Published online Oct 16, 2012. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v4.i10.448

Revised: August 26, 2012

Accepted: October 10, 2012

Published online: October 16, 2012

Capsule endoscopy was conceived by Gabriel Iddan and Paul Swain independently two decades ago. These applications include but are not limited to Crohn’s disease of the small bowel, occult gastrointestinal bleeding, non steroidal anti inflammatory drug induced small bowel disease, carcinoid tumors of the small bowel, gastro intestinal stromal tumors of the small bowel and other disease affecting the small bowel. Capsule endoscopy has been compared to traditional small bowel series, computerized tomography studies and push enteroscopy. The diagnostic yield of capsule endoscopy has consistently been superior in the diagnosis of small bowel disease compared to the competing methods (small bowel series, computerized tomography, push enteroscopy) of diagnosis. For this reason capsule endoscopy has enjoyed a meteoric success. Image quality has been improved with increased number of pixels, automatic light exposure adaptation and wider angle of view. Further applications of capsule endoscopy of other areas of the digestive tract are being explored. The increased transmission rate of images per second has made capsule endoscopy of the esophagus a realistic possibility. Technological advances that include a double imager capsule with a nearly panoramic view of the colon and a variable frame rate adjusted to the movement of the capsule in the colon have made capsule endoscopy of the colon feasible. The diagnostic rate for the identification of patients with polyps equal to or larger than 6 mm is high. Future advances in technology and biotechnology will lead to further progress. Capsule endoscopy is following the successful modern trend in medicine that replaces invasive tests with less invasive methodology.

- Citation: Adler SN, Bjarnason I. What we have learned and what to expect from capsule endoscopy. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2012; 4(10): 448-452

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v4/i10/448.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v4.i10.448

Two researchers, Gabriel Iddan and Paul Swain, independently and extensively investigated the possibility of transmitting images from the digestive tract to an extracorporeal receiver by swallowing a wireless capsule camera. Technological advancements lead to miniaturization of the electronic image processing unit (charged couple device, 1969) and the development of a more energy efficient processor and transmitter of digital information (CMOS 1994). The imagination of these two researchers began to reach the fringes of reality. In 1996, Paul Swain-a gastroenterologist-demonstrated that a wireless ingested capsule could transmit on line images from a pig stomach to an outside receiver. At this point this finding remained in the realm of a curiosity. Gabriel Iddan-an electro optic engineer, PhD-contacted Paul Swain and offered him to join forces to conquer new territory in the field of gastroenterology. The next great successful step forward in the research of these scientists was to cooperate and not to compete with each other. And so it came that in 1999 the internal review board permitted the ingestion of a prototype capsule endoscope in a human. Paul Swain executed this honor in Israel. Iddan and Swain had obtained proof of principle.

The concept of wireless capsule endoscopy became more intriguing. Yet the pivotal question remained. Did this device carry any medical relevance? A clinical trial was designed to address this question. A gastrointestinal medical condition, occult gastrointestinal bleeding, was chosen which was known to challenge treating physicians. These are patients with bleeding from the digestive tract who have undergone a work up which includes an esophagogastroduodenoscopy, colonoscopy and some kind of small bowel imaging such as a small bowel series or computerised tomography enterography with negative results. The plan was to take 20 such patients and have the capsule compete with the best available technology at that time, namely fiberoptic enteroscopy. Capsule endoscopy outdid fiberoptic enteroscopy by a ratio of 2:1. Lewis and Swain presented their results at DDW in 2001. The United States Food and Drug Administration immediately recognized the benefit of this concept in summer of 2001. Lewis and Swain’s findings were since confirmed by more than a dozen studies. In the meanwhile capsule endoscopy of the small bowel has proven its clinical relevance in diagnosing non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) induced small bowel disease, Crohn’s disease, neoplastic disease and others.

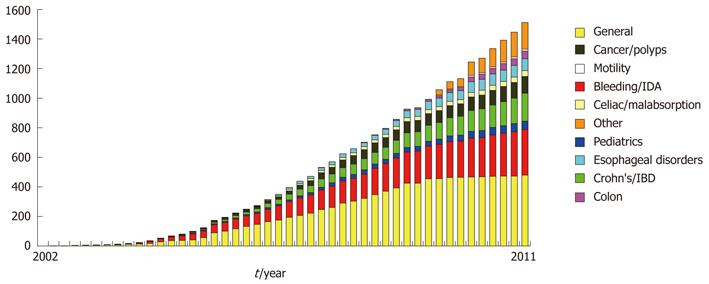

In January 2002, I gave a lecture on capsule endoscopy and pointed out that 3000 capsule ingestions had already taken place. The importance of capsule endoscopy to the field of gastroenterology is reflected in the fact that in the following 10 years over one and half million capsule examinations have been performed. The plethora of information and publications that has accumulated from capsule endoscopy can be seen in Figure 1. That same year I experienced a very moving experience when I presented a review on small bowel pathology induced by NSAIDs. The previous speaker at the conference was Professor Bjarnason. When I asked him if he was the Professor Bjarnason who based on intestinal permeability studies nearly two decades earlier had predicted that NSAIDs caused small bowel mucosal damage he modestly responded with yes. Then I continued to inform him that it was for me a true honor to present to him the images of capsule endoscopy that proved he had been right all along.

Capsule endoscopy has undergone many further developments. Picture quality has been improved by the introduction of devices with wider angle of view, better lenses and automatic control of light exposure to improve performance of small bowel survey by the capsule. Capsule endoscopy of the small bowel has made traditional small bowel series obsolete. What has been proven to be correct for the upper gastrointestinal tract and the colon has been proven to be true for the small bowel, too. Direct optical inspection is superior to barium studies, for this reason the gastroscope replaced the upper gastrointestinal series, the colonoscope the barium enema and now capsule endoscopy has replaced the small bowel series examination. Triantafyllou has made the interesting observation that use of a capsule camera with two imagers, an imager at each end of the capsule, for the evaluation of small bowel pathology will increase the diagnostic yield by 5 percent[1]. His observation is in good keeping with our own. Severity of Crohn’s disease is influenced by the fact whether the standard capsule, one imager at one end and the antenna at the other end of the capsule, enters the small bowel with the camera leading or the antenna leading[2].

A further step forward is the image modifier software added to the reading package of Given Imaging. I find it very helpful to modify basic colors. For instance partially oxidized blood appears black with standard review software. The FICE option of the new software turns this dark blood into bright red. Pathological mucosa appears different from the background healthy mucosa in blue mode. Whenever I encounter a finding that may be a small superficial ulceration versus overlying debris, I activate the blue mode. If it is a true ulceration or mucosal break then the margin of the ulcer next to healthy mucosa is reflected as a thin hemorrhagic border. The development of this technology may open the doors to optical biopsy.

The advent of double balloon (push pull endoscopy) did not replace the need for capsule endoscopy of the small bowel. Controlled studies have demonstrated that these two procedures are complementary. The diagnostic yield of capsule endoscopy and the ability to screen the entire small bowel are superior with capsule endoscopy. Furthermore capsule endoscopy can indicate if double balloon endoscopy should be performed via the oral or anal route[3]. These studies conclude that in case of suspected small bowel disease a capsule study is to be performed. The results of the capsule study may indicate the need for therapeutic or diagnostic intervention. That is when double balloon endoscopy should be performed.

Capsule endoscopy has been extended to examine the esophagus. Capsule transit time via the esophagus is significantly faster than transit time in the small bowel. For this reason two cameras transmitting images at a high rate (14 frames per second) have been placed at each end of the esophageal capsule camera. These cameras with high transmission screen the esophagus well. The esophageal capsule has a very high diagnostic sensitivity for diseases such as reflux esophagitis, Barrett’s esophagus or esophageal varices[4]. The advantages for using capsule endoscopy are the lack of need for sedation, non invasiveness and the possibility of performing the procedure at the first office visit. The disadvantage is that the esophageal capsule is competing with a very good, albeit invasive device, the gastroscope, which is in most places cheaper.

The fact that a noninvasive method could provide direct visual inspection of the intestinal lining made the concept of capsule inspection of the colon very attractive. The procedure to obtain direct inspection by standard colonoscopy requires the use of an invasive test with sedation. Although the risks for severe complications with standard colonoscopy are small there is an underrated amount of significant post procedural complaints leading to increased emergency room visits after colonoscopy[5]. Compliance of healthy individuals to undergo colonoscopy for primary colon cancer prevention is suboptimal.

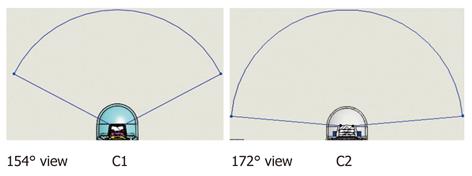

Yet the obstacles to produce a capsule camera that could screen the colon were challenging for the following reasons: (1) The small bowel is narrow compared to the large bowel. As the capsule camera enters the small bowel the lumen of the small bowel is by and large too small to permit the capsule to turn along its own axis. Therefore the capsule will enter either with the camera leading or the part of the capsule containing the antenna leading. The capsule will remain oriented in the given position as it entered the small bowel along its journey through the small bowel. For this reason the single camera of the small bowel capsule will screen the entire small bowel mucosa. This is not true for the colon. There the capsule can tumble backwards and forwards in the wide lumen of the colon. If this were to happen then there would be areas of the colon that the capsule would capture twice and areas that the capsule would not capture at all. The engineers at Given Imaging designed a colon capsule that has two cameras, one camera at each end (Figure 2). The colonic mucosa is visualized from both directions simultaneously and thus complete visual coverage of the entire colon is guaranteed; (2) The transit time to reach the end of the colon is much longer than the time required for the capsule to reach the cecum. Furthermore the colon capsule consumes more energy than the small bowel capsule since it transmits images from two cameras. While the energy needs of the colon capsule are that much greater than the small bowel capsule, the amount of energy available to the capsule for transmitting images to the external recorder is limited to two watch batteries. To guarantee adequate energy supplies for the transmission of images from the colon, the colon capsule was put to sleep for an hour and a half five minutes after ingestion; and (3) Whereas in standard colonoscopy some minimal amount of liquid debris can be aspirated via the colonoscope, minimal amount of debris may compromise the capsule’s ability to identify pathological changes. A more vigorous bowel preparation had to be offered to patients to assure proper cleansing for colon capsule examinations. A clear liquid diet prior to the day of examination and split dose Polyethyleneglycol ingestion achieved adequate cleansing in 80% of patients[6].

The first colon capsule was put to the test in the year 2005 and 2006. The results of three studies were encouraging. Firstly the bowels could be adequately cleansed in 80% of patients. Secondly the capsule could traverse through the entire gastrointestinal tract and transmit images from the entire colon. Finally the capsule did indentify pathologies such as polyps, tumors, colitis, diverticulosis and internal hemorrhoids. The suboptimal identification of patients with colonic polyps as compared to standard colonoscopy fell short of expectations.

What I find impressive is that the engineers at Given Imaging did not accept defeat. Instead of surrendering they analyzed in detail the shortcomings of the colon capsule. With the results of their analysis they created the second generation colon capsule. Here are some of the changes that they made. The angle of view of the first generation colon capsule camera is 154 degrees. The angle of view has been widened to 172 degrees for each camera of the second generation colon capsule. This change provides a near full panorama view (Figure 3). The Data Recorder 3 is a true revolution in capsule endoscopy. This device has been endowed with artificial intelligence. It communicates with the capsule and the capsule is programmed to carry out the instructions received by the data recorder. Not only does this new data recorder speak to the capsule camera, it also communicates with the patient undergoing the colon capsule examination. Let me walk you, the reader, through the process.

The colon capsule is ingested by the patient. After three minutes the rate of transmission is reduced to 16 images per minute to conserve energy. The received images are constantly analyzed and recognized by data recorder 3. If after one hour data recorder 3 notices that the colon capsule is still in the stomach it will talk to the subject by activating an alarm ring tone, a vibrating device attached to the antenna and display number 0 on the liquid crystal display screen. The patient will consult his instruction sheet and learn that the number 0 indicates that he/she has to ingest a prokinetic agent such domperidone or metoclopramide. However if the capsule has left the stomach and entered the small bowel, the artificial intelligence of data recorder 3 will recognize that the capsule is now in the small bowel. Data recorder 3 will order the capsule to raise the transmission rate from 16 images per minute to 4 images per second. At the same time data recorder 3 will communicate with the patient and tell him to ingest his booster. The purpose of this booster is to shorten small bowel transit time and to maintain adequate cleanliness of the bowel. The artificial intelligence of the data recorder will recognize if the capsule is stationary or in motion. Once data recorder 3 recognizes that the capsule is in motion it orders the capsule to raise its transmission rate to 35 images per second. The process of recognition to execution literally takes place in a split second. This rapid transmission rate (35 images per second) provides adequate number of colonic images while the capsule is in motion especially while flying through the transverse colon.

The software program for colon capsule 2 has been equipped with a polyp size assessor. The cursor is drawn from one side of the polyp to the other and the algorithm spits out the size of the polyp in mm. The system is reliable. The same polyp seen from distance or from close up will have the same size.

While these technological achievements are very impressive (a data recorder talking to capsule and patient, analyzing images, determining location, position-stationary versus motion, altering transmission rate) the same question has to be asked as we had asked ourselves at the outset of capsule endoscopy in the year 2000. Is this a high tech toy or a medically relevant tool?

We engaged in a five center prospective double blind feasibility study in Israel in which this second generation colon capsule was compared to standard colonoscopy for the identification of patient with colonic polyps. 104 patients were enrolled. Whereas in the European multicenter trial published in 2009 the sensitivity to identify patients with polyps was only 60% the sensitivity in the multicenter Israel trial with the second generation colon capsule rose to 90%[7]. This marked improved diagnostic sensitivity was reproduced by a recent European study with the second generation colon capsule[8]. This improvement (raise in diagnostic sensitivity from 60% to 90%) has to be attributed to the revolutionary new capsule platform of this second generation colon capsule. The three previous studies with the first generation colon capsule had a very similar design as our present study. Good bowel cleansing was obtained at similar rates as in this new study. The only factor which set this second generation colon capsule study apart from the previous studies is the new technological platform. Protocol restraints contributed to a relatively low specificity. Colonoscopy was defined as the gold standard. Even in good hands standard colonoscopy is known to miss colonic polyps[9,10]. If the capsule identified a polyp and the first colonoscopy missed the polyp yet the polyp was found on repeat colonoscopy this was counted as a false positive capsule finding. The same is true for polyp miss match between colon capsule and colonoscopy. If colon capsule identified the polyp to be 12 mm large and the colonoscopy defined the polyp to be 9 mm then this too was counted as a false positive capsule result.

The negative predictive value of 97% is very high and is clinically very meaningful. The physician offering his patient a colon capsule study can tell his patient that a negative study has 97% accuracy that he harbors no polyps.

The fact that the intelligent data recorder 3 not only talks to the capsule but to the patient too has opened the door to offer colon capsule studies as an outpatient procedure. Increasing compliance to participate in colon screening programs is essential to reduce colon cancer mortality in our society. Hassan et al[11] have calculated relying on figures from first generation colon capsule studies with a relative low sensitivity to detect patients with colonic polyps that increasing compliance to participate in capsule colon cancer screening by 4% would save the same amount of lives as colonoscopy does today. With the second generation colon capsule only a 2% increase in compliance will lead to an equal number of patients saved by colon cancer.

The future will be brighter and better than the past and present. Our good technologies will be replaced and retired by better technologies. My immediate expectations are that we will enjoy capsule endoscopes that will give us a realistic assessment of the entire gastrointestinal tract. Invasive diagnostic tests will be a thing of the past. Invasive tests will be reserved for therapeutic interventions. My further expectations are that we will not only look and the mucosal surface of the gastrointestinal tract but that we will focus on the host of molecular signals present in the lumen of the digestive tract. Molecular markers will include tumor markers, oncogenes or oncogene derived proteins, tissue transglutaminase, inflammatory parameters such as calprotectin and others. For us to get there we need the dreams of a Gabriel Iddan and a Paul Swain with the commitment and tenacity that these young and bright people at the Research and Development department of Given Imaging have. It is first and foremost to these bright and dedicated young engineers and scientists that I owe the thrill of the past ten years that permitted me to be part of the team that moved the border of knowledge another mile forward.

So my message to all of you, let’s keep our dreams alive.

Peer reviewers: Federico Carpi, PhD, Assistant Professor, Interdepartment Research Centre “E. Piaggio”, School of Engineering, University of Pisa, Via Diotisalvi 2, Pisa 56100, Italy; Shinji Tanaka, MD, PhD, Professor, Department of Endoscopy, Hiroshima University Hospital, 1-2-3 Kasumi, Minami-ku, Hiroshima 734-8551, Japan

S- Editor Song XX L- Editor A E- Editor Zhang DN

| 1. | Triantafyllou K, Papanikolaou IS, Papaxoinis K, Ladas SD. Two cameras detect more lesions in the small-bowel than one. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:1462-1467. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Adler SN, Metzger YC. Heads or tails, does it make a difference? Capsule endoscope direction in small bowel studies is important. Endoscopy. 2007;39:910-912. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Gay G, Delvaux M, Fassler I. Outcome of capsule endoscopy in determining indication and route for push-and-pull enteroscopy. Endoscopy. 2006;38:49-58. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 168] [Cited by in RCA: 143] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Koslowsky B, Jacob H, Eliakim R, Adler SN. PillCam ESO in esophageal studies: improved diagnostic yield of 14 frames per second (fps) compared with 4 fps. Endoscopy. 2006;38:27-30. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Leffler DA, Kheraj R, Garud S, Neeman N, Nathanson LA, Kelly CP, Sawhney M, Landon B, Doyle R, Rosenberg S. The incidence and cost of unexpected hospital use after scheduled outpatient endoscopy. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170:1752-1757. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Eliakim R, Fireman Z, Gralnek IM, Yassin K, Waterman M, Kopelman Y, Lachter J, Koslowsky B, Adler SN. Evaluation of the PillCam Colon capsule in the detection of colonic pathology: results of the first multicenter, prospective, comparative study. Endoscopy. 2006;38:963-970. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 239] [Cited by in RCA: 222] [Article Influence: 11.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Eliakim R, Yassin K, Niv Y, Metzger Y, Lachter J, Gal E, Sapoznikov B, Konikoff F, Leichtmann G, Fireman Z. Prospective multicenter performance evaluation of the second-generation colon capsule compared with colonoscopy. Endoscopy. 2009;41:1026-1031. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 204] [Cited by in RCA: 209] [Article Influence: 13.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Spada C, Hassan C, Munoz-Navas M, Neuhaus H, Deviere J, Fockens P, Coron E, Gay G, Toth E, Riccioni ME. Second-generation colon capsule endoscopy compared with colonoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;74:581-589.e1. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Rex DK, Cutler CS, Lemmel GT, Rahmani EY, Clark DW, Helper DJ, Lehman GA, Mark DG. Colonoscopic miss rates of adenomas determined by back-to-back colonoscopies. Gastroenterology. 1997;112:24-28. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1089] [Cited by in RCA: 1048] [Article Influence: 37.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Heresbach D, Barrioz T, Lapalus MG, Coumaros D, Bauret P, Potier P, Sautereau D, Boustière C, Grimaud JC, Barthélémy C. Miss rate for colorectal neoplastic polyps: a prospective multicenter study of back-to-back video colonoscopies. Endoscopy. 2008;40:284-290. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 351] [Cited by in RCA: 370] [Article Influence: 21.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Hassan C, Zullo A, Winn S, Morini S. Cost-effectiveness of capsule endoscopy in screening for colorectal cancer. Endoscopy. 2008;40:414-421. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |