Published online May 16, 2011. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v3.i5.101

Revised: April 22, 2011

Accepted: April 29, 2011

Published online: May 16, 2011

A 66-year-old man developed dysphagia during dinner and was evaluated 2 d later in our hospital because of persistent symptoms. Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy showed no impacted food, but advanced esophageal cancer was suspected based on the presence in the upper esophagus of a large irregular ulcerative lesion with a thick white coating and stenosis. Further imaging studies were performed to evaluate for metastases, revealing circumferential esophageal wall thickening and findings suggestive of lung and mediastinal lymph node metastases. However, dysphagia symptoms and the esophageal ulcer improved after hospital admission, and histopathological examination of the esophageal mucosa revealed only nonspecific inflammation. At the time of symptom onset, the patient had been eating stewed beef tendon (Gyusuji nikomi in Japanese) without chewing well. Esophageal ulceration due to steakhouse syndrome was therefore diagnosed. The lung lesion was a primary lung cancer that was surgically resected. Although rare, steakhouse syndrome can cause large esophageal ulceration and stenosis, so care must be taken to distinguish this from esophageal cancer.

- Citation: Enomoto S, Nakazawa K, Ueda K, Mori Y, Maeda Y, Shingaki N, Maekita T, Ota U, Oka M, Ichinose M. Steakhouse syndrome causing large esophageal ulcer and stenosis. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2011; 3(5): 101-104

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v3/i5/101.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v3.i5.101

Steakhouse syndrome is a condition in which food impaction of the esophagus occurs after eating a piece of food, especially a meat bolus, without adequate chewing[1]. The symptoms, clinical presentation and endoscopic findings of steakhouse syndrome require differentiation from other esophageal disorders, and must be considered in patients complaining of dysphagia. We report herein a case of steakhouse syndrome causing esophageal ulceration and stenosis that had to be distinguished from esophageal cancer. We also compare the findings with 4 previous steakhouse syndrome cases that we have treated.

A 66-year-old man could not eat or drink anything during dinner (day 1 of onset). Due to persistent dysphagia, he was evaluated late at night in an urgent care center (day 2). The physician on duty diagnosed possible esophageal cancer and recommended gastroenterology consultation. After the patient returned home, dysphagia continued without improvement in the ability to eat, so he was evaluated 2 d later at our hospital (day 3). The patient had no history of specific diseases, and his family history was unremarkable. Lifestyle history included smoking 25 cigarettes/d for 46 years, but no regular alcohol intake.

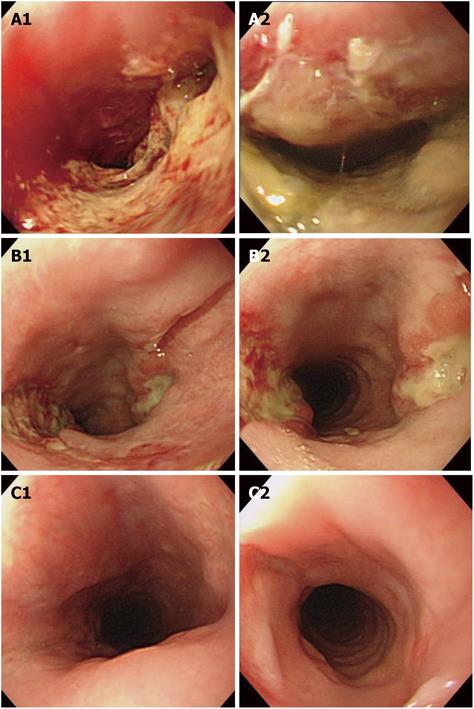

Blood tests at the time of evaluation showed leukocytosis (white blood cells, 16 800/mm3) and a mild inflammatory reaction (C-reactive protein, 2.9 mg/dL). Emergency endoscopy performed the same day revealed an irregular ulcerated lesion with a thick white coating in the upper esophagus (16 cm from the incisors) extending 4 cm longitudinally (Figure 1A). The lesion occupied about two-thirds of the circumference of the esophageal lumen. No solid food impaction was observed in this area. Esophageal stenosis was evident. Insertion of the scope distal to the lesion was difficult, but possible.

Endoscopic examination of the esophageal ulcer showed no surrounding ridge or distinct elevation but, because of the ulcer size and extension, irregular ulcer margins, esophageal stenosis, edematous surrounding mucosa and friability, advanced esophageal cancer was suspected. Endoscopic biopsy of the ulcer margins was therefore performed. Distal to the lesion in the mid and lower esophagus, no esophagitis or other findings were observed. The only finding noted in the stomach was atrophic gastritis. As the patient had difficulty eating, he was admitted to our hospital. No fever or chest pain was apparent but, because of the inflammation, the patient was placed on a nil-by-mouth regimen and given intravenous fluids with antibiotics.

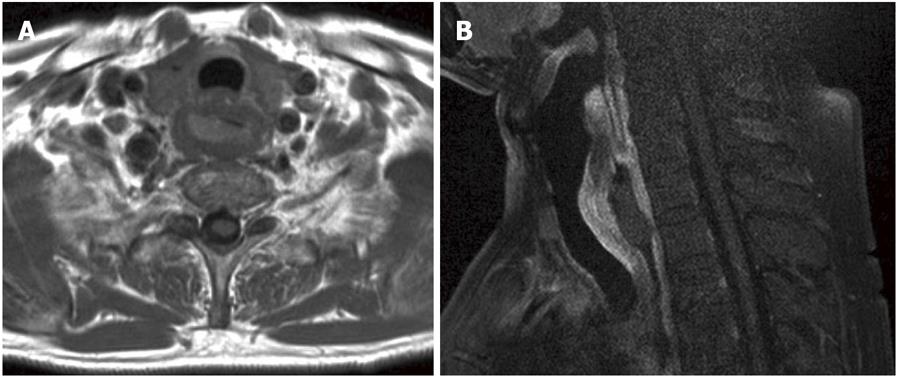

Further evaluation was performed on admission for a suspected diagnosis of advanced esophageal cancer. Tumor markers carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA; 13.8 ng/mL) and carbohydrate antigen 19-9 (CA19-9; 38 U/mL) were elevated. Cytokeratin 19 fragment (CYFRA; 1.2 ng/mL) was within normal limits. Chest magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed circumferential wall thickening in the cervical esophagus, and gadopentate dimeglumine (Gd-DTPA) enhanced MRI showed a contrast effect (Figure 2A and B). In the right lung apex, enhanced MRI revealed a 2-cm nodule with contrast enhancement. This lesion could not be identified on chest radiography because of overlap with the superior mediastinum and an indistinct appearance. Positron emission tomography/computed tomography using F-18 fluoro-deoxy-glucose (FDG PET/CT) was performed to exclude systemic metastasis due to esophageal cancer. This showed circumferential wall thickening of the cervical esophagus, with abnormal uptake of FDG in this area [Standardized uptake value (SUV) max = 4.8]. FDG PET/CT also showed the 2-cm nodule in the right lung apex, with abnormal uptake of FDG in the same area (SUV max = 7.1). In addition, abnormal FDG uptake was seen in the bronchial and anterior mediastinal lymph nodes and lymph node metastases were suspected. No metastases were found in other distant organs. At this point, the differential diagnosis had to include esophageal cancer with lung metastases or multiple primary esophageal and lung cancers.

However, histopathology of the esophageal biopsy revealed only nonspecific inflammation, and dysphagia improved during hospitalization. A second endoscopy was therefore performed on day 9. This showed deep ulceration with a white coating at the 3 and 9 o’clock positions in the lumen, although the ulceration was smaller, and stenosis of the esophageal lumen had improved (Figure 1B). A third endoscopy was performed on day 23. The white coating had disappeared, and the esophageal ulcer had healed and scarred (Figure 1C). When the patient was asked again about what he was eating when the symptoms developed, he confirmed having swallowed a piece of “stewed beef tendon (Gyusuji nikomi in Japanese)” without sufficient chewing before the onset of dysphagia. Beef tendon is a tough meat and is used as a food in some Asian countries, including Japan. Furthermore, the impacted food was not extracted by vomiting and was spontaneously swallowed. However, dysphagia continued without improvement in the ability to eat. Based on this, esophageal ulcer associated with steakhouse syndrome was diagnosed. With regard to the right lung lesion, primary lung cancer was diagnosed, and right upper lobectomy was performed. The histopathological diagnosis was mixed-type adenocarcinoma. Tumor markers have normalized, and the patients’ clinical course has been good.

Steakhouse syndrome, first reported by Norton et al[1] in 1963, is caused by food impaction in the esophagus. Examination of the upper gastrointestinal tract for a foreign body often reveals a true foreign body in younger patients, whereas food bolus is more common in older patients[2,3]. When endoscopy reveals solid food impaction, an endoscopic polypectomy snare or grasping forceps can be used for extraction. If a fragmenting meat bolus is identified, a push technique can be performed[2,4].

Table 1 lists the details of 5 cases of steakhouse syndrome that we have treated, including the present case. In our previous 4 cases, emergency endoscopy showed food impaction, and the impacted food was treated endoscopically. None of the previous 4 patients displayed esophageal ulceration. However, in the present patient, endoscopic findings differed from those in the previous 4 cases, warranting differential diagnosis from esophageal cancer. These findings were: 1) absence of obvious impacted food on initial endoscopy; 2) large esophageal ulceration; and 3) edematous esophageal mucosa with severe lumen stenosis.

| Case | Age (years) | Causative food | Location | Endoscopic findings | Therapy |

| 1 | 78 | Beef steak | Upper esophagus | Food impaction | Food extracted with grasping forceps |

| 2 | 17 | Chicken steak | Middle esophagus | Food impaction | Food pushed into stomach with endoscope tip |

| 3 | 51 | Beef steak | Upper esophagus | Food impaction | Food extracted with grasping forceps |

| 4 | 85 | Apple | Upper esophagus | Food impaction, erosion | Food pushed into stomach after fragmenting with grasping forceps |

| 5 (present report) | 66 | Stewed beef tendon | Upper esophagus | Esophageal ulcer, stenosis | NPO and intravenous fluids |

One reason for the ulcer formation may be the particular patient history in this case. Namely, the previous 4 patients were evaluated on the same day or the day after onset of food impaction symptoms. However, the current patient was evaluated at our hospital 3 d after symptom onset, thereby delaying endoscopy. Delaying endoscopic removal of food impaction risks the possibility of esophageal perforation or respiratory impairment[2,3], and large esophageal ulcers, as seen in our patient, have almost never been reported in steakhouse syndrome. Even among case reports in which evaluation has continued for some time after the onset of food impaction symptoms, only shallow geographic ulcers have been reported[5], but esophageal ulcers were absent in many cases[6]. In 4 of our 5 cases, including this patient, meat was the cause of impaction. Similarly, the site of food impaction was the upper esophagus in 4 cases. The method of cooking the meat-roast (3 previous patients) or stew (current patient) differed, but whether this had any effect on ulcer formation is unclear.

In this case, we concluded that the esophageal ulcer resulted from some mechanism due to food impaction, but we cannot exclude the possibility of a reverse phenomenon in which an esophageal ulcer formed first for some reason, followed by food impaction at the site where esophageal stenosis had developed. As possible causes for esophageal food impaction, several underlying obstructive lesions should be considered. These include esophageal webs and rings[1,7], esophageal hiatal hernia[8], reflux esophagitis with stricture[9], postoperative anastomotic strictures[7], and malignant lesions[9,10]. However, in this case, a malignant etiology was excluded and, because no erosions, ulcers, or inflammation were present in the mid or lower esophagus, reflux esophagitis in the upper esophagus was considered unlikely. In addition, given the ulcer characteristics and healing process, a specific type of esophagitis or ulceration, such as viral or fungal, was also unlikely. Pill-induced esophageal ulcers are fairly common. The lesion is mainly due to entrapment of the pill and /or its chemical composition. However, in this case, the patient did not take any prescribed medication. Furthermore, since no food impaction in the esophagus was proven in this case, the diagnosis of steakhouse syndrome seemed uncertain. As mentioned above, other diseases that might cause an esophageal ulcer were ruled out. This case may have developed due to both food impaction coupled to a thermal burn at the site,causing such a severe ulceration with stenosis to develop in just 3 d.

In conclusion, we have reported a case of steakhouse syndrome, which should be considered in the differential diagnosis for patients complaining of dysphagia. Although rare, extensive esophageal ulceration and stenosis due to food impaction, as seen in this patient, can occur. Findings of food impaction may thus be missed on endoscopy. Unless the physician elicits a careful history, the patient may fail to mention anything about what they ate. Thus, in steakhouse syndrome, a careful history at initial evaluation is very important, particularly regarding food type and characteristics, circumstances surrounding ingestion, and time of ingestion.

Peer reviewers: Mitsuhiro Asakuma, MD, PhD, Assistant Professor, Department of General and Gastroenterological Surgery, Osaka Medical College, 2-7 Daigaku-machi, Takatsuki, Osaka 569-8686, Japan; David J Desilets, MD, PhD, Chief, Division of Gastroenterology, Springfield Bldg, Rm S2606, Department of Medicine, Assistant Professor of Clinical Medicine, Tufts University School of Medicine, Springfield Campus, Baystate Medical Center, Springfield, MA 01199, United States

S- Editor Wang JL L- Editor Hughes D E- Editor Zhang L

| 1. | Norton RA, King GD. “Steakhouse Syndrome“: The Symptomatic Lower Esophageal Ring. Lahey Clin Found Bull. 1963;13:55-59. |

| 2. | Webb WA. Management of foreign bodies of the upper gastrointestinal tract: update. Gastrointest Endosc. 1995;41:39-51. |

| 3. | Vizcarrondo FJ, Brady PG, Nord HJ. Foreign bodies of the upper gastrointestinal tract. Gastrointest Endosc. 1983;29:208-210. |

| 4. | Longstreth GF, Longstreth KJ, Yao JF. Esophageal food impaction: epidemiology and therapy. A retrospective, observational study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;53:193-198. |

| 5. | Nakajima H, Muramoto K, Sasaki H, Nara H, Sato K, Munakata A. A case of steakhouse syndrome presenting with ischemic electrocardiogram findings. Gastroenterological Endoscopy. 1999;41:2509-2513 (in Japanese with English abstract). |

| 6. | Chae HS, Lee TK, Kim YW, Lee CD, Kim SS, Han SW, Choi KY, Chung IS, Sun HS. Two cases of steakhouse syndrome associated with nutcracker esophagus. Dis Esophagus. 2002;15:330-333. |

| 7. | Rice BT, Spiegel PK, Dombrowski PJ. Acute esophageal food impaction treated by gas-forming agents. Radiology. 1983;146:299-301. |

| 8. | Trenkner SW, Maglinte DD, Lehman GA, Chernish SM, Miller RE, Johnson CW. Esophageal food impaction: treatment with glucagon. Radiology. 1983;149:401-403. |

| 9. | Hargrove MD, Jr . Boyce HW, Jr. Meat impaction of the esophagus. Arch Intern Med. 1970;125:277-281. |