Published online Jun 16, 2011. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v3.i6.124

Revised: April 13, 2011

Accepted: May 4, 2011

Published online: June 16, 2011

In this report, a patient had a previous diagnosis of cholangiocarcinoma with an extended cholecystectomy. Three years later, he was evaluated for recurrent ascites. The patient had several large volume paracentesis, without evidence of malignant cells. Subsequently, endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) with fine needle aspiration (FNA) of both lymph and omental nodules was utilized. While the lymph nodes were negative for malignancy, the omental nodule was interrogated with multiple antibodies and was found to be positive for neoplasia. EUS with FNA can safely be used in patients with cirrhosis to spare the patient invasive evaluation such as exploratory laparotomy (ex-lap) for diagnosis and staging of cholangiocarcinoma.

- Citation: Rial NS, Gilchrist KB, Henderson JT, Bhattacharyya AK, Boyer TD, Nadir A, Cunningham JT. Endoscopic ultrasound with biopsy of omental mass for cholangiocarcinoma diagnosis in cirrhosis. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2011; 3(6): 124-128

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v3/i6/124.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v3.i6.124

Cholangiocarcinoma (CCA) is an adenocarcinoma arising from the epithelial tissue of the intra-hepatic (10%), hepatic hilar (25%) or extrahepatic (65%) bile ducts[1]. Among gastrointestinal (GI) cancers, CCA is the most difficult to detect and diagnose with a 5 year survival of less than 5%[2]. Recently, endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) has emerged as an important modality in the diagnosis of CCA. EUS guided fine needle aspiration (FNA) has a specificity of 100%, and a sensitivity of 43%-86% depending upon the location of the cholangiocarcinoma[3]. The negative predictive value for EUS-FNA for cholangiocarcinoma is reported at 29%[4]. The additional benefit of EUS-FNA is to sample regional lymph nodes to stage the disease particularly in the context of liver transplant evaluation[3].

Herein is a unique case of ascites in a patient where EUS was extremely helpful in making the diagnosis of CCA. EUS spared the patient an ex-lap which has inherent risks related to general anesthesia, intubation, abdominal insufflation and biopsy of masses. EUS is especially helpful in noting differences in echogenicity between normal tissue, lymph and omental nodes as well as neoplasms. This distinction makes EUS a selective biopsy technique, where the pre-test probability is higher than for gross visualization during an ex-lap.

A 35-year-old Caucasian male was referred from a community hospital to University Medical Center (UMC) for evaluation of painless jaundice. He complained of darkening of skin and urine for two months. Laboratory tests showed an alkaline phosphatase of 265 U/L (38-126 U/L), aspartate aminotransferase (AST) 56 U/L (7-40 U/L), alanine aminotransferase (ALT) 70 U/L (7-40 U/L), total bilirubin of 25.6 mg/dL (0.2-1.0 mg/dL), INR of 1.0 and albumin of 3.6 g/dL (3.5-5.5 g/dL). As part of his work-up an abdominal ultrasound, an endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) and a liver biopsy were performed.

The ultrasound showed hypoechoic tissue in the gallbladder lumen with possible extension into the adjacent liver as well as intra- and extra-hepatic biliary dilation. The ERCP showed a stricture of the left and right intra-hepatic ducts and a dilated left intra-hepatic duct. Bile duct brushings and biopsies were obtained and showed adenocarcinoma. The liver biopsy showed changes suggestive of intrahepatic-cholestasis. The patient was spared an ex-lap and was referred to surgical oncology.

An extended cholecystectomy comprising cholecystectomy, central hepatectomy and partial resection of segment IV of the liver was performed. The resected liver specimen showed cholangiocarcinoma within a background of cirrhosis. The tumor was present on the resected surgical margin and although the lymph nodes were negative for malignancy, the patient was subsequently treated with 5-Fluoro-uracil and radiotherapy (up to 54 Gy) using Capecitabine as a radiosensitizer. He received two months of concurrent radiation and chemotherapy. Thereafter, his laboratory and clinical parameters improved.

Three years later, the patient presented with recurrent ascites. He required large volume (9-12 liters) paracentesis every two weeks for 5 mo. His peritoneal fluid tested negative for malignancy on five different occasions. A liver transplant was considered and an EUS was done to evaluate the patient for possible candidacy.

A physical exam was performed prior to the endoscopic procedure. Informed consent was obtained from the patient after explanation of the risks of the procedure such as perforation, bleeding, infection, and adverse medication effects as well as the benefits of the procedure and alternatives. The patient was then connected to monitoring devices and placed in the left lateral position, After general anesthesia was achieved, the patient was intubated and the endoscope was advanced to the pylorus under direct visualization. The pylorus was identified by visual landmarks.

The linear echo endoscope GF-UE 160 1700564#60 (Olympus Corp. Lake Success, New York) was used to obtain biopsies. Hypoechoic lymph nodes were biopsied with fine needle aspiration (FNA) using a Cook (Winston Salem, North Carolina) 25 Guage needle. The FNA biopsies were collected and processed for immunohistochemistry (IHC).

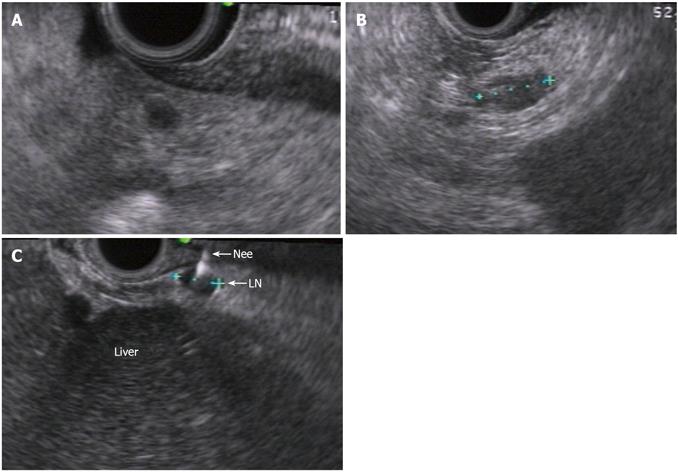

EUS identified a group of para-aortic (10 mm × 8 mm) and hilar lymph nodes (up to 5 mm) (Figure 1). The FNA of the para-aortic lymph node was negative. The EUS was repeated two weeks later and in addition to previously sampled lymph node (Figure 2A, 2B), small omentum nodules were also seen (Figure 3A, 3B). FNA was performed on these nodules as well as on the para-aortic lymph nodes using a 25-Guage needle.

The tissue samples were paraffin embedded, cut into 4 μm sections and mounted onto glass slides. Antibodies utilized were; carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) monoclonal antibody (Cat# 760-2507, Ventana Medical Systems), CEA polyclonal rabbit anti-human antibody (Cat# AO-115, DakoCytomation, Denmark), Cytokeratin 19 (Cat# 760-4281, Ventana Medical Systems) and Wilm’s Tumor 1 (WT1) (Cat# 348M-94, Cell Marque, Rocklin, CA).

Images were obtained in RGD TIFF format using a Nikon TE300 inverted microscope with 10x plan apo objective lens using a Coolsnap digital camera (Princeton Instruments, Trenton, NJ).

