Published online Jun 16, 2013. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v5.i6.304

Revised: April 23, 2013

Accepted: April 28, 2013

Published online: June 16, 2013

Processing time: 111 Days and 9.1 Hours

Incarceration of an endoscope in an inguinal hernia may occur during the course of routine colonoscopy. The incarceration may occur on insertion or withdrawal and frequently the hernia is not suspected prior to the colonoscopy. Most commonly, a left sided inguinal hernia is involved, however right inguinal hernias may be implicated in subjects with altered anatomy post abdominal surgery. Incarceration of an endoscope in an inguinal hernia has been seldom reported in the literature which is likely to be related to under reporting. A range of techniques have been suggested by various authors over the last four decades to manage this unusual complication of colonoscopy. These techniques include utilizing fluoroscopy, manual external pressure and/or the fitting of a cap onto the tip of the colonoscope to facilitate colonoscopic navigation. The authors present a case report of incarceration of the colonoscope on withdrawal in an unsuspected left inguinal hernia with a review of the literature on the management of this colonoscopic complication. A management strategy is suggested.

Core tip: Incarceration of a colonoscope in an inguinal hernia is likely an under reported occurrence. The authors present a case report and literature review of incarceration of a colonoscope in an inguinal hernia and a suggested management algorithm.

- Citation: Tan VPY, Lee YT, Poon JTC. Incarceration of a colonoscope in an inguinal hernia: Case report and literature review. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2013; 5(6): 304-307

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v5/i6/304.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v5.i6.304

A 76-year-old man presented for colonoscopy for follow up of previously diagnosed colonic polyps. A colonoscopy had been performed one month prior where a significant 1.2 cm sessile polyp was found in the mid transverse colon, however at that juncture given the patient’s co morbid conditions and the lack of recent clotting profile and platelet count, the decision was made to repeat the colonoscopy with polypectomy after relevant blood work was performed. During the original colonoscopy no complications were encountered and the patient did not require much sedation (midazolam 4 mg and pethidine 37.5 mg).

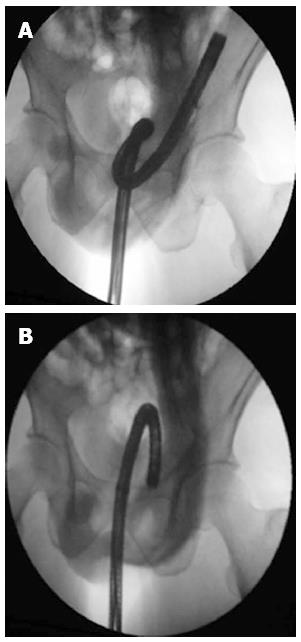

The colonoscope was inserted without difficulty or significant abdominal discomfort to the terminal ileum at 100 cm. The procedure was performed under conscious sedation and the patient had received 2 mg of midazolam and 25 mg of pethidine at this juncture. Multiple polyps in the caecum, hepatic flexure and transverse colon had been noted on insertion and were removed on with snare polypectomy on withdrawal. In the mid transverse colon at 60 cm the colonoscope could not longer be withdrawn and appeared to be “frozen” in position, although the patient did not experience significant discomfort. Despite clockwise and counter clockwise rotation with gentle traction as well as positioning the patient into the supine position the colonoscope was unable to be withdrawn. During these manoeuvres the lumen of the transverse colon could be clearly seen. An examination of the patient’s left inguinal hernia orifice revealed a bulge in the left scrotum consistent with incarceration of the colonoscope in the inguinal hernia sac (Figure 1).

The patient was given further midazolam and pethidine to a total of 5 mg and 62.5 mg, respectively, to ensure adequate analgesia and the incarcerated colonoscope was attempted to be reduced manually through external manual pressure and clockwise and counter clockwise torque with gentle traction. This was unsuccessful and the patient was immediately wheeled into the fluoroscopy suite and under direct radiographic guidance, the loop in the hernial sac was minimized and the colonoscope withdrawn by gentle traction without complication (Figure 2). The patient remained well throughout the reduction of the incarcerated colonoscope. On further withdrawal of the endoscope, a large 1-1.5 cm flat polyp was seen in the mid transverse colon which had been seen at the original endoscopy. A saline lift was attempted but the lesion did not lift the polyp which suggested sub-mucosal infiltration. Biopsies were taken, the lesion tattooed and the colonoscope withdrawn without complication. The histopathology of the lesion returned adenocarcinoma of the transverse colon. The patient was subsequently referred to the surgeons for a right hemi-colectomy and left inguinal hernia repair. An examination of the patient post colonoscopy indicated that the patient had a large sliding indirect inguinal hernia. We now present a review of the literature regarding the complication of incarceration of the colonoscope within an inguinal hernia.

Due to under reporting, the occurrence of colonoscope incarceration in an abdominal hernia is probably underestimated as evidenced by the scant number of case reports published in the English language. A total of 12 case reports involving 15 cases have been identified by the authors published to date (Table 1). The incarceration occurs both on insertion and withdrawal, usually when the endoscope is 60-80 cm from the anal verge and involves left inguinal hernias exclusively. One exception was a case published by Koltun et al[1], where the incarceration occurred in the right inguinal hernia however the patient had slightly altered abdominal anatomy due to a prior right hemi-colectomy. In only four of the cases were the presence of an inguinal hernia known prior to colonoscopy.

| Ref. | No. of cases | Inguinal hernia (side) | Method of scope removal | Distance from anus at obstruction | Obstruction on insertion vs withdrawal |

| Waye[5] | 1 | Unknown | NA | NA | NA |

| Leichtmann et al[6] | 3 | × 2 Unknown | × 2 Manual reduction | NA | NA |

| × 1 Known | × 1 Hernial reduction before and maintenance during procedure | ||||

| Fulp et al[7] | 1 | Known, | Withdrawl of endoscope | Sigmoid colon | Insertion |

| Left | |||||

| Leisser et al[8] | 1 | Unknown, Left | Manual reduction | 60 cm | Insertion |

| Koltun et al[1] | 2 | Known, | Failed fluoroscopic reduction | NA | Withdrawal |

| Right | Manual reduction utilizing “Pulley” technique | ||||

| Yamamoto et al[4] | 1 | Unknown, | Failed manual reduction, Reduction under fluoroscopic guidance | 70cm | Insertion |

| Left | |||||

| Saunder[9] | 1 | Unknown | NA | NA | NA |

| Punnam et al[10] | 1 | Known | Failed manual reduction | NA | Withdrawal |

| Left | Surgical Dissection of Hernial Sac | ||||

| Lee et al[2] | 1 | Unknown, Left | Manual reduction | NA | Insertion |

| Iser et al[11] | 1 | Unknown, | Manual reduction under deep sedation | NA | NA |

| Left | |||||

| Fan et al[3] | 1 | Unknown, | Reduction under fluoroscopy and external manual pressure | 60 cm | Withdrawal |

| Left | |||||

| Kume et al[12] | 1 | Unknown, | Reduction under fluoroscopy | 60 cm | Withdrawal |

| Left |

The neck of an indirect inguinal hernia is usually the site of obstruction when loops of bowel become incarcerated. In cases where the colonoscope becomes unable to progress on insertion, this is likely to occur due to three scenarios, firstly, a loop of bowel has become incarcerated in an inguinal hernial sac which has a small neck, the aperture of which is insufficient to permit the entry of the colonoscope[2]. In this specific scenario the hernia may only be suspected on imaging, in this case, a barium enema revealed a constriction at the level of the sigmoid colon. The second scenario occurs in patients with moderate sized inguinal hernias sufficient to permit the entry of the colonoscope into the hernial sac but not simultaneous entry and exit of the colonoscope side by side[3]. In this scenario, the tip of the colonoscope enters the hernial sac very easily but when the colonoscope forms a loop and attempts to exit the hernial sac it becomes obstructed with bulging and pain in the lower abdomen/scrotum. In the third scenario, the hernial sac is sufficiently wide enough to accommodate both the entry and exit of the two segments of colonoscope, however further insertion creates a large loop in the scrotum resulting in pain, “freezing” of the scope and inability to progress the examination[4]. For the first two scenarios, should it be necessary to proceed with the colonoscopy, use of a cap attached to the tip of the colonoscope may facilitate passage of colonoscope through the loop of bowel which has prolapsed into the hernia (unpublished data). In the third scenario, manual pressure externally may enable the colonoscopy to be completed.

However, in half of the published case studies, incarceration of the colonoscope occurs during withdrawal. Here, during the advancement phase of the colonoscope a loop forms bulging into the hernial sac. The hernial orifice is sufficiently wide to comfortably permit the entry and exit of the two segments of colonoscope, with prolapse of the colonoscope and colon into the scrotum. It is only on withdrawal of the colonoscope that a tight loop, usually a gamma loop, is formed which becomes incarcerated if the maximum diameter of the loop exceeds that of the hernial orifice, which occurred in our case.

A variety of methods have been published to reduce the incarcerated colonoscope which included manual reduction after deepened sedation, a “pulley” method of manual reduction, reduction under direct fluoroscopic guidance, surgical reduction or some combination of the aforementioned methods[1,3,4]. The authors suggest that in the event of an incarcerated colonoscope in an inguinal hernia, clinicians should proceed directly to fluoroscopic guidance if available. The benefits of fluoroscopic guidance includes the ability to minimize the colonoscope loop in the scrotal sac and an estimation of the hernial orifice to determine if removal of an incarcerate colonscope with a loop in situ is feasible. After the retraction of the loop from the scrotal sac, fluoroscopy can enable the straightening of the colonoscope before the procedure is completed[3]. Simultaneous gentle manual pressure to encourage the loop through the hernial orifice is recommended. Failing this, the authors suggest trying the “pulley” method if the hernial orifice is so small it will not permit the exit of the smallest loop feasible with the colonoscope[1]. Should this fail surgery is most likely indicated.

Some clinicians have suggested the presence of a large inguinal hernia is a relative contra-indication to colonoscopy[1]. We suggest that in the event a colonoscopy is clinically necessary prior to repair of moderate to large inguinal hernia, the option of computerized tomography colonoscopy be explored. Should a colonoscopy still be necessary, the authors suggest that the risk of incarceration may be reduced by reducing the hernia prior to colonoscopy and maintaining reduction manually whilst the scope is advanced. The use of cap assisted colonoscopy may also aid the negotiation of the endoscope through the herniated bowel loop (unpublished data). However as most of these case studies demonstrate, most cases of incarcerated colonoscopes are the first presentation of the patient with an inguinal hernia.

In summary, incarcerated colonoscopes in an inguinal hernia are, thankfully, a rare event. In patients with known inguinal hernias, consideration must be given to computed tomography colonoscopy and in the event the colonoscopy must proceed, strategies employed to reduce the risk of complication. However as our literature review has demonstrated the incarcerated scope is usually the first sign of an inguinal hernia in a patient and in this situation should be reduced under direct fluoroscopic guidance with gentle manual pressure and adequate sedation, followed by an attempt at the “pulley” system and finally, surgery, if all else fails.

P- Reviewers Girelli CM, Yoshida S S- Editor Wen LL L- Editor A E- Editor Zhang DN

| 1. | Koltun WA, Coller JA. Incarceration of colonoscope in an inguinal hernia. “Pulley” technique of removal. Dis Colon Rectum. 1991;34:191-193. |

| 3. | Fan CS, Soon MS. Colonoscope incarceration in an inguinal hernia. Endoscopy. 2007;39 Suppl 1:E185. |

| 4. | Yamamoto K, Kadakia SC. Incarceration of a colonoscope in an inguinal hernia. Gastrointest Endosc. 1994;40:396-397. |

| 5. | Waye JD. Colonoscopy: A clinical view. Mt Sinai J Med. 1975;42:1-34. |

| 6. | Leichtmann GA, Feingelrent H, Pomeranz IS, Novis BH. Colonoscopy in patients with large inguinal hernias. Gastrointest Endosc. 1991;37:494. |

| 7. | Fulp SR, Gilliam JH. Beware of the incarcerated hernia. Gastrointest Endosc. 1990;36:318-319. |

| 8. | Leisser A, Delpre G, Kadish U. Colonoscope incarceration: an avoidable event. Gastrointest Endosc. 1990;36:637-638. |

| 9. | Saunders MP. Colonoscope incarceration within an inguinal hernia: a cautionary tale. Br J Clin Pract. 1995;49:157-158. |

| 10. | Punnam SR, Ridout D. Incarcerated inguinal hernia. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;58:757-758. |

| 11. | Iser D, Ekinci E, Baichi MM, Arifuddin RM, Maliakkal BJ. Images of interest. Gastrointestinal: complications of colonoscopy. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;20:1301. |