INTRODUCTION

The oncology field is already an important area of development for gastroenterologists[1] since diagnosis and/or treatment of early gastrointestinal neoplastic lesions is crucial for prevention and cure. Management of lesions with a low risk of lymph node metastasis usually comprises classic polypectomy and endoscopic submucosal resection (EMR). EMR has demonstrated good results dealing with esophageal, gastric, duodenal and colorectal lesions[2-5]. Ideal targets include flat lesions (Paris Classification 0-IIa and 0-IIb) less than 2 cm, although piecemeal resection is also possible with acceptable outcomes[2,6]. Endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) is a late step forward in therapeutic endoscopy for early gastrointestinal neoplasia[7] and has become a standard of care, not only in Japan where it originated in the late 1990s, but also in some other countries and regions[8-17]. ESD has also spread in its indications: gastric, esophageal, colorectal, duodenal and even hypopharyngeal early neoplasia are potential targets, with excellent results[18]. New and exciting areas of research for ESD are now being explored, like the treatment of submucosal tumors[19,20] (Figure 1).

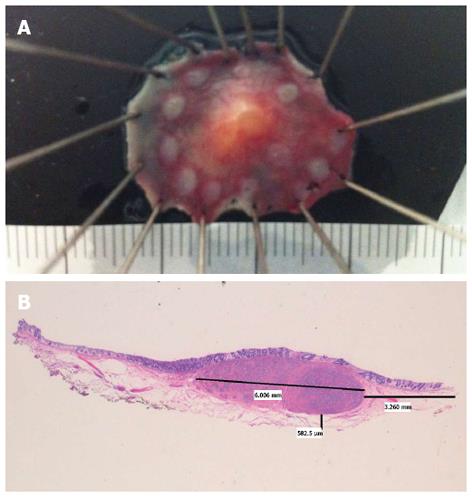

Figure 1 Rectal neuroendocrine tumor.

A: Specimen fixed after successful endoscopic submucosal dissection; B: Hematoxylin and eosin × 10. Neuroendocrine tumor, 6 mm largest diameter. Free lateral and depth margins (R0) (courtesy of Dr. Isabel Salas, Puerta de Hierro University Hospital).

The main advantages of ESD compared to EMR are a higher en bloc and R0 resection rate[21-23], with decreased local recurrence, no limitation due to size of the lesion in certain circumstances and superior pathological assessment of the cancer invasion in the specimen[24,25]. Nevertheless, ESD is associated with a higher risk of severe complications (bleeding and perforation) (Figure 2), in addition to a particularly difficult and long learning curve[21,26-28]. The latter, together with the lack of experts available for tutoring, are the most important restricting factors for a wider expansion of ESD in Western countries[11]. The lower gastric cancer incidence, with a lower proportion of early gastric cancer diagnosed during upper endoscopy procedures, also contributes to the low penetration of ESD in Western areas[13,29]. Those are the ideal cases for initial training in human ESD, as recommended by experts[9,18,30]. Unfortunately, this painful scenario for training is aggravated by the fact that many potential lesions for Western endoscopists to perform ESD are mostly found in the colon and rectum, a particularly challenging location, even for Japanese experts[31,32]. Some of the most important aspects of ESD training, with a particular section focused on colorectal ESD (CR-ESD), will be reviewed.

Figure 2 Small perforation (blue arrow) in the anterior wall of the stomach after endoscopic submucosal dissection of intramucosal adenocarcinoma (T1a, R0).

JAPANESE EXPOSURE: THE ORIGINAL SOURCE

ESD was initially developed in Japan and Japanese experts have propelled this technique to its highest standards and excellent outcomes[33,34]. In Japan, the usual way of teaching new apprentices in ESD has traditionally consisted of supervised ESD procedures by senior endoscopists in referral centers (Figure 3). This scheme seems to have worked well in recent years, but as the number of physicians performing ESD and its indications are rising, it seems that even in Japan some kind of standardized ESD training program for teaching centers is needed[35]. Most of the candidates should have demonstrated advanced skills in therapeutic upper and lower endoscopy, as well as extensive knowledge of early neoplasia endoscopic assessment. Moreover, many mentors do consider aptitudes like perseverance, competence in dealing with stressful situations and awareness of own limitations on their mentee selection process.

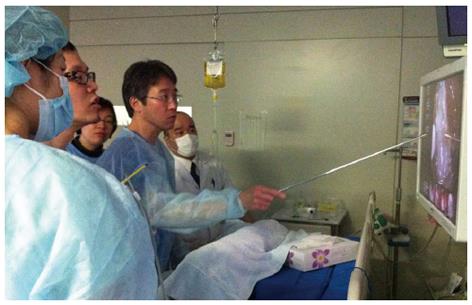

Figure 3 Professor Toyonaga supervising human endoscopic submucosal dissection case performed by young trainee.

Kobe University Hospital, Japan.

Gastric ESD is contemplated as the first step in the ESD career since the easier position and thick wall facilitates the ESD approach with a lower risk of perforation. Screening programs in gastric cancer have boosted the detection and knowledge of early gastric cancer in Japan[36]. Basic competence in terms of en bloc resection and complication rate can be reached after 30 human gastric cases have been completed under expert supervision[28,37]. Tsuji et al have described excellent results for trainees who completed 27-30 gastric ESD after having attended 40 cases and later completing 20 cases of post-ESD preventive coagulation[38]. A recent study suggests that expertise similar to well-experienced endoscopists could be achieved after having completed 80 cases, including lesions within extended criteria (ulceration, large size etc.)[39]. Some suggested the criteria for skill advances monitoring as speed, size and en bloc resection rate[28], but the location in the stomach is also a decisive factor, with more difficult cases in the body and fundus[10,39].

For many foreign physicians with an interest in ESD, Japanese teaching centers are a good opportunity for first-hand exposure in its “natural” environment[40]. They can experience how the experts perform high quality diagnostic evaluation of target lesions and perform ESD. Essential knowledge to acquire includes, but is not limited to, dye and digital chromoendoscopy, magnification endoscopy, marking and initial approach to lesions, step by step ESD procedure, tools and devices, management of minor and major complications, post-ESD surveillance and specimen fixation and pathological assessment. Overseas endoscopists are not usually allowed to do hands-on training in humans in Japan, yet they can still practice ESD in animal models with the unique opportunity of onsite expert supervision[41] (Figure 4). Furthermore, it is possible to invite Japanese experts to Western centers to get tutoring support for an initial ESD approach[42,43] (Figure 5).

Figure 4 Dr.

Morita supervising live animal endoscopic submucosal dissection case performed by trainee (Dr. Herreros de Tejada). 2nd KOBE International endoscopic submucosal dissection and EUS-FNA Hands-on-Seminar Kobe University Hospital, Japan.

Figure 5 Dr.

Morita supervising human rectal endoscopic submucosal dissection case performed by trainee (Dr. Herreros de Tejada). International endoscopic submucosal dissection Live Madrid 2013 Clinical and Hands-on Course. Puerta de Hierro University Hospital, Madrid, Spain.

In recent years, relevant progress in ESD has been observed in other neighboring countries in southeast Asia, mainly in South Korea[10,44] and China[45]. In South Korea, eligible trainees with a 2-year experience in endoscopy must observe 30-40 ESD cases to follow all steps of the procedure, including fixation of the specimen once completed; afterwards, they would serve as an assistant with knives to an expert endoscopist for 15-20 cases before being allowed to start ESD with small lesions in the antrum under close supervision[46]. As an additional reinforcement, the national Korean ESD group conducts an ex vivo hands-on course for trainees[30,47]. In the near future, we can expect high quality expert groups in Korea also offering additional opportunities for ESD training to overseas trainees.

ANIMAL TRAINING: THE WILD EXPERIENCE

Training in animal models is probably the best way to overcome some of the limitations in learning ESD[41,48]. Such a difficult technique must not be attempted in humans unless supervised by certified experts, or after an intensive animal training program has been completed and satisfactory outcomes have been achieved. The porcine model is similar to human anatomy, not expensive and widely accessible[46]. Reports of ESD in other species are scarce[16,49], including a description of a human excised portion from a sleeve gastrectomy[50]. Most studies have demonstrated the usefulness of the porcine ex vivo and in vivo for initial competence achievement in ESD, where regular endoscopes can be used and anatomic similarities in esophagus and stomach facilitates the approach[43,45,48,51,52]. The trainee can experience the early steps of the ESD process (marking, circumferential cutting and submucosal dissection), together with management of complications such as perforation and bleeding (only in vivo model). Some suggested the criteria for skill advances monitoring are speed and en bloc resection rate[53,54]. An animal training program in ESD requires appropriate settings and dedicated endoscopy equipment and materials (Figure 6), all of which is not commonly accessible to many trainees in their institutions. Some endoscopists attend special courses in ESD to get access to animal training, with good results in terms of skill improvement[43,45].

Figure 6 Operating room with equipment ready for endoscopic submucosal dissection.

Animal Research Lab. IDIPHIM. Puerta de Hierro University Hospital, Madrid, Spain.

Ex vivo model

Harvested porcine organs like esophagus and stomach are easy to set, cheap and there is no need for veterinarians or anesthesia[37,40,46]. It is not acceptable to start in the live animal before being familiarized with maneuvers and the initial steps of ESD. Perforation and associated mortality are common in live animals for those novices with no experience[45]. The freshly harvested organ should be intensively cleaned before attaching the proximal esophagus to an insertion tube inside a plastic box or placing the organ in a plastic model. A similar setting has been described for porcine harvested rectum (Figure 7), with good results for CR-ESD[55]. Although these models do not reproduce real in vivo conditions, like spontaneous motility, bleeding and tissue reaction to injection and electrocautery, the trainee can practice special maneuvers, injection, circumferential cutting and dissection. This initial phase is a good opportunity to be familiarized with different knives and devices. Insulated knives are recommended for the naïve trainee, since non-insulated knives may be associated with a higher perforation risk[45]. It is recommended that the novice should get acceptable en bloc resection and perforation-free results before stepping up to live animals[48]. The general recommendation for the trainee is to initiate ESD in porcine stomach, starting in the antrum, and then progressing according to an increasingly difficult gradation to the body, the greater curvature, the lesser curvature and the fundus[43]. Afterwards, the trainee might practice in more demanding locations like the esophagus or rectum, for which a specific ex vivo model preparation has been described elsewhere[51,55].

Figure 7 Freshly harvested porcine stomach (A) and rectum (B) attached inside a plastic box for ex vivo model.

Animal Research Lab. IDIPHIM. Puerta de Hierro University Hospital, Madrid, Spain.

In vivo model

The in vivo model is the natural and ethically accepted next step after a sufficient period of training in the ex vivo model. Using live pigs requires support from veterinarians to provide preparation of the animal (24-48 h fasting is advisable), general anesthesia and euthanasia/follow-up care of the animal after procedures are completed (Figure 8). The sense of reality increases when performing ESD in live animals, with physiological reactions, including motility, mucosal secretions, bleeding and abdominal distension. In survival studies, perforation closure outcomes and post-ESD scars can be checked, which gives a chance for practicing ESD in difficult scenarios (severe fibrosis, ulceration) afterwards. This simulation can also be set up in ex-vivo models using banding and snare transection[56], but a more realistic approach seems to be the live animal. Once the trainee has gained enough experience in the stomach, he/she could move forward to the esophagus or the rectum and colon. Whereas the former requires a similar setting to the stomach, the rectum and colon demand an intensive preparation with bowel cleaning agents and frequently additional water infusion of the rectum[40](Figure 9).

Figure 8 Gastric endoscopic submucosal dissection performed in live pig under general anesthesia.

