Published online Jun 16, 2013. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v5.i6.288

Revised: April 24, 2013

Accepted: May 17, 2013

Published online: June 16, 2013

Processing time: 152 Days and 6.4 Hours

AIM: To determine the factors associated with the failure of stone removal by a biliary stenting strategy.

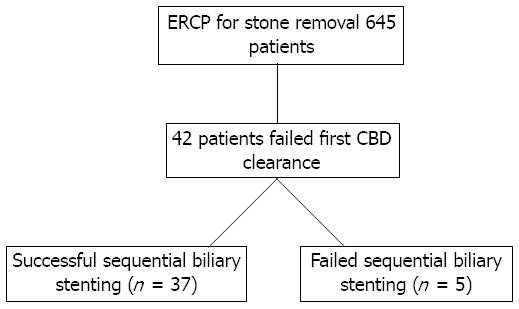

METHODS: We retrospectively reviewed 645 patients with common bile duct (CBD) stones who underwent endoscopic retrograde cholangiography for stone removal in Siriraj GI Endoscopy center, Siriraj Hospital from June 2009 to June 2012. A total of 42 patients with unsuccessful initial removal of large CBD stones that underwent sequential biliary stenting were enrolled in the present study. The demographic data, laboratory results, stone characteristics, procedure details, and clinical outcomes were recorded and analyzed. In addition, the patients were classified into two groups based on outcome, successful or failed sequential biliary stenting, and the above factors were compared.

RESULTS: Among the initial 42 patients with unsuccessful initial removal of large CBD stones, there were 37 successful biliary stenting cases and five failed cases. Complete CBD clearance was achieved in 88.0% of cases. The average number of sessions needed before complete stone removal was achieved was 2.43 at an average of 25 wk after the first procedure. Complications during the follow-up period occurred in 19.1% of cases, comprising ascending cholangitis (14.3%) and pancreatitis (4.8%). The factors associated with failure of complete CBD stone clearance in the biliary stenting group were unchanged CBD stone size after the first biliary stenting attempt (10.2 wk) and a greater number of endoscopic retrograde cholangio-pancreatography sessions performed (4.2 sessions).

CONCLUSION: The sequential biliary stenting is an effective management strategy for the failure of initial large CBD stone removal.

Core tip: This study was a retrospective review of 42 patients who underwent sequential biliary stenting following a failed removal of a large common bile duct stone by endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. Complete common bile duct (CBD) clearance was achieved in 88% of the patients at 25 wk after the first procedure, while 19% reported complications. The common complications were cholangitis and pancreatitis. The factors associated with the failure of this strategy were unchanged CBD stone size at the second biliary stenting attempt, and more endoscopic retrograde cholangio-pancreatography sessions performed.

- Citation: Prachayakul V, Aswakul P. Failure of sequential biliary stenting for unsuccessful common bile duct stone removal. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2013; 5(6): 288-292

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v5/i6/288.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v5.i6.288

Patients with untreated common bile duct (CBD) stones, irrespective of the presence of symptoms, are at high risk of experiencing further symptoms or complications. Given the potentially serious complications of CBD stones such as ascending cholangitis or acute pancreatitis, specific therapy is usually required[1]. Choledocholithiasis is one of the most common indications for performing therapeutic endoscopic retrograde cholangiography (ERC)[1].

The majority (80%-90%) of simple CBD stones, specifically those that are < 1 cm, are removed by ERC via endoscopic sphincterotomy by using a basket or balloon catheter[2,3]. However, from references[4-15], we know that approximately 10%-15% of patients have bile duct stones that cannot be removed using standard techniques. These stones are generally larger than 1-1.5 cm, impacted, located proximal to strictures, or associated with the duodenal diverticulum, and are frequently successfully removed by mechanical lithotripsy or large balloon sphincteroplasty[16]. However, the removal of large CBD stones is not possible by using these techniques. Therefore, most endoscopists prefer to place a biliary stent as a temporary measure to maintain biliary drainage and prevent stone impaction[17]. Biliary stenting is an effective method of reducing the size of CBD stones because the stone-stent friction force can lead to stone fragmentation inside the CBD[18,19]. Therefore, sequential biliary stenting is still the most common technique for large CBD stone removal. However, this technique can be time-consuming for complete stone removal and is associated with a higher complication rate during the follow-up period, particularly from cholangitis. Thorough studies examining the success factors for this treatments strategy are incomplete or lacking[18-20]. Thus, the aim of this study was to determine the factors that can potentially predict a high failure rate of the first CBD clearance, in turn providing a clearer picture of patients who can be managed conservatively by sequential biliary stenting.

The medical records and endoscopic reports of patients who underwent ERC for choledocholithiasis from June 2009 to June 2012 were retrospectively reviewed (645 total records). The siriraj institutional review board gave approval for the study. Experienced endoscopists or gastroenterology fellows under the supervision of experienced endoscopists performed all ERC procedures. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) large CBD stones (diameter of > 15 mm); (2) failure of complete stone removal during the initial attempt and biliary stent insertion; and (3) follow-up and subsequent ERC procedures performed in our institution. Patients were classified into two groups: group one comprised patients who underwent repeated short-term biliary stenting after failure of CBD clearance (with standard techniques or mechanical lithotripsy or balloon sphincteroplasty) until achievement of complete CBD clearance; group two comprised patients who underwent failed biliary stenting. Patients who were unable to be contacted for a follow-up or who did not undergo further procedures in our institute were excluded. The study design is presented in Figure 1. Five dedicated endoscopists, each performing more than 200 cases annually, performed the ERC procedures with biliary stenting. We used a therapeutic duodenoscope (Olympus TJF-140 or TJF-160; Olympus America, Central Valley, PA, United States) with patients under intravenous sedation or general anesthesia with full anesthetic monitoring. Patients with ascending cholangitis received pre-procedural antibiotics. The first treatment attempt was standard endoscopic sphincterotomy, stone retrieval via balloon retrieval catheter or basket extraction catheter, and crushing by mechanical lithotripsy (Soehendra Lithotriptor; Wilson-Cook Medical Inc., Winston-Salem, NC, United States) at the discretion of the endoscopists. After the initial clearance attempts failed, patients underwent biliary stenting and were scheduled for repeated ERC. Straight plastic stents (Cotton-Leung Biliary Endoprosthesis; Wilson-Cook Medical Inc., United States) or double pigtail plastic stents (C-flex Biliary; Boston Scientific, Spencer, IN, United States) were used. The clearance of the biliary tract was documented using a cholangiogram. The success of biliary clearance, cost of the procedures, degree of complications, time interval between the initial attempt and complete CBD clearance of the stones, surgical procedures, and complications during follow-up were assessed. The follow-up period extended to the last recorded medical visit. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize patients’ baseline demographics, clinical characteristics, and radiographic data. Continuous variables were reported as means or medians (min, max).

The compared data were analyzed using a χ2 or Mann-Whitney U test. A value of P < 0.05 was considered significant. All statistical evaluations were performed using SPSS version 11.5 software.

A total of 645 medical records and electronic endoscopy records were retrospectively reviewed, and 42 patients who met the inclusion criteria were enrolled in the study. Thirty-seven patients achieved successful sequential biliary stenting after the failure of initial stone extraction, whereas this strategy failed in five patients. Of the 42 patients were enrolled, 81% were women, and the mean age was 71.9 ± 14.2 years (range: 33-97 years). Almost 90% of patients were symptomatic, presenting with ascending cholangitis, biliary pain, obstructive jaundice, or acute pancreatitis (52.4%, 23.8%, 9.5%, and 4.8%, respectively). The stones were located at the distal, middle, and proximal portions of the CBD in 47.6%, 47.6%, and 4.8% of cases, respectively. Eight-eight percent were fit to the duct. The mean number of stones per patient was 1.5 ± 1.1 stones (range: 1-6 stones), the mean stone maximum diameter was 1.86 ± 0.43 cm (range: 1.5-3.0 cm), and the average CBD maximum diameter was 1.83 ± 0.45 cm (range: 1.2-3.5 cm). Patients who underwent biliary stenting were followed for an average of 12.8 mo (range: 2-54 mo) after the initial stone removal attempt. Biliary clearance was achieved in 88.0% of cases, with an average time between each attempt of 10.2 wk (range: 5-24 wk), and an average time to complete duct clearance of 26.8 wk (range: 6-216 wk). The average number of sessions for complete biliary clearance was 2.5 ± 0.86 procedures (range: 2-6 procedures). The baseline characteristics of the patients and procedural details (including cholangiographic findings) are shown in Table 1.

| Details | Total (n = 42) | Success group(n = 37) | Failed group(n = 5) | P value |

| Male sex | 34 (81.0) | 6 (16.2) | 2 (40.0) | NS |

| Age in years | 71.9 ± 14.2 | 71.9 ± 14.3 | 72.0 ± 15.5 | NS |

| Indications for ERC | ||||

| Cholangitis | 22 (52.4) | 20 (54.1) | 2 (40.0) | NS |

| Biliary pain | 10 (23.8) | 8 (21.6) | 2 (40.0) | |

| Obstructive jaundice | 4 (9.5) | 3 (8.1) | 1 (20.0) | |

| Acute pancreatitis | 2 (4.8) | 2 (5.4) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Asymptomatic | 4 (9.5) | 4 (9.5) | 0 (0.0) | |

| CBD size in mm | 1.83 ± 0.45 | 1.80 ± 0.44 | 2.06 ± 0.56 | NS |

| Stone size in mm | 1.86 ± 0.43 | 1.85 ± 0.41 | 2.04 ± 0.58 | NS |

| Stone number | 1.50 ± 1.06 | 1.51 ± 1.12 | 1.40 ± 0.55 | NS |

| Stone fit to CBD | 37 (88.1) | 32 (86.5) | 5 (100) | NS |

| Stone shape | NS | |||

| Irregular | 7 (18.9) | 1 (20.0) | ||

| Geometric (oval, cube) | 30 (81.1) | 4 (80.0) | ||

| Stone characteristics | NS | |||

| Mixed stone | 17 (45.9) | 3 (60.0) | ||

| Cholesterol stone | 20 (54.1) | 2 (40.0) | ||

| Change in stone size | ||||

| Decrease | 25 (67.6) | 1 (20.0) | 0.04 | |

| Stable | 12 (32.4) | 4 (80.0) | ||

| Balloon sphincteroplasty | 9 (24.3) | 3 (60.0) | 0.13 | |

| Use of mechanical lithotripsy | 14 (37.8) | 2 (40.0) | NS | |

| Time to successful procedures in weeks | 25.42 ± 40.42 | None | NA | |

| Sessions carried out | 2.43 ± 0.80 | 2.80 ± 1.30 | NS | |

| Average follow-up time in months | 13.10 ± 13.79 | 10.70 ± 8.81 | NS | |

| Complications during follow-up period | NS | |||

| Ascending cholangitis | 6 (14.3) | 6 (16.2) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Acute pancreatitis | 2 (4.8) | 1 (2.7) | 1 (20.0) | |

| None | 34 (80.9) | 30 (81.1) | 4 (80.0) |

Table 1 compares the clinical characteristics, cholangiographic features, and procedure details between the two groups of patients. Stone shape, size, and characteristics were similar between the groups. For patients with failed sequential biliary stenting, the average time interval after the first endoscopic retrograde cholangio-pancreatography (ERCP) to surgery was 71 wk (range: 28-184 wk), and the average number of sessions performed before surgery was 4.2 sessions (range: 3-6 sessions). The surgical outcomes were satisfactory without significant complications. The patients who underwent successful sequential biliary stenting had an average time interval between the first attempt and complete CBD clearance of 25.4 wk (range: 6-216 wk), and the average number of sessions performed was 2.43 sessions (range: 2-6 sessions). The factors that may be related to the failure of sequential biliary stenting were no reduction of CBD stone size at the second procedure (P = 0.04) and a greater number of sessions performed (P < 0.001). Another factor that may contribute to the failure of sequential biliary stenting, albeit insignificant in our study (P = 0.13), is the failure of balloon sphincteroplasty at the first attempt. A study in a larger cohort may be required to confirm this result.

Almost 7% of the patients in this study had large CBD stones that were not completely cleared using standard techniques at the first attempt, which is consistent with reports from other endoscopy centers[1-3,16,17]. Almost 90% of all patients in this study were symptomatic, and the most common clinical presentation was ascending cholangitis. Stones were located throughout the CBD, but more prominently in the distal and mid portions. The conventional management of large CBD stones that fail to be completely removed at the first attempt is sequential biliary stenting, which reduces stone size by stent-stone friction force. We observed that leaving the stent inside the CBD for an average of 10 wk resulted in stone size reduction in 45% of the cases and complete disappearance in 16% of the enrolled patients. Furthermore, we speculated that the CBD might have been completely cleared in 85.7% of patients by further serial sessions combined with the use of mechanical lithotripsy. Nineteen percent of patients suffered from complications during the follow-up period, which were primarily related to ascending cholangitis. Chan et al[20] reported on a total of 46 patients with large CBD stones who were treated with plastic stent insertion, among which 28 cases underwent repeated ERC. Stones were extracted after a median of 63 d, and the repeated procedures achieved complete duct clearance in 25 (89%) of the patients. Similar results have also been reported by Maxton et al[21] and Jain et al[22]. The most common complications we observed were cholangitis and pancreatitis (14.3% and 4.8%, respectively). This result is in agreement with data reported from a Japanese study in which 13% of patients suffered cholangitis during biliary stenting[23]. Comparing this with long-term biliary stenting, Ang et al[24] reported up to 22% mortality among patients treated by long-term biliary stenting for an average of 12 mo (range: 1-54 mo), which accounted for 3.5% of biliary-related mortality. However, there was no mortality in the present study. Therefore, in the majority of patients, sequential biliary stenting was a safer and more effective procedure for treating difficult CBD stones than long-term biliary stenting. However, there were five cases (11.9%) where sequential biliary stenting failed in this study. The factors associated with the failure to achieve complete CBD stone clearance were unchanged CBD stone size at an average of 10 wk after the first biliary stenting attempt and a greater number of sessions performed (particularly for > 4 sessions). In cases presenting these particular factors, the therapeutic strategy should be changed from sequential biliary stenting to other alternative treatments such as intraductal lithotripsy (EHL or laser) or surgery. However, the current study did have some limitations similar to those in the other studies that included a retrospective case series of a limited number of patients. A multicenter study for a larger population should be conducted in the future.

In conclusion, sequential biliary stenting was an effective management strategy for large CBD stones that failed initial complete CBD clearance. The factors associated with failure were unchanged CBD stone size after the first biliary stenting procedure and a greater number of ERCP sessions performed.

We are grateful to Dr. Somchai Leelakusolvong, Dr. Nonthalee Pausawasdi, Dr. Thawatchai Akaraviputh, and Dr. Asada Methasate for allowing their clinical experiences (i.e., cases) to be included.

Common bile duct (CBD) stones and related complications are one of the most common pancreatobiliary diseases in daily practice. The treatment of choice for CBD stone removal is endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) with an 85%-90% success rate of complete stone removal. Complete removal is therefore not achieved for 10%-15% of CBD stones-particularly large stones-by the standard technique, and these may be managed conservatively by biliary stenting. The factors associated with the failure of this strategy are not well established.

Sequential biliary stenting has been used as an option for common bile duct stones that were not completely successfully removed following the first ERCP. The stent-stone friction force could lead to size-reduction or fragmentation of the stone.

The goal of this study was to determine the factors that are associated with the failure of ERCP. These factors will potentially aid endoscopists in making decisions of referring the patient for other treatment options such as laser choledochoscopy, electrohydraulic lithotripsy or even surgery.

This study suggested that the treatment strategies should be changed if the size of the CBD stone was not changed at 10 wk after the first procedure or failure of complete stone removal at the second attempt.

Sequential biliary stenting was the strategy of insertion the plastic stent over the CBD stone for two major reasons. First to maintain the drainage and second to aid in stone fragmentation after the stent was placed for more than 4-6 wk. The common interval for each procedure was 6-12 wk.

The present study demonstrated the parameters associated with the failure of sequential biliary stenting following unsuccessful stone removal from the large common bile duct. The authors found that sequential biliary stenting is an effective management strategy for treating failed initial large CBD stone removal.

P- Reviewer Rubio CA S- Editor Huang XZ L- Editor A E- Editor Zhang DN

| 1. | Attasaranya S, Fogel EL, Lehman GA. Choledocholithiasis, ascending cholangitis, and gallstone pancreatitis. Med Clin North Am. 2008;92:925-960, x. |

| 2. | Sherman S, Hawes RH, Lehman GA. Management of bile duct stones. Semin Liver Dis. 1990;10:205-221. |

| 3. | Lambert ME, Betts CD, Hill J, Faragher EB, Martin DF, Tweedle DE. Endoscopic sphincterotomy: the whole truth. Br J Surg. 1991;78:473-476. |

| 4. | Hwang JC, Kim JH, Lim SG, Kim SS, Shin SJ, Lee KM, Yoo BM. Endoscopic large-balloon dilation alone versus endoscopic sphincterotomy plus large-balloon dilation for the treatment of large bile duct stones. BMC Gastroenterol. 2013;13:15. |

| 5. | Cheng CL, Tsou YK, Lin CH, Tang JH, Hung CF, Sung KF, Lee CS, Liu NJ. Poorly expandable common bile duct with stones on endoscopic retrograde cholangiography. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:2396-2401. |

| 6. | Youn YH, Lim HC, Jahng JH, Jang SI, You JH, Park JS, Lee SJ, Lee DK. The increase in balloon size to over 15 mm does not affect the development of pancreatitis after endoscopic papillary large balloon dilatation for bile duct stone removal. Dig Dis Sci. 2011;56:1572-1577. |

| 7. | Yang J, Peng JY, Chen W. Endoscopic biliary stenting for irretrievable common bile duct stones: Indications, advantages, disadvantages, and follow-up results. Surgeon. 2012;10:211-217. |

| 8. | Tandan M, Reddy DN, Santosh D, Reddy V, Koppuju V, Lakhtakia S, Gupta R, Ramchandani M, Rao GV. Extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy of large difficult common bile duct stones: efficacy and analysis of factors that favor stone fragmentation. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;24:1370-1374. |

| 9. | Han J, Moon JH, Koo HC, Kang JH, Choi JH, Jeong S, Lee DH, Lee MS, Kim HG. Effect of biliary stenting combined with ursodeoxycholic acid and terpene treatment on retained common bile duct stones in elderly patients: a multicenter study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:2418-2421. |

| 10. | Katsinelos P, Fasoulas K, Paroutoglou G, Chatzimavroudis G, Beltsis A, Terzoudis S, Katsinelos T, Dimou E, Zavos C, Kaltsa A. Combination of diclofenac plus somatostatin in the prevention of post-ERCP pancreatitis: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Endoscopy. 2012;44:53-59. |

| 11. | Karaliotas C, Sgourakis G, Goumas C, Papaioannou N, Lilis C, Leandros E. Laparoscopic common bile duct exploration after failed endoscopic stone extraction. Surg Endosc. 2008;22:1826-1831. |

| 12. | Hochberger J, Tex S, Maiss J, Hahn EG. Management of difficult common bile duct stones. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2003;13:623-634. |

| 13. | Tanaka M. Bile duct clearance, endoscopic or laparoscopic? J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2002;9:729-732. |

| 14. | Williams EJ, Ogollah R, Thomas P, Logan RF, Martin D, Wilkinson ML, Lombard M. What predicts failed cannulation and therapy at ERCP? Results of a large-scale multicenter analysis. Endoscopy. 2012;44:674-683. |

| 15. | Lee TH, Han JH, Kim HJ, Park SM, Park SH, Kim SJ. Is the addition of choleretic agents in multiple double-pigtail biliary stents effective for difficult common bile duct stones in elderly patients? A prospective, multicenter study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;74:96-102. |

| 16. | McHenry L, Lehman G. Difficult bile duct stones. Curr Treat Options Gastroenterol. 2006;9:123-132. |

| 17. | Binmoeller KF, Schafer TW. Endoscopic management of bile duct stones. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2001;32:106-118. |

| 18. | Katsinelos P, Galanis I, Pilpilidis I, Paroutoglou G, Tsolkas P, Papaziogas B, Dimiropoulos S, Kamperis E, Katsiba D, Kalomenopoulou M. The effect of indwelling endoprosthesis on stone size or fragmentation after long-term treatment with biliary stenting for large stones. Surg Endosc. 2003;17:1552-1555. |

| 19. | Horiuchi A, Nakayama Y, Kajiyama M, Kato N, Kamijima T, Graham DY, Tanaka N. Biliary stenting in the management of large or multiple common bile duct stones. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;71:1200-1203.e2. |

| 20. | Chan AC, Ng EK, Chung SC, Lai CW, Lau JY, Sung JJ, Leung JW, Li AK. Common bile duct stones become smaller after endoscopic biliary stenting. Endoscopy. 1998;30:356-359. |

| 21. | Maxton DG, Tweedle DE, Martin DF. Retained common bile duct stones after endoscopic sphincterotomy: temporary and longterm treatment with biliary stenting. Gut. 1995;36:446-449. |

| 22. | Jain SK, Stein R, Bhuva M, Goldberg MJ. Pigtail stents: an alternative in the treatment of difficult bile duct stones. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;52:490-493. |

| 23. | Arya N, Nelles SE, Haber GB, Kim YI, Kortan PK. Electrohydraulic lithotripsy in 111 patients: a safe and effective therapy for difficult bile duct stones. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:2330-2334. |

| 24. | Ang TL, Fock KM, Teo EK, Chua TS, Tan J. An audit of the outcome of long-term biliary stenting in the treatment of common bile duct stones in a general hospital. J Gastroenterol. 2006;41:765-771. |