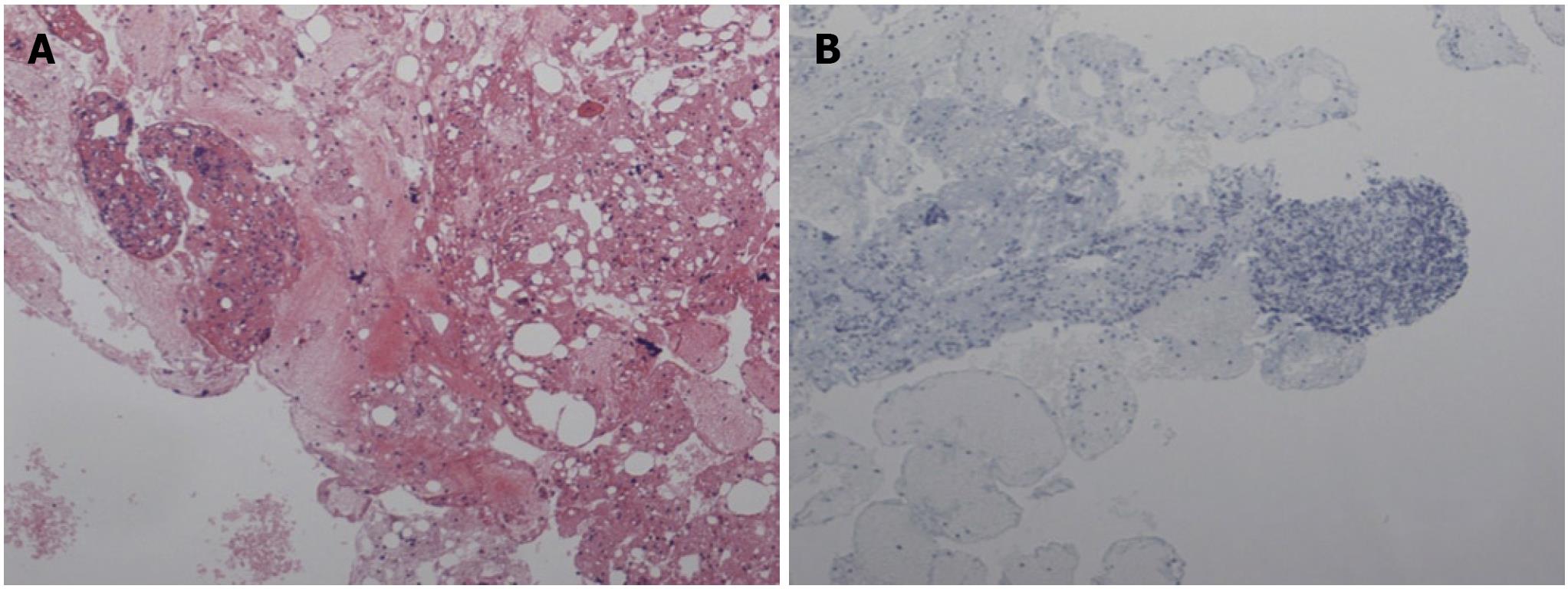

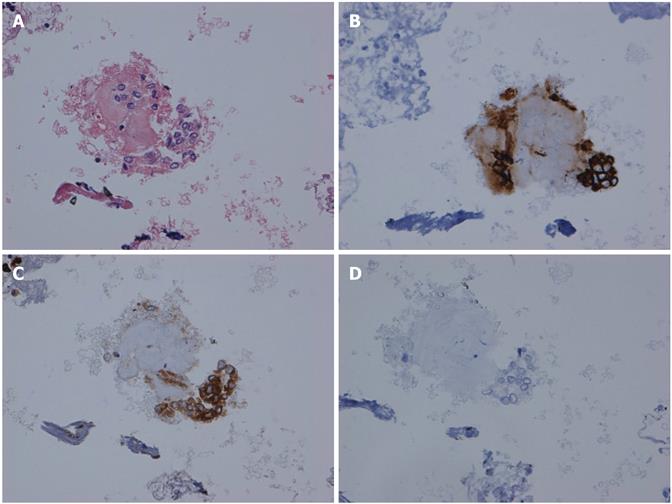

The lymph node did not show any abnormal cells and did not stain with cytokeratin-19 (Figure 2B). By contrast, the omental nodule was not normal. It did not show any lymphocytes thereby confirming its peritoneal origin. A group of abnormal cells was seen within the omental nodule. The abnormal cluster was stained with cytokeratin-19 and carcinogenic embryonic antigen (CEA). The results of the immunohistochemistry (IHC) showed abnormal epithelial cells consistent with CCA by cytokeratin-19 staining (Figure 3B, 3C). The omental nodule stained negative for WT1 (a marker for mesenchymal tissue) (Figure 3D). Thereby the IHC confirmed that the omental nodule was peritoneal in origin, abnormally positive for oncologic markers, and negative for mesenchymal markers.

All further evaluation for liver transplantation including exploratory laparotomy was stopped. The patient was spared the further evaluation and did not undergo an ex-lap.

This is the first reported case of EUS-FNA of an omental nodule in a patient with cirrhosis used to make the diagnosis of cholangiocarcinoma. It is significant because it helps to expand the use of EUS in clinical practice and has broad implication for the field at large. This case highlights that in patients with CCA and cirrhosis, omental metastasis can be sampled even when lymph nodes are negative.

In the case, despite a negative lymph node-FNA, a small omental nodule was positive for cytokeratin-19, consistent with CCA. The pathology report was initially “negative for malignancy” as mesothelial cells were reported in both the lymph nodes (Figure 2) and the omental nodule (Figure 3A and B). However at the Quality Assurance meeting, a small cluster of cells in the omental nodule was deemed suspicious and was thereafter stained with cytokeratin-19 and CEA. The omental nodule stained positive for cytokeratin-19, while the lymph node was negative.

This case highlights several points. First, that EUS is a safe and valuable tool in establishing the diagnosis of CCA. Second EUS with FNA can be used to stage CCA in patients with cirrhosis. EUS-FNA has been successfully used for the staging of CCA before consideration of liver transplantation[3-7]. EUS-FNA has been extensively used to biopsy the bile duct, gallbladder[5,6], hepatic hilum[7], regional lymph nodes[8] pancreatic lesions[9] and hepatic lesions[10] as well as for aspiration of malignant ascites[11]. Computed tomography (CT)-guided FNA has been utilized to biopsy peritoneal and omental masses[12]. This case highlights the difficulties encountered while managing patients with cholangiocarcinoma and cirrhosis[13,14].

This is novel because it is the first report of FNA-EUS guided omental nodule in the setting of CCA. In addition, one report suggested that peritoneal seeding of CCA occurred during percutaneous biliary drainage[15]. This indicates a mechanism for the spread of cancer cells through the contamination of the peritoneal cavity with malignant cells and increases suspicion of cholangiocarcinoma in a broad context of diseases[16,17]. Routine imaging studies can miss lesions of cholangiocarcinoma[6]. Many inoperable cases of cholangiocarcinoma have been excluded for liver transplantation after undergoing EUS that identified lesions previously not identified with other imaging modalities[7,18]. As a result EUS has become a routine procedure for patients with cholangiocarcinoma who are considered for liver transplantation.

Peer reviewers: Fauze Maluf-Filho, MD, Hospital das Clínicas, São Paulo University School of Medicine, 488 Olegario Mariano, São Paulo, Brazil

S-Editor Wang JL L-Editor Hughes D E-Editor Zhang L

| 1. | Lim JH. Cholangiocarcinoma: morphologic classification according to growth pattern and imaging findings. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2003;181:819-827. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Mosconi S, Beretta GD, Labianca R, Zampino MG, Gatta G, Heinemann V. Cholangiocarcinoma. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2009;69:259-270. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Harewood GC. Endoscopic tissue diagnosis of cholangiocarcinoma. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2008;24:627-630. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Rauws EA, Kloek JJ, Gouma DJ, Van Gulik TM. Staging of cholangiocarcinoma: the role of endoscopy. HPB (Oxford). 2008;10:110-112. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Meara RS, Jhala D, Eloubeidi MA, Eltoum I, Chhieng DC, Crowe DR, Varadarajulu S, Jhala N. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided FNA biopsy of bile duct and gallbladder: analysis of 53 cases. Cytopathology. 2006;17:42-49. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Eloubeidi MA, Chen VK, Jhala NC, Eltoum IE, Jhala D, Chhieng DC, Syed SA, Vickers SM, Mel Wilcox C. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration biopsy of suspected cholangiocarcinoma. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;2:209-213. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Fritscher-Ravens A, Broering DC, Sriram PV, Topalidis T, Jaeckle S, Thonke F, Soehendra N. EUS-guided fine-needle aspiration cytodiagnosis of hilar cholangiocarcinoma: a case series. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;52:534-540. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Gleeson FC, Rajan E, Levy MJ, Clain JE, Topazian MD, Harewood GC, Papachristou GI, Takahashi N, Rosen CB, Gores GJ. EUS-guided FNA of regional lymph nodes in patients with unresectable hilar cholangiocarcinoma. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;67:438-443. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Hahn M, Faigel DO. Frequency of mediastinal lymph node metastases in patients undergoing EUS evaluation of pancreaticobiliary masses. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;54:331-335. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Nakano T, Tahara-Hanaoka S, Nakahashi C, Can I, Totsuka N, Honda S, Shibuya K, Shibuya A. Activation of neutrophils by a novel triggering immunoglobulin-like receptor MAIR-IV. Mol Immunol. 2008;45:289-294. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Kaushik N, Khalid A, Brody D, McGrath K. EUS-guided paracentesis for the diagnosis of malignant ascites. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;64:908-913. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Souza FF, Mortelé KJ, Cibas ES, Erturk SM, Silverman SG. Predictive value of percutaneous imaging-guided biopsy of peritoneal and omental masses: results in 111 patients. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2009;192:131-136. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Maggs J, Cullen S. Management of autoimmune liver disease. Minerva Gastroenterol Dietol. 2009;55:173-206. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Saich R, Chapman R. Primary sclerosing cholangitis, autoimmune hepatitis and overlap syndromes in inflammatory bowel disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:331-337. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Miller GA, Heaston DK, Moore AV, Mills SR, Dunnick NR. Peritoneal seeding of cholangiocarcinoma in patients with percutaneous biliary drainage. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1983;141:561-562. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Elfaki DH, Gossard AA, Lindor KD. Cholangiocarcinoma: expanding the spectrum of risk factors. J Gastrointest Cancer. 2008;39:114-117. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Krawitt EL. Clinical features and management of autoimmune hepatitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:3301-3305. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Fritscher-Ravens A, Broering DC, Knoefel WT, Rogiers X, Swain P, Thonke F, Bobrowski C, Topalidis T, Soehendra N. EUS-guided fine-needle aspiration of suspected hilar cholangiocarcinoma in potentially operable patients with negative brush cytology. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:45-51. [PubMed] |