Published online Jun 16, 2013. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v5.i6.300

Revised: April 29, 2013

Accepted: May 17, 2013

Published online: June 16, 2013

Processing time: 101 Days and 6.1 Hours

A 28-year-old woman visited our clinic with a chief complaint of epigastralgia. She had received successful Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) eradication therapy 5 years before. We repeated esophagogastroduodenoscopy, and a discolored depressed area with reddish spots and converging folds, 20 mm in size, was detected. No atrophic change including intestinal metaplasia or nodular gastritis was seen endoscopically. Two endoscopic biopsies revealed undifferentiated adenocarcinoma. No H. pylori was found, and the 13C-urea breath test was also negative. Abdominal computed tomography demonstrated no nodal involvement, distant metastasis or fluid collection. She underwent a laparoscopy-assisted distal gastrectomy. Histologically, the resected specimen revealed an early undifferentiated gastric cancer that had invaded deeply into the submucosal layer. Nodal involvement was histologically confirmed. No atrophic change or H. pylori infection was evident histologically. This is the youngest patient ever reported to have developed a node-positive early gastric cancer after eradication of H. pylori.

Core tip: Although, earlier eradication of Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) is considered to be more effective for prevention of gastric cancer by inhibiting the progression of mucosal atrophy, this youngest case developed an invasive gastric cancer with nodal involvement. From the viewpoint of the “point of no return” theory, future research should focus on the appropriate time of life at which to treat ideal candidates who would benefit from preventive eradication therapy. At present, it appears that cure of H. pylori infection still cannot prevent all gastric cancers, clinical studies are needed to clarify how to follow up patients after successful eradication therapy.

- Citation: Konuma H, Konuma I, Fu K, Yamada S, Suzuki Y, Miyazaki A. Youngest case of an early gastric cancer after successful eradication therapy. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2013; 5(6): 300-303

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v5/i6/300.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v5.i6.300

Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection plays an important role in the development of gastric cancer. Therefore, H. pylori eradication is considered an important approach for prevention of gastric cancer. H. pylori infection has been shown to induce gastric adenocarcinoma in animal models[1,2]. Furthermore, a number of studies in humans have demonstrated that H. pylori eradication has the potential to prevent gastric cancer[3-7]. Unfortunately, however, gastric cancers can still arise after H. pylori eradication therapy[8]. We herein report a case of diffuse-type early gastric cancer that developed in a young woman 5 years after successful H. pylori eradication.

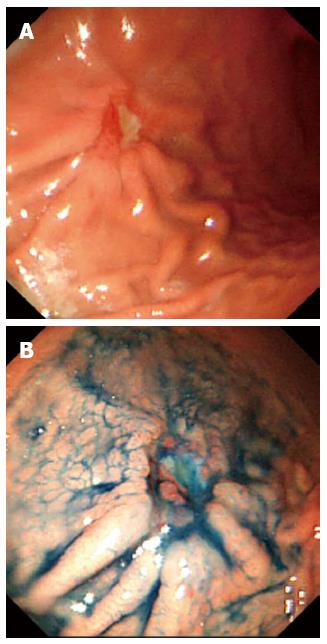

A 28-year-old woman visited our clinic with a chief complaint of epigastralgia that had lasted for 10 d. She had undergone esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) at another outpatient clinic because of epigastralgia 5 years previously. At that time, she had received successful H. pylori eradication therapy, as histologic examination of the endoscopic biopsy specimen had revealed H. pylori positivity. Her family history included a hepatocellular carcinoma in her father at the age of 31-year-old, a gastric cancer in her grandmother at the age of 67-year-old, and an esophageal squamous cell carcinoma in her grandfather at the age of 76-year-old. We repeated EGD at our clinic for further investigation, and a depressed area, 20 mm in size, was detected at the anterior wall in the greater curvature of the gastric body (Figure 1). The depressed area was discolored with a reddish spot, and converging folds were also evident endoscopically. The endoscopic diagnosis was early-stage undifferentiated adenocarcinoma (submucosal invasive carcinoma). No atrophic change including intestinal metaplasia or nodular gastritis was seen during the first and second endoscopy examinations. Two endoscopic biopsies were performed for histological evaluation, and the specimens revealed undifferentiated adenocarcinoma. However, no H. pylori was found, and the 13C-urea breath test was also negative. Abdominal computed tomography demonstrated no nodal involvement, distant metastasis or fluid collection suggestive of ascites. A final clinical diagnosis of localized early gastric cancer with undifferentiated histology was established, and the patient was sent for surgical treatment. She underwent a laparoscopy-assisted distal gastrectomy with D2 dissection of lymph nodes. Histologically, the resected specimen revealed an early undifferentiated gastric cancer that had invaded deeply into the submucosal layer, and marked lymphatic permeation (Figures 2, 3). Nodal involvement was histologically confirmed in one out of 24 dissected lymph nodes. No atrophic change or H. pylori infection was evident histologically. The pathological staging was T1bN1M0 (stage IB) according to the TNM classification. The postoperative course was uneventful, and no recurrence of gastric cancer was recognized thereafter.

To our knowledge, the present patient is the youngest ever reported to have developed a node-positive early gastric cancer after eradication of H. pylori. Until now, most reported patients developing gastric cancer after H. pylori eradication therapy have been 50 years old or more[8,9]. Characteristically, such gastric cancers have been discovered at an advanced stage significantly less frequently in Japanese patients than in patients elsewhere[8]. Most of the Japanese cases were detected at an early stage, had a depressed form, and showed an intestinal-type dominant histology[8,9]. The risk factors for gastric cancer after H. pylori eradication therapy are reportedly older age and advanced atrophic change in the gastric corpus, neither of which characterized the present case[8,10]. In the multistep pathogenesis of intestinal-type gastric cancer, H. pylori-induced chronic active gastritis slowly progresses through the premalignant stages of atrophic gastritis, intestinal metaplasia, and dysplasia to gastric adenocarcinoma. No similar sequence has been described for the diffuse type. Theoretically, H. pylori eradication stops the natural progression of premalignant lesions, and thus stabilizes the risk of gastric cancer. In the present young female patient, however, an early diffuse-type gastric cancer was detected even after H. pylori had been eradicated. The incidence of H. pylori-negative gastric cancer is extremely low (less than 1%)[10]. Recently, a prospective study reported that infection with H. pylori is associated with the development of both intestinal- and diffuse-type gastric cancer[4]. Furthermore, a close relationship between H. pylori and diffuse-type cancer has also been described, especially in younger individuals[11].

Previous reports have indicated that H. pylori eradication does not prevent the development of gastric cancer in all patients during long-term follow-up[12]. The risk of developing gastric cancer reportedly depends on the level of severity and extent of atrophic gastritis and gastric atrophy at the time of eradication. In a study from China, a beneficial effect of H. pylori eradication was seen only among those with a low baseline risk (without atrophy), and it was concluded that the chemopreventive effect of eradication is achieved during the earlier phases of carcinogenesis, before preneoplastic lesions have developed[13]. Therefore, earlier eradication of H. pylori is considered to be more effective for prevention of gastric cancer by inhibiting the progression of mucosal atrophy. Despite undergoing successful eradication therapy in her early 20s in the absence of any premalignant lesions such as mucosal atrophy or intestinal metaplasia identified endoscopically and histologically, this young woman unfortunately developed an invasive gastric cancer with nodal involvement. From the viewpoint of the “point of no return” theory (when the development of gastric cancer can no longer be prevented by H. pylori eradication), future clinical research should focus on the appropriate time of life at which to treat ideal candidates who would benefit from preventive eradication therapy. At the present time, however, it appears that cure of H. pylori infection still cannot prevent the development of gastric cancer in all patients. More data such as the optimal interval for surveillance endoscopy are needed for patients even after successful eradication of H. pylori.

P- Reviewers Kapetanos D, Rey JF S- Editor Huang XZ L- Editor A E- Editor Zhang DN

| 1. | Chen D, Stenström B, Zhao CM, Wadström T. Does Helicobacter pylori infection per se cause gastric cancer or duodenal ulcer? Inadequate evidence in Mongolian gerbils and inbred mice. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2007;50:184-189. |

| 2. | Tatematsu M, Tsukamoto T, Toyoda T. Effects of eradication of Helicobacter pylori on gastric carcinogenesis in experimental models. J Gastroenterol. 2007;42 Suppl 17:7-9. |

| 3. | Hsu PI, Lai KH, Hsu PN, Lo GH, Yu HC, Chen WC, Tsay FW, Lin HC, Tseng HH, Ger LP. Helicobacter pylori infection and the risk of gastric malignancy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:725-730. |

| 4. | Uemura N, Okamoto S, Yamamoto S, Matsumura N, Yamaguchi S, Yamakido M, Taniyama K, Sasaki N, Schlemper RJ. Helicobacter pylori infection and the development of gastric cancer. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:784-789. |

| 5. | Fuccio L, Zagari RM, Eusebi LH, Laterza L, Cennamo V, Ceroni L, Grilli D, Bazzoli F. Meta-analysis: can Helicobacter pylori eradication treatment reduce the risk for gastric cancer? Ann Intern Med. 2009;151:121-128. |

| 6. | Wu CY, Kuo KN, Wu MS, Chen YJ, Wang CB, Lin JT. Early Helicobacter pylori eradication decreases risk of gastric cancer in patients with peptic ulcer disease. Gastroenterology. 2009;137:1641-8.e1-2. |

| 7. | Ito M, Takata S, Tatsugami M, Wada Y, Imagawa S, Matsumoto Y, Takamura A, Kitamura S, Matsuo T, Tanaka S. Clinical prevention of gastric cancer by Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy: a systematic review. J Gastroenterol. 2009;44:365-371. |

| 8. | Kamada T, Hata J, Sugiu K, Kusunoki H, Ito M, Tanaka S, Inoue K, Kawamura Y, Chayama K, Haruma K. Clinical features of gastric cancer discovered after successful eradication of Helicobacter pylori: results from a 9-year prospective follow-up study in Japan. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;21:1121-1126. |

| 9. | Yamamoto K, Kato M, Takahashi M, Haneda M, Shinada K, Nishida U, Yoshida T, Sonoda N, Ono S, Nakagawa M. Clinicopathological analysis of early-stage gastric cancers detected after successful eradication of Helicobacter pylori. Helicobacter. 2011;16:210-216. |

| 10. | Matsuo T, Ito M, Takata S, Tanaka S, Yoshihara M, Chayama K. Low prevalence of Helicobacter pylori-negative gastric cancer among Japanese. Helicobacter. 2011;16:415-419. |

| 11. | Seoane A, Bessa X, Balleste B, O’Callaghan E, Panadès A, Alameda F, Navarro S, Gallén M, Andreu M, Bory F. [Helicobacter pylori and gastric cancer: relationship with histological subtype and tumor location]. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;28:60-64. |

| 12. | de Vries AC, Kuipers EJ, Rauws EA. Helicobacter pylori eradication and gastric cancer: when is the horse out of the barn? Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:1342-1345. |