Animal Research Lab. IDIPHIM. Puerta de Hierro University Hospital, Madrid, Spain.

Figure 9 Preparation for rectal endoscopic submucosal dissection with intensive rectal water infusion of the rectum.

Animal Research Lab. IDIPHIM. Puerta de Hierro University Hospital, Madrid, Spain.

IMPROVING YOUR SKILLS: WISE ADVICE FROM EXPERTS

There is some general advice for endoscopists already performing ESD in humans that should be kept in mind. A good field of vision and situation of the scope in relationship to the target lesion are of paramount importance. The endoscopist must know how to change the patient´s position to get the best of gravitational counter traction and a clear view to facilitate the access to the submucosal layer[57]. Managing the retroflex position accurately is particularly important when performing gastric ESD, where the fundus and body locations usually require such an approach. Getting used to dissecting while positioning in such an “inverted” fashion will demand hours of hard training, ideally in the animal model setting. It has been suggested that the appropriate level for dissection is for the depth to be beneath the vascular network and above the muscle layer, so to reduce bleeding events during ESD, as well as the risk of positive vertical margin[58]. A similar recommendation is also true for lesions with severe fibrosis and, if possible, we should try to create a nice flap starting far from the lesion border. Good quality of field of vision is paramount and experienced endoscopists recommend performing a careful and systematic hemostasis of bleeding points or, even better, appropriate preventive hemostasis of visible vessels[59]. Special care should be given to the systematic coagulation of all visible vessels in the resection site after completing the resection[58]. Animal training has been essential for introducing ESD practice in Western countries[40,42], but it also plays an important role for those endoscopists engaged in human ESD who still need to increase their skills to be able to face difficult ESD locations (colon, gastric fundus etc.). Another aspect we should bear in mind is the great importance of preserving a complete and systematic registry of all ESD cases, so that short and long term outcomes/adverse events in our series can be analyzed[11].

COLORECTAL ESD (CR-ESD): THE HIGHEST PEAK

Although gastric ESD became a standard procedure in Japan and other Asian countries a long time ago, CR-ESD is still a challenging procedure, even for Japanese experts. Most of the experience in CR-ESD comes from large studies in Japan[34,60-62]. Eligible flat colorectal lesions for ESD are increasingly diagnosed in Japan and Western countries[63-65] and will rise even more in the near future with the expansion of colorectal screening[66,67]. Absolute indications for ESD in Japan include LST-NG > 20 mm, LST-G mixed type > 40 mm and any lesion with severe fibrosis (due to EMR, biopsies or inflammatory bowel disease)[34,60,68] (Figure 10). There is controversy regarding the adoption of CR-ESD due to the high risk of failure and complications and, since EMR appears to be good enough for the management of colorectal sessile non-invasive neoplasia[2], there are advocates for exploring alternative hybrid techniques with ESD steps associated with EMR[69].

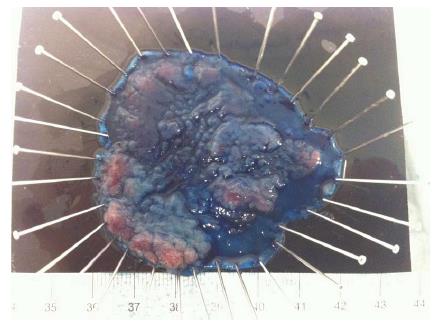

Figure 10 Colorectal-endoscopic submucosal dissection specimen fixed: LST Granular mixed type, 60 mm longest diameter located in descending colon.

Puerta de Hierro University Hospital, Madrid, Spain.

The learning curve for CR-ESD has been analyzed in several studies. Apparently, up to 80 cases might be needed to be completed before getting excellent results (en bloc and R0 resection)[70]. Sakamoto et al[71] reported a progressive learning curve by 2 supervised trainees, reaching competence level after 30 CR-ESD. Other authors have recommended a caseload of 20 or 30 gastric ESDs before attempting CR-ESD[60,72]. It is possible that this learning curve could be reduced if additional training is completed in the animal model while performing the first human cases in the rectum, where maneuverability is easier and perforation has less impact on the patient[32]. In the learning process of CR-ESD, it might be acceptable to approach smaller lesions in the rectal location (relative indication for ESD) in order to gain experience and avoid despair[27,32].

