Published online Nov 16, 2011. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v3.i11.213

Revised: September 4, 2011

Accepted: September 11, 2011

Published online: November 16, 2011

AIM: To study the endoscopic and radiological characteristics of patients with hepaticojejunostomy (HJ) and propose a practical HJ stricture classification.

METHODS: In a retrospective observational study, a balloon-assisted enteroscopy (BAE)-endoscopic retrograde cholangiography was performed 44 times in 32 patients with surgically-altered gastrointestinal (GI) anatomy. BAE-endoscopic retrograde cholangio pancreatography (ERCP) was performed 23 times in 18 patients with HJ. The HJ was carefully studied with the endoscope and using cholangiography.

RESULTS: The authors observed that the hepaticojejunostomies have characteristics that may allow these to be classified based on endoscopic and cholangiographic appearances: the HJ orifice aspect may appear as small (type A) or large (type B) and the stricture may be short (type 1), long (type 2) and type 3, intrahepatic biliary strictures not associated with anastomotic stenosis. In total, 7 patients had type A1, 4 patients A2, one patient had B1, one patient had B (large orifice without stenosis) and one patient had type B3.

CONCLUSION: This practical classification allows for an accurate initial assessment of the HJ, thus potentially allowing for adequate therapeutic planning, as the shape, length and complexity of the HJ and biliary tree choice may mandate the type of diagnostic and therapeutic accessories to be used. Of additional importance, a standardized classification may allow for better comparison of studies of patients undergoing BAE-ERCP in the setting of altered upper GI anatomy.

- Citation: Mönkemüller K, Jovanovic I. Endoscopic and retrograde cholangiographic appearance of hepaticojejunostomy strictures: A practical classification. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2011; 3(11): 213-219

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v3/i11/213.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v3.i11.213

Occasionally, patients with previous complex upper gastrointestinal (GI) surgery and hepaticojejunostomy (HJ) present with pancreatobiliary problems[1-5]. HJ is a common curative and palliative procedure performed for benign and malignant biliary obstruction. The incidence of anastomotic stricture following HJ in experienced centers is 4%-10%[1-3]. Because re-operation carries a significant morbidity, endoscopic or radiological approaches to treat these strictures are now preferred[1-3]. Nevertheless, performing an endoscopic retrograde cholangio pancreatography (ERCP) in these patients is technically very challenging or impossible, frequently mandating an operative intervention. However, the advent of balloon-assisted enteroscopy (BAE)[4] has increased our ability to reach the HJ located in the excluded limb and perform diagnostic and therapeutic endoscopic retrograde cholangiography (ERC)[3-18]. During BAE-ERC, we have observed that the HJ and biliary tree have specific appearances (i.e., patterns).

The aims of this study were to assess the endoscopic and radiological characteristics of the HJ of patients with Roux-en-Y anastomosis presenting with biliary problems undergoing BAE-ERC and propose a practical HJ stricture classification.

Over a period of 4 years, we performed 44 BAE-ERCPs in 32 patients with various types of complex post-surgical upper GI anatomy and pancreatobiliary problems. In the present study, we focused on the endoscopic and radiological findings of hepaticojejunostomies. Patients without HJ or with intact papilla were excluded. The procedures were performed at the University of Magdeburg Medical Center and Marienhospital, Bottrop, Germany. All patients provided written informed consent before the endoscopy. The study was approved by the institutional review board and conducted according to the guidelines of Helsinki.

The patients were placed in the prone position and the endoscopy was performed using conscious sedation with midazolam and propofol with constant monitoring of vital signs. ERC was performed with the therapeutic DBE (DBE-EN-450T5, Fujinon, Saitama, Japan) with a working channel of 2.8 mm diameter and a 140 cm long, 13.5 mm diameter overtube (TS Fujinon, 13.5 mm, Saitama, Japan). The ERC was performed either with balloons mounted on both the enteroscope and overtube or only on the overtube. The details of the procedure have been described in detail elsewhere[6-10]. BAE-ERC was performed under fluoroscopic control using a C-arm (Philips, Holland). Cannulation of the biliary tract was achieved with a tapered tip biliary catheter (F3CTPK1810250M, Fujinon, Japan) and two types of guidewires: Jagwire (Boston Scientific, Miami, United States) or the FTE-Wildcat nitinol exchange guide wire (650 cm long, F3LQPK0850650X-S) Fujinon Europe, GmbH). The following stents were used: 7 Fr 5 cm long (Wilson Cook, Ireland). These stents were pushed with the biliary catheter or the customized pusher tube for the DBE system (Fujinon FPU7270: this pusher pushes 7 Fr stents and has a length of 270 cm). These additional accessories were used to accomplish the various interventional procedures: balloon dilation of the anastomosis was performed using a constant radial expansion (CRE) wire-guided balloon dilatation catheter (Wire-guided 240 cm, CRE™ Balloon Dilator, Boston Scientific Medizintechnik GmbH, Ratingen, Germany).

Descriptive statistics were employed to describe the patient’s demographics and clinical characteristics, presenting means and ranges.

ERCP using the DBE was performed on 44 occasions in 32 patients (10 female and 22 male, mean age 62.5, range 25 to 78) with altered upper GI anatomy. Twenty three BAE-ERCPs were performed in 18 patients with Roux-en-Y type of reconstruction with HJ and represent the study group. In fourteen patients (3 female, and 11 male), the HJ could be clearly visualized and cannulated. In five patients, multiple procedures (2 to 3) were performed (e.g., follow-up to remove or place new stents). Thus, a total of 19 out of 23 (82%) procedures were successful (Table 1). The mean follow-up has been 18 mo (range 6 to 40 mo). Table 1 summarizes the demographic, clinical, endoscopic findings, procedures and interventions of the study group. Indications for ERC included biliary obstruction and cholestasis in all patients. The procedure lasted a mean time of 70 min (range 35 to 240 min).

| No | Sex | Age (yr) | Indication | Post surgical anatomy | Findings | Intervention |

| 1 | Male | 55 | Jaundice | s/p Whipple with Roux-en-Y HJ | A1 | Stenting |

| Stent extraction and new stent (× 2) | ||||||

| Balloon dilation | ||||||

| 2 | Male | 55 | Cholestasis, jaundice | s/p Whipple with Roux-en-Y HJ | A1 | Cannulation with Jagwire |

| Cholangiogram | ||||||

| Stenting | ||||||

| 3 | Female | 78 | Upper GI-bleeding, melena, suspicious bleeding from the afferent loop | s/p Roux-en-Y HJ after complicated CCE | B | Direct endoscopic cholangiogram |

| APC-therapy of angiodysplasias at the HJ | ||||||

| 4 | Male | 36 | Cholestasis, recurrent cholangitis | s/p Whipple with Roux-en-Y HJ | A2 | Cholangiogram |

| Stent placement | ||||||

| Stone extraction | ||||||

| 5 | Male | 69 | Jaundice, suspicious relapse of Klatskin-Tumor | s/p partial CBD resection with hepaticojejunostomy | NA | Tumor biopsies at the HJ |

| Cannulation failed | ||||||

| => PTCD | ||||||

| 6 | Male | 70 | Cholestasis | s/p Whipple’s operation, Roux-en-Y HJ | A1 | Cholangiogram |

| Stent insertion | ||||||

| 7 | Male | 77 | Cholestasis | s/p partial gastric resection with Roux-en-Y HJ | A2 | Cannulation with Jagwire |

| Cholangiogram | ||||||

| s/p PTCD | DHC-stenosis | |||||

| No stent | ||||||

| 8 | Male | 72 | Cholangitis | s/p Roux-en-Y HJ | NA | Failed (adhesions) |

| 9 | F | 36 | Cholestasis, chronic abdominal pain | s/p Roux-en-Y HJ | A1 | Cholangiogram |

| Balloon dilatation | ||||||

| Perforation | ||||||

| 10 | Male | 36 | Cholestasis | s/p at age of 17 with Roux-en-Y HJ | B3 | Referred for OLT |

| Late onset ulcerative colitis | ||||||

| 11 | Male | 65 | Choledocolithiasis, abdominal pain, cholestasis | s/p Whipple’s operation, Roux-en-Y HJ | A1 | Balloon dilation and stenting |

| Stent and stone extraction | ||||||

| 12 | Female | 25 | Cholangitis | s/p at age of 3 resection of a choledococele with Roux-en-Y HJ | A1 | Bougienage of CBD stenosis and stent (× 2) insertion |

| Stent retrieval and balloon dilation of CBD stenosis | ||||||

| 13 | Female | 75 | Choledocolithiasis | s/p Roux-en-Y HJ after complicated CCE (iatrogenic bile duct injury) | NA | Failed, adhesions, afferent limb intubated but proximal end not reached and HJ not found |

| 14 | Male | 70 | Cholestasis | s/p Whipple’s operation, Roux-en-Y HJ | B1 | Failed, oxygen desaturation |

| Cholangiogram, biliary stent insertion | ||||||

| 15 | Male | 72 | Cholangitis | s/p Roux-en-Y with HJ after a complicated CCE (gangrenous cholecystitis) | A2 | Dilation of CBD stenosis |

| Biliary stent insertion | ||||||

| 16 | Male | 54 | Choledocolithiasis | s/p partial gastric resection with Roux-en-Y HJ | A2 | Dilation of CBD stenosis, stent insertion |

| Stone extraction | ||||||

| 17 | Female | 58 | Choledocolithiasis | s/p Whipple’s operation, Roux-en Y HJ | NA | Failed, adhesions, afferent limb intubated but proximal end not reached and HJ not found |

| 18 | Male | Jaundice | s/p Whipple’s operation, Roux-en Y HJ | A1 | Dilatation | |

| Stenting |

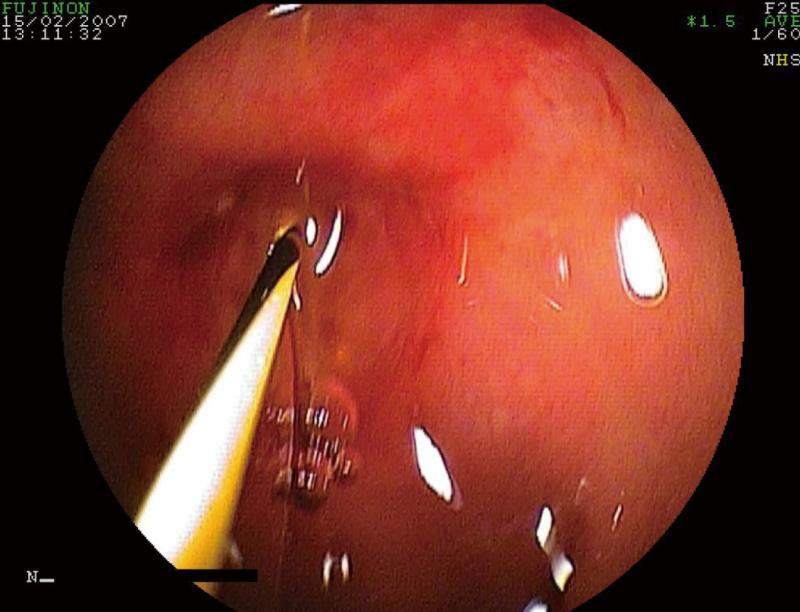

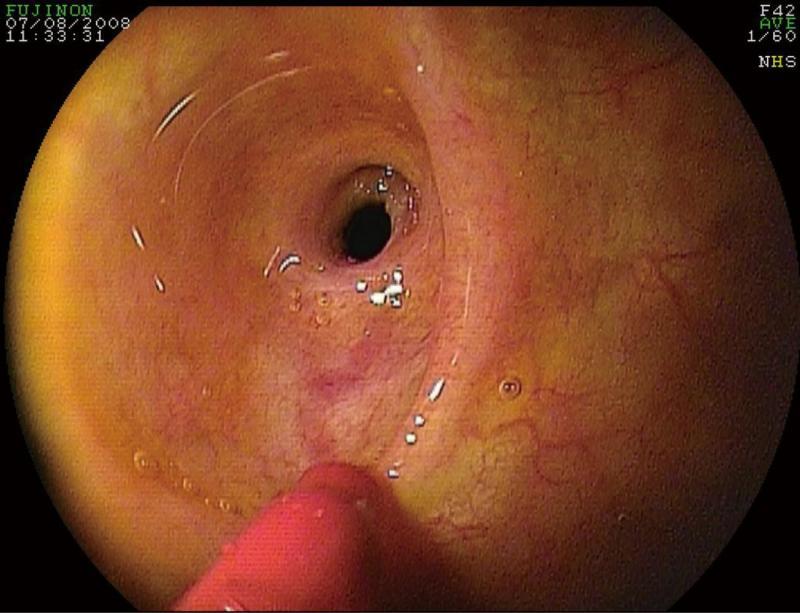

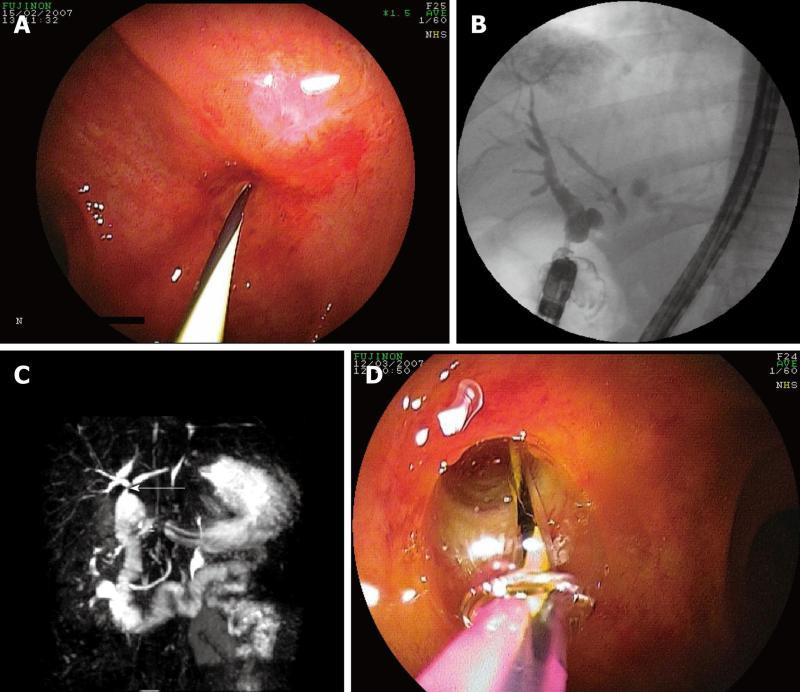

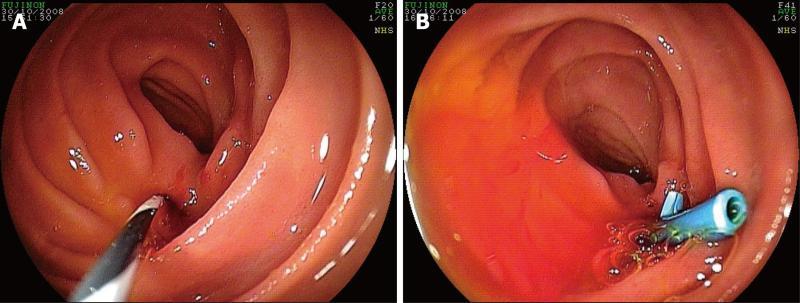

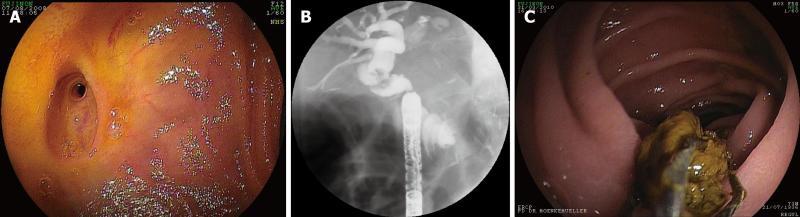

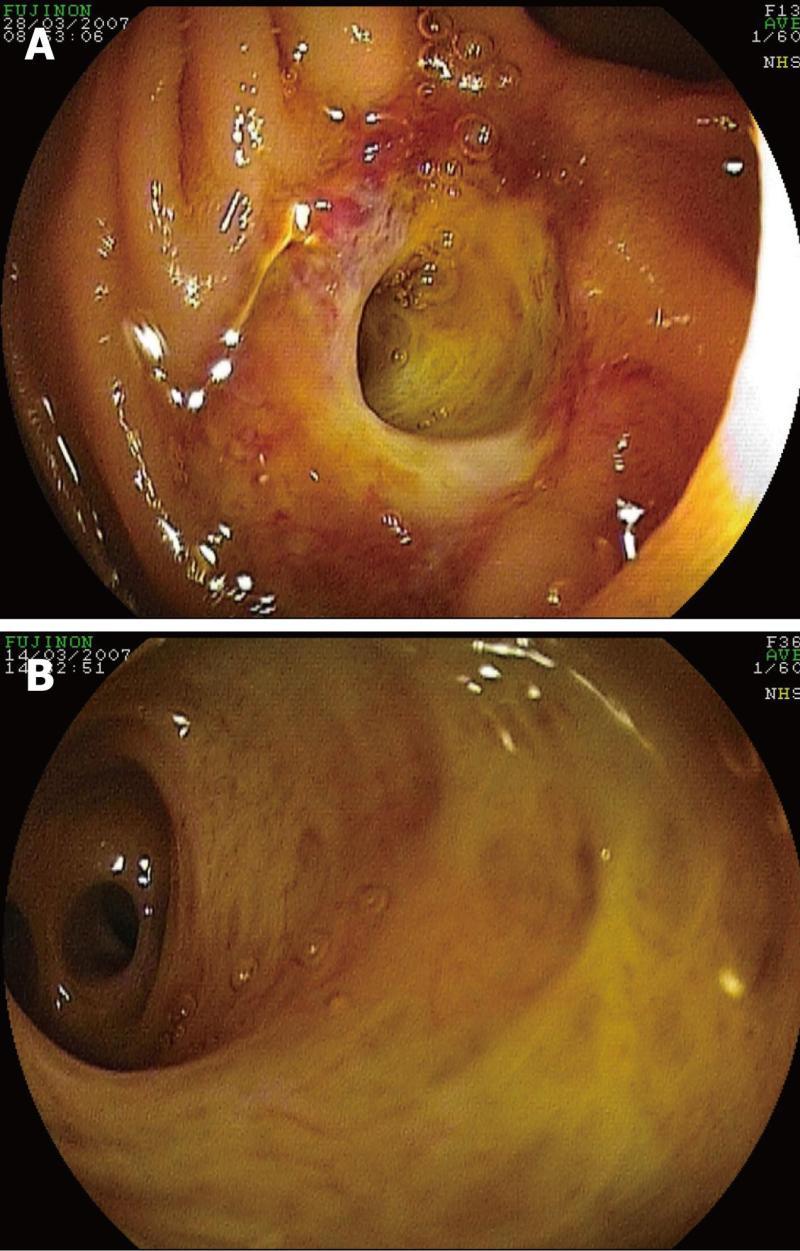

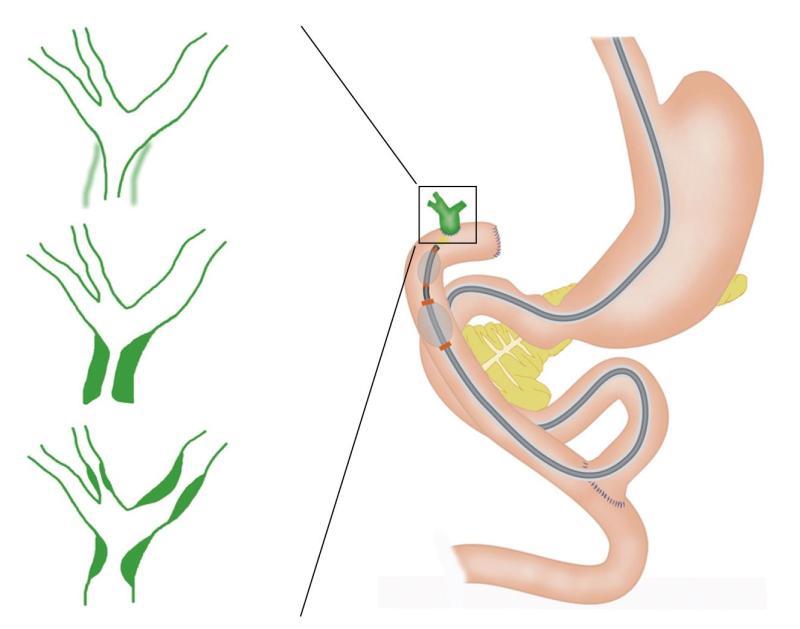

We observed that the HJ does not have a uniform appearance but rather a few key characteristics that may allow the stenosis to be stratified based on endoscopic (letter classification, i.e., A, B, C and D) and cholangiographic appearance (numbers, i.e. 0, 1, 2 and 3) (Table 2). Endoscopically, the HJ orifice can appear as small (type A) (Figure 1), large (type B) (Figure 2), normal (C) and double (i.e., separate anastomosis for the left and right hepatic ducts) (D)[17]. Of note, the endoscopic appearance allows classification of the HJ-orifice at the level of the lumen or above it. In Figure 2, a case of a suprastenotic stricture is seen, i.e. the anastomosis at the luminal level is wide open or normal, whereas there is a clear stricture a few millimeters above it (i.e., proximal) (Figure 2). This is a supra-anastomotic stricture (S) (Table 2).

| Type | Endoscopic findings |

| A | Small opening |

| B | Large opening |

| C | Normal opening |

| D | Double opening (i.e., double anastomosis) |

| S | Supra-anastomotic stricture1 |

| Cholangiographic findings | |

| 0 | No stricture |

| 1 | Short stricture |

| 2 | Long stricture |

| 3 | Intrahepatic strictures |

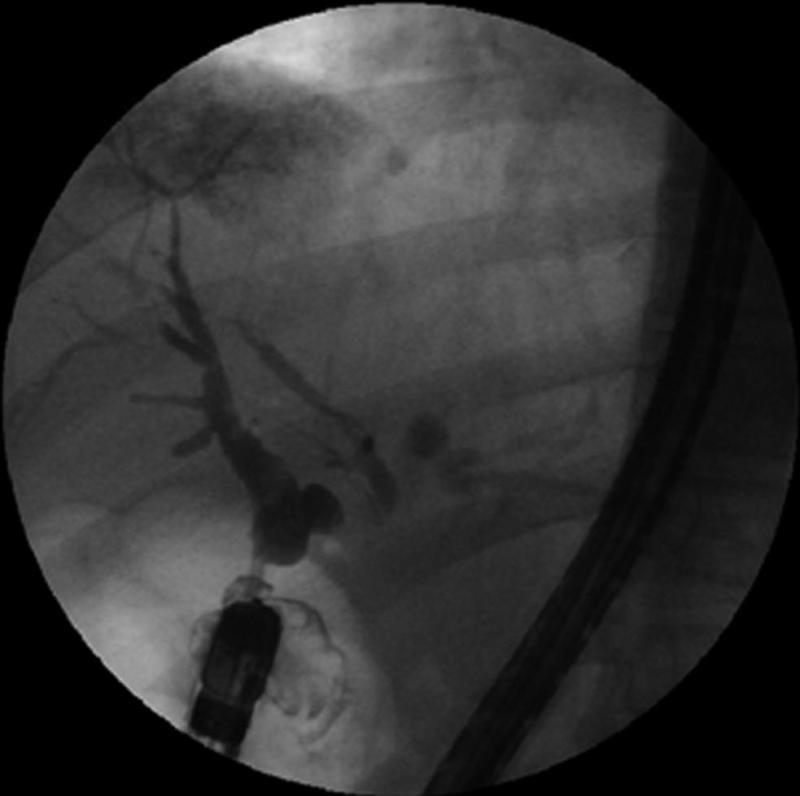

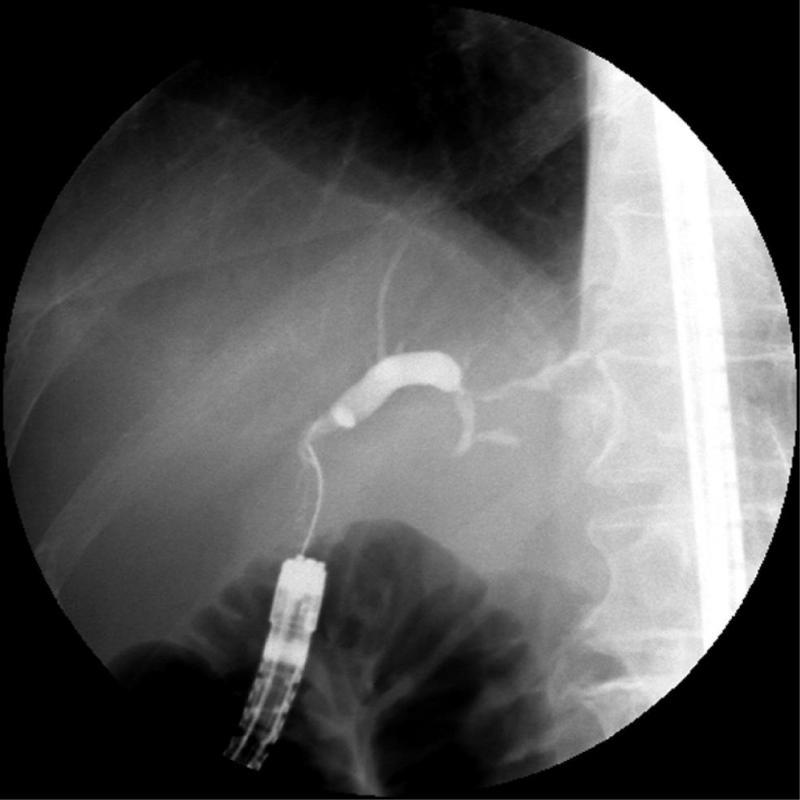

After the cholangiogram was performed, the biliary tract was depicted and a stricture was verified, which was short (type 1) (Figure 3), long (type 2) (Figure 4) and type 3, intrahepatic biliary strictures not associated with anastomosis, i.e., non-anastomotic, e.g., sclerosing cholangitis) (Figure 5). In the theoretical case of absence of cholangigraphic stricture, the classification would be type 0. In total, 7 patients had type A1 (Figure 6A-D), 4 patients A2 (Figure 7A and B), one patient had B1 (Figure 8A-C), one patient had B3 and one patient had large orifice HJ without stenosis (type B0, Figure 9A and B). The types of HJ found in each patient are depicted in Table 1. Interestingly, when observing a large opening of the HJ, a stenosis cannot be completely excluded as this can be located in the supra-anastomotic segment of the bile duct (type B, Figure 8A). In these cases, the stricture may be either short (type 1) or long (type 2). In other cases of type B or D HJ orifice (wide opening), a direct cholangiography using the thin enteroscope can be accomplished (Figures 9A and B). In occasional cases, unexpectedly, strictures may not be directly related to the HJ operation at all and affect the biliary tract diffusely, such as in a case of primary sclerosing cholangitis (type 3, Figure 5). The proposed classification and various types of HJ strictures are depicted in Figure 10. In addition, the proposed classification is summarized in Table 2.

In three patients, we were unable to deeply intubate the afferent limb. In another patient, the HJ was infiltrated with a recurrent Klatskin tumor impeding cannulation of the bile duct (Patient No. 5). The overall diagnostic success was 93% (13/14) and the endoscopic therapeutic success was 75% (9/13, in one patient no therapeutic intervention was attempted as he had sclerosing cholangitis and was referred for liver transplantation). Therapeutic interventions included biliary stent insertion (n = 8), dilation of common bile duct stenosis with a balloon (n = 5), stone removal with Dormia basket (n = 3) and stent retrieval (n = 5) (therapeutic interventions exceeds the number of patients as in some patients more than one procedure was done). One complication occurred. This was a perforation of a HJ during balloon dilation (Table 1, Case No. 9). The patient was taken to the operating room immediately and a new surgical HJ was performed after extracting multiple stones from the biliary tract.

We and others have demonstrated that diagnostic and therapeutic ERCP with the BAE in patients with altered bowel anatomy is feasible, allowing for the localization of the afferent limb, visualization of the HJ or papilla of Vater and demonstration of anastomotic strictures or bile duct stones of the choledochojejunostomy[5-17,19]. Besides diagnostic capabilities, BAE-ERCP also permits therapeutic interventions such as sphincterotomy, biliary stent placement, biliary balloon dilation and stent extraction[5-18]. Anastomotic strictures account for the majority of secondary long-term complications of hepaticojejunostomies such as hepaticolithiasis (stones in the hepatic duct), liver abscess and secondary biliary cirrhosis if left untreated[2,3]. Almost 50% of the strictures develop within the first 5 years after surgery whereas the remaining occur at later intervals[2,3]. Recurrences requiring further treatment occur in about 20%-25% of cases[2,3,20,21].

During BAE-ERC we observed that the HJ and biliary tree have specific appearances that may allow it to be classified based on endoscopic and cholangiographic appearances. In almost half of our cases, the opening of the HJ was very small, barely permitting the passage of a 0.035 inch wire or a tapered 5 Fr catheter (type A), suggestive of a stenosis at the level of anastomosis. However, the cholangiographic appearance was vital in determining the length of the stricture, as in some cases the stricture was short and in others long. Short strictures are classified as type 1 and long strictures as type 2. Thus, a small HJ orifice (type A) with a short stricture (type 1) is classified as A1. The therapeutic approach to this type of stricture may be different from one that has a wide HJ orifice (type B). From our own experience, in cases of type A1 HJ stricture, it is advisable to place a stent into the bile duct in order to enlarge and “soften” the small HJ and, in a second session, proceed with balloon dilation of the HJ stricture, a lesson we learned from our case of balloon-induced perforation (Patient No. 9, Table 1). In the same vein, long strictures may fare better with bougienage and/or previous stenting and subsequent balloon dilation. However, our study was not designed to evaluate whether this classification has implications in therapeutic outcomes. We mainly wanted to describe the types of hepaticojejunostomies that can be found and propose a potential classification or basis for future standardized classifications. Whether our classification will have wide applicability is unknown at present. However, we strongly believe that describing the different appearances of the HJ has practical consequences. We also believe that this classification may lead to a better understanding of the post-surgical changes of the HJ and a better appreciation of the diagnostic and therapeutic success of endoscopic interventions. Therefore, other endoscopists interested in treating patients with biliopancreatic disorders after major surgical interventions with altered upper GI anatomy may apply the presented information. We truly expect that our results should be reproducible. Indeed, upon reviewing the reported literature, we find that the reported endoscopic and cholangiographic pictures could fall into the classification presented herein.

A potential limitation of the study is its retrospective design. Nevertheless, the immense collection of endoscopic and cholangiographic images, coupled with the careful, prospective collected database of our centers, has allowed us to make these careful observations. Indeed, our series has the advantage of providing an extensive and detailed endoscopic and cholangiographic description of the HJ.

In summary, this endoscopic-radiological description and the proposed classification is practical as it provides a quick and accurate initial endoscopic assessment of the HJ, potentially allowing for adequate therapeutic planning, as the shape, length and complexity of the HJ and biliary tree may mandate the type of diagnostic and therapeutic accessories to be used to treat the stricture (e.g., balloon vs bougie dilatation, Soehendra screw-type stent extractor or 3.3F peripheral angioplasty balloon over a 0.018 inch guidewire). Furthermore, such a practical classification method to characterize the HJ stenosis may be reproducible and thus allow better comparison of the diagnostic and therapeutic results of BAE-ERC in patients with Roux-en-Y anastomosis and HJ.

Ivan Jovanovic, MD, PhD is a recipient of the ASGE Cook Don Wilson Award 2010. This work was performed during his award period with Prof. Klaus Mönkemüller at the Marienhospital Bottrop, Germany.

Performing an endoscopic retrograde cholangio pancreatography (ERCP) in patients with Roux-en-Y and hepaticojejunostomy (HJ) anastomosis is technically very challenging or impossible, frequently mandating an operative intervention. The advent of balloon-assisted enteroscopy (BAE) has increased the authors’ ability to reach the HJ and perform ERCP.

Although there are various types of hepaticojejunostomies, there have been no focused attempts to categorize these endoscopically. In this study, the authors describe the endoscopic and radiological characteristics of the hepaticojejunal anastomosis of patients with HJ and propose a practical HJ stricture classification.

The authors observed that the hepaticojejunostomies have characteristics that may allow the stenosis to be classified based on endoscopic and cholangiographic appearances: the HJ orifice aspect may appear small (type A) or large (type B), normal (C), double (i.e. separate anastomosis for the left and right hepatic ducts) (D). The stricture may be short (type 1), long (type 2) and type 3, intrahepatic biliary strictures not associated with anastomotic stenosis. In addition, the anastomosis may not be strictured (0) or the stricture may be above the anastomosis, i.e. supra-anstomotic stricture (S).

By understanding the anatomy of hepaticojejunostomies, this classification potentially allows for adequate therapeutic planning, as the shape, length and complexity of the HJ and biliary tree choice may dictate the type of diagnostic and therapeutic accessories to be used.

A standardized classification may allow for better understanding and comparison of studies of patients undergoing BAE-ERCP in the setting of altered upper gastrointestinal anatomy.

The authors present a combined endoscopic and radiological classification of HJ as visualized by balloon-assisted endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. While the clinical implications of such a scoring system are not known nor validated in other reports, it does provide a framework for other investigators to use, modify or refute.

Peer reviewers: C Mel Wilcox, MD, Professor, Director, UAB Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, 703 19th Street South, ZRB 633, Birmingham, AL 35294-0007, United States; Tom G Moreels, MD, PhD, Professor, Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Antwerp University Hospital, Wilrijkstraat 10, B-2650 Antwerp, Belgium

S- Editor Zhang SJ L- Editor Roemmele A E- Editor Zheng XM

| 1. | Way LW, Bernhoft RA, Thomas MJ. Biliary stricture. Surg Clin North Am. 1981;61:963-972. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Tocchi A, Costa G, Lepre L, Liotta G, Mazzoni G, Sita A. The long-term outcome of hepaticojejunostomy in the treatment of benign bile duct strictures. Ann Surg. 1996;224:162-167. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Röthlin MA, Löpfe M, Schlumpf R, Largiadèr F. Long-term results of hepaticojejunostomy for benign lesions of the bile ducts. Am J Surg. 1998;175:22-26. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Mönkemüller K, Fry LC, Bellutti M, Malfertheiner P. Balloon-assisted enteroscopy: unifying double-balloon and single-balloon enteroscopy. Endoscopy. 2008;40:537; author reply 539. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Aabakken L, Bretthauer M, Line PD. Double-balloon enteroscopy for endoscopic retrograde cholangiography in patients with a Roux-en-Y anastomosis. Endoscopy. 2007;39:1068-1071. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 158] [Cited by in RCA: 151] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Kuga R, Furuya CK, Hondo FY, Ide E, Ishioka S, Sakai P. ERCP using double-balloon enteroscopy in patients with Roux-en-Y anatomy. Dig Dis. 2008;26:330-335. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Mönkemüller K, Fry LC, Bellutti M, Neumann H, Malfertheiner P. ERCP with the double balloon enteroscope in patients with Roux-en-Y anastomosis. Surg Endosc. 2009;23:1961-1967. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Maaser C, Lenze F, Bokemeyer M, Ullerich H, Domagk D, Bruewer M, Luegering A, Domschke W, Kucharzik T. Double balloon enteroscopy: a useful tool for diagnostic and therapeutic procedures in the pancreaticobiliary system. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:894-900. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Neumann H, Fry LC, Meyer F, Malfertheiner P, Monkemuller K. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography using the single balloon enteroscope technique in patients with Roux-en-Y anastomosis. Digestion. 2009;80:52-57. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Koornstra JJ. Double balloon enteroscopy for endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreaticography after Roux-en-Y reconstruction: case series and review of the literature. Neth J Med. 2008;66:275-279. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Saleem A, Baron TH, Gostout CJ, Topazian MD, Levy MJ, Petersen BT, Wong Kee Song LM. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography using a single-balloon enteroscope in patients with altered Roux-en-Y anatomy. Endoscopy. 2010;42:656-660. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Emmett DS, Mallat DB. Double-balloon ERCP in patients who have undergone Roux-en-Y surgery: a case series. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;66:1038-1041. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Koornstra JJ, Fry L, Mönkemüller K. ERCP with the balloon-assisted enteroscopy technique: a systematic review. Dig Dis. 2008;26:324-329. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Dellon ES, Kohn GP, Morgan DR, Grimm IS. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography with single-balloon enteroscopy is feasible in patients with a prior Roux-en-Y anastomosis. Dig Dis Sci. 2009;54:1798-1803. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Moreels TG, Pelckmans PA. Comparison between double-balloon and single-balloon enteroscopy in therapeutic ERC after Roux-en-Y entero-enteric anastomosis. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;2:314-317. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Lopes TL, Wilcox CM. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography in patients with Roux-en-Y anatomy. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2010;39:99-107. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Moreels TG, Hubens GJ, Ysebaert DK, Op de Beeck B, Pelckmans PA. Diagnostic and therapeutic double-balloon enteroscopy after small bowel Roux-en-Y reconstructive surgery. Digestion. 2009;80:141-147. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Mönkemüller K, Wilcox CM, Muñoz-Navas M. Interventional and Therapeutic Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. Basel: Karger AG Publishing 2010; 430-431. |

| 19. | Mönkemüller K, Bellutti M, Neumann H, Malfertheiner P. Therapeutic ERCP with the double-balloon enteroscope in patients with Roux-en-Y anastomosis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;67:992-996. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Davids PH, Tanka AK, Rauws EA, van Gulik TM, van Leeuwen DJ, de Wit LT, Verbeek PC, Huibregtse K, van der Heyde MN, Tytgat GN. Benign biliary strictures. Surgery or endoscopy? Ann Surg. 1993;217:237-243. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Csendes A, Navarrete C, Burdiles P, Yarmuch J. Treatment of common bile duct injuries during laparoscopic cholecystectomy: endoscopic and surgical management. World J Surg. 2001;25:1346-1351. [PubMed] |