Published online May 16, 2013. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v5.i5.255

Revised: December 11, 2012

Accepted: January 5, 2013

Published online: May 16, 2013

Processing time: 242 Days and 23.8 Hours

Pancreatic pseudocysts (PP) arise from trauma and pancreatitis; endoscopic gastro-cyst drainage (EGCD) under endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) in symptomatic PP is the treatment of choice. Miniprobe EUS (MEUS) allows EGCD in children. We report our experience on MEUS-EGCD in PP, reviewing 13 patients (12 children; male:female = 9:3; mean age: 10 years, 4 mo; one 27 years, malnourished male Belardinelli-syndrome; PP: 10 post-pancreatitis, 3 post-traumatic). All patients underwent ultrasonography, computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging. Conservative treatment was the first option. MEUS EGCD was indicated for retrogastric cysts larger than 5 cm, diameter increase, symptoms or infection. EGCD (stent and/or nasogastrocystic tube) was performed after MEUS (20-MHz-miniprobe) identification of place for diathermy puncture and wire insertion. In 8 cases (61.5%), there was PP disappearance; one, surgical duodenotomy and marsupialization of retro-duodenal PP. In 4 cases (31%), there was successful MEUS-EGCD; stent removal after 3 mo. No complications and no PP relapse in 4 years of mean follow-up. MEUS EGCD represents an option for PP, allowing a safe and effective procedure.

- Citation: De Angelis P, Romeo E, Rea F, Torroni F, Caldaro T, Federici di Abriola G, Foschia F, Caloisi C, Lucidi V, Dall'Oglio L. Miniprobe EUS in management of pancreatic pseudocyst. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2013; 5(5): 255-260

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v5/i5/255.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v5.i5.255

Pancreatic pseudocysts (PP) in children arise from pancreatic trauma and acute pancreatitis with a blunt duct caused by several pancreatic diseases (i.e., Crohn’s disease, cystic fibrosis, pancreas divisum, etc.).

Diagnosis is performed by complete radiological evaluation that includes ultrasonography (US), computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI); serum amylase and imaging such as US are considered useful in monitoring the evolution, the occurrence of spontaneous resolution or the need for surgical intervention[1]. Herman et al[2] in a pediatric study in 2011 confirmed that maximal amylase (> 1100 U/L) is highly predictive of the risk of developing a pseudocyst.

Differential diagnosis is mandatory with neoplastic diseases like mucinous cystic neoplasia and acinar cell cyst adenoma, and also of other malformations such as gastric duplication[3-5].

Generally, conservative treatment is resolutive in most cases. According to D’Edigio et al[6], in 30%-50% of cases after a period of 6 wk, PP can resolve spontaneously.

Several operative therapies are described for PP: open surgery was the traditional treatment for symptomatic pseudo cysts and abscess, but morbidity and mortality were too high; laparoscopic cyst gastrostomy has also been described in children as a safe and effective technique which gives good results and a good rate of resolution[7].

Endoscopic transmural drainage, first introduced in the mid 1980s, has already been considered a minimally invasive, effective and safe approach in a series of adults affected by PP and abscesses, with success rates exceeding 90% among adults[8,9] and also among children, despite complications such as bleeding and technical difficulties[10-12].

During the last decade, in symptomatic long standing PP with a great increase in volume, endoscopic gastro-cyst drainage (EGCD) under endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) has become the chosen treatment; the endoscopic approach consists of the placement of a drainage catheter into the cysts under direct EUS guidance in order to identify the optimal site for puncture and stent placement, which guarantees greater safety and efficacy in both adults and children[12-14]. Barthet et al[15] proposed an algorithm for PP, including EUS-assisted drainage, transpapillary drainage and conventional endoscopic drainage, demonstrating that EUS is required for treatment in half of the cases. In children, few studies have been published on endoscopic marsupialization of PP with the addition of EUS; recent interesting data on ten children come from Jazrawi et al[9] with dedicated echo endoscopes[9].

The application of miniprobe endoscopic ultrasonography (MEUS) is not widespread. However, its use in pancreatobiliary disease allows the performance of complex procedures, especially in children and patients who have complications due to severe diseases[16]. The application of MEUS was never prescribed in the management of PP.

In this study, we report our experience of EGCD under MEUS guidance in PP. Between 2005-2010, 4 patients with PP were treated with EGCD under MEUS guidance; they were enrolled between 13 consecutive patients with PP followed in our unit. Conservative treatment was always the first option for all the patients.

MEUS EGCD was indicated in retro gastric cysts, with close contact between the cyst and the gastric wall, with cysts larger than 5 cm or that had increased in diameter, or in persistence of symptoms or infection.

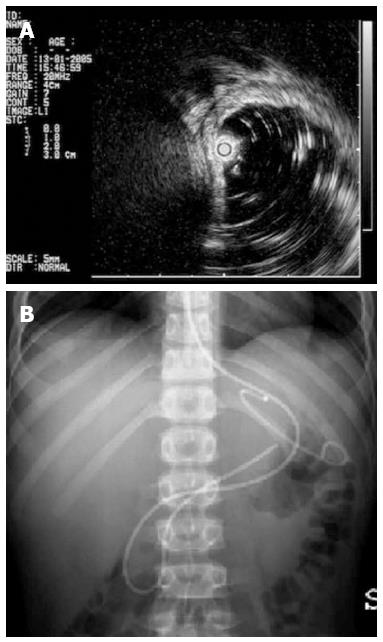

The steps of EUS guided drainage were the following: (1) endoscopy (GIF Q165-Q160 Olympus America Corp. Melville, NY) and EUS (20 MHz radial miniprobes Olympus UM-BS 20-26R, balloon sheath Olympus MAJ-643-R inserted through the 2.8 mm biopsy channel of an Olympus GIF Q165-Q160) confirmation of the best contact between the pseudocyst and the gastric wall and identification of the correct place for diathermy needle puncture; (2) according to the patient’s age and weight, exchange of the endoscope with a side view duodenoscope was opted for (Olympus TJF 160 VR), diathermy needle puncture (Cook Zimmon needle knife papillotome PTW-1 Wilson Cook Medical Ireland 5 Fr) of the gastric wall in the previously identified correct place, up to entering the cyst; (3) guide wire (0.035 IN) placement under X-ray control; (4) extraction of the needle with the guide in place and opacification of the cystic cavity; (5) hydrostatic balloon dilation of the cystic opening, if necessary; (6) washing of the cyst and the removal of necrotic tissue; and (7) insertion of a biliary drainage pigtail stent (Boston Scientific S.A. France) 7 or a 10 Fr stent gastro-cystic and/or nasal-gastro-cystic 7 Fr drainage. Nasal-gastro-cystic drainage was in place for one week; the stent was planned for three months.

ERCP (TJF 160 VR; Olympus America Corp. Melville, NY) and double sphincterotomy with stent placement and nasopancreatic tube were performed in communicating PP with the main pancreatic duct.

These procedures were always performed under general anesthesia with orotracheal intubation and in the supine position. During all the procedures X-ray was used. Antibiotic prophylaxis with cefazolin administered intravenously was given to all patients prior to endoscopy.

Surgery was preferred when the endoscopic approach was not suitable because there was no evidence of safe contact between the gastric or duodenal posterior wall and the PP, after evaluation by either endoscopy or MEUS.

Informed consent from patients and parents was asked for to enable us to collect and analyze data retrospectively in a confidential manner.

The ethics board of Bambino Gesù Children’s Hospital approved our study. Our series consisted of 12 children (male:female = 9:3) with a mean age of 124 mo (range 30 mo-16 years) and one adult (27 years old, male, Belardinelli syndrome, severe esophageal stricture and malnutrition, body mass index: 14 kg/m2) with PP (all chronic abdominal pain, 5 also had fever, one had enzyme elevation) due to pancreatitis (n = 10: biliary pancreatitis 1, idiopathic pancreatitis 6, mild cystic fibrosis 2, pancreas divisum 1) and trauma (n = 3).

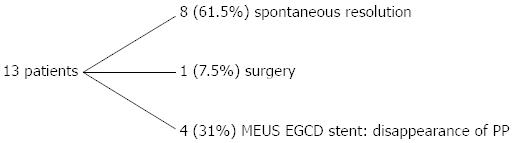

All patients underwent pancreatobiliary examinations, ultrasound, CT and cholangio-pancreatic MRI. The outcome of patients is reported in Figure 1.

In 8 cases (61.5%), we observed a progressive PP disappearance; one patient (7.5%) with pancreas divisum and relapsed acute pancreatitis required surgical duodenotomy and marsupialization of retro-duodenal PP due to incomplete MEUS contact between the PP and the duodenal wall.

In Table 1, results of MEUS EGCD were resumed; in 4 patients, 31% (males, 7, 10, 11 and 27 years; one trauma, 3 pancreatitis), successful MEUS EGCD (Figure 2) was performed with stent placement (in all the patients, one 7 Fr stent, in one patient also a 10 Fr stent). In all these patients, we observed a bulge of the gastric wall corresponding to the pseudocyst below.

| Sex | AgeBody weight | Associated disease | Etiology | PP size (cm) | PP site | EUS common wall thickness (mm) | Endoscopic treatment | FU yr |

| M | 7 yr | Filippi’s syndrome | Pancreatitis | 8 × 7 | Retrogastric | 4.5 | GIF Q165 pre-cut needle | 0.5 |

| 7 m | ||||||||

| 20 kg | 7Fr stent | |||||||

| M | 27 yr | Belardinelli’s syndrome-SEIP | Iatrogenic Biliary pancreatitis | 8 × 6 × 5 | Retrogastric | 3.5 | GIFQ165 pre-cut needle, hydrostatic dilation 7 and 10 Fr stent | 3 |

| 43 kg | ||||||||

| M | 11 yr | No | Trauma | 7 × 5 × 9 | Retrogastric and retroduodenal | 3.5 | Transduodenal drainage (TJF) GIFQ165, precut needle 7Fr and nasopancreatic tube | 6 |

| 31 kg | 10 × 5 × 11 | Pancreatic body and tail | ||||||

| M | 10 yr | Cystic fibrosis | Pancreatitis | 8 × 5 × 9 | Retrogastric | 3.8 | TJF double sphincterotomy GIFQ165 precut needle 7Fr stent and naso-pancreatic tube | 6 |

| 5 m | 9 × 6 × 10 | Pancreatic body and tail | ||||||

| 25 kg |

The patient with post traumatic PP was treated with naso-Wirsung drainage and a gastro-cystic pig tail stent (Figure 3), while those patients affected by cystic fibrosis and chronic pancreatitis even underwent sphincterotomy. Stent removal was performed after 3 mo in all patients. No immediate or late complications occurred and no relapse of PP in 4 years of mean follow up (range: 6 mo-6 years).

PP could be suspected in abdominal epigastric pain with an increase in pancreatic enzymes or biliary tree compression, after an acute pancreatitis or trauma (3-4 wk later). Non invasive radiological methods such as CT and MRI help to classify pancreatic trauma, contributing to planning the best and most adequate treatment. It is important to make a correct differential diagnosis for PP, even in pediatric cases.

Transient or persistent pancreatic duct disruption is the most common cause, but pancreatitis represents a spread factor on the basis of PP.

Pseudocysts frequently resolve spontaneously and so conservative treatment is the best option in children with PP. If the cyst is large with a persistency that goes beyond 6 wk, symptomatic and complicated by infection, it is correct to indicate the most appropriate treatment. Delgado Alvira et al[17], an interesting study on the best management strategies in PP, reported two children with post-traumatic PP and a large series reviewed by literature between 1990 and 2007. They underlined that asymptomatic PP in children does not require any specific intervention other than expectant management, while children with persistent clinical symptoms or those who develop complications may need further interventions such as external percutaneous drainage, cystogastrostomy, cystojejunostomy or pancreaticojejunostomy, endoscopic drainage or distal pancreatectomy[17].

Surgical treatment has been proposed by several authors: Briem-Richter et al[18] reported a rare case of pediatric Crohn’s disease with the development of huge pseudo cysts that required surgery; Yoder et al[7] described laparoscopic treatment that realized cystogastrostomy in 13 children, with a high rate of complete resolution with minimal morbidity and rapid recovery.

During the last decade, it was gradually recognized that endoscopic treatment could be the preferred approach to manage PP[15]. In 2004, Al-Shanafey et al[19] had successfully treated two children with transpapillary drainage and one child with an endoscopic cystoduodenostomy.

The endoscopic therapeutic approach consists of transduct (transpapillar in recent Wirsung disruption) or transmural passage of a guide wire with stent placement to the drainage of the pseudo cyst content[20], under EUS evaluation or through linear echo-endoscope (duodenal-cyst drainage or gastro-cyst drainage), almost 6 wk from evidence of a pseudo cyst[21]. A 15% recurrence rate has been reported. If pseudo cysts persist lifelong, surgery is recommended.

Major ductal injuries caused by blunt abdominal trauma are rare and treated by surgery. ERCP with stent placement is useful to manage post-traumatic pseudo cysts, with rapid clinical improvement and complete resolution of clinical and biochemical pancreatitis.

Barthert et al[15] in 2008 in a prospective study based on a systematic treatment algorithm concluded that endoscopic drainage is the first-line method of managing PP and EUS is required in half of the cases to obtain a definitive therapy.

EUS is already widespread in pediatric cases, but experience in pancreatobiliary disease is poor[11]; pediatric experiences of EUS guided endoscopic treatment are very much limited due to several technical difficulties, few experienced centers and few case studies.

According to a study by Varadarajulu et al[13] in 2005, EUS could give a diagnostic contribution to chronic pancreatitis, in pancreatic pseudo-cysts, in coledocho-litiasis, in pancreas divisum and in duodenal duplications, because EUS can also be successfully performed in children aged 5 years and over using an adult echo endoscope. Cohen et al[22] in 2008 verified the diagnostic impact of EUS, with a demonstration of a radical change of diagnostic and therapeutic strategies when this procedure was used.

In pediatric cases, EUS improved diagnostic and the therapeutic possibility of ERCP in chronic and recurrent pancreatitis, in treatment of pancreatic pseudocysts (gastrocystostomy EUS guided) and duodenal duplication (endoscopic therapy).

Even if endoscopic drainage of PP is successfully reported in children, EUS could add safety to the procedure. In 2010, Theodoros et al[23] published the case of a child with post-traumatic PP who was successfully treated with a guided EUS transgastric approach. Jazrawi et al[9] reported the largest series of pediatric patients with symptomatic PP due to pancreatitis and trauma; in all ten cases, successful EUS guided transgastric endoscopic drainage was achieved, with placement of double pig tail stents in eight patients and complete cyst aspiration and collapse by EUS fine-needle aspiration in two cases.

Miniprobe was never described in PP management; this technique is useful in small children and in particular situations such as esophageal stricture that does not allow a dedicated echo endoscope passage. This technique is safe and simple, even with a common endoscope.

The advantages of miniprobe EUS are numerous. We have the possibility of performing therapeutic procedures even when dedicated radial and linear echo endoscopes are not available; the MEUS equipment is less expensive than instruments and the ultrasound generator for linear EUS. MEUS also represents a useful instrument in pediatric surgery and pediatric endoscopy for many other different clinical situations, such as duodenal duplications[16], esophageal congenital strictures[24] and duodenal diaphragms[25]. Generally, we perform EUS with standard front view endoscope to avoid miniprobe damage by the cannula elevator of side view duodenoscope; besides, we can use a small caliber endoscope (operative channel of 2.2 to allow miniprobe passage) with a “frontal vision” commonly used in the clinical practice, to complete the endoscopic therapy.

Miniprobe EUS has an indication in malnourished, small weight patients, syndromic or sick patients in a general bad condition (i.e., cystic fibrosis) and in esophageal stenosis with consequent difficulty of the passage of the echo endoscope. The limitations of this procedure are the lack of a Doppler and difficulty to rule out with certainty the presence of vessels in the common wall with confirmation of blood flow; daily experience allows ascertaining suspected vascular structures inside the wall.

In our small series of four patients, we have applied this innovative technique in special patients, two syndromic cases (one with neurological retardation, Filippi’s syndrome and the other with an esophageal stricture and Belardinelli’s syndrome), one cystic fibrosis child and a complex post-traumatic patient. Their clinical conditions and associated diseases contributed to determine a complex approach. Our experience with EUS miniprobe commonly used in our tertiary center for other diseases (i.e., congenital esophageal stenosis, duodenal duplications, duodenal diaphragms, etc.) and with pediatric operative endoscopy allowed us to choose this original procedure in our cases and in one case in particular. The daily availability of digestive surgery gives us the possibility to choose the best treatment depending on specific situations, achieving an outcome for patients similar to the literature. While the unavailability of echo endoscope limits our decision making, on the other hand, we need a simple, rapid, safe technique, easy to reproduce, that could be taught during training.

Small series size does not allow a deep analysis that larger cases need to be able to confirm our preliminary data. The choice of the typology of endoscope to perform the puncture of the cyst depends on the availability of a side view adult duodenoscope, the age and weight of the patient, and the possible presence of esophageal stricture. We prefer to use the duodenoscope because it provides the best position in front of the gastric wall and the opportunity to insert large diameter stents.

The choice of the best treatment for PP depends on the medical-surgical team’s experience and the management of the endoscopic technique, as well as the availability of interventionist radiology and dedicated pediatric accessories[17]. Despite several techniques, PP therapy remains a challenge for both pediatric surgeons and pediatric endoscopists[23]. A novel hybrid natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery has already been reported by Rossini et al[26]; probably, in the future, the model of a transgastric approach used to treat PP could be applied in several diseases, even in pediatric cases.

We can conclude that when conservative therapy is ineffective, EGCD represents a viable option to resolve PP permanently. MEUS provides a valuable contribution to help endoscopic cystogastrostomy in children and also in difficult situations, allowing a safe and effective endoscopic procedure.

We thank Vises Onlus and Generazione Sviluppo Onlus for their financial support.

P- Reviewers Fusaroli P, Cheon YK, Cohen S, Katanuma A S- Editor Song XX L- Editor Roemmele A E- Editor Zhang DN

| 1. | Chen KH, Hsu HM, Hsu GC, Chen TW, Hsieh CB, Liu YC, Chan DC, Yu JC. Therapeutic strategies for pancreatic pseudocysts: experience in Taiwan. Hepatogastroenterology. 2008;55:1470-1474. |

| 2. | Herman R, Guire KE, Burd RS, Mooney DP, Ehlrich PF. Utility of amylase and lipase as predictors of grade of injury or outcomes in pediatric patients with pancreatic trauma. J Pediatr Surg. 2011;46:923-926. |

| 3. | Volkan Adsay N. Cystic lesions of the pancreas. Mod Pathol. 2007;20 Suppl 1:S71-S93. |

| 4. | McEvoy MP, Rich B, Klimstra D, Vakiani E, La Quaglia MP. Acinar cell cystadenoma of the pancreas in a 9-year-old boy. J Pediatr Surg. 2010;45:e7-e9. |

| 5. | Ratan SK, Ratan KN, Bishnoi K, Jhanwar A, Kaushik V, Makkar A. Gastric duplication cysts: diagnostic dilemma with pancreatic pseudocysts. Trop Gastroenterol. 2010;31:129-130. |

| 6. | D’Egidio A, Schein M. Pancreatic pseudocysts: a proposed classification and its management implications. Br J Surg. 1991;78:981-984. |

| 7. | Yoder SM, Rothenberg S, Tsao K, Wulkan ML, Ponsky TA, St Peter SD, Ostlie DJ, Kane TD. Laparoscopic treatment of pancreatic pseudocysts in children. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2009;19 Suppl 1:S37-S40. |

| 8. | Lopes CV, Pesenti C, Bories E, Caillol F, Giovannini M. Endoscopic-ultrasound-guided endoscopic transmural drainage of pancreatic pseudocysts and abscesses. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2007;42:524-529. |

| 9. | Jazrawi SF, Barth BA, Sreenarasimhaiah J. Efficacy of endoscopic ultrasound-guided drainage of pancreatic pseudocysts in a pediatric population. Dig Dis Sci. 2011;56:902-908. |

| 10. | Breckon V, Thomson SR, Hadley GP. Internal drainage of pancreatic pseudocysts in children using an endoscopically-placed stent. Pediatr Surg Int. 2001;17:621-623. |

| 11. | Varadarajulu S, Wilcox CM, Hawes RH, Cotton PB. Technical outcomes and complications of ERCP in children. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;60:367-371. |

| 12. | Antillon MR, Shah RJ, Stiegmann G, Chen YK. Single-step EUS-guided transmural drainage of simple and complicated pancreatic pseudocysts. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;63:797-803. |

| 13. | Varadarajulu S, Wilcox CM, Eloubeidi MA. Impact of EUS in the evaluation of pancreaticobiliary disorders in children. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;62:239-244. |

| 14. | Mas E, Barange K, Breton A, de Maupéou F, Juricic M, Broué P, Olives JP. Endoscopic cystostomy for posttraumatic pseudocyst in children. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2007;45:121-124. |

| 15. | Barthet M, Lamblin G, Gasmi M, Vitton V, Desjeux A, Grimaud JC. Clinical usefulness of a treatment algorithm for pancreatic pseudocysts. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;67:245-252. |

| 16. | Romeo E, Torroni F, Foschia F, De Angelis P, Caldaro T, Santi MR, di Abriola GF, Caccamo R, Monti L, Dall’Oglio L. Surgery or endoscopy to treat duodenal duplications in children. J Pediatr Surg. 2011;46:874-878. |

| 17. | Delgado Alvira R, Elías Pollina J, Calleja Aguayo E, Martínez-Pardo NG, Esteban Ibarz JA. [Pancreatic pseudocyst: less is more]. Cir Pediatr. 2009;22:55-60. |

| 18. | Briem-Richter A, Grabhorn E, Wenke K, Ganschow R. Hemorrhagic necrotizing pancreatitis with a huge pseudocyst in a child with Crohn’s disease. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;22:234-236. |

| 19. | Al-Shanafey S, Shun A, Williams S. Endoscopic drainage of pancreatic pseudocysts in children. J Pediatr Surg. 2004;39:1062-1065. |

| 20. | Canty TG, Weinman D. Treatment of pancreatic duct disruption in children by an endoscopically placed stent. J Pediatr Surg. 2001;36:345-348. |

| 21. | Sharma SS, Maharshi S. Endoscopic management of pancreatic pseudocyst in children-a long-term follow-up. J Pediatr Surg. 2008;43:1636-1639. |

| 22. | Cohen S, Kalinin M, Yaron A, Givony S, Reif S, Santo E. Endoscopic ultrasonography in pediatric patients with gastrointestinal disorders. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2008;46:551-554. |

| 23. | Theodoros D, Nikolaides P, Petousis G. Ultrasound-guided endoscopic transgastric drainage of a post-traumatic pancreatic pseudocyst in a child. Afr J Paediatr Surg. 2010;7:194-196. |

| 24. | Romeo E, Foschia F, de Angelis P, Caldaro T, Federici di Abriola G, Gambitta R, Buoni S, Torroni F, Pardi V, Dall’oglio L. Endoscopic management of congenital esophageal stenosis. J Pediatr Surg. 2011;46:838-841. |

| 25. | Torroni F, De Angelis P, Caldaro T, di Abriola GF, Ponticelli A, Bergami G, Dall’Oglio L. Endoscopic membranectomy of duodenal diaphragm: pediatric experience. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;63:530-531. |

| 26. | Rossini CJ, Moriarty KP, Angelides AG. Hybrid notes: incisionless intragastric stapled cystgastrostomy of a pancreatic pseudocyst. J Pediatr Surg. 2010;45:80-83. |