INTRODUCTION

Portal hypertension is a common clinical syndrome, defined by a pathologic increase in the portal venous pressure, in which the hepatic venous pressure gradient (HVPG) is increased above normal values (1-5 mmHg). In cirrhosis, portal hypertension results from the combination of increased intrahepatic vascular resistance and increased blood flow through the portal venous system. When the HVPG rises above 10 mmHg, complications of portal hypertension can arise. Therefore, this value represents the threshold for defining portal hypertension as being clinically significant and plays a crucial role in the transition from the preclinical to the clinical phase of the disease[1-3].

The importance of this syndrome is characterized by the frequency and severity of complications, such as massive upper gastrointestinal bleeding from ruptured gastroesophageal varices and portal hypertensive gastropathy, ascites, hepatorenal syndrome and hepatic encephalopathy[4]. These complications are major causes of death and the main indications for liver transplantation in patients with cirrhosis.

CLINICAL COURSE OF VARICEAL BLEEDING

Portal hypertension causes the development of portosystemic collaterals, among which esophageal and gastric varices are the most relevant[5]. Their rupture can result in variceal hemorrhage, which is one the most lethal complications of cirrhosis.

Prospective studies have shown that more than 90% of cirrhotic patients develop esophageal varices sometime in their lifetime and 30% of these will bleed. When cirrhosis is diagnosed, varices are present in about 30%-40% of compensated patients and 60% of those who present ascites[6]. After initial diagnosis of cirrhosis, the expected incidence of newly developed varices is about 5% per year[7-11].

Once developed, varices increase in size from small to large before they eventually rupture and bleed. Studies assessing the progression from small to large varices are controversial, showing the rates of progression of varices ranging from 5% to 30% per year[8,10-13]. The most likely reason for such variability is the different selection of patients and follow-up endoscopic schedule across studies[14]. Moreover, inter- observer variability also accounts for differences in the reported rates of development of varices. Decompensated cirrhosis (Child B/C), alcoholic etiology of cirrhosis, HVPG and the presence of red wale markings in the esophageal varices at the time of baseline endoscopy are the main factors associated with the progression from small to large varices[8,12,15].

Once varices have been diagnosed, the overall annual incidence of variceal bleeding accounts for 10%-15% in non-selected patients[16,17]. The most important predictive factors are variceal size, severity of liver dysfunction defined by the Child-Pugh classification and red wale markings[17]. These risk indicators have been combined in the North Italian Endoscopy Club (NIEC) index, which allows the classifications of patients into different groups with a predicted 1-year bleeding risk. According to the NIEC index, patients with small varices and advanced liver insufficiency carry a considerable risk of first bleeding. The estimated probability of bleeding within 1 year in Child-Pugh class A patients with large varices and red signs is 24%, compared with 20% for Child-Pugh C patients with small varices and no red signs. Overall, variceal size remains the most useful predictor for variceal bleeding[18]. The risk of bleeding is very low (1%-2%) in patients without varices at the first examination, and increases to 5% per year in those with small varices, and to 15% per year in those with medium or large varices at diagnosis[10,11]. Other predictors of variceal first bleeding are the presence of red signs. Variceal size and red color signs are associated with an increased bleeding risk probably because they reflect direct parameters determining variceal wall tension (radius, wall thickness), which is the decisive factor determining variceal rupture[19,20]. In addition, many studies have shown that variceal bleeding only occurs if the HVPG reaches a threshold value of 12 mmHg. Conversely, if the HVPG is substantially reduced (below 12 mmHg or by > 20% of the baseline levels), there is a marked reduction not only in the risk of bleeding, but in the risk of developing ascites, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis[21] and death.

Variceal bleeding is the most severe complication of cirrhosis and is the second most common cause of mortality among the patients[22]. In patients with cirrhosis, ruptured esophageal varices cause approximately 70% of all upper digestive bleeding[23]. Mortality from variceal bleeding has greatly decreased in the last two decades from 42% in the Graham and Smith study in 1981[24] to the actual rates that range 6-12%[10,25]. This decrease results from the implementation of effective treatment options, such as endoscopic and pharmacological therapies and transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS), as well as improved general medical care. The general consensus is that any death occurring within 6 wk from hospital admission for variceal bleeding should be considered as a bleeding-related death[26]. Immediate mortality from uncontrolled bleeding ranges from 4% to 8%[9,27-29]. Prehospital mortality from variceal bleeding is around 3%[30]. Nowadays, the patients die due to infection, kidney failure, hepaticencephalopathy, early rebleeding, or uncontrolled bleeding in the first weeks after an initial episode. The first three ones are the most important late prognostic markers after the first episode of bleeding[31]. Factors independently associated with a higher mortality are poor liver function, severe portal hypertension with HVPG > 20 mmHg, and active bleeding at endoscopy[32,33]

The natural history of esophageal varices in Non-Cirrhotic Portal Hypertension (NCPH) is not known. Progression of variceal size occurs at a rate of 10%-15% per year in patients with cirrhosis, mostly dependent on liver dysfunction. Such a progression of varices in NCPH is less likely to occur, as the liver function continues to be normal. Similarly, a decrease in the size of esophageal varices, as seen in patients with cirrhosis with an improvement in liver function, is unlikely in NCPH[34-37].

ENDOSCOPIC MANAGEMENT OF ESOPHAGEAL VARICES

Endoscopic therapies for varices aim to reduce variceal wall tension by obliteration of the varix. The two principal methods available for esophageal varices are endoscopic sclerotherapy (EST) and band ligation (EBL). Endoscopic therapy is a local treatment that has no effect on the pathophysiological mechanisms that lead to portal hypertension and variceal rupture. However, a spontaneous decrease in HVPG occurs in around 30% of patients treated with either EST or EBL to prevent variceal rebleeding[38,39]. It has been shown that patients with such a spontaneous hemodynamic response require fewer sessions of endoscopic therapy until variceal obliteration, and have a higher rate of variceal eradication than patients treated with endoscopic methods who have no spontaneous response[38,39]. Furthermore, spontaneous responders have a significantly lower probability of rebleeding and better survival. These data suggest that adding beta-blockers to endoscopic therapy may enhance the efficacy of treatment by increasing the rate of hemodynamic responders[39,40]

SCLEROTHERAPY

Endoscopic injection sclerotherapy has been used to treat variceal hemorrhage for about 50 years. Endoscopic treatment of bleeding esophageal varices was originally described by Crafood and Frenckner in 1939[41], though the technique was not widely adopted until the 1970s. In the 1980s, flexible endoscopic sclerotherapy replaced the methods that used rigid endoscopes, and rapid progress has been made in the techniques since then[42]. As a result, survival of patients with hemorrhage from esophageal varices has greatly improved in the last 30 years[43-45]. Subsequently, some sclerosants such as sodium morrhuate, podidocanol, ethanolamine, alcohol, and sodium tetradecyl sulfate have been widely used. Actually, the most commonly used agents are ethanolamine oleate (5%) or polidocanol (1%-2%) in Europe, and sodium morrhuate (5%) in the United States[39,46]. All these sclerosing agents have been used successfully in controlled trials[47]. Although some studies tried to compare the effectiveness between different sclerosants[48], it is difficult to draw a final conclusion.

EST consists of the injection of a sclerosing agent into the variceal lumen or adjacent to the varix, with flexible catheter with a needle tip, inducing thrombosis of the vessel and inflammation of the surrounding tissues[49,50]. During active bleeding, sclerotherapy may achieve hemostasis, inducing variceal thrombosis and external compression by tissue edema. With repeated sessions, the inflammation of the vascular wall and surrounding tissues leads to fibrosis, resulting in variceal obliteration[51]. Furthermore, vascular thrombosis may induce ulcers that also heal, inducing fibrosis. There are technical variations in performing EST, such as type and concentration of the sclerosants, volume injected, interval between sessions, and number of sessions[47]. Some endoscopists use free-hand injections, others prefer to incorporate a balloon onto the distal end of the endoscope to compress the varices following injections[52,53]. The optimal dose of sclerosants is also unknown. The sclerosants can be injected either intravariceally or paravariceally[29]. Paravariceal injection using a large volume of polidocanol, in mediately adjacent and slightly distal to the bleeding point, forms a protective fibrosis layer around varices. Intravariceal injection, directly induces variceal thrombosis. The first injection of 1-3 mL of the sclerosant should be administrated right below the bleeding site. Afterwards, 2-3 mL injections are administrated to the remaining varices adjacent to the bleeding varix. The main objective is to target the lower esophagus near the gastroesophageal (GE) junction. Up to 10-15 mL of a sclerosant solution may be used in the session. In the acute setting, the paravariceal injection cannot be easily accomplished because of the ongoing bleeding and it is mostly reserved for elective sclerotherapy[29,54].

The advantages of EST are that it is cheap and easy to use, the injection catheter fits through the working channel of a diagnostic gastroscope, it can be quickly assembled, and does not require a second oral intubation. Additionally, there is a rapid thrombosis.

However, several local and systemic complications may arise after EST[52,55-58]. The reported frequency of complications of sclerotherapy varies greatly between series and is critically related to the experience of operators and the frequency and completeness of follow-up examinations. Minor complications occurring within the first 24-48 h and not requiring treatment, such as low-grade fever, retrosternal chest pain, temporary dysphagia, asymptomatic pleural effusions, and other nonspecific transient chest radiographic changes, are very common[49].

The complications can be classified as local: esophageal ulcers, ulcer bleeding, and esophageal stricture; cardiovascular and respiratory: pleural effusion, adult respiratory distress syndrome, and pericarditis; and systemic: fever, bacteremia, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, distant embolism, and distant abscess[53]. It is impossible to predict what kind of complications may be encountered in patients receiving EST.

Among them, bacteremia, post-sclerotherapy esophageal ulcer bleeding, and stricture are the most frequent adverse events[52,55-58]. The main cause of these hazardous complications is usually an extensive wall necrosis induced by an incorrect injection technique, too much sclerosant being injected, or a high concentration of the sclerosant[59]. Esophageal ulcers are common and they may cause bleeding in 20% of patients[60,61]. Mucosal ulceration is the most common esophageal complication, occurring in up to 90% of patients within 24 h of injection and heals rapidly in most cases. Many authors question whether ulceration should be regarded as a complication or, rather, as a desired effect of sclerotherapy, because the development of scar tissue after ulceration helps obliterate varices[62]. Nevertheless, ulcerated variceal columns found at follow-up endoscopy should not be injected. The usefulness of sucralfate in healing esophageal ulcers and preventing rebleeding is controversial[63]. They usually heal with omeprazole. Bacteremia may occur in up to 35% and lead to other complications, such as spontaneous bacterial peritonitis or distal abscesses[64,65]. Esophageal stenoses have been reported with a frequency varying between 2% and 10%. Esophageal perforation is a rare, but severe complication that may occur either by direct traumatic rupture or by full-thickness esophageal wall necrosis secondary to excessive injection of sclerosant. The former presents shortly after the procedure and may be accompanied by subcutaneous emphysema, whereas the latter may produce insidious symptoms over a few days before free perforation becomes manifest[49].

Mortality directly resulting from post-EST complications may be noted in 2% of patients and it commonly results from the major complications of recurrent bleeding, perforation, sepsis, and respiratory disorders[55]

ENDOSCOPIC VARICEAL LIGATION

In 1989, Stiegmann and Goff[66] introduced the application of endoscopic variceal ligation (EVL) to treat esophageal varices. In contrast to the use of chemical action induced by EST, EVL obliterates varices by causing mechanical strangulation with rubber bands. The technique is an adaptation of that applied to banding ligation of internal hemorrhoids. Owing to its action on the suctioned, entrapped varices, the main reaction is usually limited over the superficial esophageal mucosa.

EVL consists of the placement of rubber rings on variceal columns which are sucked into a plastic hollow cylinder attached to the tip of the endoscope[67]. Multiple-shot devices have largely replaced the original single-shot ligators, since the procedure is much simpler and faster with multishot devices, and an overtube is not required, thus avoiding the severe complications related to its use. Furthermore, new transparent caps are available which improve the visibility (visibility with the old caps may be reduced by 30%)[39]. Several commercial multiband devices are available for EBL. They have 4-10 preloaded bands. All have the same principle. i.e., placement of elastic bands on a varix after it is sucked into a clear plastic cylinder attached to the tip of the endoscope[54].

After the diagnostic endoscopy is performed and the culprit varix identified and its distance measured to the mouth, the endoscope is withdrawn and the ligation device is loaded[54]. The device is firmly attached to the scope and placed in a neutral mode. Sometimes passing the endoscope with the loading device may be tricky. This requires slight flexion of the neck, gentle and constant advancement of the scope with visualization of the pharynx, and a slight torque of the shaft left and right[54]. After intubation, the device is placed in ‘‘forward only’’ mode. Once the varix is identified, the tip is pointed toward it and continuous suction applied so it can fill the cap. This requires smooth movement right and left. Once inside the cap, a ‘‘red out’’ sign should appear and at this point the band can be fired[54]. Usually the procedure is performed by starting the application of the bands at the gastroesophageal junction and working upwards in a helical fashion to avoid circumferential placement of bands at the same level[49]. The application of bands progresses for approximately 6-8 cm within the palisade and perforating zones[53].

In the setting of an active bleed, the restricted field of vision caused by the cylinder attachment makes the technique difficult to perform and this requires active flushing with water and suction as necessary. Ideally, the rubber band should be delivered on the varix at the point of bleeding site but if missed, banding of mucosa is not harmful in contrast to injecting a sclerosant, which may cause side effects. If, however the point of bleeding cannot be identified, a multiple banding device can be used to place several bands at the GE junction, provided that no subcardial prolongation occurs, which may reduce torrential bleeding, and further bands can be fired afterward[54,59].

After the application of rubber bands over esophageal varices, the ligated tissues with rubber bands may fall off within a few days (range: 1-10 d). Following the sloughing of varices, shallow esophageal ulcers are ubiquitous at ligated sites and esophageal varices become smaller in diameter. The ligation induced-ulcers are shallower, have a greater surface area, and heal more rapidly than those caused by EST[53,68]. Patients should start with liquids for the first 12 h and then take soft foods gradually. A recent controlled trial demonstrates that subjects who received pantoprazole after elective EVL had significantly smaller post-banding ulcers on follow-up endoscopy than subjects who received placebo. However, the total ulcer number and patient symptoms were not different between the groups[69].

Eradication of varices usually requires two to four EVL sessions[39]. In a meta-analysis including 13 articles performed in 1999 by de Franchis and Primignani[49], the mean number of sessions required to achieve variceal obliteration was reduced from 3.6 in patients receiving EVL to 5.4 in patients receiving ETS. Both the optimal number of bands placed in each session and the optimal time interval between sessions should be clarified to improve the efficacy of this treatment. Usually varices are considered eradicated when they have either disappeared or cannot be grasped and banded by the ligator[39]. Variceal eradication is obtained in about 90% of patients, although recurrence is not uncommon[70]. The main disadvantage of EVL is possibly a higher frequency of recurrent varices[71-73]. Fortunately, those recurrent varices can usually be treated with repeated ligation[73]. Moreover, the recurrence after EVL did not lead to a higher risk of rebleeding or require more endoscopic treatments[53]. The optimal surveillance program should also be established. A study from Japan demonstrated that EVL performed once every 2 mo was better than EVL performed once every 2 wk regarding overall rates of variceal recurrence[74]. Because the rebleeding rate of patients receiving endoscopic therapy could only be significantly reduced in those who achieve variceal obliteration within a short period, EVL performed at an interval of 2 mo in the prevention of variceal rebleeding may be inappropriate. In our clinical pathway, sessions are scheduled at a 4-week interval to achieve variceal eradication[29].

EBL was developed as an alternative, with fewer complications than EST, for the treatment of esophageal varices. The complications of EVL include esophageal laceration or perforation (mostly due to trauma of the overtube), transient dysphagia, retrosternal pain, esophageal stricture, transient accentuation of portal hypertensive gastropathy, ulcer bleeding, and bacteremia[75]. The incidence of bacteremia and infectious sequelae after EIS was 5-10 times higher than after EVL[76].

OTHER TECHNIQUES

Argon plasma coagulation has also been combined with EVL to prevent variceal recurrence. Recently, Harras et al[77] conducted a randomized trial and they established that band ligation plus argon plasmacoagulation allows for very rapid eradication of varices, and a low recurrence rate, with no obvious recorded complications, but it has the disadvantage of being the most expensive technique and requires special equipment that is only available in a few endoscopic centers.

Endoscopic clipping has been rarely guided in the management of bleeding varices. In 2003, Yol et al[78,79] carried out a controlled trial to evaluate the effectiveness of endoscopic clipping in the hemostasis of bleeding esophageal varices and the eventual variceal eradication was compared with that of band ligation in patients with bleeding from esophageal varices. They concluded that it results in a high initial hemostasis rate, a decreased risk of rebleeding, and fewer treatment sessions needed for variceal eradication.

The tissue adhesives n-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate (Histoacryl) and isobutyl-2-cyanoacrylate (Bucrylate) have been used to treat esophageal and gastric varices[80-82]. When injected into esophageal or gastric varices, almost immediate obliteration of the vessel was achieved. The polymerization does not depend on clotting factors. The adhesives harden within seconds of coming into contact with a physiologic milieu, forming a solid cast of the injected vessel. Thus, their injection, if executed correctly, should result in almost immediate control of bleeding as the lumen of the varix is occluded. The rapid hardening of the adhesives makes their application less simple than that of conventional sclerosants. The technique requires care to ensure that the adhesive does not come into contact with the endoscope because this might result in permanent damage to the working channel of the instrument. This risk can be minimized by applying silicone oil to the tip of the endoscope and by mixing the adhesive with a radiographic contrast agent (Lipiodol) in a ratio of 1:1 to delay the premature hardening that it occurs after 20 s[49,81]. Once correct placement has been confirmed, the tissue adhesive is injected in small aliquots of a maximum of 0.5 mL for esophageal varices and 1 mL for gastric varices. The injection of tissue adhesive differs from conventional sclerotherapy in that the injection must be strictly intravariceal. There is no consensus on the cyanoacrylate injection (CI) technique, with major variations in relation to the proportion and volume of cyanoacrylate and Lipiodol solution to be injected[83,84]. Several weeks later (2 wk to 3 mo) the overlying mucosa sloughs off and a glue cast is extruded into the lumen of the gastrointestinal tract. The ulceration subsequently reepithelialises. There are several randomized controlled trials comparing use of cyanocrilate with other therapies for treatment of esophageal varices. Evrard et al[85] compared CI in esophageal varices with B-blocker as secondary prophylaxis for variceal bleeding and concluded that the CI group had more complications. Another study compared CI with EVL in the treatment of variceal bleeding and variceal eradication. Despite a comparable initial success in acute bleeding control, EVL was superior to CI in the subsequent management of EVL[86]. Moreover, recently Santos et al[87] observed that no significant differences between the EVL and CI groups were observed in the treatment of EV inpatients with advanced liver disease regarding mortality, variceal eradication, and rates of major complications. However, minor complications and variceal recurrence were significantly more common in the CI group. In addition, there was a clear trend toward more bleeding episodes in patients included in the CI group. Based on these studies, further controlled studies are needed to recommend the injection as first-line therapy for both acute episodes and in primary and secondary prophylaxis. Complications associated with injection of cyanoacrylate glue for treatment of bleeding lesions include embolic events and equipment damage. Life threatening complications have included episodes of abdominal, pulmonary, and intracerebral embolization and infarction.

Also, detachable nylon mini-loops have been tested as an alternative for endoscopic band ligation to treat both esophageal[88,89] and gastric varices. As with band ligation, a detachable nylon ring (mini-loop), with a maximum diameter of 11 mm, passed through the accessory channel of a standard endoscope is opened at the rim of a transparent ligation chamber attached to the instrument. By suction, a varix is brought into the chamber, the mini-loop is maneuvered over the varix, closed, and detached[49]. The procedure can be repeated several times, and multiple varices can be thus ligated with a single insertion of the endoscope. Although in 1999 Shim and colleagues demonstrated similar efficacy against EVL endoloop, this technique is now obsolete due to the superiority of EVL[90].

UTILITY OF THERAPEUTIC ENDOSCOPY IN DIFFERENT CLINICAL SITUATIONS OF ACUTE BLEEDING

Both sclerotherapy and band ligation have shown to be effective in the control of acute variceal bleeding, however EVL has become the treatment of choice for both controlling variceal hemorrhage and variceal obliteration in secondary prophylaxis.

Two meta-analyses by Franchis and Primignani[49] and Laine[91] showed that EVL is better than sclerotherapy in the initial control of bleeding, prevention of rebleeding, and is associated with less adverse events (including ulceration and stricture formation) and improved mortality. Additionally, sclerotherapy, but not EVL, may induce a sustained increase in portal pressure[92]. Therefore, EVL should be the endoscopic therapy of choice in acute variceal bleeding, though injection sclerotherapy is acceptable if band ligation is not available or technically difficult[26]. The combination of EST and EVL does not appear to be better than EVL alone[93]. Endoscopic therapy can be performed at the time of diagnostic endoscopy, early after admission, provided that a skilled endoscopist is available. In our experience, when there is severe active bleeding, we normally use the EST, because the EVL is technically more difficult. However, when there are white nipple signs or hematocystic spots, we proceed with EVL[29].

Drug therapy (terlipressin or somatostatin) also improves the results of endoscopic treatment if started before or just after sclerotherapy or band ligation[94-97]. Vice versa, the endoscopic therapy also improves the efficacy of vasoactive treatment[94]. However, this combined approach failed to significantly improve the 6-wk mortality with respect to endoscopic therapy or a vasoactive drug[94] alone[98,99].

The current recommendation is to combine the two approaches, start vasoactive drug therapy early (ideally during the transferal to the hospital, even if active bleeding is suspected) during 5 d and perform EVL (or injection sclerotherapy if band ligation is technically difficult) after initial resuscitation when the patient is stable and bleeding has ceased or slowed[26,98].

PRIMARY PROPHYLAXIS OF ESOPHAGEAL VARICEAL BLEEDING

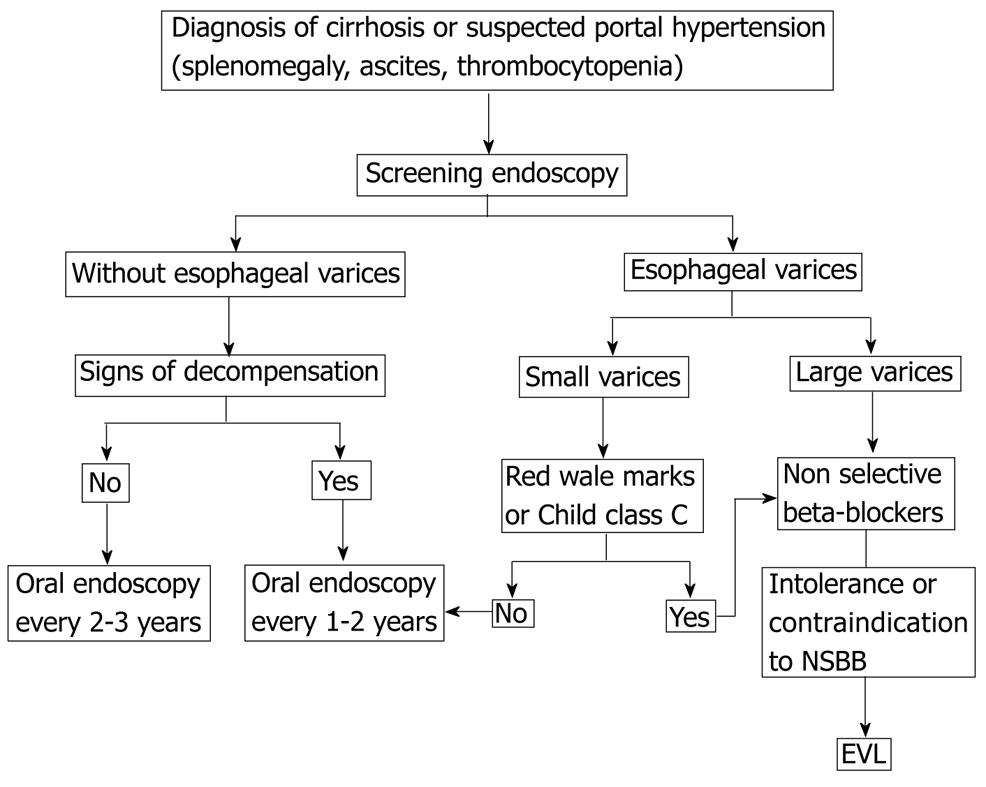

So far, there has been no reliable method for predicting which cirrhotic patients will have esophageal varices without endoscopy[100]. None of the above noninvasive methods is accurate enough to completely discard the presence of esophageal varices when noninvasive indicators are negative. Thus, the current recommendation is that all patients, at the time of initial diagnosis of cirrhosis, should undergo an endoscopy for the screening of esophageal varices[101].

The optimal surveillance intervals for esophageal varices have not yet been determined. In patients without varices on initial endoscopy, repeated endoscopies at 2-3 year intervals have been suggested to detect the development of varices before bleeding occurs[102]. In the centers where hepatic hemodynamic studies are available, it is advisable to measure HVPG. This interval should be decreased in patients who have an initial HVPG 10 mmHg. In patients with small varices on initial endoscopy, the aim of subsequent evaluations is to detect the progression of small to large varices because of the important prognostic and therapeutic implications. Based on the yearly progression rates of 5%-20% (a median of 12%) in the prospective studies, endoscopy should be repeated every 1-2 years[102]. In patients with advanced cirrhosis, red wale marks or alcoholic cirrhosis, a 1-year interval might be recommended. Once the patient is started on beta-adrenergic blockers, there is no need for further endoscopic surveillance.

Because of the high mortality rate associated with the initial variceal hemorrhage, primary prevention is indicated. In patients with small varices that are associated with a high risk of hemorrhage (varices with red wale marks or varices in a patient with Child class C disease), nonselective beta-blockers are recommended[26]. Patients with small varices without signs of increased risk may be treated with non-selective beta-blockers (NSBB) to prevent progression of varices and bleeding. Further studies are required to confirm their benefit[26].

In patients with medium or large varices, either nonselective beta-blockers or endoscopic variceal ligation can be used, since a meta-analysis of high-quality, randomized, controlled trials has shown equivalent efficacy and no differences in survival[103]. EST is not recommended for primary prophylaxis[55]. Meta-analysis consistently show a significantly lower incidence of first upper gastrointestinal bleeding and variceal bleeding with ligation vs beta-blockers[104,105]. The advantages of nonselective beta blockers are that their cost is low, no expertise is required for their application, and they may prevent other complications, such as bleeding from portal hypertensive gastropathy, ascites, and spontaneous bacterial peritonitis because they can reduce portal pressure[106,107]. The disadvantages of these agents include relatively common contraindications and side effects (fatigue and shortness of breath) that preclude treatment or lead to discontinuation in 15%-20% of patients[106]. Critics of ligation point out that although adverse events are less common with ligation, rare side effects such as ligation-induced ulcer bleeding can be much more severe than most beta-blocker-induced adverse events that are almost never fatal[108]. In most cases, beta-blocker is recommended as a first-line therapy for primary prophylaxis, with EVL being an option in patients who are intolerant to BB or in whom BB is contraindicated.

Carvedilol is a nonselective β-antagonist with α1-receptor antagonist activity, which is a promising alternative that needs to be further explored[26]. Carvedilol may be more effective than propranolol, which resulted in reduced rates of bleeding compared with EVL[109,110]. Carvedilol at low doses (6.25-12.5 mg/d) was compared with endoscopic variceal ligation in a recent randomized controlled trial. Carvedilol was associated with lower rates of first variceal hemorrhage (10% vs 23%) and had an acceptable side-effect profile, unlike endoscopic variceal ligation, for which compliance was low and the rate of first hemorrhage was at the upper end of the range of rates in previous studies[106].

The combination of pharmacological and endoscopic therapy was also investigated, with contrasting results. In the study of Sarin et al[34], endoscopic band ligation plus beta-adrenergic blockers appears to offer no benefit in terms of the prevention of first bleeding when compared with endoscopic band ligation alone.

Theoretically, isosorbidemononitrate (ISMN) might decrease portal pressure but maintain liver perfusion. However, because they are not liver specific, these agents induce arterial hypotension and elicit a reflex splanchnic vasoconstriction with a subsequent reduction in portal blood flow[37]. There are two randomized controlled trials (RCTs) published in full papers investigating the use of nitrates in monotherapy in the prevention of first variceal bleeding[111,112]. Although it was initially thought that ISMN was a safe and effective alternative to propranolol, higher mortality rates were observed in patients who received ISMN.

The choice of treatment should be based on local resources and expertise, patient preference and characteristics, side effects, and contraindications. In most cases, BB is recommended as a first-line therapy for primary prophylaxis, with EVL being an option in patients who are intolerant to BB or in whom BB is contraindicated (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Primary prophylaxis of esophageal variceal bleeding.

NSBB: Non-selective beta-blockers; EVL: Endoscopic variceal ligation.

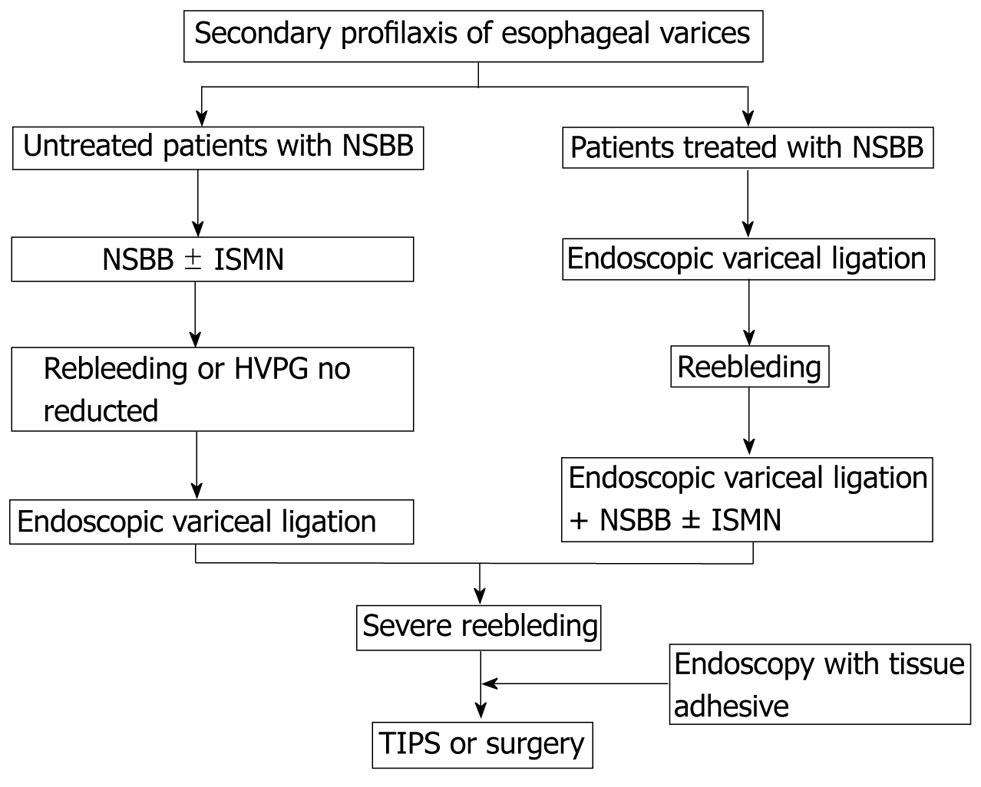

PREVENTION OF VARICEAL REBLEEDING

Once acute bleeding is successfully controlled, rebleeding may occur in approximately two-thirds of patients if further preventive measures are not taken. Several factors have been noted to be associated with the recurrence of variceal bleeding, including portal pressure, poor liver reserve, size of varices, treatment modalities of acute bleeding, infection and portal vein thrombosis[9,28,113]. Secondary prophylaxis should start as soon as possible from day 7 of the index variceal episode.

Over the past two decades, several treatment modalities have been improved and introduced to practice with a decreased rebleeding risk and mortality. Combined pharmacological therapy (nonselective beta-blockers plus nitrates) or the combination of endoscopic variceal ligation plus drug therapy are indicated because of the high risk of recurrence, despite that the side effects are more common than in a single agent therapy (recommended for primary prophylaxis).

Both non-selective beta-blockers and EST have shown efficacy in preventing variceal rebleeding as compared with untreated controls[16,70]. However, other options have improved the results of both pharmacological and endoscopic therapy. EVL has established superiority over EST in numerous studies[49,91]. Combined therapy with beta-blockers and ISMN has been shown to be superior to beta-blockers alone and to EST[114]. The results of trials comparing combined therapy with beta-blockers plus ISMN versus EVL have shown that drug therapy is at least as effective as EVL in preventing variceal rebleeding[115-117].

A meta-analysis showed that rates of rebleeding (from all sources and from varices) are lower with a combination of endoscopic therapy plus drug therapy than with either therapy alone, but without differences in survival[118]. Another recent meta-analysis including 17 RCTs showed that combination of β-blocker and endoscopic treatment significantly reduced rebleeding rates and the mortality as compared with endoscopic treatment alone. Therefore, current guidelines recommend the combined use of endoscopic variceal ligation and nonselective beta-blockers for the prevention of recurrent variceal hemorrhage, even in patients who have had a recurrent hemorrhage despite treatment with nonselective beta-blockers or endoscopic variceal ligation for primary prophylaxis. In patients who are not candidates for endoscopic variceal ligation, the strategy would be to maximize portal pressure reduction by combining nonselective beta-blockers plus nitrates[26,106]. Patients with cirrhosis who are contraindicated or intolerant to beta-blockers are candidates for periodical band ligation[26]. Patients who fail in the endoscopic and pharmacological treatment for the prevention of rebleeding, TIPS with polytetrafluoroethylene is the optional treatment. Covered stents are effective and are the preferred option. Also surgical shunt in Child-Pugh A and B patients is an alternative if TIPS is unavailable. Finally, transplantation provides good long-term outcomes in appropriate candidates and should be considered accordingly. TIPS may be used as a bridge to transplantation[26] (Figure 2).

Figure 2 Secondary prophylaxis of esophageal varices.

NSBB: Non-selective beta-blockers; EVL: Endoscopic variceal ligation; ISMN: Isosorbide mononitrate; TIPS: Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt.