Published online Jun 16, 2011. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v3.i6.129

Revised: May 10, 2011

Accepted: May 17, 2011

Published online: June 16, 2011

Bezoars are masses or concretions of indigestible materials found in the gastrointestinal tract, usually in the stomach. Case reports of childhood gastric bezoars (particularly phytobezoars) are rare. In this age group they represent a therapeutic challenge, because of the combination of hard consistency and great size. The present report concerns an 8-year-old boy with a history of high fruit intake, presenting with abdominal complaints due to a large gastric phytobezoar. Successful endoscopic fragmentation coupled with suction removal was accomplished, using a standard-channel endoscope. Although laborious, it has been shown to be an efficacious and safe procedure, completed in one session. Endoscopic techniques for pediatric bezoar management may thus be cost effective, taking into account the avoidance of surgery, the length of the hospital stay and the number of endoscopic sessions.

- Citation: Azevedo S, Lopes J, Marques A, Mourato P, Freitas L, Lopes AI. Successful endoscopic resolution of a large gastric bezoar in a child. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2011; 3(6): 129-132

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v3/i6/129.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v3.i6.129

Bezoars are masses or concretions of indigestible materials found in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, usually in the stomach. Although their true incidence in the paediatric population is unknown, bezoars are most commonly seen in females, adolescents and in children with neurological or psychiatric disorders[1-3].

Bezoars are usually classified according to their composition into trichobezoars, phytobezoars, lactobezoars and medication bezoars. The first type is the most commonly found in children. Their clinical presentation is related with their location and generally includes abdominal discomfort and pain, nausea, vomiting, early satiety, loss of appetite and weight loss. Complications arising from the presence of bezoars, although rare, can be severe and associated with high morbidity and potential mortality[4-6]. In addition to the clinical history, imaging of the gastrointestinal tract may facilitate diagnosis, prior to performing an endoscopy[2,3,7]. Treatment options for bezoars depend on their composition, location and size. Currently, dissolution therapy and endoscopic fragmentation and/or aspiration have been considered as the initial management tools and are associated with a wide range of efficacy[8-12]. However, large gastric phytobezoars may be difficult to remove endoscopically because of their inaccessibility and surgery may be required in cases were more conservative measures have failed[8,13].

To date, there are very few case reports concerning childhood gastric bezoars (particularly phytobezoars) and their resolution through therapeutic intervention[2,4,5,9]. The present report, provided further information on phytobezoar presentation and endoscopic management at pediatric age. It concerns the occurrence of a large gastric phytobezoar (possibly a dyospirobezoar) in an 8-year-old boy without specific risk factors other than heavy fruit ingestion. Successful endoscopic resolution is reported and a brief literature review is included, with special emphasis on therapeutic options.

An 8-year-old male of southwest European origin was admitted to the Emergency Paediatric Department of the local hospital complaining of persistent vomiting and severe epigastric pain. His symptoms had begun two years before and included morning halitosis, daily episodes of mid epigastric pain after meals, occasional vomiting, nausea, early satiety and no weight gain. These symptoms had progressed steadily over several months and had become more severe six weeks prior to admission. At the time of presentation the child had been experiencing vomiting and severe abdominal pain after all meals, for the previous four days.

A review of the family history revealed no significant disease and the patient’s personal history was unremarkable. However, assessment of nutrition habits showed a high daily ingestion of a diversity of fruits (about 2-10 pieces of fruit/day, including persimmons) since he was 2 years old. In fact, the parents were owners of a fruit shop and thus the child had free access to fruit.

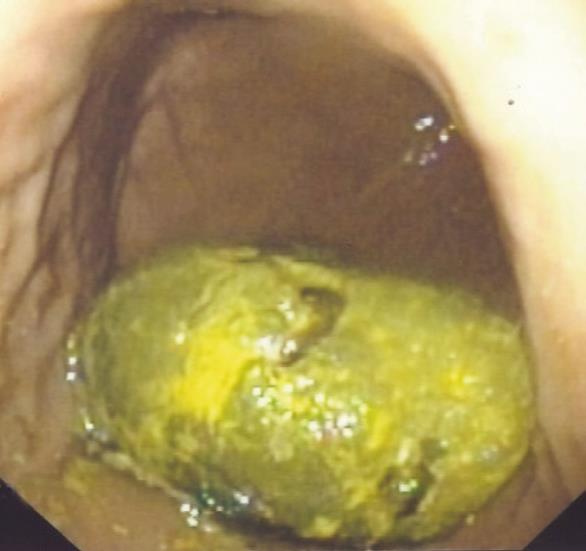

On admission to the local hospital, physical examination revealed signs of slight dehydration, diffuse abdominal tenderness and a weight of 23 Kg. Laboratory tests showed no abnormalities and plain abdominal X-ray as well as abdominal ultrasound (performed on admission) were described as normal. The child remained at the local hospital for supportive measures but no bezoar was suspected. However, as no improvement occurred, six days after admission she was referred to a tertiary centre (Paediatric Gastroenterology Unit), for endoscopic evaluation. Under general anaesthesia the patient was subjected to upper digestive endoscopy (standard endocopy equipment - Olympus GIF -160), which revealed the presence of a large bezoar (9 cm × 5 cm) located in gastric corpus, yellow-greenish in color and of a very hard consistency (Figure 1). The gastric mucosa was normal, as were the oesophageal and duodenal mucosa. An initial attempt at endoscopic fragmentation using several accessories (electrosurgical snare, Dormia basket, mouse-teeth clamp) was unsuccessful, due to the very hard consistency of the bezoar. A further attempt, with the collaboration of the Adult Gastroenterology Department, using repeated argon-plasma fulguration, allowed fragmentation of the bezoar and thereafter complete retrieval and/or suction of residual fragments. This demanding procedure took three hours and inevitably involved some collateral disruption. The macroscopic appearance of a piece of the bezoar obtained during endoscopy suggested that it was a phytobezoar, and this was confirmed by histological examination. The patient was discharged 8 h post-endoscopy, clinically well, and with complete symptom remission. During the 10-mo follow-up period, he did not complain of any discomfort, remaining asymptomatic and recovering weight (weight gain 8 kg).

Gastric bezoars are a rare phenomenon resulting from the accumulation of ingested material, found in less than 1% of patients undergoing upper gastrointestinal endoscopy[1-4]. Bezoars are currently defined based on their composition: (1) phytobezoars are mainly composed by vegetable material (usually vegetables and fruits), such as cellulose, tannin and lignin (which polymerise in the stomach); a disopyrobezoar is a particular type of phytobezoar resulting from the consumption of the persimmon fruit[1,4,5,10]; (2) trichobezoars composed of ingested hair; and (3) pharmacobezoars which occur when long-acting medicinal preparations coalesce in the gastrointestinal tract.

Although bezoars grow as ingestion of indigestible materials continues, their pathogenesis is complex. The major risk factors for phytobezoar formation are altered gastric structure, compromised gastric function (for example previous gastric surgery), dental problems, poor mastication and the ingestion of indigestible material. These factors are usually absent in healthy children and thus phytobezoars are rare in this group[2,4,5,9]. Interestingly, and different from most of the reported pediatric bezoar cases, our patient had no psychiatric disturbance and his only risk factor was a history of high consumption of various kinds of fruits, including persimmons, which resulted in the formation of a massive bezoar. In fact, ingestion of persimmons is considered the most common cause of phytobezoars in some countries[2,3,4].

Diagnosis of GI phytobezoars may be difficult and usually depends on evidence from imaging studies and from endoscopy. Morbidity related to gastrointestinal bezoars is not insignificant, both in children and adults, and a broad spectrum of associated complications has been reported. These include protein-losing enteropathy, steatorrhea, vitamin deficiencies, pancreatitis, invagination, gastric ulcer or gastritis, gastrointestinal bleeding and intestinal obstruction or perforation[1-6,8]. Hospital evaluation of trichobezoar cases is often delayed as they form insidiously. Typical symptoms in such patients are epigastric discomfort and pain, nausea, vomiting, early satiety, hematemesis and change in intestinal habits. However, clinical manifestations vary, depnding on the location of bezoar, from no symptoms to acute abdominal syndrome, e.g. epigastric distention, abdominal pain and acid regurgitation. Our patient, despite suffering for a long period from weight loss, loss of appetite, nausea, vomiting and epigastric pain, remained uninvestigated and undiagnosed.

Management modalities for gastric bezoars include endoscopic therapy with fragmentation, medical treatment by chemical/enzymatic dissolution and surgery[8-13] (conventional surgery as well as video-laparoscopic surgery). Surgery is obviously reserved for recalcitrant cases when more conservative measures have failed. Several endoscopic methods and instruments for breaking up gastric bezoars have been reported, with variable efficacy, including the use of polypectomy snares, biopsy forceps, lithotripsy and endoscopic suction removal with large-channel endoscopy. These techniques may be associated with some procedure complications such as bleeding, overtube-related complications such as esophago-gastric iatrogenic injuries (including perforation, laceration, hematoma and ulceration) and intestinal obstruction (caused by the fragmented bezoar). Furthermore, these procedures are recognized as time consuming and demand highly trained professionals with experience in several endoscopic techniques[4].

Currently, various dissolving agents have also been used, including cellulase, acetylcystein, papain and Coca Cola®[8-11]. The degree of reported efficacy is variable and to date there are only small series of patients reporting the use of cola and N- acetylcyteine for bezoar dissolution (this last agent is most effective in dissolution of lactobezoars).

For gastric phytobezoares, there are few pediatric case reports and no standardized therapeutic approaches defined. There are also few available reports concerning adult phytobezoars and therefore limited experience in conservative methods for evacuation[8,12,14,16]. Conservative resolution of both pediatric and adult phytobezoars is, in fact, challenging. Because of their hard consistency (particularly disospyrobezoars), endoscopic therapy with fragmentation or dissolution sometimes cannot be accomplished and surgery is necessary, with increased associated morbidity. Although there are a few interesting reports, including some in children, where the dissolution of diospyrobezoars was achieved out effectively and safely with cola, including some with the direct injection of small amounts of cola directly into the phytobezoars[10,11], complete dissolution may not be achieved by cola use alone. In addition, chemical dissolution usually requires a long period of time and complications may develop, such as electrolyte imbalance, gastric ulcers and bleeding[2,8,10].

Our patient’s bezoar was fragmented endoscopically after several attempts, in only one endoscopy session. Although this was a demanding session, its duration might be regarded as acceptable, as there were no procedure-related complications. Considering the predictable low rate of medical dissolution, the young age of the patient and the hard bezoar consistency, no chemical/enzymatic dissolution was attempted, as it might have required a yet longer procedure time. In addition, dissolution is not risk free as it requires a variable period of nasogastric intubation, and ingestion of a considerable volume of liquid which can lead to electrolyte imbalance, gastric ulcers and bleeding. It is possible however that combination management of gastric phytobezoars with cola (or other dissolving agent) and endoscopic fragmentation might be cost-effective and decrease the number of endoscopic sessions and accessories that are used, as well as the hospital stay[15,16].

In conclusion, although gastric phytobezoars very rarely occurin children, they may represent a therapeutic challenge due to the combination of hard consistency and great size. As shown in the present report, endoscopic fragmentation coupled with subsequent suction removal, using a standard-channel endoscope and conventional accessories, although laborious, can be an efficacious and safe procedure, completed in only one session, within acceptable time.

Endoscopic techniques for bezoar management in children may thus be cost effective, given the avoidance of surgery, the length of the hospital stay, the number of endoscopic sessions and the accessories used. Furthermore, the present report underscores the importance of collaboration with adult gastroenterologists, as they have great experience in a wide range of therapeutic endoscopy techniques, such as argon-plasma fulguration, which are less commonly used in the paediatric population. Finally, consideration of non-psychiatric causes for this disorder in otherwise healthy children, must be emphasized.

Peer reviewer: Noriya Uedo, Director, Endoscopic Training and Learning Center; Vice Director, Department of Gastrointestinal Oncology, Osaka Medical Center for Cancer and Cardiovascular Diseases, Osaka 537-8511, Japan

S-Editor Wang JL L-Editor Hughes D E-Editor Zhang L

| 2. | Lee J. Bezoars and foreign bodies of the stomach. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 1996;6:605-619. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Zhang RL, Yang ZL, Fan BG. Huge gastric disopyrobezoar: a case report and review of literatures. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:152-154. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Choi SO, Kang JS. Gastrointestinal phytobezoars in childhood. J Pediatr Surg. 1988;23:338-341. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Koç O, Yildiz FD, Narci A, Sen TA. An unusual cause of gastric perforation in childhood: trichobezoar (Rapunzel syndrome). A case report. Eur J Pediatr. 2009;168:495-497. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Ventura DE, Herbella FA, Schettini ST, Delmonte C. Rapunzel syndrome with a fatal outcome in a neglected child. J Pediatr Surg. 2005;40:1665-1667. [PubMed] |

| 7. | El Hajjam M, Lakhloufi A, Bouzidi A, Kadiri R. CT features of a voluminous gastric trichobezoar. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 2001;11:131-132. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Koulas SG, Zikos N, Charalampous C, Christodoulou K, Sakkas L, Katsamakis N. Management of gastrointestinal bezoars: an analysis of 23 cases. Int Surg. 2008;93:95-98. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Heinz-Erian P, Klein-Franke A, Gassner I, Kropshofer G, Salvador C, Meister B, Müller T, Scholl-Buergi S. Disintegration of large gastric lactobezoars by N-acetylcysteine. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2010;50:108-110. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Lee BJ, Park JJ, Chun HJ, Kim JH, Yeon JE, Jeen YT, Kim JS, Byun KS, Lee SW, Choi JH. How good is cola for dissolution of gastric phytobezoars? World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:2265-2269. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Okamoto Y, Yamauchi M, Sugihara K, Kato H, Nagao M. Is coca-cola effective for dissolving phytobezoars? Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;19:611-612. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Blam ME, Lichtenstein GR. A new endoscopic technique for the removal of gastric phytobezoars. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;52:404-408. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Nirasawa Y, Mori T, Ito Y, Tanaka H, Seki N, Atomi Y. Laparoscopic removal of a large gastric trichobezoar. J Pediatr Surg. 1998;33:663-665. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Chou JW, Lai HC. Obstructing small bowel phytobezoar successfully treated with an endoscopic fragmentation using double-balloon enteroscopy. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7:e51-e52. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Gayà J, Barranco L, Llompart A, Reyes J, Obrador A. Persimmon bezoars: a successful combined therapy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;55:581-583. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Lin CS, Tung CF, Peng YC, Chow WK, Chang CS, Hu WH. Successful treatment with a combination of endoscopic injection and irrigation with coca cola for gastric bezoar-induced gastric outlet obstruction. J Chin Med Assoc. 2008;71:49-52. [PubMed] |