Published online Dec 16, 2014. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v6.i12.620

Revised: September 22, 2014

Accepted: October 14, 2014

Published online: December 16, 2014

Processing time: 149 Days and 0.5 Hours

Pancreatic pseudocyst formation is a well-known complication of pancreatitis. It represents about 75% of the cystic lesions of the pancreas and might be located within or surrounding the pancreatic tissue. Sixty percent of the occurrences resolve spontaneously and only persistent, symptomatic or complicated cysts need to be treated. Complications include infection, hemorrhage, gastric outlet obstruction, splenic infarction and rupture. The formation of fistulas to other viscera is rare and most commonly occurs within the stomach, duodenum or colon. We report a case of a patient with a pancreatic pseudocyst in communication with the common bile duct. There have been only few cases reported in the literature. We successfully managed our case by performing an endoscopic ultrasound-guided drainage of the pancreatic collection and a contemporaneous stenting of the common bile duct. Performed independently, both drainages are effective, safe and well-coded and the expertise on these procedures is widespread. By our knowledge this therapeutic approach was never reported in literature but we retain this is the most correct treatment for this very rare condition.

Core tip: In our opinion the combination of endoscopic ultrasound-guided drainage of the pseudocyst and the simultaneous biliary stenting represent the best endoscopic treatment. The advantages of such approach consist in a better evaluation and a more effective drainage of the cystic cavity with the possibility to collect samples for biochemical and bacteriological analysis. Furthermore, the simultaneous biliary stenting can determine, at the same time, a pressure reduction in the bile system and in the pancreatic collection facilitating the healing of the fistula.

- Citation: Crinò SF, Scalisi G, Consolo P, Varvara D, Bottari A, Pantè S, Pallio S. Novel endoscopic management for pancreatic pseudocyst with fistula to the common bile duct. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2014; 6(12): 620-624

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v6/i12/620.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v6.i12.620

Pancreatic fluid collections (PFCs) arise from disruption of a pancreatic duct, with leakage of pancreatic juice into the surrounding peripancreatic tissues, and comprise about 75% of the cystic lesions of the pancreas[1].

The revised Atlanta classification refers to collections within 4 wk of symptom onset as either acute peripancreatic fluid collections or postnecrotic pancreatic fluid collections depending upon the absence or presence of pancreatic/peripancreatic necrosis, respectively. After 4 wk of the onset of symptoms, persistent collections may gradually develop a fibrous walls and are referred to as pseudocysts (PPs) or walled-off necrosis, again depending upon the absence or presence of necrosis, respectively. In addition, these collections are further classified as sterile or infected[2].

PPs occur as a complication of acute pancreatitis in approximately 10%-20% of cases. Most of these resolve spontaneously[3] and size and duration have not been shown to be the predictors of morbidity and mortality. Expectant management even in asymptomatic large PPs has shown favorable results.

Intervention is only required in patients who develop symptoms[4] such as abdominal pain, mechanical obstruction of the gastric outlet with nausea or vomiting, jaundice for compression of the biliary system, or in whom an infection is suspected for the effective control of sepsis[5].

In recent years, it has gradually been recognized that, due to its lower morbidity rate compared to the surgical and percutaneous approaches, endoscopic treatment may be the preferred first-line approach for managing PFCs[6]. Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS)-guided drainage became the preferred method of draining PFCs which lie within 1 cm of the gastric or duodenal wall, because it presents several advantages: (1) EUS can distinguish PFCs from cystic tumors, the gallbladder and pseudoaneurysm; (2) EUS can determine the content of the PFC, such as if significant necrotic debris is present, which would then require more aggressive endoscopic approach; (3) EUS can identify interposed blood vessels and potentially reduce the risk of bleeding; and (4) EUS permits drainage of non-bulging PFCs[7].

Complications of PPs are uncommon and include sepsis, hemorrhage or pseudoaneurysm formation, rupture with pancreatic ascites, and, rarely, fistula formation to other viscera[8].

The most common sites for fistulas are between PPs and stomach, duodenum, colon and, less commonly, esophagus. Fistulas usually cause pain, inflammation, fever, septicemia, and compression of neighboring structures[9].

Fistulous communication of PPs to the common bile duct (CBD) is uncommon. It affects more frequently males, most common etiology is alcoholic chronic pancreatitis and abdominal pain is the main clinical presentation. To the best of our knowledge, there have been 17 cases reported in the literature[10-23], only three of which managed endoscopically[21-23]. We present a case of this rare condition successfully resolved performing a simultaneous, independent drainage of the PPs and the CBD, never reported in literature.

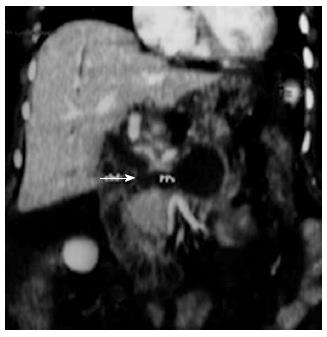

Here we describe the case of a 67-year-old Caucasian woman with history of gallstones. She didn’t refer alcohol abuse, use of drugs or history of hypertriglyceridemia. She was firstly admitted in our hospital for the onset of acute severe pancreatitis with pancreatic necrosis and acute peripancreatic fluid collection. Ranson score after 48 h was 4. She was managed conservatively and discharged after 4 wk, for the onset of concurrent nosocomial infection (pneumonia). Two weeks later, she developed progressive jaundice, upper quadrants abdominal pain and fever. Laboratory investigation revealed leukocytosis (WBC 20700) and increased indices of cholestasis. Abdominal contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) scan (Figure 1) showed in the region of the pancreatic head an 8 cm × 3 cm PPs in communication with the CBD that was dilated (12 mm) such as the intrahepatic bile ducts. Pancreatic duct was normal. Subsequently, the patient underwent endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) that revealed a long, distal biliary extrinsic compression and confirmed a fistulous communication between middle tract of the CBD and large PPs in the head of the pancreas. Biliary sphincterotomy was performed and a 10 Fr × 7 cm plastic stent was placed in the CBD.

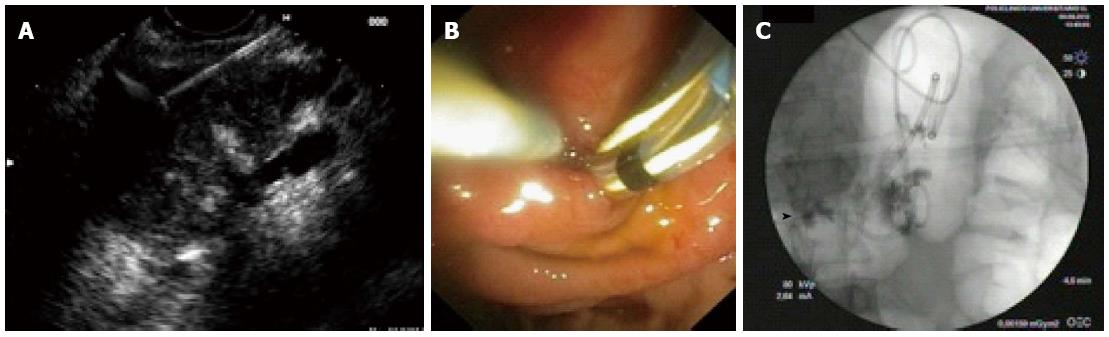

The duodenoscope was switched for an echoendoscope: at EUS the PPs resulted relatively thin-walled, with optimal contact with the gastric wall, within abundant echoic debris and encompassing both splenic vessels. Doppler assessment excluded large vessels interposition and EUS-guided drainage was performed. A 19-gauge dedicated needle (ECHO-HD-19-A, Wilson-Cook Medical Inc., Winston-Salem, North Carolina, United States) was used for the puncture of the collection (Figure 2A) and brown-purulent fluid was aspirated for bacteriological examination. A first 0.035-inch guidewire (Jagwire; Microvasive Endoscopy, Boston Scientific Corp., Natick, Massachusetts, United States) was advanced into the PPs through the inner part of the needle under fluoroscopic guidance and dilation of the fistula was obtained using a 8 mm biliary dilation balloon over the guidewire. After placing a first 10 Fr × 6 cm double pigtail plastic stent, two more 0.035-inch guidewires were placed into the collection through a catheter (Figure 2B) and a second 10 Fr double pigtail stent and a 7 Fr nasocystic catheter were then inserted (Figure 2C).

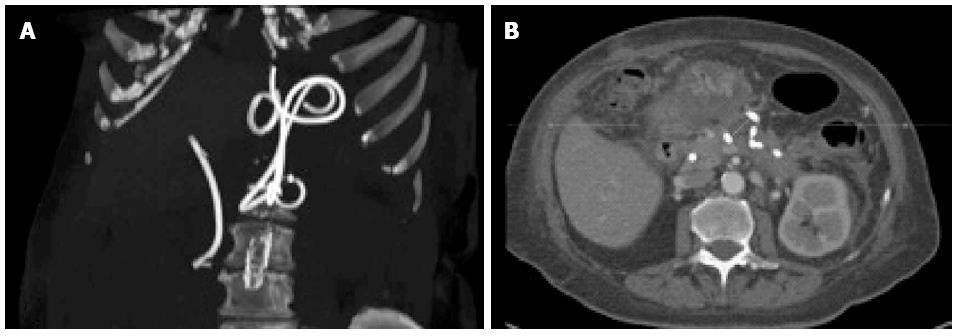

Bacterial culture from the pancreatic fluid collection resulted positive for Klebsiella Pneumonie. The patient was started on antibiotics and daily collection aspiration and washing was performed trough the nasocystic drainage. After 5 d the patient was in good clinical condition and was discharged and scheduled for the follow up. Three weeks later CT scan showed the correct position of the biliary and cystic stents (Figure 3A) and revealed a quite complete reduction of the cystic cavity (Figure 3B); the nasocystic drain was than removed.

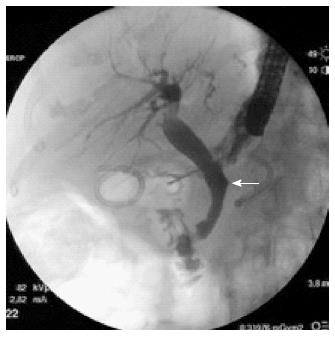

Three months later, ERCP was performed for removing the biliary stent: cholangiography revealed, after high-pressure contrast injection with a balloon catheter, the resolution of the biliary fistula (Figure 4). Both double pigtail plastic stents were leaved in place in the stomach and removed only after a further 6 mo follow up. Patient was followed for 8 mo without evidence of recurrence of the pseudocyst.

Fistulous communication of PFCs to the CBD is distinctly rare. Clinical symptoms, as in our case, are generally right upper quadrant abdominal pain, jaundice and fever.

Management of this rare condition is not defined and, in literature, only seventeen cases have been reported, ten of whom were treated surgically, three with percutaneous external drainage and one was observed. Only three cases were endoscopically managed. Carreere et al[21] treated one patient with biliopancreatic fistula with transpapillary pancreatic stenting for 5 mo.

Boulanger et al[22] reported a case of PPs with fistula to the common bile duct demonstrated at ERCP and endoscopically managed with biliary stent and, simultaneously, with a second stent placed via a transpapillary route across the fistula with one end into the pseudocyst and the other end into the duodenum. Authors don’t mention for how long both stents were leaved in place. Al Ali et al[23] performed the same endoscopic procedure. In this case, a double pigtail stent placed via the transpapillary route across the fistula into the PPs was leaved in place for 2 mo.

In our case, we successfully endoscopically managed large PPs with a fistulous communication to the CBD and within necrotic debris, by positioning a plastic biliary stent in association with simultaneous EUS-guided transgastric pancreatic collection drainage with two double pigtail stents and a nasocystic drain.

We believe that this endoscopic approach, especially in cases of very large and infected collection with necrotic debris, should be preferred to the previously described in literature for the better evaluation and the more effective drainage of the cystic cavity. Another advantage of this combined approach is that EUS provides a detailed view of the pseudocyst, the surrounding vascular structures, the anatomy of the region and can determine the content of the PFCs, such as whether it is a simple collection or if significant necrotic debris is present, which would then require a more aggressive endoscopic approach[24]. During the EUS-guided procedure is also possible to aspirate the collection content for biochemical and bacteriological analysis. For these and other reasons, EUS-guided drainage has become the standard procedure for treating symptomatic pancreatic fluid collections[25] and the expertise on this technique is widespread. The simultaneous biliary and pancreatic collection drainage determine, at the same time, a pressure reduction in the bile system and in the pancreatic collection facilitating the healing of the fistula.

In conclusion, this is the first case reported in literature of this rare condition treated with two simultaneous endoscopic procedures, both well coded and safe for the patient, resulted in a rapid healing.

A 67-year-old Caucasian woman with history of gallstones and severe acute pancreatitis was admitted to hospital for jaundice, fever and abdominal pain two wk after pancreatitis resolution.

Cholangitis, pancreatitis.

WBC 20700 and increased indices of cholestasis.

Computed tomography scan showed in the region of the pancreatic head an 8 cm x 3 cm pancreatic pseudocyst in communication with the common bile duct (CBD) that was dilated (12 mm) such as the intrahepatic bile ducts; endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) revealed a long, distal biliary extrinsic compression and confirmed a fistulous communication of the middle tract of the CBD with a large pancreatic pseudocyst in the head of the pancreas.

Biliary sphincterotomy was performed and a 10 Fr x 7 cm plastic stent was placed in the common bile duct to allow the closure of the fistula. The pseudocyst was drained by endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) and two double pigtail stents were placed between the wall of the stomach and that of pseudocysts for complete drainage.

This case describes a new endoscopic treatment obtained by combination of EUS-guided drainage of the pseudocyst and simultaneous biliary stenting. The advantages of such approach consist in a better evaluation and a more effective drainage of the cystic cavity with the possibility to collect samples for biochemical and bacteriological analysis. Furthermore biliary stenting determines pressure reduction in the bile system and in the pancreatic collection facilitating the healing of the fistula.

The authors reported a case of pancreatic pseudocyst with fistula connection with the bile duct that was successfully treated with ERCP stenting and EUS drainage.

P- Reviewer: Hu R, Teoh AYB, Voutsas V S- Editor: Tian YL L- Editor: A E- Editor: Zhang DN

| 1. | Grace PA, Williamson RC. Modern management of pancreatic pseudocysts. Br J Surg. 1993;80:573-581. |

| 2. | Thoeni RF. The revised Atlanta classification of acute pancreatitis: its importance for the radiologist and its effect on treatment. Radiology. 2012;262:751-764. |

| 3. | Bradley EL. Diagnosis and management of pancreatic pseudocysts: current concepts. Compr Ther. 1980;6:58-65. |

| 4. | Soliani P, Franzini C, Ziegler S, Del Rio P, Dell’Abate P, Piccolo D, Japichino GG, Cavestro GM, Di Mario F, Sianesi M. Pancreatic pseudocysts following acute pancreatitis: risk factors influencing therapeutic outcomes. JOP. 2004;5:338-347. |

| 5. | Singhal D, Kakodkar R, Sud R, Chaudhary A. Issues in management of pancreatic pseudocysts. JOP. 2006;7:502-507. |

| 6. | Seewald S, Ang TL, Kida M, Teng KY, Soehendra N. EUS 2008 Working Group document: evaluation of EUS-guided drainage of pancreatic-fluid collections (with video). Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;69:S13-S21. |

| 7. | Fabbri C, Luigiano C, Maimone A, Polifemo AM, Tarantino I, Cennamo V. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided drainage of pancreatic fluid collections. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;4:479-488. |

| 8. | Khanna AK, Tiwary SK, Kumar P. Pancreatic pseudocyst: therapeutic dilemma. Int J Inflam. 2012;2012:279476. |

| 9. | Clements JL, Bradley EL, Eaton SB. Spontaneous internal drainage of pancreatic pseudocysts. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1976;126:985-991. |

| 10. | Dalton WE, Lee HM, Williams GM, Hume DM. Pancreatic pseudocyst causing hemobilia and massive gastrointestinal hemorrhage. Am J Surg. 1970;120:106-107. |

| 11. | Sankaran S, Walt AJ. The natural and unnatural history of pancreatic pseudocysts. Br J Surg. 1975;62:37-44. |

| 13. | Ro JO, Yoon BH. Pancreatic pseudocyst as a cause of gastrointestinal bleeding and hemobilia. A case report. Am J Gastroenterol. 1976;66:287-291. |

| 14. | Gadacz TR, Lillemoe K, Zinner M, Merrill W. Common bile duct complications of pancreatitis evaluation and treatment. Surgery. 1983;93:235-242. |

| 15. | Skellenger ME, Patterson D, Foley NT, Jordan PH. Cholestasis due to compression of the common bile duct by pancreatic pseudocysts. Am J Surg. 1983;145:343-348. |

| 16. | Ellenbogen KA, Cameron JL, Cocco AE, Gayler BW, Hutcheon DF. Fistulous communication of a pseudocyst with the common bile duct: demonstration by endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. Johns Hopkins Med J. 1981;149:110-111. |

| 17. | DeVanna T, Dunne MG, Haney PJ. Fistulous communication of pseudocyst to the common bile duct: a complication of pancreatitis. Pediatr Radiol. 1983;13:344-345. |

| 18. | Hauptmann EM, Wojtowycz M, Reichelderfer M, McDermott JC, Crummy AB. Pancreatic pseudocyst with fistula to the common bile duct: radiological diagnosis and management. Gastrointest Radiol. 1992;17:151-153. |

| 19. | Bresler L, Vidrequin A, Poussot D, Mangin P, Pinelli G, Boissel P, Grosdidier J, Claudon M. Fistulous communication of a pancreatic pseudocyst with the common bile duct: demonstration by operative cholangiogram. Am J Gastroenterol. 1989;84:835-836. |

| 20. | Raimondo M, Ashby AM, York EA, Derfus GA, Farnell MB, Clain JE. Pancreatic pseudocyst with fistula to the common bile duct presenting with gastrointestinal bleeding. Dig Dis Sci. 1998;43:2622-2626. |

| 21. | Carrere C, Heyries L, Barthet M, Bernard JP, Grimaud JC, Sahel J. Biliopancreatic fistulas complicating pancreatic pseudocysts: a report of three cases demonstrated by endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. Endoscopy. 2001;33:91-94. |

| 22. | Boulanger S, Volpe CM, Ullah A, Lindfield V, Doerr R. Pancreatic pseudocyst with biliary fistula: treatment with endoscopic internal drainage. South Med J. 2001;94:347-349. |

| 23. | Al Ali JA, Chung H, Munk PL, Byrne MF. Pancreatic pseudocyst with fistula to the common bile duct resolved by combined biliary and pancreatic stenting--a case report and literature review. Can J Gastroenterol. 2009;23:557-559. |

| 24. | Krüger M, Schneider AS, Manns MP, Meier PN. Endoscopic management of pancreatic pseudocysts or abscesses after an EUS-guided 1-step procedure for initial access. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;63:409-416. |