A recent European position statement in ESD recommended steps that should be taken to acquire good skills in CR-ESD: following a progressive training, mainly in animal models, and keeping a track record[11]. There are some series of CR-ESD in European centers which show inferior outcomes, slower progression and a limitation of distal locations compared to Japanese counterparts[27,73,74]. Still, results are encouraging and a recent report showed acceptable R0 and en bloc resection rates in the rectum and colon after 5 and 20 cases respectively[42]. Some Japanese experts reassure us that inexperienced Western endoscopists should not try CR-ESD in lesions with significant fibrosis or larger than 40 mm during the first 30-40 cases[32].

Selected tips for CR-ESD

Adequate positioning and a high risk of perforation are the main limitations when trying to perform successful CR-ESD. You will learn from each of your cases and you should be prepared to face complications calmly to manage them and move forward. Here is some general advice for starters from my limited personal experience: (1) Ask for proper advice from experts when planning CR-ESD. It might be very useful to send pictures and/or video clips of the lesion beforehand to an expert so that you can get recommendations of whether it is eligible for ESD, suitable or not for your level of experience, tips for the approach etc.; (2) Consider general anesthesia for CR-ESD. You may spend many hours when approaching difficult locations and regular soft breathing moves can help you get the scope stabilized and avoid unexpected bowel movements than could facilitate an unintentional perforation. Extended deep sedation with regular drugs (propofol, midazolam, pethidine etc.) might induce the patient to experience intense snoring, resulting in bowel “bouncing” that makes ESD hard enough; (3) Have some rest. When performing ESD, any minor mistake can waste all your work, so it is essential to be fresh and alert. This is not easy after some hours of tense concentration, especially in the initial period of training when CR-ESD takes so long. You should consider a break after 75-90 min of a procedure when the time of reaction and concentration level may start to decline; and (4) Do record all your procedures so you are able to review your mistakes. It is especially useful to watch those moments prior to unintentional perforation so you can learn what not to do next time. Most of the time, it is a question of an excessive push of the knife or an approach in the wrong direction.

CONCLUSION

ESD is an advanced technique for early neoplasia treatment in continuous expansion, with important advantages over EMR. However, the difficult learning curve is still the main restricting factor. Training in ESD is a long and hard journey that will require comprehensive study of the ESD essentials, attending live cases, completing an animal training program using both ex vivo and in vivo models, and finally moving on to human cases under an expert´s close supervision. For Western endoscopists, this journey will be particularly arduous, with CR-ESD as the foremost challenge. And yet, most potential candidates for ESD are and probably will be colorectal early neoplasias. Intensive preparation with all available means of training is key for actual and future trainees initiating ESD. As quoted by Prof. Toyonaga, “…ESD can be a superb treatment method that is extremely beneficial for patients when the quality is well secured…”[58]. In other words, ESD in an excellent technique and there is no substitute for excellence in ESD training.

“Never, never, never give up” - Winston Churchill.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The author would like to thank for all their mentoring and support: Drs. Toyonaga and Morita (Kobe University Hospital, Japan); Drs. Yahagi and Uraoka (Keio University Hospital, Japan); Drs. Saito and Matsuda (National Cancer Center Hospital, Japan); Dr. Parra-Blanco (Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile, Chile); Dr. Berr (Paracelsus Medical University, Austria); Drs. Tendillo and Santos (Animal Research Lab-IDIPHIM, Spain); Drs. Abreu and Calleja (Puerta de Hierro University Hospital, Spain).

P- Reviewers: Konishi K, Iizuka T, Skok P, Tsuji Y S- Editor: Wen LL L- Editor: Roemmele A E- Editor: Zhang DN