Published online Jan 16, 2011. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v3.i1.16

Revised: December 13, 2010

Accepted: December 20, 2010

Published online: January 16, 2011

Gastric outlet obstruction is commonly associated with malignancies and peptic ulcer disease. However, when no malignancy is seen and the patient is non-responsive to conventional peptic ulcer treatment, other etiologies need to be explored. We report a case of gastric outlet obstruction due to duodenal tuberculosis. The patient is a 31 year old male who presented with 1 year history of recurrent epigastric pain and an acute episode of vomiting. Endoscopy revealed duodenal stricture. Computed tomography scan showed pyloroantral thickening. The patient was referred to the surgery service and underwent an exploratory laparotomy and gastrojejunostomy. A duodenal mass and calcified lymph nodes were noted on exploration and biopsy revealed a tuberculous origin. The patient was started on anti-tuberculosis medications and had improved on discharge. Gastroduodenal tuberculosis is rare and pyloric stenosis resulting from tuberculosis is even rarer. This, however, should be considered in patients who come from areas where the disease is endemic.

- Citation: Flores HB, Zano F, Ang EL, Estanislao N. Duodenal tuberculosis presenting as gastric outlet obstruction: A case report. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2011; 3(1): 16-19

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v3/i1/16.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v3.i1.16

Tuberculosis is a major health problem worldwide. In the Philippines, it is endemic. The most common manifestation is a pulmonary disease but involvement of the gastrointestinal tract is not uncommon. Gastrointestinal tuberculosis often involves the ileocecal region. The stomach as well as the duodenum are rare sites for tuberculosis and are usually a result of secondary spread from a primary pulmonary disease. An autopsy series reported an incidence of only 0.5%[1]. A primary case of gastroduodenal tuberculosis is an even rarer disease and only a few cases are reported in the literature[1-5].

A 31 year old male was admitted to our institution with a 1 year history of recurrent epigastric pain and an acute episode of vomiting. Epigastric pain was characterized as intermittent, mild and gnawing in character. The patient also reported a slight undocumented weight loss. No other associated signs and symptoms were noted. No medications had been taken and he had not consulted medical staff. The patient had an acute episode of vomiting, prompting a consultation and subsequent admission. The patient had no known co-morbidities and no history of hospitalization. He had no history of tuberculosis and no known exposure to the disease. The patient’s family history was also unremarkable.

