Published online May 16, 2013. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v5.i5.219

Revised: July 13, 2012

Accepted: March 15, 2013

Published online: May 16, 2013

AIM: To investigate the feasibility of small bowel polypectomy using double balloon enteroscopy and to evaluate the correlation with capsule endoscopy (CE).

METHODS: This is a retrospective review of a single tertiary hospital. Twenty-five patients treated by enteroscopy for small bowel polyps diagnosed by CE or other imaging techniques were included. The correlation between CE and enteroscopy (correlation coefficient of Kendall for the number of polyps, intra-class coefficient for the size and coefficient of correlation kappa for the location) was evaluated.

RESULTS: There were 31 polypectomies and 12 endoscopic mucosal resections with limited morbidity and no mortality. Histological analysis revealed 27 hamartomas, 6 adenomas and 3 lipomas. Strong agreement between CE and optical enteroscopy was observed for both location (Kappa value: 0.90) and polyp size (Kappa value: 0.76), but only moderate agreement was found for the number of polyps (Kendall value: 0.47).

CONCLUSION: Double balloon enteroscopy is safe for performing polypectomy. Previous CE is useful in selecting the endoscopic approach and to predicting the difficulty of the procedure.

- Citation: Rahmi G, Samaha E, Lorenceau-Savale C, Landi B, Edery J, Manière T, Canard JM, Malamut G, Chatellier G, Cellier C. Small bowel polypectomy by double balloon enteroscopy: Correlation with prior capsule endoscopy. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2013; 5(5): 219-225

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v5/i5/219.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v5.i5.219

The main indication for double balloon enteroscopy (DBE) and capsule endoscopy (CE) is the endoscopic exploration of patients with obscure gastrointestinal bleeding[1-5]. Small bowel polyps and tumours are important causes of small bowel pathology, which occur most frequently in familial or non-familial polyposis syndromes[1,6-10]; the most frequent are familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) and Peutz-Jeghers syndrome (PJS)[11,12]. The advent of CE and DBE has improved our ability to perform deep exploration of the small bowel. DBE has the additional advantage of permitting the retrieval of tissue and removal of premalignant polyps. The primary aim of the present study was to assess the feasibility of polypectomy by DBE in patients with small bowel polyps diagnosed by CE or other imaging techniques including computer tomography (CT) scan and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). The secondary aim was to evaluate the correlation between CE and DBE in terms of determining the size, location and number of polyps.

This retrospective cohort study included patients treated by DBE for small bowel polyps diagnosed with CE (84%) or other imaging techniques (16% of cases) in our tertiary referral centre between January 2005 and January 2008. Patients were included or excluded based on the following keywords in the CE or radiology reports: (1) Inclusion criteria for CE were “pedunculated or sessile polyps” and for MRI or abdominal CT scan “lesions with polyp aspects”; (2) Exclusion criteria for CE were “the tumour or mass appears as a thickened fold with pathologically abnormal vessels, aspects of stenosis, aspects of diffuse infiltration of the small bowel wall and aspects of submucosal lesions with intact overlying mucosa”, and MRI or abdominal CT scan “the tumour or mass appears with tissue density picture and aspects of stenosis”.

All patients had previously undergone at least one upper gastrointestinal endoscopy and colonoscopy. The data were obtained from the patient medical records and were entered into a semi-standardised electronic database. If one DBE route did not yield a diagnosis, the opposite route was used for the second investigation. Complete DBE was confirmed by tattooing the small bowel.

The lesions diagnosed by the physician in charge of interpreting CE were classified according to their size, location and imputability according to Saurin et al[13], using the following criteria: P3 (presence of blood), P2 (high imputability), P1 (intermediate imputability) and P0 (low imputability). Capsule video endoscopy was performed with the PillCam™ SB (Given Imaging Ltd, Yoqneam, Israel). All patients were prepared with 2 L of polyethylenglycol (PEG) solution the night before examination. The capsule transmitted continuous video images at a rate of 2 frames per second for about 8 h during its passage through the gastrointestinal tract. The route of insertion of the DBE was found by calculating Gay’s index; the oral route was chosen if the time to lesion/time to cecum was less than 0.75[14]. The oral and anal routes were not taken during the same procedure because of the long procedure duration. In our series, no patients received total enteroscopy. For 6 patients, DBE from the anal route permitted the resection of polyps. For one patient, CE showed polyps in the jejunum and ileum, and DBE by the oral and anal routes was performed 48 h apart for the resection of these polyps. We failed to perform a complete enteroscopy. For the other 5 patients, CE showed polyps in the ileal position; in these cases, DBE by the anal route was the first choice and permitted the resection of polyps.

The following locations were examined: the proximal jejunum (the first quarter of the small intestine), distal jejunum (the second quarter of the small intestine), proximal ileum (the third quarter of the small intestine) and distal ileum (the fourth quarter of the small intestine). No a posteriori readings of CE or DBE were performed.

All of the DBE procedures were performed by an experienced endoscopists aided by an assistant holding the overtube. The DBEs (Fujinon Inc., EN-450P5 or EN-450T5) had a diameter of 8.5 and 9.3 mm with an operating channel of 2.2 and 2.8 mm, respectively. All of the patients were sedated by propofol with endotracheal intubation. Fluoroscopy was reserved for difficult cases. The depth of insertion into the small bowel was calculated according to the method described by May et al[10]; the advancement of the instrument was measured by counting the number of full 40 cm advancement sequences carried out after the reference point established by an initial full-length insertion of the endoscope. The procedure for enteroscopy via the anal route was different; in this case, the initial introduction was performed via the colon to the ileocecal valve, with or without the balloons. The advancement was measured by counting the number of 40 cm sequences from the ileocecal valve. For the oral route, the endoscopic procedure was performed in the left lateral position, and no bowel preparation was required. For the anal route, four litres of PEG solution was given to the patient the day before the procedure.

Analogous to the Paris classification for gastrointestinal superficial tumours, we treated small bowel lesions according to the endoscopic appearance[15]. A simple snare polypectomy was performed to remove pedunculated polyps, which was the most frequent situation. Endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) was performed for any superficial polypoid sessile tumours or non-polypoid tumours (slightly elevated, flat, and slightly depressed). After the lesion was lifted by a submucosal saline injection, we used a polypectomy snare. EMR was not attempted in ulcerated or excavated lesions because of the risk of invasion depth.

The polyp number and size in each small bowel segment (proximal and distal jejunum and proximal and distal ileum) were documented. Polyp size was estimated using open biopsy forceps. Depending on the polyp size, a submucosal injection of epinephrine-saline solution (1:10000) was delivered before resection. PJS polyps measuring over 10 mm were resected, and the smaller polyps were left in place. It is consensus not to remove small polyps (less than 10 mm) in PJS because the malignant transformation of small bowel polyps in these patients is a rare event[16,17]. Patients with Lynch syndrome, PJS and FAP syndrome received genetic counselling and, if necessary, genetic testing.

For statistical analysis, categorical variables are presented as number (%), and continuous variables are presented as the mean ± one SD or median (25% percentile - 75% percentile). The correlation between the number of diagnosed polyps by CE and DBE was estimated using the Kendall coefficient of concordance (W); the closer the W is to 1, the higher the correlation. To compare the size of the polyps, we considered the first polyp measured at CE or DBE, and the correlation was calculated by an intra-class correlation coefficient (Fleiss formula: two-way mixed model, with a random effect for the subject and a fixed effect for the method). Finally, the agreement between CE and DBE for polyp location was estimated using a weighted kappa. All calculations were performed with the SAS statistical software (version 9.1). Statistical tests were two-sided with an alpha level of 0.05.

