Published online Mar 16, 2011. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v3.i3.62

Revised: December 25, 2010

Accepted: January 1, 2011

Published online: March 16, 2011

Pancreatitis in the elderly is a problem of increasing occurrence and is associated with severe complications. Periampullary diverticula (PAD) are extraluminal outpouchings of the duodenum rarely associated with pancreatitis. The presence of PAD should be excluded before diagnosing idiopathic pancreatitis, particularly in the elderly. However, when a duodenal diverticulum is found in the absence of any additional pathology, only then should the symptoms be attributed to the diverticulum. We describe a case of duodenal diverticulum presenting with pancreatitis to emphasize the importance of this commonly neglected etiology.

- Citation: Rizwan MM, Singh H, Chandar V, Zulfiqar M, Singh V. Duodenal diverticulum and associated pancreatitis: case report with brief review of literature. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2011; 3(3): 62-63

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v3/i3/62.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v3.i3.62

Duodenal diverticulum is a well known entity since the early eighteenth century when it was first reported by a French pathologist, Chomel, in 1710. The duodenum is the second most common site of diverticula in the small bowel following the jejunum[1,2]. It is difficult to ascertain the true prevalence of duodenal diverticula; they are seen in 1%-6% of upper gastrointestinal contrast studies[2,3], 12%-27% of endoscopic studies[2,4] and in 15%-22% of autopsies. Diverticula are rare below age 40 and the prevalence rate increases with age.

Diverticula occur at weak spots in the duodenal wall such as the site of entry of the common bile duct, pancreatic duct and perivascular connective tissue sheath. The exact etiology is not clear; however, it might be the end result of disordered duodenal motility. Advancing age, progressive weakening of intestinal smooth muscles and increase in intraduodenal pressure may all encourage the outpouching of the duodenum.

About 70%-75% of all duodenal diverticula are periampullary. Diverticula arising within 2-3 cm radius of the ampulla but not containing it are referred to as juxtapapillary diverticula. However, if the papilla arises within a diverticulum it is called an intradiverticular papilla. In the majority of cases, diverticula arise on the inner or pancreatic border of the duodenum. The possibly of PAD should be kept in mind while interpreting any bile duct imaging. It can create a filling defect in biliary passage; hence, can be mistaken for periampullary tumors or biliary stones. It can also be misinterpreted as pancreatic pseudocyst when it is large and fluid filled.

A 69 year old Caucasian male presented to our hospital because of worsening abdominal pain for 3 d. The pain was initially in the upper abdomen but later radiated to the back. Epigastric tenderness was evident on physical examination. He had a history of similar painful episodes occurring infrequently for a few years but the pain had never been so severe. He had never previously sought medical attention for this pain. He also had a past medical history of constipation, hemorrhoids, dementia and hypertension.

The patient was given nil per mouth while workup for abdominal pain was started. His pancreatic enzymes were found to be elevated and a subsequent CT scan showed an irregular pancreatic outline consistent with pancreatitis. Interestingly, CT of the abdomen showed gas collection in the pancreatic head which raised the suspicion of a duodenal diverticulum. Sigmoid diverticulum and a small inguinal hernia were also incidental findings on the CT scan. HIDA scan was performed which showed normal transit of bile through the common bile duct (CBD).

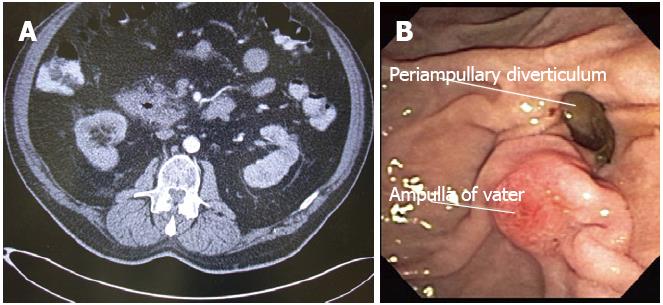

A subsequent ERCP showed a duodenal diverticulum with ampulla in the mouth of diverticulum (Figure 1A, B). There was no evidence of any CBD stones or strictures on cannulation of the CBD. No intervention was needed since the patient’s condition started to improve with conservative management and the patient was found to be doing well at his 1 year follow-up visit.

Pancreatitis in the elderly is a problem of increasing occurrence and is associated with severe complications. The possibility of the presence of PAD should be kept in mind in the differential of pancreatitis, particularly in the elderly population. In this patient, we believe chronic constipation was the factor responsible for hemorrhoids, sigmoid and duodenal diverticulum. The diverticulum might have been a major contributing factor in repeated attacks of mild self-resolving pancreatitis in the past.

With lengthening of the life span, diverticulosis has come to occupy a more important position in the sphere of clinical gastroenterology. The majority of duodenal diverticula are asymptomatic. Clinical presentation may be characterized by non-specific abdominal symptoms. However, complications are responsible for presentation in most cases. When drainage in the neck is inadequate or the neck is narrow, these conditions favor inflammation and may even lead to hemorrhage or perforation.

There have been anecdotal accounts implicating PAD in the pathogenesis of acute and chronic pancreatitis. Compression of CBD, dysfunction of the ampulla or a poorly emptying diverticulum with a narrow neck can all lead to pancreatico-biliary disease and possible pancreatitis. However, the relationship with pancreatitis remains tenuous as biliary calculus disease is also more common in PAD. It is debatable whether the pancreatitis is caused by the PAD per se or by the associated biliary calculi. It has been proposed that PAD may be responsible for transient biliary symptoms and alterations in liver function[5]. It is possible in the above mentioned case that distension of a diverticulum with inspissated food might have caused compression of the pancreatic duct leading to pancreatitis which resolved spontaneously.

To date, there are no hard and fast guidelines regarding management of such diverticulum. Earlier this century, surgical diverticulectomy was frequently carried out for non-specific symptoms. There is now consensus that elective surgical treatment of asymptomatic or minimally symptomatic diverticulum is not justified. Operative procedures for diverticula in the second part of duodenum are particularly cumbersome since often it requires mobilization of the duodenum which is retroperitoneal. Dennesen and Rijken reviewed 45 reported cases of perforation of duodenal diverticula and found an overall mortality rate of 31%[2]. Surgical or endoscopic interventions should only be reserved for symptomatic diverticulum[6]. Diverticulectomy for vague pain and abdominal discomfort is dangerous and unrewarding; it carries a high morbidity and mortality[3,6]. Furthermore, only 50% of patients treated with diverticulectomy were relieved of their symptoms [6,7].

Peer reviewers: Jiang-Fan Zhu, MD, Professor of Surgery, Department of General Surgery, East Hospital of Tongji University, Pudong, Shanghai 200120, China; Maher Aref Abbas, MD, FACS, FASCRS, Associate Professor of Surgery, Chief, Colon and Rectal Surgery, Center for Minimally Invasive Surgery, Kaiser Permanente, 4760 Sunset Blvd, third Floor, Los Angeles, CA 90027, United States; Wahid Wassef, MD, MPH, FACG, Professor of Medicine, Division of Gastroenterology, Department of Medicine, University Campus, 55 Lake Avenue, North, Worcester, MA 01655, United States

S- Editor Zhang HN L- Editor Roemmele A E- Editor Liu N

| 1. | Mahajan SK, Kashyap R, Chandel UK, Mokta J, Minhas SS. Duodenal diverticulum: Review of literature. In J Surg. 2004;66:140-145. |

| 2. | Dennesen PJ, Rijken J. Duodenal diverticulitis. Neth J Med. 1997;50:250-253. |

| 3. | Burgess CM, Ball J. Complications of surgery on duodenal diverticula. Surg Clin North Am. 1970;50:351-355. |

| 4. | Zoepf T, Zoepf DS, Arnold JC, Benz C, Riemann JF. The relationship between juxtapapillary duodenal diverticula and disorders of the biliopancreatic system: analysis of 350 patients. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;54:56-61. |

| 5. | Lobo DN, Balfour TW, Iftikhar SY, Rowlands BJ. Periampullary diverticula and pancreaticobiliary disease. Br J Surg. 1999;86:588-597. |