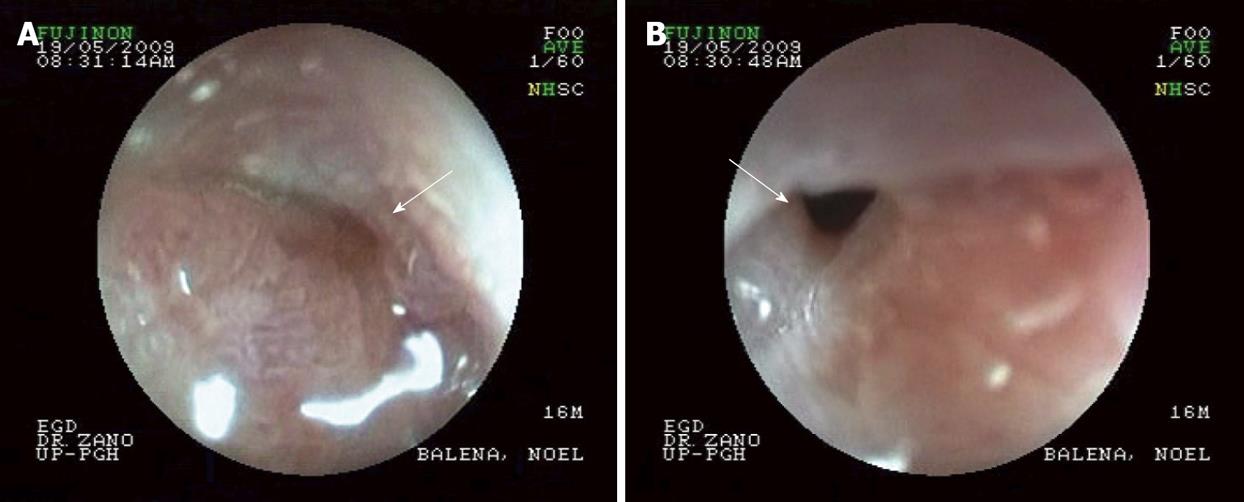

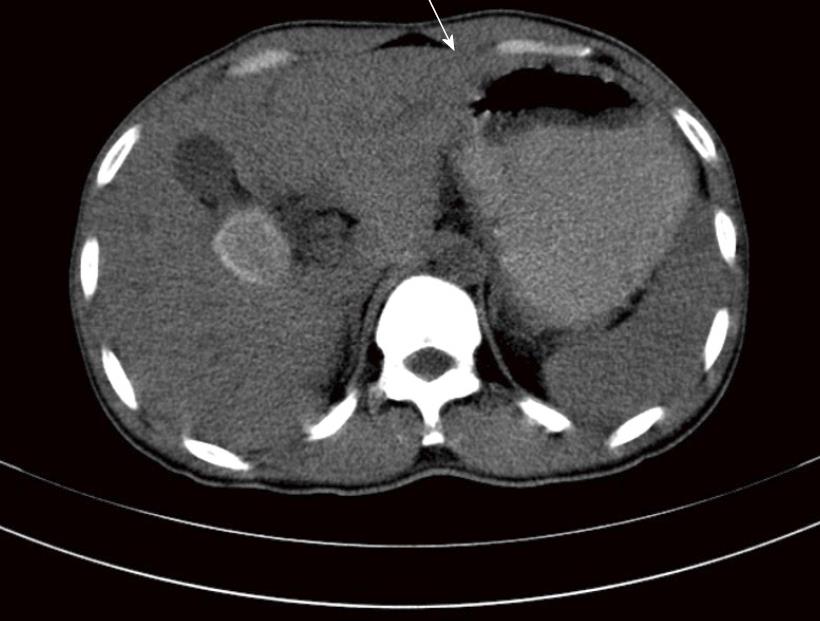

Physical examination only revealed direct tenderness in the epigastrium. There was no note of lymphadenopathies and the rest of the physical exam was unremarkable. Body mass index was 21. Complete blood count was within normal limits. Chest x-ray was normal. Esophagogastroduodenoscopy revealed duodenal stricture at the 1st part of the duodenum (Figure 1). Computed tomography of the whole abdomen showed pyloroantral thickening and a distended stomach (Figure 2). The impression then was gastric outlet obstruction secondary to duodenal stricture, probably secondary to peptic ulcer cicatrization to rule out duodenal malignancy.

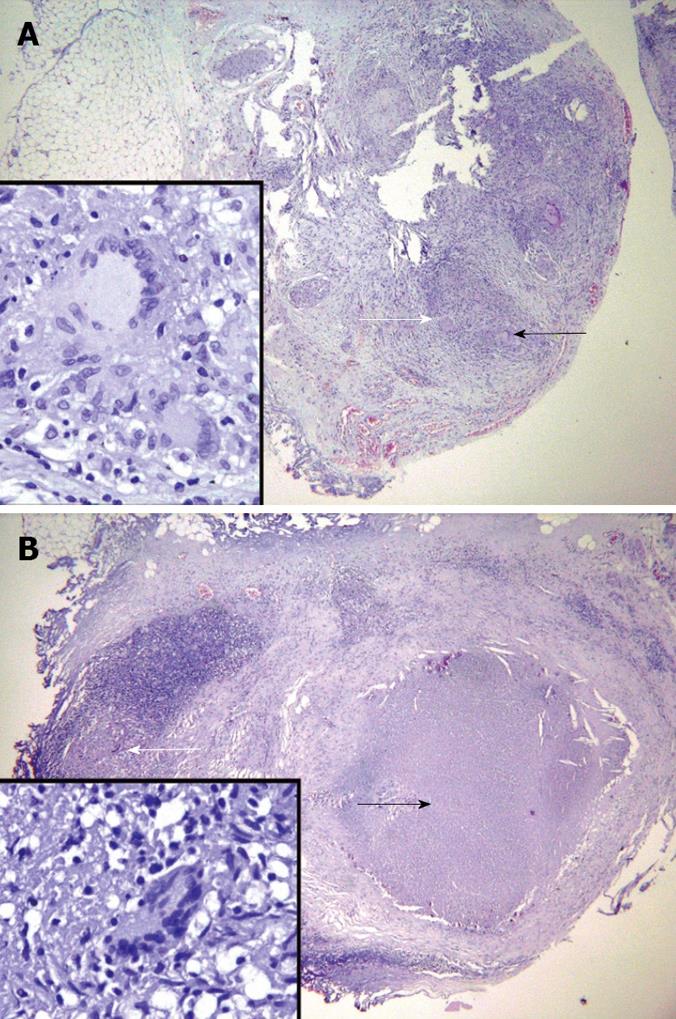

The patient was referred to the surgical service. He underwent exploratory laparotomy and gastrojejunostomy. A duodenal mass and calcified lymph nodes were noted intraoperatively. Excision of the mass was done as well as biopsy of the calcified lymph nodes. Post-operative recovery was uneventful. On histopathological examination, a chronic granulomatous inflammation with Langhans-type giant cell in the duodenal wall and the calcified lymph node showed caseation necrosis and multi-loculated giant cells were noted (Figure 3A and B). The patient was then diagnosed as having duodenal stricture secondary to primary duodenal tuberculosis.

The patient was started on quadruple anti-tuberculous medication and had improved on discharge. The patient was symptom free 3 mo later.

Gastric outlet obstruction is commonly associated with malignancies and peptic ulcer disease. However, when no malignancy is seen and a patient is non-responsive to conventional peptic ulcer treatment, other etiologies need to be explored. In this case, our patient presented with gastric outlet obstruction and a diagnosis of ulcer cicatrization was first made since it is one of the more common causes of duodenal strictures. Also, his young age made the diagnosis of malignancy less likely. Since the patient already presented with gastric outlet obstruction, surgery was deemed necessary for the patient and the diagnosis of gastroduodenal tuberculosis was made post-operatively. In other reported cases of gastroduodenal tuberculosis, medical management was a sufficient treatment modality[2]. However, for those presenting with obstruction, surgery may be necessary to relieve the obstruction and make the diagnosis.

The diagnosis of this disease is difficult and is often made post-operatively. There are no pathognomonic clinical features. A review of 23 consecutive cases of gastroduodenal tuberculosis (15 year span) in India noted that vomiting (60.8%) and epigastric pain (56.5%) are the most common presenting symptoms. Other symptoms noted are weight loss, upper GI bleeding and fever. The mean age at presentation in this series was 34.4 years with the duration of symptoms varying from 2 d to 15 years[1]. Most reported cases of duodenal tuberculosis come from areas with high prevalence of tuberculosis such as India and Africa. Hence, a high index of suspicion is needed when a patient is from a place endemic for tuberculosis. Another emerging concern is the increasing prevalence of Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) infection. The annual risk of developing active tuberculosis when co-infected with HIV is 20-30 times the risk in non-HIV infected individual[6]. In the Philippines there is a low prevalence of HIV infection[7]. Thus, the HIV test was not done for this case since the patient had no high risk behavior. However, for those patients with risk factors (e.g. multiple sexual partners, men who have sex with men, intravenous drug users) and those from areas with high prevalence of HIV infection, testing for HIV co-infection may be beneficial. However, there is a lack of data on changes in the frequency or clinical manifestations of abdominal tuberculosis[6].

The radiological features of duodenal tuberculosis are also non-specific. On barium studies, patients were found to have either one or a combination of mucosal ulcerations, luminal narrowing, extrinsic compression and proximal dilatations[2]. Endoscopy may not be diagnostic and biopsies may only show nonspecific inflammation[8]. In our case, biopsy was not performed during endoscopy since the patient was already deemed to require surgery due to the obstruction. Most case reports also diagnosed duodenal tuberculosis post-operatively. Diagnosis is made through histopathological findings of caseation necrosis and Langhans type giant cell.

Management of duodenal tuberculosis is still primarily medical. Studies have shown that if the diagnosis is made prior to surgery, most lesions improve with appropriate treatment[9]. Even in patients with strictures, balloon dilatation has been shown to work together with medication[10]. In this case, no trial of medication was done since biopsy was not performed pre-operatively. Performing biopsy pre-operatively may have changed the management if the biopsy proved to be diagnostic. Also, performing a tuberculosis polymerase chain reaction test may have helped in the diagnosis if tuberculosis was made as part of the differentials. However, the cost-effectiveness of this study may need to be assessed.

In conclusion, gastroduodenal tuberculosis is rare and pyloric stenosis resulting from tuberculosis is even rarer. There are no specific signs or symptoms and no characteristic endoscopic findings. It is our recommendation that among patients with a similar presentation who come from areas endemic for tuberculosis, every effort should be made to confirm the diagnosis to avoid unnecessary surgeries.

Peer reviewers: Noriya Uedo, Director, Endoscopic Training and Learning Center; Vice Director, Department of Gastrointestinal Oncology, Osaka Medical Center for Cancer and Cardiovascular Diseases, Osaka, Japan; David Friedel, MD, Gastroenterology, Winthrop University Hospital, 222 Station Plaza North, Suite 428, Mineola NY 11501, United States

S- Editor Zhang HN L- Editor Roemmele A E- Editor Liu N

| 1. | Rao YG, Pande GK, Sahni P, Chattopadhyay TK. Gastroduodenal tuberculosis management guidelines, based on a large experience and a review of the literature. Can J Surg. 2004;47:364-368. |

| 2. | Chavhan GE, Ramakantan R. Duodenal tuberculosis: radiological features on barium studies and their clinical correlation in 28 cases. J Postgrad Med. 2003;49:214-217. |

| 3. | Gheorghe L, Băncilă I, Gheorghe C, Herlea V, Vasilescu C, Aposteanu G. Antro-duodenal tuberculosis causing gastric outlet obstruction--a rare presentation of a protean disease. Rom J Gastroenterol. 2002;11:149-152. |

| 4. | Baqai MT. Duodenal Tuberculosis: delays and difficulties in diagnosis. 2005;330-331 Available from: http://www.rcpe.ac.uk/journal/issue/journal_35_4/baqai.pdf. |

| 5. | Agrawal S, Shetty SV, Bakshi G. Primary hypertrophic tuberculosis of the pyloroduodenal area: report of 2 cases. J Postgrad Med. 1999;45:10. |

| 6. | Sinkala E, Gray S, Zulu I, Mudenda V, Zimba L, Vermund S, Drobniewski F, Kelly P. Clinical and ultrasonographic features of abdominal tuberculosis in HIV positive adults in Zambia. BMC Infectious Diseases. 2009;9:44. |

| 7. | Available from: http://www.doh.gov.ph/files/NEC_HIV_Dec-AIDSreg2008.pdf. |

| 8. | Agashe P, Dixit T. Duodenal tuberculosis a case report and review of literature. Available from: http://www.bhj.org/journal/special_issue_tb/SP_4.HTM. |

| 9. | Anand BS, Nanda R, Sachdev GK. Response of tuberculous stricture to antituberculous treatment. Gut. 1988;29:62-69. |

| 10. | Vij JC, Ramesh GN, Choudhary V, Malhotra V. Endoscopic balloon dilation of tuberculous duodenal strictures. Gastrointest Endosc. 1992;38:510-511. |

| 11. | Lamberty G, Pappalardo E, Dresse D, Denoël A. Primary duodenal tuberculosis: a case report. Acta Chir Belg. 2008;108:590-591. |

| 12. | Sandeep N, Prachis A, Saket K, Harsh U. Abdominal tuberculosis; Presentation, diagnosis and management. Hungarian Med J. 2008;2:201-214. |

| 13. | Khan R, Abid S, Jafri W, Abbas Z, Hameed K, Ahmad Z. Diagnostic dilemma of abdominal tuberculosis in non-HIV patients: an ongoing challenge for physicians. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:6371-6375. |

| 14. | Manzelli A, Stolfi VM, Spina C, Rossi P, Federico F, Canale S, Gaspari AL. Surgical treatment of gastric outlet obstruction due to gastroduodenal tuberculosis. J Infect Chemother. 2008;14:371-373. |

| 15. | Kshirsagar AY, Kanetkar SR, Langade YB, Potwar SS, Shekhar N. Duodenal stenosis secondary to tuberculosis. Int Surg. 2008;93:265-267. |

| 16. | Tan KK, Chen K, Sim R. The spectrum of abdominal tuberculosis in a developed country: a single institution’s experience over 7 years. J Gastrointest Surg. 2009;13:142-147. |