Published online Dec 16, 2012. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v4.i12.575

Revised: March 4, 2012

Accepted: October 10, 2012

Published online: December 16, 2012

Whipple’s disease is a rare chronic systemic infection determined by the Gram-positive bacillus Tropheryma whipplei. The infection usually mainly involves the small bowel, but sometimes other organs are affected as well. Since the current standard clinical and biological tests are nonspecific, diagnosis is very difficult and relies on histopathology. Here we present the case of a 52-year-old man with chronic diarrhea and weight loss whose symptoms had been evolving for 2 years and whose diagnosis came unexpectedly after capsule examination. Diagnosis was confirmed by the histopathologic examination of endoscopic biopsy samples, and treatment with co-trimoxazole resulted in remission of symptoms. We present the first images of Whipple’s disease obtained with the Pillcam Colon 2 video capsule system.

- Citation: Mateescu BR, Bengus A, Marinescu M, Staniceanu F, Micu G, Negreanu L. First Pillcam Colon 2 capsule images of Whipple’s disease: Case report and review of the literature. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2012; 4(12): 575-578

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v4/i12/575.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v4.i12.575

Whipple’s disease is a rare chronic systemic infection determined by the Gram-positive bacillus Tropheryma whipplei. The infection usually mainly involves the small bowel, but sometimes other organs are affected as well. Since the current standard clinical and biological tests are nonspecific, diagnosis is very difficult and relies on histopathology.

A 52-year-old man presented in our department with chronic diarrhea: 6-10 watery stools/d without mucus or blood, low fever (37-38 °C), and progressive asthenia. Stools were exclusively diurnal, described as “sticky”, with no visible blood.

Symptoms started 2 years before, but since then the patient had lost 15 kg, despite his appetite being preserved. He denied drinking alcohol or smoking and didn’t have a significant personal or familial medical history. The patient was repeatedly evaluated in infectious diseases departments, but all the stool cultures (Shigella, Salmonella, enteropathogenic or enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli, and Campylobacter jejuni) were negative. Since the stools were found several times to be positive for Giardia lamblia, the patient underwent several rounds of metronidazole, but to no clinical improvement. Hyperthyroidism and celiac disease were excluded. Multiple gastroscopies found no lesions, except some diffuse white small deposits in D2 (but no anomalies on histopathology). The patient underwent 3 subtotal colonoscopies, which were described as normal.

In addition to antiparasitic drugs, he received antidiarrheals and spasmolytics, with partial, albeit temporary, symptom alleviation. Clinical examination showed the patient to be in a poor state: he was pale, underweight (body mass index 20.1), had a body temperature of 37.5 °C, and suffered diffuse pain and increased bowel sounds at abdominal palpation; discrete peripheral edema, and pulmonary and cardiovascular examinations were normal. No enlarged lymph nodes, skin lesions, or signs of articular involvement were noticed.

The only laboratory anomalies found at this time were a mild hyposideremic anemia (hemoglobin 9.12 g/dL, hematocrit 29%, serum iron 10 µg/dL), with hypoalbuminemia (2.9 g/dL), and an inflammatory syndrome [(C-reactive protein (CRP) 84.7 mg/L], suggesting a lesion of the absorptive epithelium.

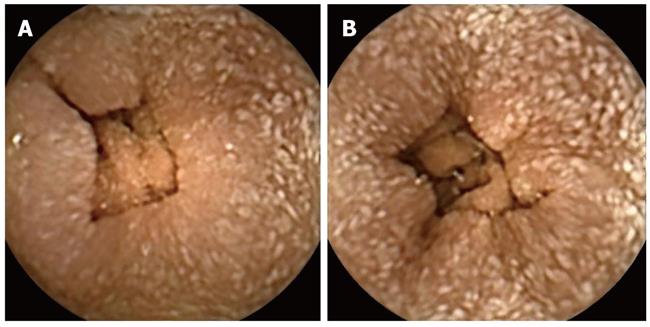

Because the patient refused a new colonoscopy, we used the new Pillcam Colon 2 video capsule from given imaging. There were no anomalies in the esophagus, stomach, or first part of the duodenum, but a “salt and pepper” aspect of the entire small bowel, ending at the ileocecal valve, was noticed. This aspect was due to a myriad of 1-2 mm white deposits (suggesting small intraepithelial abscesses) covering the mucosa (Figure 1). An upper endoscopy and ileocolonoscopy were performed, and multiple biopsies were taken from the small bowel mucosa.

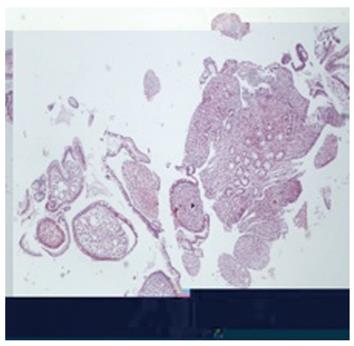

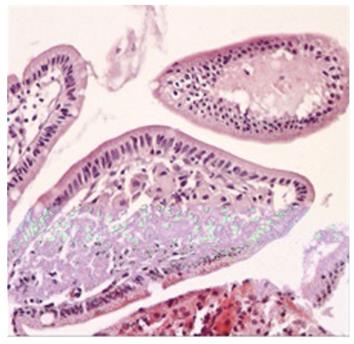

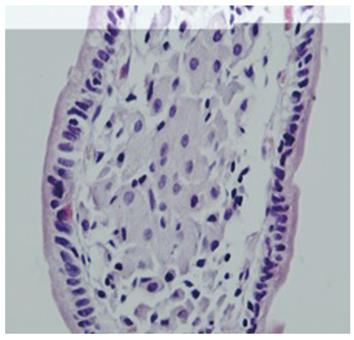

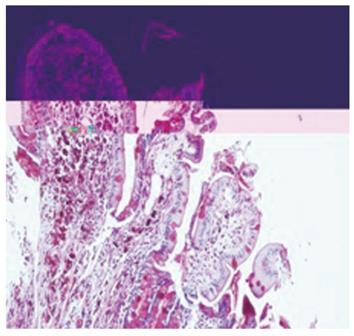

In the pathology lab, after paraffin embedding, the tissue samples were sectioned in 3 µm slices. The slides were then stained with hematoxylin and eosin (HE) and Periodic Acid Schiff (PAS). The HE stain showed: small intestinal mucosa with flattened villi, expanded by a dense infiltrate of foamy macrophages with finely granular eosinophilic cytoplasm, and moderate neutrophilic infiltrate in the lamina propria (Figures 2, 3 and 4). PAS coloration: showed foamy macrophages with frequent PAS-positive bacilli in the cytoplasm, which was suggestive for Tropheryma whipplei (Figure 5).

Given the lack of signs of neurologic involvement, we started oral co-trimoxazole (800/160 mg/d). Ten days later, the patient’s general condition improved, with an increase in appetite, and a slight reduction in bowel movements (4-5/d) and in CRP (51 mg/L). The patient was re-examined every 2 wk. His appetite continued to increase and, by the end of the second month of therapy, he had gained 7 kg in weight. The number of stools decreased to 2-3/d, the CRP fell to 19 mg/dL and his temperature returned to normal; we chose not to administer martial therapy for fear of an iron-induced change in bowel transit, and to allow a spontaneous increase in hemoglobin as a sign of recovering intestinal absorptive functions; indeed there was a 1.1 g/dL increase in hemoglobin at 2 mo. We plan to continue the same treatment and to recheck the endoscopic aspect in 6 mo.

Whipple described for the first time[1] in 1907 this chronic, systemic infection, caused by a Gram-positive bacillus. Although the existence of an infectious organism was postulated by Whipple himself, it took 85 years to completely characterize the bacteria by amplification of the genetic material[2], and another 5 years to isolate it[3]. It was named Tropheryma whipplei (T. whippelii) and included in the same order (Actinomycetales) as the Actinomyces genus. The analysis of its genome and the lack of some essential biosynthetic equipment[4] suggest an intracellular parasite.

Whipple’s disease is very rare; according to a recent review[5], only about 1000 cases have been documented worldwide, mostly in middle-age Caucasian farmers or in those working with soil. The bacillus is present in sewage water and in the soil[6], and the majority of infected humans are healthy carriers who do not develop the disease, pointing toward an underlying genetic predisposition. A particular human leukocyte antigen profile and defects in the cell-mediated immune response predispose to the classical form of the disease, manifesting as diarrhea, malabsorption, weight loss, arthritis or arthralgia, fever, lymphadenopathy, abdominal pain, and neurological signs. The central nervous system (CNS) involvement is the most serious manifestation of the disease, and occurs in up to 43% of cases[7]: headache, cognitive dysfunctions, and disturbances of the ocular movement, in particular progressive supranuclear ophthalmoplegia in conjunction with oculomasticatory myorhythmia, which are considered pathognomonic[8]. Rarely, focal signs may be present or the CNS[9] or joint involvement may be the sole sign of disease. Recently, other clinical entities caused by this bacterium have been recognized; acute self-limited diarrhea or the isolated endocarditis.

The rarity of the disease and the lack of specificity of the clinico-biologic picture make diagnosis very difficult. Confirmation is obtained by finding PAS-positive material (phagocytized bacilli) inside the macrophages from mucosal biopsies by immunohistochemistry, by the identification of T. whipplei in electronic microscopy or through the identification of bacterial DNA with polymerase chain reaction; all tests have a similar sensitivity. We are awaiting novel diagnostic methods; serologic diagnosis is hampered by the reduced reactivity in patients with Whipple’s disease compared with asymptomatic carriers[10].

Colon capsule endoscopy (CCE) represents a noninvasive technology that allows visualization of the colon without requiring sedation and air insufflation. CCE may be a means to overcome the low adherence to colonoscopy in colorectal cancer screening[11].

A second-generation CCE system (PillCam Colon 2; CCE-2) was developed to increase sensitivity for colorectal polyp detection compared with the first-generation system. The PillCam Colon 2 (31 mm × 11 mm) has some new features: the angle of view has been widened from 154° to 172° for each camera, thus offering a panoramic view, and the data recorder was revolutionized (it recognize the location of the capsule and its speed, and permits an adaptive frame rate of 4-35 images/s). The rapid software was upgraded substantially.

In a French study on 128 patients, CCE seemed to be effective in detecting clinically significant colonic findings in patients with an indication of colonoscopy with a high negative predictive value and an excellent tolerance[12].

The results were confirmed in a European multicenter study where CCE-2 appeared to have a high sensitivity for the detection of clinically relevant polypoid lesions. The authors concluded that CCE might be considered an adequate tool for colorectal imaging[13].

In 2010 our team won the ESGE given grant at the United European Gastroenterology Week, with a project on the use of Pillcam Colon 2 for the patients at risk of colorectal cancer (CRC) unwilling or unable to perform colonoscopy[14].

Our patient had three incomplete colonoscopies in other units before, with failures due to technical difficulties and low tolerance of the examination. He refused any new endoscopic examinations, but when we decided to propose the use of Pillcam Colon 2 the patient agreed. The aspect of 1-2 mm white deposits (suggesting small intraepithelial abscesses) covering the mucosa confirmed our suspicion of a small bowel disease, and convinced the patient to perform the more “aggressive” investigations, and thus allowed the biopsies and the histologic confirmation of Whipple’s disease. This is a fine example of the increasing compliance to an examination using CCE. It acceptability is growing globally, not only in CRC screening, but also in many uncommon diseases, as it is patient-friendly. Its use in the pediatric population is well accepted. Previous descriptions of Whipple’s disease using SB were made by different team’s capsules[15,16]. Capsule endoscopy was also used as a monitoring tool to observe mucosal healing after antibiotic therapy[17], but this is the first description, to our knowledge, of Whipple’s disease using the new Pillcam Colon 2 video capsule system.

Before the antibiotic era, Whipple’s disease was always lethal, most frequently due to severe malabsorption. Tetracycline, a preferred drug, like many other antibiotics active against T. whipplei, does not cross the blood-brain barrier, and was associated with a high rate of relapse inside the central nervous system; that is why today it is recommended to use an antibiotic with good penetration into the brain (e.g., co-trimoxazole; in fact only the sulfamethoxazole component is active). A recent randomized trial[18] found the superiority of an induction treatment with intravenous ceftriaxone or meropenem associated with oral co-trimoxazole for 12 mo over the classical 12 mo of oral co-trimoxazole alone. Oral therapy alone has been advocated for those cases without proof of neurologic involvement[19]. However, other trials searching for the best regimen are in progress. Recovery is usually complete, but sometimes the neurologic lesions are irreversible. Relapses should be treated with an alternative regimen, always including antibiotics with good penetration into the brain (e.g., penicillin G, chloramphenicol, and carbapenems). Proof of cure is based on clinical grounds (usually the diarrhea and malabsorption improve in weeks), with polymerase chain reaction (which is quickly negated after efficient therapy), and on repeat endoscopy with biopsies (with the endoscopic changes disappearing in weeks, although the histological aspect may persist for several years[18]).

In conclusion, Whipple’s disease is a rare bacterial infectious disease affecting the gasterointestinal tract which has previously been diagnosed by capsule endoscopy. This may be the first published report with Pillcam Colon 2, which is a new and exciting noninvasive diagnostic technique.

Peer reviewer: Omar Javed Shah, Professor, Head, Department of Surgical Gastroenterology, Sher-i-Kashmir Institute of Medical Sciences, Srinagar 110029, Kashmir, India

S- Editor Song XX L- Editor Roemmele A E- Editor Zhang DN

| 1. | Whipple GH. A hitherto undescribed disease characterized anatomically by deposits of fat and fatty acids in the intestinal and mesenteric lymphatic tissues. Bull Johns Hopkins Hosp. 1907;18:382-391. |

| 2. | Relman DA, Schmidt TM, MacDermott RP, Falkow S. Identification of the uncultured bacillus of Whipple's disease. N Engl J Med. 1992;327:293-301. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 845] [Cited by in RCA: 701] [Article Influence: 21.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Raoult D, Birg ML, La Scola B, Fournier PE, Enea M, Lepidi H, Roux V, Piette JC, Vandenesch F, Vital-Durand D. Cultivation of the bacillus of Whipple's disease. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:620-625. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 357] [Cited by in RCA: 281] [Article Influence: 11.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Raoult D, Ogata H, Audic S, Robert C, Suhre K, Drancourt M, Claverie JM. Tropheryma whipplei Twist: a human pathogenic Actinobacteria with a reduced genome. Genome Res. 2003;13:1800-1809. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Fenollar F, Puéchal X, Raoult D. Whipple's disease. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:55-66. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 426] [Cited by in RCA: 361] [Article Influence: 20.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Fenollar F, Trani M, Davoust B, Salle B, Birg ML, Rolain JM, Raoult D. Prevalence of asymptomatic Tropheryma whipplei carriage among humans and nonhuman primates. J Infect Dis. 2008;197:880-887. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Bai JC, Mazure RM, Vazquez H, Niveloni SI, Smecuol E, Pedreira S, Mauriño E. Whipple's disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;2:849-860. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Durand DV, Lecomte C, Cathébras P, Rousset H, Godeau P. Whipple disease. Clinical review of 52 cases. The SNFMI Research Group on Whipple Disease. Société Nationale Française de Médecine Interne. Medicine (. Baltimore). 1997;76:170-184. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Panegyres PK. Diagnosis and management of Whipple's disease of the brain. Pract Neurol. 2008;8:311-317. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Fenollar F, Amphoux B, Raoult D. A paradoxical Tropheryma whipplei western blot differentiates patients with whipple disease from asymptomatic carriers. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49:717-723. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Sieg A. Capsule endoscopy compared with conventional colonoscopy for detection of colorectal neoplasms. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;3:81-85. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 12. | Gay G, Delvaux M, Frederic M, Fassler I. Could the colonic capsule PillCam Colon be clinically useful for selecting patients who deserve a complete colonoscopy?: results of clinical comparison with colonoscopy in the perspective of colorectal cancer screening. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:1076-1086. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Spada C, Hassan C, Munoz-Navas M, Neuhaus H, Deviere J, Fockens P, Coron E, Gay G, Toth E, Riccioni ME. Second-generation colon capsule endoscopy compared with colonoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;74:581-589.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 202] [Cited by in RCA: 170] [Article Influence: 12.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Keane MG, Shariff M, Stocks J, Trembling P, Cohen PP, Smith G. Imaging of the small bowel by capsule endoscopy in Whipple's disease. Endoscopy. 2009;41 Suppl 2:E139. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Gay G, Delvaux M, Frederic M. Capsule endoscopy in non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs-enteropathy and miscellaneous, rare intestinal diseases. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:5237-5244. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Dzirlo L, Blaha B, Müller C, Hubner M, Kneussl M, Huber K, Gschwantler M. Capsule endoscopic appearance of the small-intestinal mucosa in Whipple's disease and the changes that occur during antibiotic therapy. Endoscopy. 2007;39 Suppl 1:E207-E208. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Feurle GE, Junga NS, Marth T. Efficacy of ceftriaxone or meropenem as initial therapies in Whipple's disease. Gastroenterology. 2010;138:478-86; quiz 11-2. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 120] [Cited by in RCA: 112] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Schneider T, Moos V, Loddenkemper C, Marth T, Fenollar F, Raoult D. Whipple's disease: new aspects of pathogenesis and treatment. Lancet Infect Dis. 2008;8:179-190. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 257] [Cited by in RCA: 223] [Article Influence: 13.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |