Published online May 16, 2013. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v5.i5.246

Revised: February 12, 2013

Accepted: February 28, 2013

Published online: May 16, 2013

AIM: To further reduce the risk of bleeding or bile leakage.

METHODS: We performed endoscopic ultrasound guided biliary drainage in 6 patients in whom endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) had failed. Biliary access of a dilated segment 2 or 3 duct was achieved from the stomach using a 19G needle. After radiologically confirming access a guide wire was placed, a transhepatic tract created using a 6 Fr cystotome followed by balloon dilation of the stricture and antegrade metallic stent placement across the malignant obstruction. This was followed by placement of an endocoil in the transhepatic tract.

RESULTS: Dilated segmental ducts were observed in all patients with the linear endoscopic ultrasound scope from the proximal stomach. Transgastric biliary access was obtained using a 19G needle in all patients. Biliary drainage was achieved in all patients. Placement of an endocoil was possible in 5/6 patients. All patients responded to biliary drainage and no complications occurred.

CONCLUSION: We show that placing endocoils at the time of endoscopic ultrasound guided biliary stenting is feasible and may reduce the risk of bleeding or bile leakage.

- Citation: van der Merwe SW, Omoshoro-Jones J, Sanyika C. Endocoil placement after endoscopic ultrasound-guided biliary drainage may prevent a bile leak. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2013; 5(5): 246-250

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v5/i5/246.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v5.i5.246

Advanced biliary tract malignancy complicated by obstructive jaundice has traditionally been managed by palliative stent placement during endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP). In 3%-12% of patients with advanced disease tumour involvement of the small bowel or peri-ampullary region may preclude the use of ERCP, necessitating percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage (PTBD) or surgery[1]. However, surgery has been associated with high complication rates and morbidity[2,3]. In recent years various groups have described endoscopic ultrasound guided access of the left system, allowing placement of metal or plastic stents either across the distal stricture or in the stomach (hepatico-gastrostomy), with high technical success[4,5]. Since the initial case series which described the feasibility of endoscopic ultrasound guided biliary drainage, various groups mainly from tertiary care academic expert centres have reported similar success rates in small case series[6-8]. However, various obstacles still exist to extending the general applicability of this technique outside expert centres. Firstly, no randomized control trials exist comparing the safety and efficacy of endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) biliary access to percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography (PTC). Secondly, current endoscopic techniques utilize standard endoscopic accessories not specifically developed for use within the biliary system when advanced through the gastric wall. Thirdly, specific EUS strategies are needed to prevent or reduce complications associated with percutaneous approaches. We used an endocoil in the transhepatic tract following biliary access and stent placement to further reduce the risk of bleeding or bile leakage.

All procedures were performed in an expert referral centre for biliary interventional endoscopy where patients undergoing ERCP for drainage of malignant biliary tract disease are routinely asked to consent to possible EUS-guided biliary drainage in the event of ERCP failure to obtain access. Consensus was always reached between the hepatobiliary surgeon (JO), the interventional radiologist (CS) and the hepatobiliary endoscopist (SvdM) regarding the optimal management of the patient. All EUS-guided biliary access procedures were prospectively entered into a database. All except one patient received general anaesthesia, and were intubated and mechanically ventilated in the supine position for the duration of the procedures (Table 1).

| Age (yr) | Cancer diagnosis | Procedures performed | SEMS (cm × cm) | Technical success | Clinical success | Complications |

| 67 | Locally advanced | ERCP | 8 × 10 | Yes | Yes | None |

| Pancreatic | EUS-BD + coil | uncovered | ||||

| 50 | Metastatic | ERCP | 8 × 10 | Yes | Yes | None |

| pancreatic | EUS-BD + coil | uncovered | ||||

| Duodenal wall stent | ||||||

| 46 | Infiltrating | ERCP | 8 × 10 | Yes | Yes | None |

| gallbladder | EUS-BD + coil | uncovered | ||||

| 80 | Ampullary | ERCP | 8 × 10 | Yes | Yes | None |

| EUS-BD + coil | uncovered | |||||

| Duodenal wall stent | ||||||

| 44 | Metastatic | ERCP | 8 × 10 | Yes | Yes | None |

| Ovarian | EUS-BD + coil | uncovered | ||||

| 77 | Pancreatic | ERCP | 6 × 10 | Failed EUS-BD, | Yes | None |

| EUS-BD | covered | Successful | ||||

| EUS-choledochoenterostomy | EUS-choledochoenterostomy |

A 67-year-old female presented with obstructive jaundice. Spiral computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen showed unresectable locally-advanced pancreatic carcinoma. At ERCP the ampulla could not be identified due to extensive tumour infiltration of the duodenal wall.

A 50-year-old female patient was referred with metastatic pancreatic carcinoma with duodenal infiltration and liver metastasis. She also suffered from type II diabetes and systolic arterial hypertension. At ERCP the ampulla could not be identified in the tumour mass.

A 46-year-old-female patient was diagnosed with unresectable locally advanced gallbladder carcinoma invading the common bile duct. The patient was managed by percutaneous drainage of both the left and right systems after ERCP failed. However, the stricture could not be transversed and external drainage catheters were placed during interventional radiology. The patient developed cholangitis. EUS-guided biliary access was requested to internalize biliary drainage. After EUS biliary access was achieved, a guidewire could be placed across a long stricture into the duodenum.

An 80-year-old male presented with obstructive jaundice. Spiral CT of the abdomen showed dilated intra- and extrahepatic bile ducts with the common bile duct (CBD) dilated up to the level of the ampulla where a mass lesion was seen. He was also known to have alcoholic liver disease. Spiral CT also showed evidence of liver cirrhosis and ascites in the upper abdomen. The patient had severe obstructive airway disease with type I respiratory failure and was oxygen dependent. A large peri-ampullary mass was confirmed by ERCP but the ampulla could not be identified. Due to the presence of ascites between the liver and the lateral abdominal wall, a PTC could not be considered. Endoscopic ultrasound showed no fluid between the stomach and the liver capsule and EUS guided biliary drainage was performed under light conscious sedation.

A 44-year-old female patient diagnosed with stage IV metastatic ovarian cancer with liver metastasis and lymph node masses in the porta hepatis, presented with obstructive jaundice and ascites. Because of her age, third line chemotherapy was considered, but toxicity concerns because of severe cholestasis necessitated biliary drainage before chemotherapy could commence. Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography showed a mid-CBD stricture, a common bile duct severely displaced by the tumour and dilated intrahepatic ducts. Biliary cannulation was achieved during ERCP but the guidewire could not be advanced past the stricture into the proximal biliary tract. Ascites precluded the use of PTC. After successful EUS access was achieved, a guidewire could be passed into the duodenum.

A 77-year-old female patient was diagnosed with locally advanced pancreatic carcinoma with duodenal infiltration and hypertensive cardiomyopathy. ERCP failed to identify the ampulla due to duodenal infiltration. She was not considered for surgery due to underlying co-morbidity and was referred for EUS-guided biliary drainage.

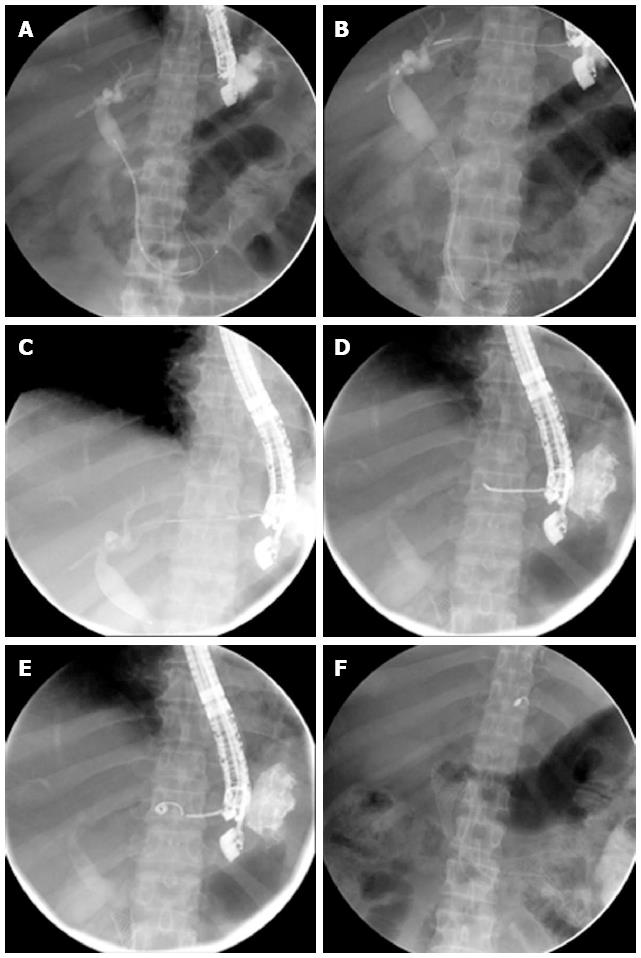

Linear array endoscopic ultrasound (Pentax Hitachi 7500; Pentax Hitachi, Montvale, NJ) was used to identify the dilated left system. The Doppler mode was used to differentiate intrahepatic bile ducts from portal and hepatic vein branches. A 19G needle (Cook Medical, Limerick, Ireland) was used to puncture a peripherally located dilated segment 2 or 3 duct under EUS guidance. Under fluoroscopic control a cholangiogram was obtained and a standard 0.035 guidewire was advanced into the biliary system. Next, a 6Fr cystotome (Endoflex, Voerde, Germany) was used to create a transgastric tract through the liver parenchyma into the biliary system. A 0.038 catheter was advanced over the wire into the biliary system and advanced to the bifurcation. The guidewire was then manipulated across the stricture and into the duodenal lumen (Figure 1). A Hurricane biliary dilation balloon 4 cm × 4 mm (Boston Scientific, Natick, MA Boston Scientific) was advanced through the tract and used to dilate the common bile duct stricture without balloon dilation at the level of the gastric wall liver interface. A 10 mm × 80 mm uncovered metal stent (Boston) was advanced and deployed under fluoroscopy across the papilla and past the duodenal obstruction, when present. To reduce the risk of a bile leak the catheter was withdrawn using contrast injection to verify anatomy, and carefully positioned in the track between the liver capsule and dilated system with the guidewire still in place in the biliary system. The guide wire was then removed and an endocoil (0.035” Fibered Platinum Coils, 6 mm, Boston Scientific, Natick, MA Boston Scientific) loaded into the lumen of a 0.038 prototype catheter before advancing it using a 0.035 guidewire (Boston Scientific, Natick, MA Boston Scientific) under EUS and fluoroscopy guidance (Figure 1).

Transgastric EUS-guided biliary access was successful in 5 of 6 patients. In one patient (patient 6) transgastric biliary access was initially possible and a cholangiogram obtained but guidewire cannulation could not be achieved. The patient was rescued by EUS-guided retrograde placement of a transduodenal covered stent (choledocho-enterostomy) above the malignant stricture. In all cases no immediate procedure-related complications were observed. Two cases necessitated further duodenal stent placement during the same session. The mean procedure time (including anaesthesia) was 91 min (49-133). Levofloxacine (500 mg) was administered at the time of the procedure and continued for 5 d. Mild abdominal pain, not accompanied by peritoneal guarding and responding to Tramadol was experienced by two patients and resolved within 4 h. At 30 d all patients had responded with normalization of cholestasis and no late complications, including infections, were observed.

In patients with advanced biliary tract malignancy extensive peri-ampullary and duodenal infiltration may occur that may prevent the use of ERCP for palliative stent placement. Under these circumstances percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage is often utilized. PTBD necessitates transversing of the parietal and visceral peritoneum, potentially causing bile leakage and bleeding into the peritoneal cavity. This procedure is also associated with significant pain, lengthy hospital stays and an overall reduction in quality of life[9]. Severe complications following PTBD including peritonitis, sepsis, bleeding requiring re-intervention, and even procedure-related mortality have been well described[9,10]. Indeed, The Society of Interventional Radiology (SIR) quality improvement guidelines established the procedural risk of severe major complications at 2.5%[11].

Embolization of biliary tracts using different materials including gel foam, fibrin glue, n-butyl cyanoacrylate and endocoils are routinely used in clinical practice at the time when biliary catheters are removed, in order to reduce the risk of bile leakage or bleeding. A recent randomized trial showed that transhepatic biliary tract embolization with n-butyl cyanoacrylate decreased both pain perception as assessed by a visual analog score and the need for analgesia, when compared to the non-embolization group[12]. Endocoil placement is a well-established intervention radiology technique where coils placed in blood vessels (endovascular coils) obliterate flow and induce coagulation, thrombosis and the formation of neo-intimal proliferation[13]. Coils have also been used outside the vascular setting, such as in coil embolization of needle tracks following PTC[14]. In theory, such coils will obstruct the flow of bile, prevent leaking and induce a local tissue response, in the same way gel foam.

Recent advances in endoscopic ultrasound have allowed access to a dilated biliary system through either retrograde or anterograde approaches. Retrograde cannulation, normally performed from the duodenal bulb, allows access to the biliary tract above a malignant stricture with the intent either to pass a guide wire through the papilla and then perform a rendezvous procedure, or to place a covered metal stent in the stomach[15]. Cannulation of a dilated segment 2 or 3 sectoral duct is also possible from the proximal stomach where the endoscopist performs all procedures in an antegrade fashion[8]. Currently these procedures are selectively performed in specialist centres by expert endoscopists. Overall, EUS biliary drainage is technically successful in 75%-92% of cases, although there have been reports of bile leakage and peritonitis[8]. Endoscopic ultrasound utilizes standard endoscopic accessories and there is a need to create a transhepatic tract, using a 6Fr cystotome, to allow passage of stents from the stomach across biliary strictures. These accessories were not developed for use in EUS settings and are more difficult to use when advanced through the gastric wall. Valid concerns therefore still exist regarding the overall risk of bile leaks, peritonitis, and safety in EUS-guided biliary drainage. Ways should be developed by which these procedures may be improved and the risk of complications decreased. EUS guided biliary drainage theoretically exposes a tract between the dilated left system and the peritoneum.

Here we report the placement of an endocoil through a 0.038 catheter after completion of EUS-guided transgastric stent placement. The catheter was slowly withdrawn and positioned between the dilated sectoral duct and the liver capsule and a standard 0.035 guidewire was used to advance the coil into the tract created by the 6Fr cystotome. We could demonstrate that the placement of an endocoil is safe in all patients and does not add to the overall complexity of the procedure. Endocoil placement is however not possible through a standard ERCP catheter with internal lumen diameters of 0.035, probably because of the angulation as it passes through the gastric wall and liver parenchyma. Catheters with larger internal lumen, at least 0.038 in diameter, are therefore needed. Currently such catheters do not exist, underscoring the need to develop catheters specific for EUS-guided biliary access. It remains to be seen whether coil placement will improve the overall safety of EUS transgastric procedures in the future. Randomized pilot studies will be needed to determine the usefulness this technique may offer over PTC in the prevention of bile leaks when accessing the biliary tract by EUS.

Advanced biliary tract malignancy, complicated by obstructive jaundice is managed by endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) and stent placement. In some patients ERCP is not possible due to duodenal or peri-ampullary infiltration, necessitating percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography.

In recent years developments in endoscopic ultrasound have made it possible to gain access to a dilated left biliary system from the stomach. However only case series from expert medical centres have been reported. It therefore remains important to develop safer endoscopic techniques that can be used more widely and to compare endoscopic ultrasound guided biliary drainage with percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage in randomized controlled trials.

Here the authors describe placement of an endocoil in the transhepatic tract following endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) guided biliary drainage. The authors propose that placement of an endocoil may prevent leakage of bile to the peritoneum and may thus improve the safety of EUS guided transgastric biliary drainage.

In remains imperative that further development in the field of interventional endoscopic ultrasound should be undertaken and that accessories specific for endoscopic ultrasound applications should be developed. This will improve efficacy and safety.

Endoscopic ultrasound guided biliary drainage refers to the use of EUS in visualizing a dilated left biliary system. This is followed by gaining access to a dilated sectoral duct segment 2, 3 using a 19G endoscopic ultrasound needle. When this is established a guide wire can be passed into the biliary system and advanced past a malignant stricture so that a stent can be placed. This technology has theoretical benefits over percutaneous biliary drainage.

Biliary leakage is very rare after balloon dilataion of biliary stenosis followed by self-expandable metallic stent. This manuscript could be accepted after revision.

P- Reviewer Chow WK S- Editor Song XX L- Editor Hughes D E- Editor Zhang DN

| 1. | Giovannini M, Pesenti Ch, Bories E, Caillol F. Interventional EUS: difficult pancreaticobiliary access. Endoscopy. 2006;38 Suppl 1:S93-S95. |

| 2. | Smith AC, Dowsett JF, Russell RC, Hatfield AR, Cotton PB. Randomised trial of endoscopic stenting versus surgical bypass in malignant low bileduct obstruction. Lancet. 1994;344:1655-1660. |

| 3. | Stoker J, Laméris JS. Complications of percutaneously inserted biliary Wallstents. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 1993;4:767-772. |

| 4. | Burmester E, Niehaus J, Leineweber T, Huetteroth T. EUS-cholangio-drainage of the bile duct: report of 4 cases. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;57:246-251. |

| 5. | Giovannini M, Dotti M, Bories E, Moutardier V, Pesenti C, Danisi C, Delpero JR. Hepaticogastrostomy by echo-endoscopy as a palliative treatment in a patient with metastatic biliary obstruction. Endoscopy. 2003;35:1076-1078. |

| 6. | Bories E, Pesenti C, Caillol F, Lopes C, Giovannini M. Transgastric endoscopic ultrasonography-guided biliary drainage: results of a pilot study. Endoscopy. 2007;39:287-291. |

| 7. | Park do H, Song TJ, Eum J, Moon SH, Lee SS, Seo DW, Lee SK, Kim MH. EUS-guided hepaticogastrostomy with a fully covered metal stent as the biliary diversion technique for an occluded biliary metal stent after a failed ERCP (with videos). Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;71:413-419. |

| 8. | Nguyen-Tang T, Binmoeller KF, Sanchez-Yague A, Shah JN. Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS)-guided transhepatic anterograde self-expandable metal stent (SEMS) placement across malignant biliary obstruction. Endoscopy. 2010;42:232-236. |

| 9. | Stoker J, Laméris JS, Jeekel J. Percutaneously placed Wallstent endoprosthesis in patients with malignant distal biliary obstruction. Br J Surg. 1993;80:1185-1187. |

| 10. | Sut M, Kennedy R, McNamee J, Collins A, Clements B. Long-term results of percutaneous transhepatic cholangiographic drainage for palliation of malignant biliary obstruction. J Palliat Med. 2010;13:1311-1313. |

| 11. | Saad WE, Wallace MJ, Wojak JC, Kundu S, Cardella JF. Quality improvement guidelines for percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography, biliary drainage, and percutaneous cholecystostomy. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2010;21:789-795. |

| 12. | Vu DN, Strub WM, Nguyen PM. Biliary duct ablation with N-butyl cyanoacrylate. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2006;17:63-69. |

| 13. | Lyon SM, Terhaar O, Given MF, O’Dwyer HM, McGrath FP, Lee MJ. Percutaneous embolization of transhepatic tracks for biliary intervention. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2006;29:1011-1014. |

| 14. | Raymond J, Darsaut T, Salazkin I, Gevry G, Bouzeghrane F. Mechanisms of occlusion and recanalization in canine carotid bifurcation aneurysms embolized with platinum coils: an alternative concept. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2008;29:745-752. |

| 15. | Hara K, Yamao K, Niwa Y, Sawaki A, Mizuno N, Hijioka S, Tajika M, Kawai H, Kondo S, Kobayashi Y. Prospective clinical study of EUS-guided choledochoduodenostomy for malignant lower biliary tract obstruction. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:1239-1245. |