Published online Nov 16, 2011. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v3.i11.220

Revised: September 23, 2011

Accepted: October 18, 2011

Published online: November 16, 2011

AIM: To study the role of needle knife assisted ampullary biopsy in the diagnosis of periampullary carcinoma.

METHODS: In this study the authors retrospectively analyzed clinical records of patients with periampullary tumors diagnosed by ampullary biopsy taken after needle knife papillotomy in whom surface ampullary biopsies were non contributory.

RESULTS: Between January 2008 and December 2010, 38 patients with periampullary tumors were seen by us and initial side viewing endoscopy with surface biopsy from the papilla was positive for malignancy in 25 patients. Thirteen patients with a negative surface biopsy for malignancy underwent a repeat ampullary biopsy following needle knife papillotomy. There were 8 (61.5%) males and 5 (38.5%) females. The most common presenting symptom was jaundice (100%), followed by fever (46.2%), melena (38.5%), abdominal pain (30.8%) and weight loss (30.8%). All the patients had hyperbilirubinemia with a mean ± SD serum bilirubin of (11.2 ± 1.9) mg/dL (normal value < 1 mg%) and the mean ± SD serum alkaline phosphatase was (288.0 ± 94.3) IU/L (normal value < 129 IU/L). Serum CA 19.9 level estimation was done in 11 patients; it was elevated (cut off value > 70.5 IU/L) in all of them with a median of 1200 IU/L (inter quartile range 274-3500). Side viewing endoscopy showed a bulky papilla in all of them. Adequate tissue was obtained in all of the 13 patients for histological evaluation; 12 of the 13 patients were reported to have adenocarcinoma while one patient had adenoma. There were no complications from the needle knife papillotomy in any of the patients.

CONCLUSION: Needle knife assisted ampullary biopsy appears to be a safe and effective diagnostic modality for periampullary carcinoma.

- Citation: Noor MT, Vaiphei K, Nagi B, Singh K, Kochhar R. Role of needle knife assisted ampullary biopsy in the diagnosis of periampullary carcinoma. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2011; 3(11): 220-224

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v3/i11/220.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v3.i11.220

Periampullary tumors are defined as those arising within 2 cm of the major papilla. They include tumors of the ampulla of Vater, the distal common bile duct (CBD), duodenal tumors involving the papilla and tumors of the pancreatic head involving the papilla[1]. They are considered collectively because of their similar clinical presentation and difficulty in distinguishing them without examination of the resected specimen. Early and accurate diagnosis of periampullary carcinoma is important because the prognosis is generally much more favorable than pancreatic carcinoma after radical resection[2].

The mainstay of diagnosis of periampullary carcinoma is side viewing endoscopy with ampullary biopsy but only a few studies have assessed the role of endoscopic biopsy for the diagnosis of periampullary carcinoma[3-6]. The reported yield of endoscopic biopsies is limited[3-6]. A major reason for negative biopsies is the submucosal location of some of the tumors with no infiltration of the overlying mucosa. Surface biopsies with conventional forceps fail to get the desired tissue in such patients. Yamaguchi et al[4] have described three macroscopic types of ampullary tumors: intramural protruding, exposed protruding and ulcerating. In the intramural protruding variety, the yield of forceps biopsies is the least. It has been suggested that a prior sphincterotomy can help expose the submucosal tumor in such patients[6,7]. Using the same logic, we used needle knife papillotomy to take biopsies from intramural protruding periampullary tumors. Moreover, in some cases the carcinoma is within an adenoma and the surface biopsy may diagnose only the benign lesion. Few studies have shown increased diagnostic yield with post sphincterotomy deeper papillary biopsies[6,7]. The aim of the present study is to report our experience of papillary biopsy taken after needle knife incision.

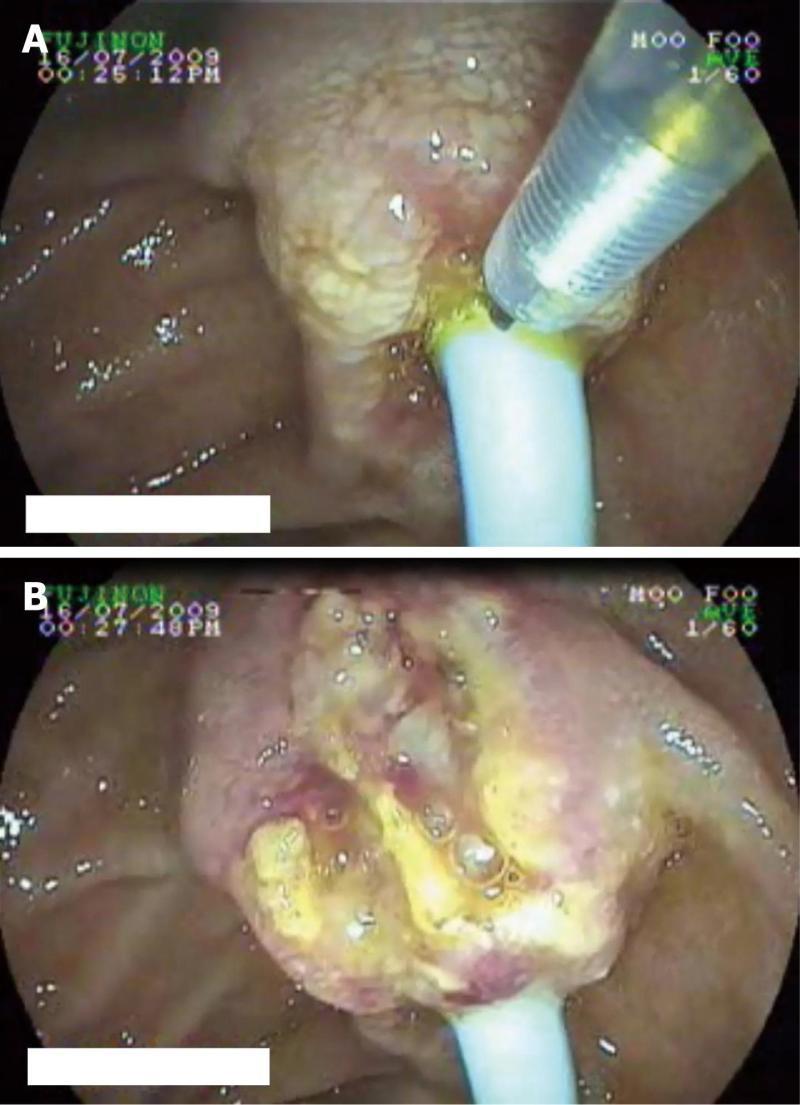

Between January 2008 and December 2010, all patients with extrahepatic biliary obstruction referred to our hospital were subjected to detailed evaluation in the form of liver function tests, tumor marker (CA 19.9), ultrasound abdomen and contrast enhanced computed tomography (CECT) of the abdomen. Detailed clinical profile was noted. Cut off value for serum CA 19.9 was 70.5 U/mL[8]. Coagulation parameters including prothrombin index and platelet count were checked in all the patients. Patients suspected of having periampullary carcinoma underwent side viewing endoscopy and ampullary biopsy using standard biopsy forceps (RBF-2.4-160, Olympus Corp, Tokyo, Japan). Patients with negative surface biopsy of papilla for malignancy underwent a repeat endoscopic biopsy from the papilla following needle knife incision of the papilla. The incision was made either from the ampullary orifice upwards towards 12 o’clock or from the most prominent part of ampulla along the 12 o’clock position downwards towards the opening. As the incision was made and the superficial tissue retracted, the underlying tissue was exposed. The depth of the incision was increased until the tumor was clearly visible. In patients who already had a biliary stent in situ, the stent was used to guide the incision starting at the ampullary orifice and the incision was extended depth wise till the stent was exposed. In patients with jaundice and without a stent in situ, the needle knife incision was extended to assess the bile duct and a flexible 0.035” guidewire (Hydra Jag, Boston Scientific Co., Marlborough, Mass, United States) was placed under fluoroscopic guidance. A biliary stent was placed over the guidewire in such patients. All the side viewing endoscopies with surface as well as needle knife assisted biopsies were obtained by a single experienced endoscopist using Fujinon duodenoscope (ED 4400, Fujinon Co., Saitama, Japan) and the needle knife incision was made by using a triple lumen needle knife sphincterotome (Micro-knife XL®, Boston Scientific Co., Marlborough, Mass, United States). Patients with gastric outlet obstruction and those who did not consent for the procedure were excluded. All the patients were observed for 6 h in the hospital for bleeding, pain, tenderness and drop in blood pressure. They were reviewed the next day in the outpatient department and those with any complications were admitted. The formalin-fixed tissue was embedded in paraffin and sections were stained with hematoxylin-eosin. Histological interpretation of the biopsy specimen was done by a single experienced histopathologist (Vaiphei K). Informed written consent was obtained from each patient and the study was approved by the Institute Ethics committee.

Parametric quantitative variables were expressed as mean ± SD and non parametric quantitative variables were expressed as median with inter quartile range (IQR). Categorical variables were expressed as percentages. Statistical analysis was performed using the statistical software package SPSS version 17.0 (SPSS, Chicago, Illinois, United States).

Between January 2009 and December 2010, 38 patients were suspected to have periampullary carcinoma on the basis of initial work up. Initial side viewing endoscopy with surface biopsy from the papilla was positive for malignancy in 25 patients. Thirteen patients with negative surface papillary biopsy for malignancy underwent repeat ampullary biopsy following needle knife papillotomy, which was positive in 12 of them.

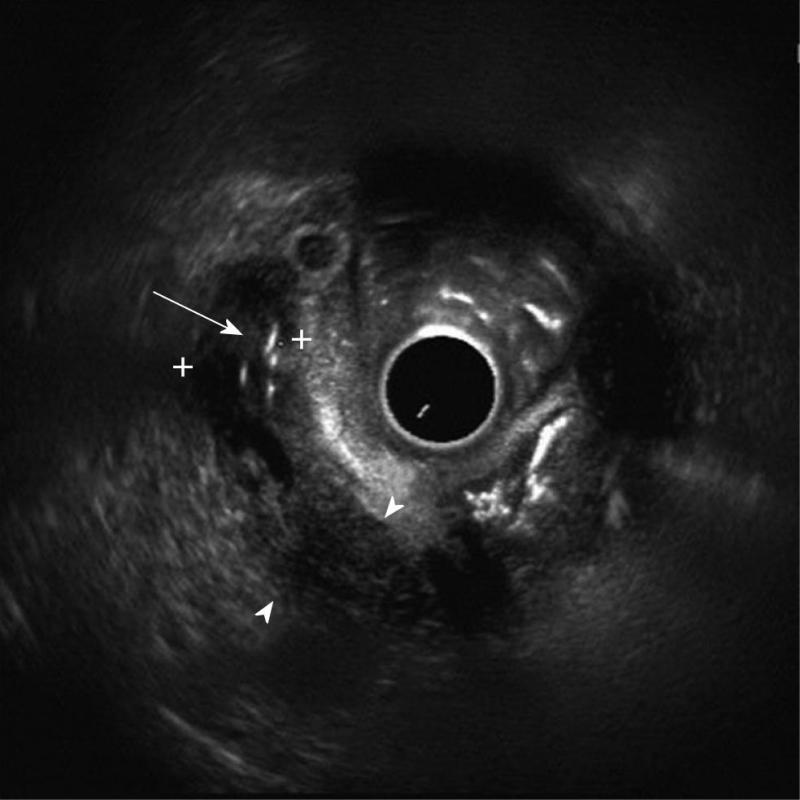

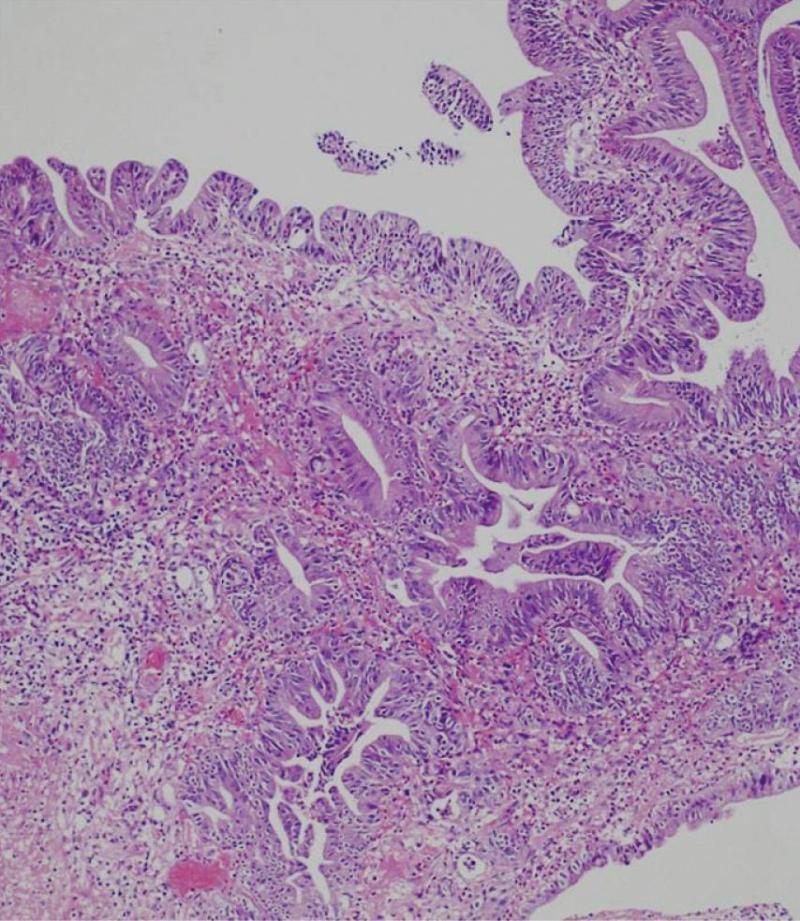

Details of the patients who underwent needle knife assisted papillary biopsy are given in Table 1. Mean ± SD age of the patients was (62.3 ± 9.6) years. There were 8 (61.5%) males and 5 (38.5%) females. All the patients (100%) presented with jaundice, 6 (46.2%) had a history of fever, 5 (38.5%) had melena, 4 (30.8%) had abdominal pain and 4 (30.8%) had significant weight loss. Nine (69.2%) patients were anemic with hemoglobin < 12 gm/dL. All the patients had hyperbilirubinemia with a mean ± SD serum bilirubin of (11.2 ± 1.9) mg/dL (normal value < 1 mg%) and mean ± SD serum alkaline phosphatase was (288.0 ± 94.3) IU/L (normal value < 129 IU/L). Serum CA 19.9 level estimation was done in 11 patients and was elevated (>70.5 U/mL) in all of them with a median of 1200 IU/L (IQR 274-3500). Ultrasound of the abdomen showed a dilated CBD and main pancreatic duct (MPD) in 9 (69.2%) and only dilated CBD in 4 (30.8%). Side viewing endoscopy in all of them showed a bulky papilla fitting the description of intramural protruding type of tumor as per Yamaguchi’s classification[4]. In 5 patients, the stent was already in situ, while in 8 patients the stent was placed after needle knife incision (Figure 1). A CECT abdomen was available in all the patients and it showed dilated CBD and MPD in 10 (76.9%) patients and only dilated CBD in 3 (23.1%) patients; a definite mass was demonstrated in 10 patients (76.9%) (Figure 2). The tumor was resectable in 9 (69.2%) patients and it was unresectable in 4 (30.8%) patients. Endoscopic ultrasonography was done in the last 3 (23.1%) patients, showing a small periampullary mass in all of them (Figure 3). Adequate tissue was obtained in all 13 patients for histological evaluation; 12 of the 13 patients were reported to have adenocarcinoma (Figure 4) and one had adenoma. The diagnosis of adenocarcinoma was confirmed at histopathological examination of the resected specimen or fine needle aspiration cytology from the metastasis. There were no complications from the needle knife papillotomy in any of the patients.

| Case | Age (yr)/gender | Presentation | GB mass | Hb (gm/dL) | TLC (/mm3) | Serum bilirubin (mg/dL) | ALP (IU/L) | CA 19.9 (U/mL) | Post needle knife biopsy | Stent |

| 1 | 75/female | Jaundice,weight loss | + | 11.0 | 8800 | 11.0 | 312 | NA | Adeno CA | + |

| 2 | 54/male | Jaundice, melena | - | 12.0 | 7400 | 8.0 | 274 | 274 | Adeno CA | - |

| 3 | 42/male | Jaundice, pain abdomen | + | 11.2 | 9400 | 12.5 | 310 | 430 | Adeno CA | + |

| 4 | 65/female | Jaundice, fever | + | 11.5 | 12 100 | 15.5 | 471 | 780 | Adeno CA | - |

| 5 | 58/male | Jaundice, weight loss | - | 13.0 | 9400 | 10.5 | 321 | 1408 | Adeno CA | - |

| 6 | 71/male | Jaundice, melena | + | 9.2 | 12 000 | 9.2 | 475 | 2900 | Adeno CA | - |

| 7 | 54/male | Jaundice, fever | + | 9.5 | 13 400 | 11.2 | 274 | 1451 | Adeno CA | - |

| 8 | 61/female | Jaundice, pain abdomen, fever | + | 7.8 | 11 400 | 9.5 | 183 | 714 | Adeno CA | - |

| 9 | 63/male | Jaundice, pain abdomen, melena | + | 8.1 | 12 400 | 9.9 | 274 | 1121 | Adeno CA | + |

| 10 | 68/male | Jaundice, pain abdomen,weight loss | - | 12.2 | 7800 | 11.5 | 210 | 3500 | Adeno CA | + |

| 11 | 63/female | Jaundice, fever, weight loss | + | 11.5 | 8500 | 12.5 | 194 | 1200 | Adenoma | - |

| 12 | 58/male | Jaundice, fever, melena | + | 12.5 | 9900 | 11.2 | 248 | NA | Adeno CA | - |

| 13 | 75/female | Jaundice, fever, melena | - | 7.5 | 13 500 | 13.0 | 198 | 3400 | Adeno CA | + |

We have described the role of needle knife assisted ampullary biopsies in the diagnosis of periampullary carcinoma. A positive diagnosis of adenocarcinoma was obtained in 12 of the 13 patients who had a negative surface biopsy earlier. There were no procedure related complications in any patients. The sensitivity of forceps biopsies for the diagnosis of periampullary carcinoma ranges from 21 to 81% in different studies[3,4,9,10]. The sensitivity of ampullary biopsy depends on the gross appearance of the tumor; Yamaguchi et al[4] reported biopsy positivity of 50% in intramural protruding type, 64% in the exposed protruding type and 88% in the ulcerating type.

As the yield of ampullary surface biopsy in the diagnosis of periampullary carcinoma is limited, different techniques have been used to take a deeper biopsy. A tumor arising inside the ampulla can produce a bulge with normal overlying duodenal mucosa which can mimic an impacted stone. Huibregtse et al[9] reported that snare biopsy improved the tissue quality and improved the diagnostic yield from 60% to 83% in such patients. Other studies have suggested an increase in sensitivity following sphincterotomy. Menzel et al[6] reported improvement in the accuracy of ampullary biopsy following sphincterotomy in the diagnosis of ampullary tumors from 63% to 70% overall and from 21% to 37% for carcinoma. In their series, 12 out of 19 carcinomas were missed even after sphincterotomy. Ponchon et al[7] also reported increased yield of ampullary biopsy after sphincterotomy; biopsies were taken on the day of sphincterotomy in 9 patients and 10 d to 4 wk later in 22 patients. In 4 patients whose biopsies were normal or non interpretable at the time of sphincterotomy, it was observed that biopsies taken 10 d later showed an ampullary tumor in all of them. They suggested that endoscopic sphincterotomy makes interpretation of biopsy specimens difficult as a result of the thermal effect on tissue, often leading to negative results. So they recommended that a biopsy should be taken 2 to 10 d after sphincterotomy[7,10].

Needle knife papillotomy is an improvement over previous techniques. A smooth bulky papilla can be incised and the tumor exposed. In contrast to a sphincterotomy, needle knife incision of the papilla only cuts the superficial layers of papilla and leads to a minimal thermal effect on deeper tissue so biopsies can be taken at the same time. There were no procedure-related complications recorded in any of our patients, suggesting that needle knife assisted biopsy is a safe technique in expert hands. In addition to a biopsy, needle knife papillotomy also helps to gain access to the bile duct to provide endoscopic biliary drainage. Surface biopsy diagnosis of adenoma does not rule out the possibility of underlying carcinoma, as reported by Seifert et al[11] in 30% of their patients with papillary adenoma. Needle knife assisted biopsy rules out this possibility by sampling a deeper tissue specimen.

Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) is an important recent diagnostic modality in the detection of small periampullary tumors. Shoup et al[12] found EUS to be more sensitive although less specific than computed tomography (CT) in the detection of periampullary tumors; EUS was 90% accurate for detecting tumors smaller than 2 cm compared with 70% for CT scan. EUS images of periampullary tumors correspond well with the histological findings[13]. EUS guided fine needle aspiration can be used to take cytological samples in periampullary tumors but it is technically demanding as positioning the scope and needle insertion are difficult.

To conclude, needle knife assisted ampullary biopsy appears to be a safe and effective diagnostic modality in the diagnosis of periampullary tumors, particularly in those patients who have an intramural protruding type of tumor as per Yamaguchi’s classification[4]. A prospective study to validate the role of needle knife assisted ampullary biopsy in different morphological types of periampullary masses is needed to establish its role on a larger scale.

Endoscopic biopsy is the mainstay of diagnosis of periampullary carcinoma but the yield of surface ampullary biopsy is limited. This study was conducted to evaluate the role of needle knife assisted ampullary biopsy in the diagnosis of periampullary carcinoma.

In view of the limited yield of surface ampullary biopsy, different techniques have been applied in an effort to increase the yield of ampullary biopsy in the diagnosis of periampullary carcinoma.

In the present study, the authors studied the role of needle knife assisted ampullary biopsy in the diagnosis of periampullary carcinoma.

The study results suggest that needle knife assisted ampullary biopsy is a useful technique for increasing the yield of ampullary biopsy in the diagnosis of periampullary carcinoma.

This paper describes an alternative approach to obtain deep biopsy specimens from papillary tumors, substantially increasing the diagnostic accuracy, according to the data described in the paper.

Peer reviewers: John A Karagiannis, Associate Professor, Gastroenterology Unit, “Konstantopoulio” Hospital, 3-5 Agias Olgas Street, N.Ionia, Athens 14233, Greece; Tony Chiew Keong Tham, MD, Consultant Gastroenterologist, Ulster Hospital, Dundonald, Belfast BT16 1RH, Northern Ireland, United Kingdom

S- Editor Zhang SJ L- Editor Roemmele A E- Editor Zheng XM

| 1. | Oliai A, Koff RS. Disappearance and prolonged absence of jaundice and hyperbilirubinemia in carcinoma of the ampulla of Vater. Am J Gastroenterol. 1973;59:518-521. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Geer RJ, Brennan MF. Prognostic indicators for survival after resection of pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Am J Surg. 1993;165:68-72; discussion 72-3. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 548] [Cited by in RCA: 548] [Article Influence: 17.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 3. | Kimchi NA, Mindrul V, Broide E, Scapa E. The contribution of endoscopy and biopsy to the diagnosis of periampullary tumors. Endoscopy. 1998;30:538-543. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Yamaguchi K, Enjoji M, Kitamura K. Endoscopic biopsy has limited accuracy in diagnosis of ampullary tumors. Gastrointest Endosc. 1990;36:588-592. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 137] [Cited by in RCA: 119] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Leese T, Neoptolemos JP, West KP, Talbot IC, Carr-Locke DL. Tumours and pseudotumours of the region of the ampulla of Vater: an endoscopic, clinical and pathological study. Gut. 1986;27:1186-1192. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Menzel J, Poremba C, Dietl KH, Böcker W, Domschke W. Tumors of the papilla of Vater--inadequate diagnostic impact of endoscopic forceps biopsies taken prior to and following sphincterotomy. Ann Oncol. 1999;10:1227-1231. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 7. | Ponchon T, Berger F, Chavaillon A, Bory R, Lambert R. Contribution of endoscopy to diagnosis and treatment of tumors of the ampulla of Vater. Cancer. 1989;64:161-167. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Morris-Stiff G, Teli M, Jardine N, Puntis MC. CA19-9 antigen levels can distinguish between benign and malignant pancreaticobiliary disease. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2009;8:620-626. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Huibregtse K, Tytgat GN. Carcinoma of the ampulla of Vater: the endoscopic approach. Endoscopy. 1988;20 Suppl 1:223-226. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Bourgeois N, Dunham F, Verhest A, Cremer M. Endoscopic biopsies of the papilla of Vater at the time of endoscopic sphincterotomy: difficulties in interpretation. Gastrointest Endosc. 1984;30:163-166. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Seifert E, Schulte F, Stolte M. Adenoma and carcinoma of the duodenum and papilla of Vater: a clinicopathologic study. Am J Gastroenterol. 1992;87:37-42. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Shoup M, Hodul P, Aranha GV, Choe D, Olson M, Leya J, Losurdo J. Defining a role for endoscopic ultrasound in staging periampullary tumors. Am J Surg. 2000;179:453-456. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Puli SR, Singh S, Hagedorn CH, Reddy J, Olyaee M. Diagnostic accuracy of EUS for vascular invasion in pancreatic and periampullary cancers: a meta-analysis and systematic review. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;65:788-797. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |