Published online Jan 16, 2014. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v6.i1.20

Revised: December 4, 2013

Accepted: January 6, 2014

Published online: January 16, 2014

Processing time: 128 Days and 21.1 Hours

AIM: To investigate a new mother-baby system, consisting of a peroral cholangioscope and a duodenoscope in patients regarding its feasibility.

METHODS: In the study period from January 2007 to February 2010, 76 consecutive patients (33 men, 43 women; mean age 63 years old) were included in this pilot series. Endoluminal images and biopsies were obtained from 55 patients with indeterminate strictures, while 21 patients had fixed filling defects. The diagnostic accuracy of peroral cholangioscopy (POCS) in the visualization of strictures and tissue sampling was evaluated, and therapeutic success was monitored. Follow-up was performed over at least 9 mo.

RESULTS: A total of 55 patients had indeterminate strictures. Using the criteria “circular stenosis” and “irregular surface or margins”, POCS correctly described 27 out of 28 malignant biliary strictures and 25 out of 27 benign lesions (sensitivity, 96.4%; specificity, 92.6%, diagnostic accuracy 94.5%). Visually targeted forceps biopsies were performed in 55 patients. Tissue sampling during POCS revealed malignancy in 18 of 28 cases (sensitivity: 64.3%). In 21 patients with fixed filling defects, 10 patients with bile duct stones were successfully treated with conventional stone removal. Nine patients with difficult stones (5 giant stones and 4 intrahepatic stones) were treated with visually guided laser lithotripsy. Two patients in the group with unclear fixed filling defects had bile duct adenoma or papillary tumors and were surgically treated.

CONCLUSION: The new 95 cm POCS allows for accurate discrimination of strictures and fixed filling defects in the biliary tree, provides improved sensitivity of endoscopically guided biopsies and permits therapeutic approaches for difficult intrahepatic stones.

Core tip: A new mother-baby system, consisting of a peroral baby cholangioscope and a maternal duodenoscope, was investigated in patients regarding its feasibility. Using the criteria “circular stenosis” and “irregular surface or margins”, peroral cholangioscopy (POCS) correctly described 27 out of 28 malignant biliary strictures and 25 out of 27 benign lesions (sensitivity, 96.4%; specificity, 92.6%, diagnostic accuracy 94.5%). The new 95 cm POCS allows for accurate discrimination of strictures and fixed filling defects in the biliary tract, provides improved sensitivity of endoscopically guided biopsies and permits therapeutic approaches for difficult intrahepatic stones.

- Citation: Prinz C, Weber A, Goecke S, Neu B, Meining A, Frimberger E. A new peroral mother-baby endoscope system for biliary tract disorders. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2014; 6(1): 20-26

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v6/i1/20.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v6.i1.20

Strictures in the biliary system can lead to retention of bile, potentially resulting in jaundice, pain and fever, and are thus of great clinical importance. The differentiation between malignant and benign biliary strictures remains challenging, even with the use of transabdominal ultrasound (US), computed tomography (CT), and endoscopic retrograde cholangiography (ERC)[1]. Biliary strictures or filling defects can be caused by various inflammatory diseases, as well as by benign or malignant bile-duct tumors[2]. Malignant bile duct tumors, or so-called cholangiocarcinomas, are topographically categorized as intrahepatic or extrahepatic carcinomas[3]. Surgery is the only curative treatment for patients with cholangiocarcinoma, but the results have been more favorable for patients with early-stage disease. Therefore, a reliable diagnostic procedure is of great importance for these patients. Cholangiocarcinomas often grow longitudinally along the bile duct, rather than in a radial direction away from the bile duct. Consequently, imaging techniques, including ultrasound, CT, and magnetic resonance imaging are of limited sensitivity for the detection of cholangiocarcinoma. Therefore, biliary tissue collection during endoscopic procedures has been widely used to distinguish between benign and malignant strictures, thus providing the only definitive diagnosis that can be used to establish therapeutic strategies.

However, radiologically guided forceps biopsies, as well as brush cytology, has shown only limited sensitivity, usually approximately 40%-50%[4-6]. Furthermore, filling defects seen on ERC usually indicate the presence of bile duct stones, but these defects can also be caused by various benign or malignant tumors, including bile duct adenoma[7]. Intraductal tumors in the biliary tree can mimic large stones, and fixed filling defects that are thought to be intraductal polypoid lesions can also be stones.

Therefore, peroral cholangioscopy has been introduced to obtain visual images of the strictures, as well as visually guided biopsy[8]. Only direct endoscopic visualization of the bile duct enables a clear diagnosis of fixed filling defects and the undertaking of appropriate therapy. So far, conventional mother-baby endoscopes, such as the CHF-B20 or CHF-B30 long cholangio-pancreaticoscopes (usually longer than 160 cm), have been more demanding than the handling of short endoscopes, and thus, maneuverability inside the biliary system has been limited. In addition, the bioptic yield of the available very small biopsy forceps (outer diameter only 1 mm at the head) has been relatively poor. To overcome the aforementioned setbacks, a new, considerably shortened babyscope was developed, which allows for the insertion of a new, large-caliber biopsy forceps. The technical aspects have been presented in a separate manuscript.

The current study was designed to determine the feasibility of the new mother-baby system and to evaluate the diagnostic accuracy of a new peroral endoscope in patients with suspicious biliary strictures or fixed filling defects in the bile duct. The diagnostic accuracy of the new endoscope was consecutively evaluated in this pilot series over 2 years of continuous use in patients with unclear strictures and fixed filling defects, and patients were followed up over another 9 mo the verify their diagnoses.

The study included 76 consecutive patients (33 men, 43 women, median age 63 years old) with obstructive jaundice, dilated ducts or fixed filling defects, who were treated by endoscopic sphincterotomy followed by intraluminal endoscopy from January 2007 until February 2010 in the Department of Gastroenterology at the Technical University Munich. The patients were followed up for at least 9 mo. The study was approved by the ethical committee (Ethical Committee TUM, decision from 08-14-2006). All of the patients included in this study agreed to be interviewed according to the study protocol. Written informed consent was obtained from all of the patients before ERC, cholangioscopy with a shortened peroral cholangioscope and endoscopically guided biopsy. All of the following inclusion criteria had to be confirmed: (1) clinical diagnosis of obstructive jaundice or other evidence of biliary stenosis; (2) unclear fixed filling defects or indeterminate strictures in the biliary tree suspected by transabdominal ultrasound; or (3) forceps biopsy during cholangioscopy in patients in whom strictures were observed, and stones could be excluded.

The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Previous surgery of the liver or bile duct, except for cholecystectomy (CHE); (2) a tumor in the main duodenal papilla; (3) histologically or cytologically confirmed carcinoma before cholangioscopy; or (4) previous photodynamic therapy for patients with cholangiocarcinoma. All 76 consecutive patients undergoing peroral cholangioscopy (POCS) to confirm a diagnosis of benign or malignant lesions and to evaluate the etiology of their lesions were included in this study. By the time of cholangioscopy, all of the patients had undergone ultrasound, but only 11 of 28 patients with malignant tumors had undergone additional CT scans and/or MRCP investigations before cholangioscopy. The reason for the divergent diagnostic procedures was that most of the patients were submitted for further clarification of an indeterminate stricture or fixed filling defect, and thus, the previous diagnostic procedure varied and could not be further investigated or compared.

The new mother-baby system was developed by one of the authors (Frimberger E). ERC and endoscopic drainage were performed with a videoduodenoscope manufactured by Storz Company, in Tuttlingen, Germany. The technical details of the new mother-baby system are described in an accompanying publication in the same issue. The new babyscope was shortened by more than 1/3 the length of conventional long babyscopes. The instrumentation channel was enlarged, allowing for the insertion of large-caliber biopsy forceps with an outer diameter of the cups of 1.3 mm, which is an increase of 30% compared to conventional forceps. Corresponding to the shortness of the babyscope, the length of the forceps was shortened, thereby reducing the biopsy time considerably. The newly developed endoscopes and the large-caliber biopsy forceps were provided at no cost by Karl Storz GmbH and Co. KG, in Tuttlingen, Germany. Repairs were performed by the company without charge. There was no further financial support from any study sponsors.

During endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), sedation with propofol and midazolam was administered. Endoscopic sphincterotomy (EST) was conducted using an Olympus papillotome (Olympus, Hamburg, Germany), introduced over a Terumo guide wire. The bile duct was selectively cannulated with the peroral short cholangioscope, without using a guide wire. During cholangioscopy, the mucosal appearance of the biliary stricture was evaluated on the basis of the cholangioscopic findings; histological results were not available at this time. The procedure was performed by two physicians: one handling the mother duodenoscope, and the other handling the short peroral cholangioscope. The passage into the subsegments of the biliary system often required steering by two examiners, and therapeutic procedures particularly required the control of two examiners. The laser device was the SMART Lithognost Laser from StarMedtec, in Starnberg, Germany. The fibers were 300 μm in diameter, and the average applied intensity was 100 J. The laser distinguished stones from the bile duct and could not be activated when in contact with the bile duct wall.

The findings of malignant strictures included the following: (1) circular polypoid tissue with visible stenosis and (2) a non-homogeneous surface or irregular margins. Benign strictures included the following: (1) smooth surface mucosa, without polypoid or papillary tissue and (2) regular margins. At least two cholangioscopic images or video documentations were recorded in detail in the medical charts by the POCS operator. Endoluminal forceps biopsy was performed under endoscopic guidance. The tip of the open forceps was approximately 3 mm wide. All of the ERC, POCS and biopsy procedures were performed by experienced endoscopists, who were aware of the results of the prior ultrasound examinations, the blood parameters of cholestasis, and the previous ERC results. Forceps biopsy was performed by conventional methods via the operating channel of the POCS. Exactly 2 biopsies were obtained. The first biopsy was acquired under perfect visual control. In some cases, when post-biopsy bleeding occurred after the first biopsy, visually controlled acquisition of the biopsy was hampered due to blurred vision. In these cases, the bile duct was flushed with fluid until clear visibility was obtained, and the second biopsy was performed under visual control of the area of interest.

Pathologists received the biopsies of indeterminate bile duct strictures without knowledge of the clinical background or the endoscopic images.

For the purpose of analysis, suspicions of carcinoma and carcinoma found in biopsy specimens were considered malignant. The final diagnosis was confirmed by surgical resection, histological results, or clinical follow-up over at least 9 mo. Benign biliary lesions were confirmed by surgery (n = 2), by negative histopathologic results, and by clinical follow-up over more than 9 mo, without clinical or radiologic evidence of malignancy.

A total of 76 patients, 36 men and 40 women with a mean age of 63 years old (range 30 to 86 years), were enrolled. On the basis of ERCP findings, 55 patients were examined due to biliary strictures and 21 because of fixed filling defects in the biliary system. A side port duodenoscope was used in all of the cases. Two prototypes of the duodenoscopes were used in all of the patients without major repairs, and two cholangioscope prototypes were also used without major problems or major repairs. The short babyscope could be inserted into the biliary system in all of the cases. In particular, access to the side branches of the biliary system was easy because of the direct transmission of rotation exerted on the rear portion of the scope to its tip. Excellent transmission of shaft rotation was observed with the cholangioscope, enabling controlled passage into the intrahepatic side branches. The insertion of the 1.3 mm biopsy forceps was unproblematic and rapid, due to its considerably reduced length.

In all of the attempts, cannulation of the bile duct and POCS (n = 76) were performed successfully, without complications. The cholangioscope was easily introduced into the bile duct without the use of guide wires. Among the 55 biliary strictures, 28 were malignant, and 27 were benign. In the group with malignant cholangiocellular carcinoma (n = 24), 6 patients were surgically treated, 9 received or were enrolled for PDT treatment, and 9 patients received supportive care. Two patients in the group with benign strictures were confirmed by surgical resection (n = 2), and all of the other patients with benign strictures were monitored over at least 9 mo. The final diagnoses of the 55 patients with indeterminate strictures and 21 patients with stones are listed in Table 1.

| Type of stricture | No. | Final diagnosis | ||

| OP | Biopsy | FU | ||

| Indeterminate stricture | 55 | |||

| Malignant stricture | 28 | 5 | 15 | 8 |

| Cholangiocarcinoma | ||||

| Gallbladder cancer | ||||

| Metastasis | ||||

| Benign stricture | 27 | 2 | - | 25 |

| Inflammatory changes | ||||

| Postoperative stricture after cholecystectomy | ||||

| Biliary filling defects | 21 | 2 | - | 19 |

| Gallstones | ||||

| Bile duct adenoma (low-grade dysplasia) | ||||

| Bile duct adenoma (high-grade dysplasia) | ||||

POCS alone identified 27 out of 28 malignant strictures (sensitivity, 96.4%). One patient with metastasis of an adenocarcinoma but an unknown primary tumor seemed to have benign pathology in the POCS investigation. All of the other patients fulfilled the criteria for having circular stenosis with irregular polypoid tissue. The diagnosis of malignancy was confirmed by histology, cytology, surgical resection or clinical course.

In the patients with benign strictures, there were 2 false-positive diagnoses among 27 benign strictures, according to the results of POCS observation. Twenty-five patients were correctly described as having benign strictures. Two patients with benign stricture had strictures that appeared malignant by POCS. These patients were operated on, but no cancer was identified. The biliary system was drained with a biliary anastomosis due to the long stricture. Overall, POCS alone identified 27 of 28 malignant strictures and 25 of 27 benign strictures from mucosal appearance, and the statistical values were thus calculated as follows: sensitivity: 96.4%; specificity: 92.6%; positive predictive value: 93.1%; and negative predictive value, 96.2%.

Endobiliary forceps biopsy during peroral cholangioscopy was performed in a total of 55 patients. Two subsequent biopsies were obtained in each patient, and biopsy acquisition was thus successful in all of the investigated patients. There were no complications related to tissue sampling. Tissue sampling correctly identified 18 of 28 malignant strictures in the bile duct and all 27 benign strictures (sensitivity, 64.3%; specificity, 100%; positive predictive value, 100%; negative predictive value, 73%).

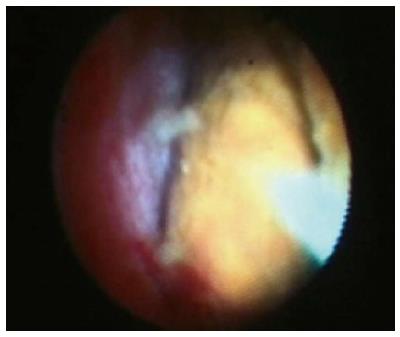

A total of 21 consecutive patients with suspected bile duct stones or unclear fixed filling defects were examined with the new cholangioscope. Detailed information regarding final diagnoses is provided in Table 1. In all 21 patients, initial ERCP with sphincterotomy was performed, and cholangioscopy was performed more than 4 d after the procedure. The cholangioscope was easily introduced into the biliary tract, including the right and left hepatic duct, in a time period shorter than 5 min. Typical features are shown in Figure 1, representing large intrahepatic stones. Nineteen patients had choledocholithiasis, and two patients had intrabiliary polyps. One patient with multiple fixed filling defects received a diagnosis of multiple bile duct adenoma with high-grade dysplasia, disseminated and continuously growing into the intrahepatic branches. One patient with a distal fixed filling defect was found to have adenoma of the bile duct, associated with a diagnosis of FAP.

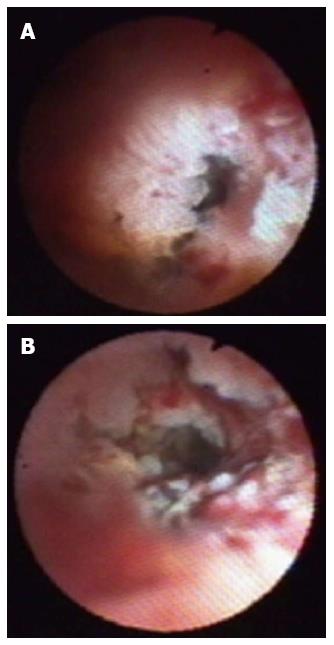

Ten patients had bile duct stones, and all of the stones could be removed with a basket or balloon. In 9 patients, cholangioscopy revealed giant bile duct stones (n = 4) or intrahepatic bile duct stones not accessible by conventional methods (n = 5) (Figure 2). These stones were treated by visually guided laser lithotripsy and were subsequently successfully removed. Most of the stones were cleared in one session. Four patients had to undergo a second POCS to remove the remaining stones and to determine the absence of further stones.

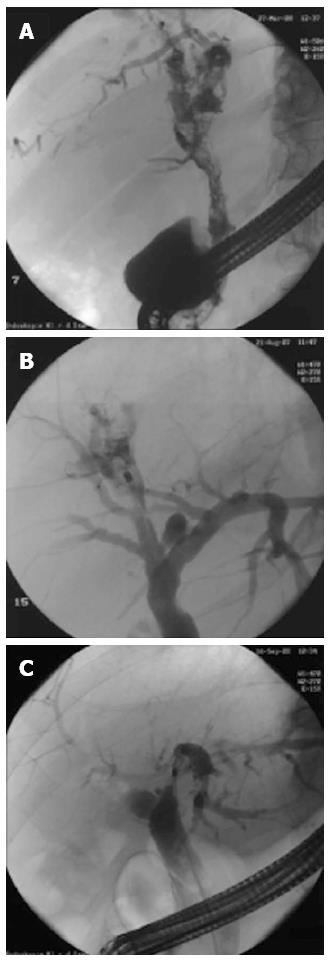

In Figure 3A, the fluoroscopic ERC image of a patient with multiple fixed filling defects can be seen. The corresponding video of the POCS shows multiple bile duct polyps of papillary and polypoid shape, and the histological evaluation revealed adenoma with high-grade intraepithelial neoplasia. From the endoluminal aspects, a papillary neoplasm similar to intraductal mucinous neoplasia of the biliary system also appeared feasible. In this patient, liver transplantation was performed successfully. In Figure 3B, the ERC of a patient with intrahepatic gall stones in liver segment S7/8 is visualized, and the corresponding video showed detection of stones, which were treated by laser lithotripsy. In Figure 3C, a patient with hilar stenosis is presented. The corresponding video showed that when the scope was withdrawn from the right hepatic duct, no tumor could be seen. The left hepatic duct showed a high-grade stenosis. The stenosis of the left hepatic duct was passed, and withdrawal was performed from the left side. The patient was operated on with a hemihepatectomy and was cured of the tumor (R0 resection).

Peroral cholangioscopy has become an important additional tool for the investigation of biliary strictures and fixed filling defects. The practicability of the new mother-baby system was monitored in 76 patients with indeterminate strictures and filling defects, which are usually true challenges for diagnostic and therapeutic endoscopy. Intubation of the biliary system with the short babyscope was possible in all of the cases, without the use of a guide wire. The excellent direct transmission of shaft rotation to the tip of the babyscope, as a consequence of the shortened shaft (redesigned for optimal torque stability), facilitated intubation of the side branches of the biliary tree, thereby allowing passage into the deeper bile duct segments. The new large-caliber biopsy forceps could be easily inserted through the instrumentation channel of the babyscope, the diameter of which was larger than the channels of conventional babyscopes.

The new technical features of the shortened baby endoscope allowed for the determination of the true nature of undetermined bile duct strictures as diagnosed in an initial ERC, to obtain additional visual information about the shape and extent of a process and to obtain histological specimens with this process. Recent studies have suggested that the sensitivity of tissue sampling via fluoroscopically guided forceps biopsy was as low as 42%[4-6]. Thus, a more sensitive and accurate differentiation of malignant and benign bile-duct diseases is essential for the planning of appropriate therapy. Because the current study did not compare blinded forceps biopsy and brush cytology with POCS biopsy, a direct comparison between radiologically vs endoscopically guided techniques could not be performed. Therefore, the sensitivity of forceps biopsy of 64% appeared to be in a similar range[4-6].

Various techniques for POCS have been used, and many types of babyscopes were developed between 1976[8] and the late 1980s[9-12]. More recent studies have confirmed that POCS is especially advantageous in the diagnosis of small mucosal biliary lesions when combined with narrow band imaging[13]. Modern POCS techniques have been further helpful in diagnosing early malignant changes in laterally spreading biliary tumor patients and in patients with persistent primary sclerosing cholangitis[14-16]. However, most of these POCS investigators used long endoscopes, with lengths greater than 160 cm, and some of the investigators complained about reduced maneuverability in small bile ducts and across strictures[11,12].

At present, the CHF-B20 and CHF-B30 systems are widely used for the diagnosis of lesions in the intrahepatic duct and the common bile duct[9-11,14-16]. Fukuda et al[17] used a variety of cholangioscopes in a large series undertaken over more than 12 years. This study reported high sensitivity in discriminating strictures from filling defects. In that study, 21 fixed filling defects of uncertain etiology were seen on ERC, but 8 of these uncertain filling defects turned out to be malignant diseases, including bile-duct cancers and cystic duct cancers. This observation is entirely in agreement with our recommendation that such unclear filling defects require further diagnostic approaches, and peroral cholangioscopy is especially suitable for this purpose. Fukuda et al[17] also reported that ERCP/tissue sampling correctly identified only 22 of 38 malignant strictures. These results are in close accordance with the data presented here, but the accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity of our technique appeared to be superior.

Recently, a new wire-guided cholangioscope, SpyGlass (Boston Scientific, Boston, MA, United States), was introduced as a new tool for cholangioscopy[18]. The SpyGlass system is a single-use, single-operator, intraductal system that allows for optical viewing and optically guided biopsies. In a recent study, Chen et al[18] reported that the rate of procedural success was 91%. Twenty patients underwent SpyGlass-directed biopsy, and the specimens procured from 19 patients (95%) were found to be adequate for histologic evaluation. The preliminary sensitivity and specificity of SpyGlass-directed biopsy to diagnose malignancy were 71% and 100%, respectively. SpyGlass-directed electrohydraulic lithotripsy succeeded in 5 of 5 patients (100%).

Also, overtube-balloon-assisted enteroscopy was recently used to place a guide wire for the positioning of an ultraslim endoscope (diameter < 6 mm) into the bile duct[19], which was considerably thicker than the babyscopes used here. The authors reported excellent feasibility and technical success in 12 of 14 patients. The use of ultraslim gastroscopes to perform choledochoscopy is, in fact, gaining popularity, and it was again reported using an overtube-balloon-assisted method for destroying large stones[20]. Because neither of the above systems was available in our center, comparative studies could not be performed.

Using the new technique with the Storz mother-baby system, we found the new shortened cholangioscope especially suitable for the evaluation and treatment of indeterminate strictures, as well as unclear filling defects. Indeterminate strictures were visually evaluated by well-defined morphological criteria: (1) circular polypoid tissue with visible stenosis; and (2) a non-homogeneous or erosive surface, with irregular margins. These criteria were chosen because bile duct cancers have previously been shown to be polypoid or papillary growing tumors associated with the formation of a stenosis[16,17]. Previous studies have found that cholangioscopy performed using two peroral cholangioscopes, the CHF-B20 (4.5 mm outer diameter) and the CHF-BP30 (3.4 mm outer diameter), typically revealed that the criteria for polypoid masses with stenosis, as well as irregular surfaces with erosions and/or ulcerations with irregular margins, were suitable for the description of 22 malignant tumors of the bile duct in 22 patients with PSC[16,17]. Using these 2 independent criteria, we found that 27 of 28 true-positive malignant tumors appeared malignant, and thus, the use of peroral cholangioscopy was highly sensitive. However, 2 of 27 patients with benign strictures also appeared malignant, and thus, over-diagnosis can result. However, it must be emphasized that such over-diagnosis can further occur with regard to the histological results obtained and interpreted after obtaining feedback. Most importantly, malignant tumors might thus not be overlooked. Also, laser lithotripsy was performed in our study through the new cholangioscope, including in 5 patients with difficult intrahepatic stones. All of the patients, especially those with intrahepatic stones, could be successfully treated, indicating that the new technique is a very useful tool, not only for diagnosis but also for the treatment of such diseases in particular.

In summary, the new peroral mother-baby endoscope system provided for easy diagnostic and therapeutic access into the common bile duct and the periphery of the biliary tract. The endoscopically chosen criteria for malignancy were adapted to previous findings and showed true-positive values in all of the cases, indicating that growth of polypoid tissue with irregular surfaces and margins is a true criterion for tumors. Vessel density on top could be additional information that is further investigated. Diagnostic and therapeutic accessories, such as large-caliber forceps or laser probes, were easily and quickly inserted through the short babyscope. Thus, the new system could become an essential tool for clinical centers focusing on biliary diseases.

We wish to thank Karl Storz GmbH and Co.KG, Tuttlingen, Germany, and Viktor Wimmer for continuing technical support.

Strictures in the biliary system can lead to retention of bile, potentially resulting in jaundice, pain and fever, and are thus of great clinical importance. The differentiation between malignant and benign biliary strictures remains challenging, even with the use of transabdominal ultrasound, computed tomography, and endoscopic retrograde cholangiography.

Therefore, peroral cholangioscopy has been introduced to obtain visual images of strictures, as well as for visually guided biopsy. Only direct endoscopic visualization of the bile duct enables a clear diagnosis of fixed filling defects and the undertaking of appropriate therapy. So far, conventional mother-baby endoscopes, such as the CHF-B20 or CHF-B30 long cholangio-pancreaticoscopes (usually longer than 160 cm), are more demanding than the handling of short endoscopes, and thus, maneuverability inside the biliary system has been limited.

Peroral cholangioscopy has become an important additional tool for the investigation of biliary strictures and fixed filling defects. The practicability of the new mother-baby system was investigated in 76 patients with indeterminate strictures and filling defects, which are usually true challenges for diagnostic and therapeutic endoscopy.

Diagnostic and therapeutic accessories, such as large-caliber forceps or laser probes, were easily and quickly inserted through the short babyscope. Thus, the new system could become an essential tool for clinical centers focusing on biliary diseases.

The new 95 cm peroral cholangioscopy allows for accurate discrimination of strictures and fixed filling defects in the biliary tract, provides improved sensitivity of endoscopically guided biopsies and permits therapeutic approaches for difficult intrahepatic stones.

P- Reviewers: Monkemuller K, Shim CS S- Editor: Ma YJ L- Editor: A E- Editor: Zhang DN

| 1. | Goldberg HI. Imaging of the biliary tract. Curr Opin Radiol. 1992;4:62-69. |

| 2. | Anderson CD, Pinson CW, Berlin J, Chari RS. Diagnosis and treatment of cholangiocarcinoma. Oncologist. 2004;9:43-57. |

| 3. | Jarnagin WR, Shoup M. Surgical management of cholangiocarcinoma. Semin Liver Dis. 2004;24:189-199. |

| 4. | Jailwala J, Fogel EL, Sherman S, Gottlieb K, Flueckiger J, Bucksot LG, Lehman GA. Triple-tissue sampling at ERCP in malignant biliary obstruction. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;51:383-390. |

| 5. | Mansfield JC, Griffin SM, Wadehra V, Matthewson K. A prospective evaluation of cytology from biliary strictures. Gut. 1997;40:671-677. |

| 6. | Weber A, von Weyhern C, Fend F, Schneider J, Neu B, Meining A, Weidenbach H, Schmid RM, Prinz C. Endoscopic transpapillary brush cytology and forceps biopsy in patients with hilar cholangiocarcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:1097-1101. |

| 7. | Fletcher ND, Wise PE, Sharp KW. Common bile duct papillary adenoma causing obstructive jaundice: case report and review of the literature. Am Surg. 2004;70:448-452. |

| 8. | Nakajima M, Akasaka Y, Fukumoto K, Mitsuyoshi Y, Kawai K. Peroral cholangiopancreatosocopy (PCPS) under duodenoscopic guidance. Am J Gastroenterol. 1976;66:241-247. |

| 9. | Bar-Meir S, Rotmensch S. A comparison between peroral choledochoscopy and endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. Gastrointest Endosc. 1987;33:13-14. |

| 10. | Kozarek RA. Direct cholangioscopy and pancreatoscopy at time of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. Am J Gastroenterol. 1988;83:55-57. |

| 11. | Riemann JF, Kohler B, Harloff M, Weber J. Peroral cholangioscopy--an improved method in the diagnosis of common bile duct diseases. Gastrointest Endosc. 1989;35:435-437. |

| 12. | Nimura Y, Kamiya J, Hayakawa N, Shionoya S. Cholangioscopic differentiation of biliary strictures and polyps. Endoscopy. 1989;21 Suppl 1:351-356. |

| 13. | Itoi T, Sofuni A, Itokawa F, Tsuchiya T, Kurihara T, Ishii K, Tsuji S, Moriyasu F, Gotoda T. Peroral cholangioscopic diagnosis of biliary-tract diseases by using narrow-band imaging (with videos). Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;66:730-736. |

| 14. | Wakai T, Shirai Y, Hatakeyama K. Peroral cholangioscopy for non-invasive papillary cholangiocarcinoma with extensive superficial ductal spread. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:6554-6556. |

| 15. | Seo DW, Lee SK, Yoo KS, Kang GH, Kim MH, Suh DJ, Min YI. Cholangioscopic findings in bile duct tumors. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;52:630-634. |

| 16. | Tischendorf JJ, Krüger M, Trautwein C, Duckstein N, Schneider A, Manns MP, Meier PN. Cholangioscopic characterization of dominant bile duct stenoses in patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis. Endoscopy. 2006;38:665-669. |

| 17. | Fukuda Y, Tsuyuguchi T, Sakai Y, Tsuchiya S, Saisyo H. Diagnostic utility of peroral cholangioscopy for various bile-duct lesions. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;62:374-382. |

| 18. | Chen YK, Pleskow DK. SpyGlass single-operator peroral cholangiopancreatoscopy system for the diagnosis and therapy of bile-duct disorders: a clinical feasibility study (with video). Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;65:832-841. |

| 19. | Choi HJ, Moon JH, Ko BM, Min SK, Song AR, Lee TH, Cheon YK, Cho YD, Park SH. Clinical feasibility of direct peroral cholangioscopy-guided photodynamic therapy for inoperable cholangiocarcinoma performed by using an ultra-slim upper endoscope (with videos). Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;73:808-813. |

| 20. | Moon JH, Ko BM, Choi HJ, Koo HC, Hong SJ, Cheon YK, Cho YD, Lee MS, Shim CS. Direct peroral cholangioscopy using an ultra-slim upper endoscope for the treatment of retained bile duct stones. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:2729-2733. |