From January 2005 to January 2008, 403 enteroscopies were performed at our centre; thirty-two (8%) were performed for small bowel polyps in 25 patients (Table 1). The indications were occult or overt gastrointestinal bleeding (34% and 12%, respectively); PJS, Lynch syndrome or FAP follow-up (31%, 9% and 9%, respectively); and one case of familial liver adenomatosis. Two patients with polyps suspected on CE had a negative DBE; the first of these patients underwent a second CE that did not show any polyps, and the second patient, who had multiple suspected polyps in the ileum based on CE, was diagnosed with lymphoid hyperplasia without polyps on DBE (anal route).

| Patient characteristics | |

| Total | 25 |

| Males | 18 (72) |

| Mean age (yr, range) | 44 (8-83) |

| Only 1 DBE | 20 (80) |

| DBE characteristics | |

| Total | 32 |

| Insertion | |

| Oral route | 26 (81) |

| Anal route | 6 (19) |

| Indications | |

| Occult bleeding | 11 (34) |

| Overt bleeding | 4 (12) |

| Peutz-Jeghers syndrome | 10 (31) |

| Hereditary non-polyposis colon cancer | 3 (9) |

| Familial adenomatous polyposis | 3 (9) |

| Familial liver adenomatosis | 1 (3) |

| Others (abdominal pain) | 3 (9) |

The results of the CE and DBE are summarised in Table 2. CE showed lesions with P1 (11%), P2 (81%) and P3 (8%) imputability (Figure 1). The median number of polyps diagnosed by CE was 1.5 (range: 1-10), and the median size was 30 mm (range: 5-50 mm). The results of the CE determined the route of DBE insertion; the oral route was designated for 26 procedures (81%) in patients with a Gay’s index < 0.75 and anal route was designated for the other patients. No total enteroscopy was possible. The mean total duration of the procedure for the oral and anal routes was 65 min (35-250 min) and 80 min (50-280 min), respectively. The mean polyp size with DBE was 20 mm (8-50 mm) (Figure 2). More than 50% of the polyps were located in the proximal small bowel. Using DBE, we found one small bowel polyp in 22 procedures and more than one in 10 procedures. In total, 31 polypectomies and 12 mucosectomies were performed. Eight polyps were not resected (simple biopsies) because their size was over 5 cm, and two of these polyps appeared as large submucosal lesions.

| Capsule endoscopy n = 27 | Double balloon enteroscopy n = 32 | |

| Median number of polyps | 1.5 (1-10) | 1 (1-13) |

| Mean size (mm) | 30 (5-50) | 20 (8-50) |

| Location | ||

| Proximal jejunum | 17 (63) | 20 (63) |

| Distal jejunum | 4 (15) | 6 (19) |

| Proximal ileum | 6 (22) | 3 (10) |

| Distal ileum | 6 (22) | 4 (12) |

Immediate bleeding occurred in 6 patients, and there was no delayed bleeding. No patient had anticoagulant or antiplatelet therapy before or during the procedure. In 4 cases, there was a large peduncle and a polyp with a size of 30 to 40 mm, which was treated by polypectomy with a snare; two of them were bilobed and ulcerated on the top. Bleeding was stopped using haemostatic clips and a diluted adrenalin injection. In the other 2 cases, the polyps were sessile, measuring 20 to 30 mm. Haemostatic clips stopped the bleeding and closed the EMR wound. For one patient, acute pancreatitis occurred after a long and difficult procedure resulting in the large resection of a polyp located in the distal part of the jejunum (grade D of Balthazar’s classification); this condition resolved within 2 d after medical treatment. There was no mortality related to DBE.

Histological analysis was available for 36 of the 43 polyps (83%) because of an inability to retrieve all of the polyps after resection, especially in the case of multiple polyps. There were 27 hamartomatous polyps (three with low-grade dysplasia), all of which occurred in patients with PJS; six were adenomatous polyps (five with low-grade and one with high-grade dysplasia), and three were lipomas (all were small, ulcerated and responsible for the gastrointestinal bleeding). All of the adenomas polyps were observed in patients with Lynch syndrome or FAP. All the margins were tumor free.

Polyp resection was impossible in 9 patients who underwent surgical treatment with small bowel resection; among these patients, 2 had an ulcerated lesion mimicking a sessile polyp causing bleeding and had surgery as the bleeding failed to stop despite an argon plasma coagulation and adrenalin solution injection. Histological examination of the polyps from these 2 patients showed gastro-intestinal stromal tumour (GIST). For 6 patients, the polyp was larger than 5 cm with difficult enteroscopic positioning, making resection impossible; post-procedure histological examination showed hamartomas in PJS. The remaining patient had more than 10 large polyps, leading to a decision to perform intraoperative enteroscopy.

The agreement between CE and DBE was good for the location and size of polyps with kappa values of 0.90 (95%CI: 0.73-1) and 0.76 (95%CI: 0.43-0.91), respectively, but moderate for the number of polyps (Kendall coefficient value, 0.47, P = 0.0076).

Five treated patients were lost to follow-up. Among the 20 remaining patients, the median follow-up was 14.2 mo (range: 2-36 mo). Another polypectomy was necessary in 4 patients during the follow-up period. Three patients had PJS, and the initial CE showed multiple lesions that could not be removed during one DBE. One patient with PJS had an ileal polypectomy during the first DBE by the anal route. One year later, CE showed a large polyp in the proximal jejunum that was probably not detected on the previous CE. The polyp was resected by DBE using the oral route. For patients with adenoma polyps, one was lost to follow-up; there was no recurrence for the other patients, with a mean follow-up of 26 mo (range: 3-35 mo).

We report 25 patients treated for small bowel polyps by DBE. All of the procedures were well tolerated. The agreement between CE and DBE was good for both the location and size of polyps, but was poor for the number of polyps.

Therapeutic DBE is associated with an incidence of complications of approximately 1%-5%, the most frequent of which are perforation, bleeding and pancreatitis[18,19]. In our series, only 1 case of acute pancreatitis out of 403 enteroscopies occurred, which was rapidly resolved with medication. Episodes of bleeding were successfully treated during DBE with an injection of epinephrine-saline solution and clips. In a recent study describing complications after DBE[19], the perforation rate was 1.5% per polyp (2 among 137 polyps removed) and 2.9% per patient (2 among 68 patients). In their series of 79 polyps in 15 patients with PJS, Gao et al[20] reported no perforation after polyp removal, and we observed the same results. The majority of the removed polyps in our series were pedunculated, and all sessile polyps had a good elevation after serum sub-mucosa injection. Good exposure of the polyp is very important in the case of large polyp size because of a higher risk of perforation. The change in position of the patient (left lateral or supine position) can reduce this risk during resection. We believe that polyp resection should not be attempt when there is no lifting sign or when the appearance is a sub-mucosal lesion.

In our series, most of the polyps were localised to the proximal region of the jejunum, and some of the polyps were nearly 5 centimetres in size. The polyp location shown on CE was used to indicate whether the DBE route should be oral or anal using Gay’s Index. Moreover, when CE showed a large polyp, it was possible to predict the resection difficulty and the duration of the procedure. The moderate correlation between CE and DBE count is probably due to DBE distension of the small bowel by air insufflation in the case of numerous polyps, which provided a more accurate way of counting a larger number of small polyps compared to CE. In studies addressing the same issue, Marmo et al[21] showed that CE and DBE show good agreement for vascular and inflammatory lesions, but not for polyps or neoplasia. In this study, in concordance for the polyp size, the number or the location of the polyp was not analysed separately.

In our study, 10 patients had PJS. This high number of PJS can be explained by the presence of a genetics unit in our centre that treats patients with gastrointestinal polyposis. Several studies have shown that polypectomy during DBE is effective and may decrease the need for urgent laparotomy for occlusion due to a large polyp. Chen et al[22] showed that a total of 17 enteroscopies resulted in polypectomy in six patients with PJS without complications. All patients underwent complete small bowel exploration in 1 or 2 steps. Another technique that allows for small bowel polypectomy is intraoperative enteroscopy, but DBE is less invasive and more convenient for the patient[23].

The screening and management of small bowel polyps and tumours is important for patients with familial and non-familial polyposis syndromes. Mönkemüller et al[24] studied the usefulness of DBE-assisted chromoendoscopy for the detection and characterisation of small bowel polyps in patients with FAP; jejunal polyps were detected in 67% of the patients, and chromoendoscopy helped detect additional polyps in two patients.

The second most frequent and most important site, after the colon, of adenomas in FAP is the duodenum. The three patients in our study were stage I or II according to the Spigelman score (between 5 and 20 polyps, measuring between 1 and 10 mm, tubular and without high-grade dysplasia).

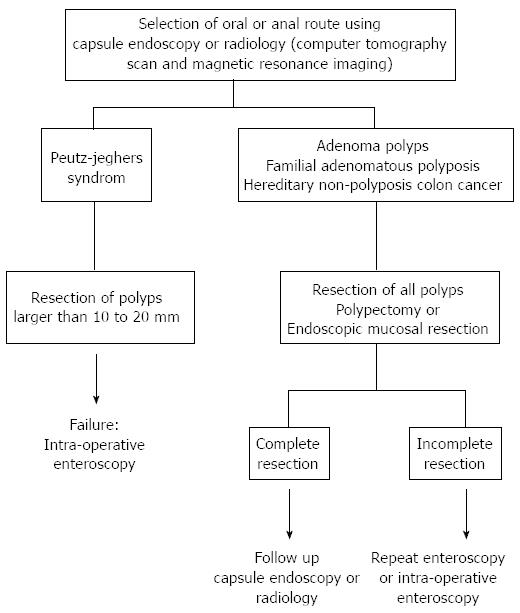

Our study has the potential limitation of being a single-centre retrospective study in a university setting with an associated recruitment bias. However, to our knowledge, this is one of the largest endoscopic series focusing on the diagnosis and management of small bowel polyps excluding tumours. Another criticism could be that our patient sample has been selected based on a positive CE, which can lead to an optimistic estimation of agreement because these patients are not taken into account for kappa calculation. However, any missed patients probably harbour small lesions, and their absence from our sample probably has no influence on our estimation of the complication rate. Another limitation is the lack of complete small bowel exploration. Sakamoto et al[25] showed that several sessions of enteroscopy in PJS patients with resection of polyps more than 20 mm in size was useful for reducing polyp size and number, preventing intussusceptions, and avoiding laparotomy. In our study is the use of the first small-bowel CE device PillCam™ SB (Given imaging, Yoqneam, israel). Actually, improvements have been made as the PillCam™ SB2, and new capsules were developed: EndoCapsule™ (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan), MiroCam™ (introMedic Co., seoul, South Korea) and OMOM capsule endoscope (Jianshan Science and Technology Group Co., Ltd., Chongqing, China)[26-28]. Advantages are deeper field of view (up to 156°), higher frame rate (3 per second for MiroCam™), longer battery life (over 11 h) and the possibility of real-time image acquisition. With the OMOM capsule, the frame rate can be changed during the study. All these improvements allow a better visualization of the intestinal mucosa and may help for polyps’ detection. In Figure 3, we have summarized our endoscopic strategy for small bowel polyp resection in PJS patients and in adenoma polyps in patients with Lynch syndrome and FAP. For patients with FAP, the resection of small bowel polyps should be always attempted because of the potential risk of progression to adenocarcinoma. For those suffering from PJS syndrome, we suggest to remove only larger polyps more than 10 mm, since the major risk is bleeding and intussusception. Follow-up by CE or DBE should be recommended after the removal of adenomatous or hamartomatous polyps, but future studies have to determine which interval should be chosen for the follow-up.

In summary, DBE is a safe and effective technique for diagnosing and resecting most polyps in the small bowel with a low complication rate. However, it is a time-consuming procedure that is not always capable of visualising the entire small bowel and should be preceded by CE witch is a less invasive technique. CE allows to show the number, location and size of the polyps and thus, indicate the route (i.e., oral or anal) and predict the difficulty of the polypectomy during optical enteroscopy.

We thank Severine Peyrard for her expert statistical advice.

Capsule endoscopy (CE), after being ingested by the patient, allows entire small bowel exploration. Double balloon enteroscopy (DBE) is an overtube-assisted endoscopic technique which allows deep exploration of the small bowel and resection of polyps diagnosed by CE. Polyps must be resected because of the risk of malignant transformation and/or the risk of small bowel obstruction.

Endoscopic techniques, as DBE, allow mini-invasive treatment for small bowel polyps as an alternative to surgery.

DBE is a safe and effective technique for diagnosing and resecting most polyps in the small bowel with a low complication rate. CE allows to show the number, location and size of the polyps and thus, indicate the route (i.e., oral or anal) and predict the difficulty of the polypectomy during optical enteroscopy.

Any patient with suspected small bowel disease should be eligible to an endoscopic small bowel exploration by DBE and CE.

Enteroscopy: endoscopic exploration of small bowel; Polypectomy: polyp’s resection.

This study demonstrates the utility of C followed by DBE to better care for patients with small bowel polyps.

P- Reviewer Murphy SJ S- Editor Song XX L- Editor A E- Editor Zhang DN

| 1. | Yamamoto H, Kita H, Sunada K, Hayashi Y, Sato H, Yano T, Iwamoto M, Sekine Y, Miyata T, Kuno A. Clinical outcomes of double-balloon endoscopy for the diagnosis and treatment of small-intestinal diseases. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;2:1010-1016. |

| 2. | Cellier C. Obscure gastrointestinal bleeding: role of videocapsule and double-balloon enteroscopy. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2008;22:329-340. |

| 3. | Heine GD, Hadithi M, Groenen MJ, Kuipers EJ, Jacobs MA, Mulder CJ. Double-balloon enteroscopy: indications, diagnostic yield, and complications in a series of 275 patients with suspected small-bowel disease. Endoscopy. 2006;38:42-48. |

| 4. | Di Caro S, May A, Heine DG, Fini L, Landi B, Petruzziello L, Cellier C, Mulder CJ, Costamagna G, Ell C. The European experience with double-balloon enteroscopy: indications, methodology, safety, and clinical impact. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;62:545-550. |

| 5. | Mönkemüller K, Weigt J, Treiber G, Kolfenbach S, Kahl S, Röcken C, Ebert M, Fry LC, Malfertheiner P. Diagnostic and therapeutic impact of double-balloon enteroscopy. Endoscopy. 2006;38:67-72. |

| 6. | Yamamoto H, Yano T, Kita H, Sunada K, Ido K, Sugano K. New system of double-balloon enteroscopy for diagnosis and treatment of small intestinal disorders. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:1556; author reply 1556-1557. |

| 7. | May A, Nachbar L, Wardak A, Yamamoto H, Ell C. Double-balloon enteroscopy: preliminary experience in patients with obscure gastrointestinal bleeding or chronic abdominal pain. Endoscopy. 2003;35:985-991. |

| 8. | Ell C, May A, Nachbar L, Cellier C, Landi B, di Caro S, Gasbarrini A. Push-and-pull enteroscopy in the small bowel using the double-balloon technique: results of a prospective European multicenter study. Endoscopy. 2005;37:613-616. |

| 9. | Matsumoto T, Moriyama T, Esaki M, Nakamura S, Iida M. Performance of antegrade double-balloon enteroscopy: comparison with push enteroscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;62:392-398. |

| 10. | May A, Nachbar L, Schneider M, Neumann M, Ell C. Push-and-pull enteroscopy using the double-balloon technique: method of assessing depth of insertion and training of the enteroscopy technique using the Erlangen Endo-Trainer. Endoscopy. 2005;37:66-70. |

| 11. | Schulmann K, Hollerbach S, Kraus K, Willert J, Vogel T, Möslein G, Pox C, Reiser M, Reinacher-Schick A, Schmiegel W. Value of capsule endoscopy for the detection of small bowel polyps in patients with hereditary polyposis syndromes (FAP, PJS, FJP). Gastroenterology. 2003;124:A-550. |

| 12. | Rodriguez-Bigas MA, Penetrante RB, Herrera L, Petrelli NJ. Intraoperative small bowel enteroscopy in familial adenomatous and familial juvenile polyposis. Gastrointest Endosc. 1995;42:560-564. |

| 13. | Saurin JC, Delvaux M, Gaudin JL, Fassler I, Villarejo J, Vahedi K, Bitoun A, Canard JM, Souquet JC, Ponchon T. Diagnostic value of endoscopic capsule in patients with obscure digestive bleeding: blinded comparison with video push-enteroscopy. Endoscopy. 2003;35:576-584. |

| 14. | Gay G, Delvaux M, Fassler I. Outcome of capsule endoscopy in determining indication and route for push-and-pull enteroscopy. Endoscopy. 2006;38:49-58. |

| 15. | The Paris endoscopic classification of superficial neoplastic lesions: esophagus, stomach, and colon: November 30 to December 1, 2002. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;58:S3-43. |

| 16. | Westerman AM, Entius MM, de Baar E, Boor PP, Koole R, van Velthuysen ML, Offerhaus GJ, Lindhout D, de Rooij FW, Wilson JH. Peutz-Jeghers syndrome: 78-year follow-up of the original family. Lancet. 1999;353:1211-1215. |

| 17. | Plum N, May AD, Manner H, Ell C. [Peutz-Jeghers syndrome: endoscopic detection and treatment of small bowel polyps by double-balloon enteroscopy]. Z Gastroenterol. 2007;45:1049-1055. |

| 18. | Mensink PB, Haringsma J, Kucharzik T, Cellier C, Pérez-Cuadrado E, Mönkemüller K, Gasbarrini A, Kaffes AJ, Nakamura K, Yen HH. Complications of double balloon enteroscopy: a multicenter survey. Endoscopy. 2007;39:613-615. |

| 19. | Möschler O, May A, Müller MK, Ell C. Complications in and performance of double-balloon enteroscopy (DBE): results from a large prospective DBE database in Germany. Endoscopy. 2011;43:484-489. |

| 20. | Gao H, van Lier MG, Poley JW, Kuipers EJ, van Leerdam ME, Mensink PB. Endoscopic therapy of small-bowel polyps by double-balloon enteroscopy in patients with Peutz-Jeghers syndrome. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;71:768-773. |

| 21. | Marmo R, Rotondano G, Casetti T, Manes G, Chilovi F, Sprujevnik T, Bianco MA, Brancaccio ML, Imbesi V, Benvenuti S. Degree of concordance between double-balloon enteroscopy and capsule endoscopy in obscure gastrointestinal bleeding: a multicenter study. Endoscopy. 2009;41:587-592. |

| 22. | Chen TH, Lin WP, Su MY, Hsu CM, Chiu CT, Chen PC, Kong MS, Lai MW, Yeh TS. Balloon-assisted enteroscopy with prophylactic polypectomy for Peutz-Jeghers syndrome: experience in Taiwan. Dig Dis Sci. 2011;56:1472-1475. |

| 23. | Kopácová M, Bures J, Ferko A, Tachecí I, Rejchrt S. Comparison of intraoperative enteroscopy and double-balloon enteroscopy for the diagnosis and treatment of Peutz-Jeghers syndrome. Surg Endosc. 2010;24:1904-1910. |

| 24. | Mönkemüller K, Fry LC, Ebert M, Bellutti M, Venerito M, Knippig C, Rickes S, Muschke P, Röcken C, Malfertheiner P. Feasibility of double-balloon enteroscopy-assisted chromoendoscopy of the small bowel in patients with familial adenomatous polyposis. Endoscopy. 2007;39:52-57. |

| 25. | Sakamoto H, Yamamoto H, Hayashi Y, Yano T, Miyata T, Nishimura N, Shinhata H, Sato H, Sunada K, Sugano K. Nonsurgical management of small-bowel polyps in Peutz-Jeghers syndrome with extensive polypectomy by using double-balloon endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;74:328-333. |

| 26. | Moglia A, Menciassi A, Dario P, Cuschieri A. Capsule endoscopy: progress update and challenges ahead. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;6:353-362. |

| 27. | Liao Z, Gao R, Li F, Xu C, Zhou Y, Wang JS, Li ZS. Fields of applications, diagnostic yields and findings of OMOM capsule endoscopy in 2400 Chinese patients. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:2669-2676. |

| 28. | Koulaouzidis A, Smirnidis A, Douglas S, Plevris JN. QuickView in small-bowel capsule endoscopy is useful in certain clinical settings, but QuickView with Blue Mode is of no additional benefit. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;24:1099-1104. |