidity, anastomotic leak, surgical site infection and length of hospital stay.

Eleven randomized, controlled trials encompassing 2143 patients[32-42] were retrieved from the electronic databases. There were 1189 patients in the LTME group and 954 patients in the OTME group. The characteristics of the included trials are given in Table 1. The salient features and treatment protocols adopted in the included trials are given in Table 2. We used the data from one publication only from two published articles[35,36] of same randomized, controlled trial in order to avoid the duplication of data.

| Ref. | Year | Country | Age (yr) | Gender (M:F) | Follow up (mo) | Rectal cancer details | Procedure |

| Araujo et al[32] | 2003 | Brazil | Lower rectal cancer with neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy | Abdominoperineal resection | |||

| LTME | 59.1 | 9:4 | 47.2 | ||||

| OTME | 56.4 | 10:5 | 47.2 | ||||

| Baraga et al[33] | 2007 | Italy | Adenocarcinoma of the rectum suitable for resection with neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy | Anterior resection and Abdominoperineal resection | |||

| LTME | 62.8 ± 12.6 | 55:28 | 53.6 | ||||

| OTME | 65.3 ± 10.3 | 64:21 | |||||

| Gong et al[34] | 2012 | China | Lower and mid rectal adenocarcinoma without neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy | Anterior resection and Abdominoperineal resection | |||

| LTME | 58.4 ± 13.6 | 1.3:1 | 21 (9-56) | ||||

| OTME | 59.6 ± 9.4 | 1.29:1 | |||||

| Guillou et al[35] | 2005 | United Kingdom | Adenocarcinoma of left colon and rectum | Anterior resection and Abdominoperineal resection | |||

| LTME | 69 ± 11 | 44% female | 3 | ||||

| OTME | 69 ± 12 | 46% female | 3 | ||||

| Jayne et al[36] | 2007 | United Kingdom | Adenocarcinoma of left colon and rectum | Anterior resection and Abdominoperineal resection | |||

| LTME | 69 ± 11 | 44% female | 36.5 | ||||

| OTME | 69 ± 12 | 46% female | 36.5 | ||||

| Kang et al[37] | 2010 | South Korea | Lower and mid rectal adenocarcinoma with neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy | Anterior resection and Abdominoperineal resection | |||

| LTME | 57.8 ± 11.1 | 110:60 | 3 | ||||

| OTME | 59.1 ± 9.9 | 110:60 | 3 | ||||

| Lujan et al[38] | 2009 | Spain | Upper rectal adenocarcinomaMid or low rectal adenocarcinomacT3N0-2 stagePreoperative chemoradiotherapy | Anterior resection and Abdominoperineal resection | |||

| LTME | 67.8 ± 12.9 | 62:39 | 32.8 | ||||

| OTME | 66 ± 9.9 | 64:39 | 34.1 | ||||

| Ng et al[39] | 2008 | Hong Kong | Lower rectal cancer within 5 cm of the anal verge | Abdominoperineal resection | |||

| LTME | 63.7 ± 11.8 | 31:20 | 90.1 | ||||

| OTME | 63.5 ± 12.6 | 30:18 | 87.2 | ||||

| Ng et al[40] | 2009 | Hong Kong | Upper rectal adenocarcinomaPreoperative chemoradiotherapy | Anterior resection | |||

| LTME | 66.5 ± 11.9 | 37:39 | 112.5 | ||||

| OTME | 65.7 ± 12 | 48:29 | 108.8 | ||||

| Ng et al[41] | 2013 | Hong Kong | Rectal adenocarcinoma located between 5 and 12 cm from the anal verge. None of the included patient had neoadjuvant treatment | Sphincter sparing total mesorectal excision | |||

| LTME | 60.2 ± 11.3 | 24:16 | 84.6 | ||||

| OTME | 62.1 ± 12.6 | 22:18 | 92.7 | ||||

| Zhou et al[42] | 2004 | China | Low rectal adenocarcinoma Intraperitoneal and 1.5 to 8 cm from the dentate line Dukes D with local infiltration Anal sphincter sparing | Anterior resection | |||

| LTME | 26-85(44) | 43:46 | |||||

| OTME | 30-81(45) | 46:36 | 1-16 |

| Ref. | LTME group | OTME group |

| Araujo et al[32] | 4 × 10/11 mm ports were used with some variations | Procedure protocol was not reported |

| Trendelenburg position | ||

| Harmonic scalpel for dissection | ||

| Lateral to medial dissection | ||

| Endoscopic stapler for inferior mesenteric pedicle division | ||

| Colonic division by endostapler | ||

| Standard technique of colostomy construction | ||

| Standard perineal phase, dissection and closure | ||

| Baraga et al[33] | Intracorporeal vascular pedicle division, rectal mobilization and division, and anastomosis | Procedure protocol was not reported |

| Anastomosis by Knight-Griffen technique | Selective defunctioning stoma placement | |

| Selective defunctioning stoma placement | ||

| Gong et al[34] | 4 ports were used with some variations | Standard open TME |

| Medial to lateral dissection | Sphincter preserving surgery in both groups in selective patients | |

| Clips to secure inferior mesenteric pedicle | No defunctioning stoma in both groups | |

| Rectal division by endostapler | ||

| Standard technique of colostomy construction | ||

| Standard perineal phase, dissection and closure | ||

| Guillou et al[35] | Detailed procedure protocol was not reported | Detailed procedure protocol was not reported |

| Jayne et al[36] | 3 yr results of Guillou et al[35] | 3 yr results of Guillou et al[35] |

| Detailed procedure protocol was not reported | Detailed procedure protocol was not reported | |

| Kang et al[37] | Six weeks after completion of chemoradiotherapy | Detailed procedure protocol was not reported |

| 5 ports were used | Sphincter preservation in selective patients in both groups | |

| Clips to secure inferior mesenteric pedicle | ||

| Splenic flexure was mobilized in all patients | ||

| Harmonic scalpel or diathermy for dissection | ||

| Rectal division by endostapler | ||

| Colorectal anastomosis by double staple technique or by trans-anal suture | ||

| All patients had defunctioning stoma | ||

| Lujan et al[38] | 4 ports were used | Lloyd-Davis position and midline laparotomy |

| Stapled side to end colorectal or colo-anal hand sewn anastomosis | Stapled side to end colorectal or colo-anal hand sewn anastomosis | |

| Selective defunctioning stoma placement | Sphincter preservation in selective patients in both groups | |

| Selective defunctioning stoma placement | ||

| Ng et al[39] | 4 or 5 ports were used | Standard open abdominoperineal resection |

| Staplers for vascular pedicle and bowel transection | ||

| Standard perineal resection | ||

| Ng et al[40] | Protocol of the laparoscopic resection technique was not reported | Protocol of the open resection technique was not reported |

| Ng et al[41] | Lateral to medial mobilization | Protocol of the open resection technique was not reported |

| Endostapler for rectal and vascular pedicle transection | ||

| Electrocautry was used to dissect through “Holy plane” for total mesorectal resection | ||

| Splenic flexure mobilization in selective patients | ||

| Anastomosis by double stapling technique | ||

| Defunctioning stoma in selective patients | ||

| Zhou et al[42] | Lithotomy position with head down tilt | Standard open total mesorectal excision previously published by Heald et al[10,11] |

| Laparoscopy technique was not reported | Electrocautry was used for hemostasis | |

| Intracorporeal anastomosis | No defunctioning stoma | |

| Endostapler for vascular and rectal transactions | ||

| Harmonic scalpel was used for dissection | ||

| No defunctioning stoma |

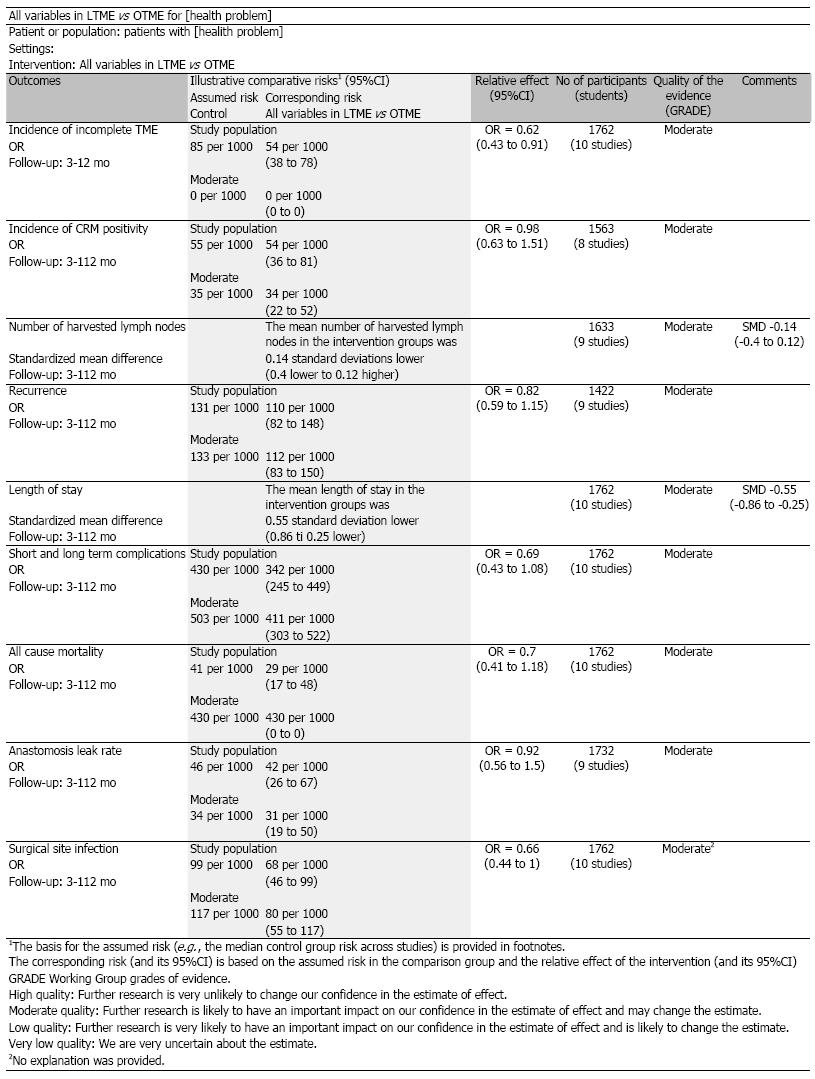

Based upon the published guidelines of Jaddad et al[29] and Chalmers et al[30] the quality of majority of included randomized, controlled trials[33,35-41] was considered good. Only three[32,34,42] included trials were scored of low quality due to the absence of adequate randomisation technique, power calculations, blinding, adequate concealment process and lack of intention-to-treat analysis. Based on the quality of included trials, the strength and summary of the evidence analyzed on GradePro®[31] is given in Figure 2. The reported quality variables of included trials are given in Table 3.

| Ref. | Randomization | Power calculations | ITT | Blinding | Concealment |

| Araujo et al[32] | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

| Baraga et al[33] | Computer generated | Yes | Yes | Yes | Sealed blinded envelops |

| Gong et al[34] | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

| Guillou et al[35] | Random allocation with 2 to 1 ratio | Yes | Yes | Not reported | Allocation communicated by telephone |

| Jayne et al[36] | Random allocation with 2 to 1 ratio | Yes | Yes | Not reported | Allocation communicated by telephone |

| Kang et al[37] | Computer generated with block permutation | Yes | Yes | Yes | Allocation communicated by telephone |

| Lujan et al[38] | Computer generated | Yes | Yes | Yes | Sealed blinded envelops |

| Ng et al[39] | Computer generated random sequence | Yes | Yes | Yes | Concealed by theatre coordinator |

| Ng et al[40] | Computer generated | Yes | Yes | Not reported | Not reported |

| Ng et al[41] | Computer generated random sequence | Yes | Yes | Yes | Concealed by theatre coordinator |

| Zhou et al[42] | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

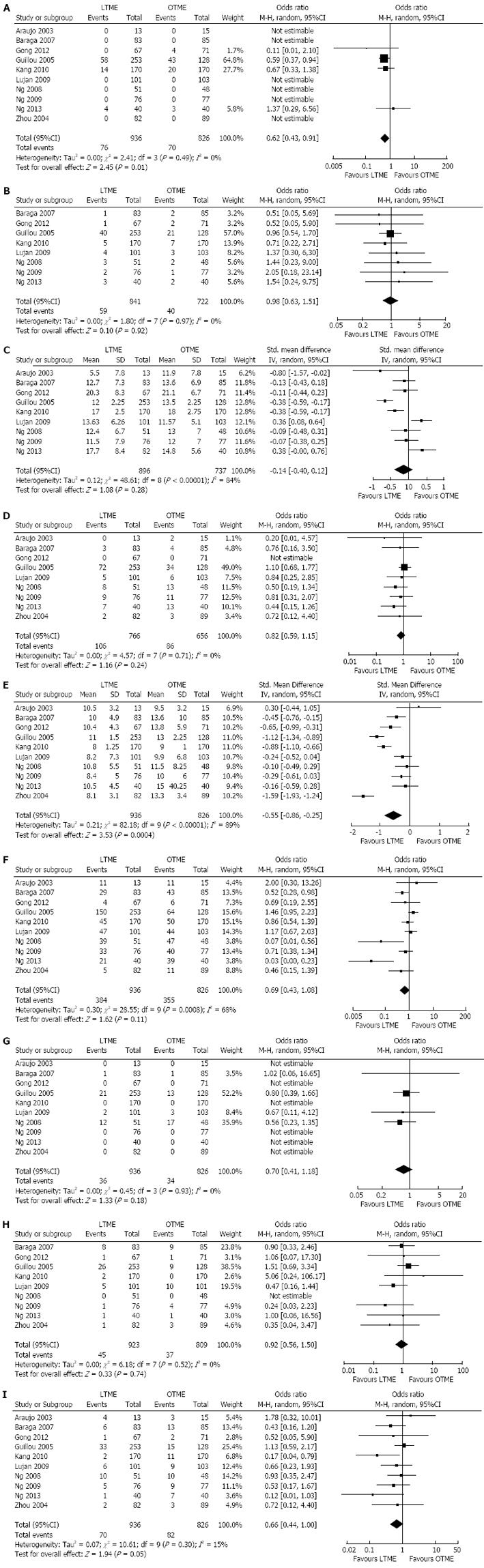

There was no heterogeneity [Tau2 = 0.00, χ2 = 2.41, γ = 3, (P = 0.49); I2 = 0%] among included studies. In the random effects model (OR = 0.62; 95%CI: 0.43-0.91; z = 2.49; P < 0.01; Figure 3A), the risk of incomplete total mesorectal excision was higher following OTME compared to LTME.

There was no heterogeneity [Tau2 = 0.0, χ2 = 1.80, γ = 7, (P = 0.97); I2 = 0%] among included studies. In the random effects model (OR = 0.98; 95%CI: 0.63, 1.51; z = 0.10; P = 0.71; Figure 3B), the risk of positive circumferential resection margins was similar following both approaches.

There was significant heterogeneity [Tau2 = 0.12, χ2 = 48.61, γ = 8, (P > 0.00001); I2 = 84%] among included studies. In the random effects model (SMD, -0.14; 95%CI: -0.40-0.12; z = 1.08; P < 0.28; Figure 3C), the number of harvested lymph nodes following both procedures was statistically similar.

There was no heterogeneity [Tau2 = 0.00, χ2 = 4.57, γ = 7, (P = 0.71); I2 = 0%] among included studies. In the random effects model (OR = 0.82; 95%CI: 0.59-1.15; z = 1.16; P = 0.24; Figure 3D), the risk of rectal cancer recurrence was similar between both types of excisions.

There was significant heterogeneity [Tau2 = 0.21, χ2 = 82.18, γ = 9, (P < 0.00001); I2 = 89%] among included studies. In the random effects model (SMD, -1.59; 95%CI: -0.86--0.25; z = 4.22; P < 0.00001; Figure 3E), the length of hospital stay was shorter following LTME compared to OTME.

There was significant heterogeneity [Tau2 = 0.30, χ2 = 28.55, γ = 9, (P < 0.0008); I2 = 68%] among included studies. In the random effects model (OR = 0.69; 95%CI: 0.43, 1.08; z = 1.62; P = 0.11; Figure 3F), the incidence of complications was similar following both approaches of rectal cancer resection.

There was no heterogeneity [Tau2 = 0.00, χ2 = 0.45, γ = 3, (P = 0.93); I2 = 0%] among included studies. In the random effects model (OR = 0.70; 95%CI: 0.41-1.18; z = 1.33; P = 0.18; Figure 3G), the incidence of overall mortality was similar following LTME and OTME.

There was no heterogeneity [Tau2 = 0.00, χ2 = 6.18, γ = 7, (P = 0.52); I2 = 0%] among included studies. In the random effects model (OR = 0.92; 95%CI: 0.56-1.50; z = 0.33; P = 0.74; Figure 3H), the risk of colorectal anastomotic dehiscence was similar following both approaches.

There was significant no heterogeneity [Tau2 = 0.07, χ2 = 10.61, γ = 9, (P = 0.30); I2 = 15%] among included studies. In the random effects model (OR = 0.66; 95%CI: 0.44-1.00; z = 1.94; P < 0.05; Figure 3I), the risk of surgical site infection was higher following OTME compared to LTME.

Based upon the findings of this largest ever systematic review of eleven randomized, controlled trial on 2143 patients of rectal cancer, there is a higher risk of surgical site infection, higher risk of incomplete total mesorectal resection and prolonged length of hospital stay following OTME compared to LTME. The oncological outcomes like the number of harvested lymph nodes, incidence of tumour recurrence and risk of positive resection margins were statistically similar in both groups. In addition, the clinical outcomes such as operative complications, anastomotic leak and all-cause mortality were comparable between both approaches of the mesorectal excision. LTME appears to have clinically and oncologically measurable advantages over OTME in patients with primary resectable rectal cancer in both short term and long term follow ups.

The findings of this article are consistent with previously published Cochrane review and a meta-analysis[43,44]. Majority of the studies in the Cochrane review[44] were non-randomized, trials and therefore the conclusion was considered weaker and biased. Similarly a recently published meta-analysis[43] failed to demonstrate the oncological safety and advantages of LTME over OTME. This review article presents a comprehensive assessment on the oncological safety of the LTME in addition to the proven clinical advantages of laparoscopy in the curative resections of rectal cancer. Proven clinical advantages of LTME have also been reported in in many published studies[32,33,35,42] which include the lesser blood loss, shorter length of hospital stay and lower postoperative pain score. In addition, the oncological adequacy of LTME has been confirmed in many recent publications[34,37,38,40].

Authors are fully aware of the fact that there are several limitations to this study. There is significant heterogeneity among included studies. Causes of heterogeneity are both clinical as well as methodological in terms of trial recruitment process. Included studies recruited patients with different stages of the rectal cancer and therefore one would expect their oncological outcome different. Combined analysis of studies on rectal cancer patients with and without neoadjuvant treatment can potentially influence the oncological outcomes which would result in biased conclusions. Variable grade and stage of the disease in recruited patients can also manipulate overall survival and risk of recurrence. Preoperative nodal disease staging by MRI scan is a standard approach and all included studies did report the use of this imaging prior to surgery. Preoperative diagnostic and staging modalities across the included trials were significantly heterogeneous and therefore can potentially be a strong source of study sample contamination leading to biased outcomes. Colorectal follow up protocol among various centres conducting these trials was significantly diverse and inconsistent. Future trials should be directed towards the involvement of major colorectal units recruiting patients of similar stage and grade of the disease with different arms evaluating outcomes with and without neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy. In addition, an agreed preoperative staging as well follow up protocol will also help to curtail the clinical and methodological flaws reported in previous trials.

Total mesorectal excision (TME) has been the gold standard treatment for the management of rectal cancer. Laparoscopic approach for TME has been reported with several advantages such as quicker recovery, reduced postoperative pain and shorter hospital stay. But the limitations compared to open approach include higher cost, longer learning curve and longer operating time.

Due to clinically measureable advantages, the laparoscopic approach may be a preferred way forward as long as oncological safety of both approaches is at least similar. Several non-randomized and randomized studies have reported the inconsistent oncological findings following laparoscopic TME and precise guidelines are still scarce. Since the introduction of new generation of laparoscopic instruments and stapling devices, the recently published studies have reported encouraging results in favour of laparoscopic TME.

This article highlights the role of laparoscopic approach for TME in current situations. This article reports the oncological safety of laparoscopic TME in terms of clear circumferential resection margins, number of harvested lymph nodes, recurrence and mortality following both open and laparoscopic TME. This article compared to other peer review publications on the same subject provides the latest and strongest evidence and may assist the colorectal surgeons in decision making.

It is an important topic, clear presentation, good readability, appropriate methods, precise results, interesting discussion, coherent tables, unambiguous conclusion. This is a very good paper.

P- Reviewers: Agarwal BB, Pan GD, Perathoner A S- Editor: Wen LL L- Editor: A E- Editor: Zhang DN

| 1. | Morris EJ, Whitehouse LE, Farrell T, Nickerson C, Thomas JD, Quirke P, Rutter MD, Rees C, Finan PJ, Wilkinson JR. A retrospective observational study examining the characteristics and outcomes of tumours diagnosed within and without of the English NHS Bowel Cancer Screening Programme. Br J Cancer. 2012;107:757-764. |

| 2. | Logan RF, Patnick J, Nickerson C, Coleman L, Rutter MD, von Wagner C. Outcomes of the Bowel Cancer Screening Programme (BCSP) in England after the first 1 million tests. Gut. 2012;61:1439-1446. |

| 3. | Vaughan-Shaw PG, Cheung T, Knight JS, Nichols PH, Pilkington SA, Mirnezami AH. A prospective case-control study of extralevator abdominoperineal excision (ELAPE) of the rectum versus conventional laparoscopic and open abdominoperineal excision: comparative analysis of short-term outcomes and quality of life. Tech Coloproctol. 2012;16:355-362. |

| 4. | Stelzner S, Hellmich G, Schubert C, Puffer E, Haroske G, Witzigmann H. Short-term outcome of extra-levator abdominoperineal excision for rectal cancer. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2011;26:919-925. |

| 5. | Mauvais F, Sabbagh C, Brehant O, Viart L, Benhaim T, Fuks D, Sinna R, Regimbeau JM. The current abdominoperineal resection: oncological problems and surgical modifications for low rectal cancer. J Visc Surg. 2011;148:e85-e93. |

| 6. | Reshef A, Lavery I, Kiran RP. Factors associated with oncologic outcomes after abdominoperineal resection compared with restorative resection for low rectal cancer: patient- and tumor-related or technical factors only? Dis Colon Rectum. 2012;55:51-58. |

| 7. | Llaguna OH, Calvo BF, Stitzenberg KB, Deal AM, Burke CT, Dixon RG, Stavas JM, Meyers MO. Utilization of interventional radiology in the postoperative management of patients after surgery for locally advanced and recurrent rectal cancer. Am Surg. 2011;77:1086-1090. |

| 8. | Araújo SE, Seid VE, Bertoncini A, Campos FG, Sousa A, Nahas SC, Cecconello I. Laparoscopic total mesorectal excision for rectal cancer after neoadjuvant treatment: targeting sphincter-preserving surgery. Hepatogastroenterology. 2011;58:1545-1554. |

| 9. | Goldberg S, Klas JV. Total mesorectal excision in the treatment of rectal cancer: a view from the USA. Semin Surg Oncol. 1998;15:87-90. |

| 10. | Heald RJ. Total mesorectal excision is optimal surgery for rectal cancer: a Scandinavian consensus. Br J Surg. 1995;82:1297-1299. |

| 11. | Heald RJ. Total mesorectal excision. Acta Chir Iugosl. 1998;45:37-38. |

| 12. | Hong D, Tabet J, Anvari M. Laparoscopic vs. open resection for colorectal adenocarcinoma. Dis Colon Rectum. 2001;44:10-8; discussion 18-9. |

| 13. | Santoro E, Carlini M, Carboni F, Feroce A. Colorectal carcinoma: laparoscopic versus traditional open surgery. A clinical trial. Hepatogastroenterology. 1999;46:900-904. |

| 14. | Braga M, Vignali A, Gianotti L, Zuliani W, Radaelli G, Gruarin P, Dellabona P, Di Carlo V. Laparoscopic versus open colorectal surgery: a randomized trial on short-term outcome. Ann Surg. 2002;236:759-66; disscussion 767. |

| 15. | Pikarsky AJ, Rosenthal R, Weiss EG, Wexner SD. Laparoscopic total mesorectal excision. Surg Endosc. 2002;16:558-562. |

| 16. | Mavrantonis C, Wexner SD, Nogueras JJ, Weiss EG, Potenti F, Pikarsky AJ. Current attitudes in laparoscopic colorectal surgery. Surg Endosc. 2002;16:1152-1157. |

| 17. | Breukink SO, Pierie JP, Grond AJ, Hoff C, Wiggers T, Meijerink WJ. Laparoscopic versus open total mesorectal excision: a case-control study. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2005;20:428-433. |

| 18. | Köckerling F, Reymond MA, Schneider C, Wittekind C, Scheidbach H, Konradt J, Köhler L, Bärlehner E, Kuthe A, Bruch HP. Prospective multicenter study of the quality of oncologic resections in patients undergoing laparoscopic colorectal surgery for cancer. The Laparoscopic Colorectal Surgery Study Group. Dis Colon Rectum. 1998;41:963-970. |

| 19. | Rullier E, Sa Cunha A, Couderc P, Rullier A, Gontier R, Saric J. Laparoscopic intersphincteric resection with coloplasty and coloanal anastomosis for mid and low rectal cancer. Br J Surg. 2003;90:445-451. |

| 20. | Weeks JC, Nelson H, Gelber S, Sargent D, Schroeder G. Short-term quality-of-life outcomes following laparoscopic-assisted colectomy vs open colectomy for colon cancer: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2002;287:321-328. |

| 21. | Cheung HY, Ng KH, Leung AL, Chung CC, Yau KK, Li MK. Laparoscopic sphincter-preserving total mesorectal excision: 10-year report. Colorectal Dis. 2011;13:627-631. |

| 22. | Higgins JPT, Green S, editors . Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Available from: http://www.cochrane-handbook.org[Accessed on 12th January 2014].. |

| 23. | Review Manager (RevMan)[Computer program]. Version 5.0. The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration: Copenhagen 2008; Available from: http://tech.cochrane.org/revman/download. |

| 24. | DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7:177-188. |

| 25. | Demets DL. Methods for combining randomized clinical trials: strengths and limitations. Stat Med. 1987;6:341-350. |

| 26. | Higgins JP, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2002;21:1539-1558. |

| 27. | Egger M, Smith GD, Altman DG. Systematic reviews in healthcare. London: BMJ Publication Group 2006; . |

| 28. | Deeks JJ, Altman DG, Bradburn MJ. Statistical methods for examining heterogeneity and combining results from several studies in meta-analysis. Systemic reviews in health care: meta-analysis in context. 2nd ed. London: BMJ Publication Group 2001; 285-312. |

| 29. | Jadad AR, Moore RA, Carroll D, Jenkinson C, Reynolds DJ, Gavaghan DJ, McQuay HJ. Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: is blinding necessary? Control Clin Trials. 1996;17:1-12. |

| 30. | Chalmers TC, Smith H, Blackburn B, Silverman B, Schroeder B, Reitman D, Ambroz A. A method for assessing the quality of a randomized control trial. Control Clin Trials. 1981;2:31-49. |

| 31. | Available from: http://ims.cochrane.org/revman/otherresources/gradepro/download. Accessed on Jan 12, 2014. |

| 32. | Araujo SE, da Silva eSousa AH, de Campos FG, Habr-Gama A, Dumarco RB, Caravatto PP, Nahas SC, da Silva J, Kiss DR, Gama-Rodrigues JJ. Conventional approach x laparoscopic abdominoperineal resection for rectal cancer treatment after neoadjuvant chemoradiation: results of a prospective randomized trial. Rev Hosp Clin Fac Med Sao Paulo. 2003;58:133-140. |

| 33. | Braga M, Frasson M, Vignali A, Zuliani W, Capretti G, Di Carlo V. Laparoscopic resection in rectal cancer patients: outcome and cost-benefit analysis. Dis Colon Rectum. 2007;50:464-471. |

| 34. | Gong J, Shi DB, Li XX, Cai SJ, Guan ZQ, Xu Y. Short-term outcomes of laparoscopic total mesorectal excision compared to open surgery. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:7308-7313. |

| 35. | Guillou PJ, Quirke P, Thorpe H, Walker J, Jayne DG, Smith AM, Heath RM, Brown JM. Short-term endpoints of conventional versus laparoscopic-assisted surgery in patients with colorectal cancer (MRC CLASICC trial): multicentre, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2005;365:1718-1726. |

| 36. | Jayne DG, Guillou PJ, Thorpe H, Quirke P, Copeland J, Smith AM, Heath RM, Brown JM. Randomized trial of laparoscopic-assisted resection of colorectal carcinoma: 3-year results of the UK MRC CLASICC Trial Group. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:3061-3068. |

| 37. | Kang SB, Park JW, Jeong SY, Nam BH, Choi HS, Kim DW, Lim SB, Lee TG, Kim DY, Kim JS. Open versus laparoscopic surgery for mid or low rectal cancer after neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy (COREAN trial): short-term outcomes of an open-label randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11:637-645. |

| 38. | Lujan J, Valero G, Hernandez Q, Sanchez A, Frutos MD, Parrilla P. Randomized clinical trial comparing laparoscopic and open surgery in patients with rectal cancer. Br J Surg. 2009;96:982-989. |

| 39. | Ng SS, Leung KL, Lee JF, Yiu RY, Li JC, Teoh AY, Leung WW. Laparoscopic-assisted versus open abdominoperineal resection for low rectal cancer: a prospective randomized trial. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15:2418-2425. |

| 40. | Ng SS, Leung KL, Lee JF, Yiu RY, Li JC, Hon SS. Long-term morbidity and oncologic outcomes of laparoscopic-assisted anterior resection for upper rectal cancer: ten-year results of a prospective, randomized trial. Dis Colon Rectum. 2009;52:558-566. |

| 41. | Ng SS, Lee JF, Yiu RY, Li JC, Hon SS, Mak TW, Ngo DK, Leung WW, Leung KL. Laparoscopic-assisted versus open total mesorectal excision with anal sphincter preservation for mid and low rectal cancer: a prospective, randomized trial. Surg Endosc. 2014;28:297-306. |

| 42. | Zhou ZG, Hu M, Li Y, Lei WZ, Yu YY, Cheng Z, Li L, Shu Y, Wang TC. Laparoscopic versus open total mesorectal excision with anal sphincter preservation for low rectal cancer. Surg Endosc. 2004;18:1211-1215. |

| 43. | Rondelli F, Trastulli S, Avenia N, Schillaci G, Cirocchi R, Gullà N, Mariani E, Bistoni G, Noya G. Is laparoscopic right colectomy more effective than open resection? A meta-analysis of randomized and nonrandomized studies. Colorectal Dis. 2012;14:e447-e469. |

| 44. | Schwenk W, Haase O, Neudecker J, Müller JM. Short term benefits for laparoscopic colorectal resection. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;CD003145. |