INTRODUCTION

Clostridium difficile (C. difficile) is a gram positive, anaerobic, spore forming bacterium spread by the fecal oral route[1-4]. It produces toxins A and B, causing severe mucosal destruction and pseudomembrane formation[1-5]. Clindamycin, cephalosporins and fluoroquinolones are the most common antibiotics associated with C. difficile infection[3,6,7]. The prevalence of C. difficile colitis has been increasing[8]. The percentage of complicated cases of C. difficile rose from 7.1% in 1991 to 18.2% in 2003, and the proportion of patients who died within 30 d after a severe C. difficile associated diarrheal episode rose from 4.7% in 1991 to 13.8% in 2003[9]. Between 2003 and 2006, C. difficile infection became more severe and refractory to standard therapy. It also became more likely to relapse than in previous years[4,6,10].

Toxic megacolon, first described by Marshak et al [11] in 1950 is a known complication of C. difficile colitis. The incidence of toxic megacolon associated C. difficile colitis varies from 0.4%-3% of cases[12,13]. Toxic megacolon is thought to develop from inflammatory changes that penetrate into the muscularis propria resulting in neural injury, altered motility and dilation[13]. Risk factors for toxic megacolon include any severe inflammatory condition such as inflammatory bowel disease, ischemic colitis and infectious colitis. Risk factors for development of toxic megacolon include concurrent malignancy, severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, organ transplantation, cardiothoracic procedures, diabetes mellitus, immunosuppression and renal failure[13-16]. Patients with toxic megacolon will often present with peritoneal signs, abdominal distension, diarrhea, oliguria, tachypnea, fever, hypotension, and marked leukocytosis. In atypical cases, diarrhea maybe absent[13,15,17-19].

The mortality rate of toxic megacolon secondary to C. difficile colitis is substantial and varies from 38% to 80%[5,13]. Early recognition and aggressive treatment of toxic megacolon associated with C. difficile may lead to improved outcomes. Yet, standards for diagnosis and management of this potentially lethal condition are not clearly defined.

CASE REPORT

A 64-year-old woman presented to the hospital with 3 days of abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting and profuse watery diarrhea. She was recently discharged from the hospital for a urinary tract infection and acute renal failure. She had just completed a 14 d course of ciprofloxacin.

The past medical history was significant for hyperlipidemia, hypertension, and gouty arthritis. There were no prior surgeries except for a remote history of tonsillectomy. She used tobacco and on average she drank four cans of beer daily. She denied using intravenous drugs.

On admission to the hospital the blood pressure was 65/41 mmHg. Hypothermia was present. The temperature was 35.8°C. She was obese and appeared in mild distress. Her abdomen was mildly distended, with hypoactive bowel sounds. There was tenderness in the lower quadrants without rebound.

The WBC was 53.9 K/mcl with 84% neutrophils. The Hct was 36.1%. There was severe metabolic acidosis with an anion gap of 19, bicarbonate level of 12 mmol/L, lactic acid level of 3.6 mmol/L. The arterial blood gas demonstrated a pH of 7.11, CO2 of 16, and O2 of 150 on 2 liters of oxygen via nasal canula. The serum creatinine was 11.5 mg/dL. The K+ was 2.5 mmol/L, and Mg++ of 0.6 mg/dL. The INR was 2.1.

The patient was resuscitated with IV fluids, and placed on dopamine and later norepinephrine. She was also given intravenous ciprofloxacin 500 mg every 12 h, oral vancomycin 250 mg every 6 h and IV metronidazole 500 mg every 6 h.

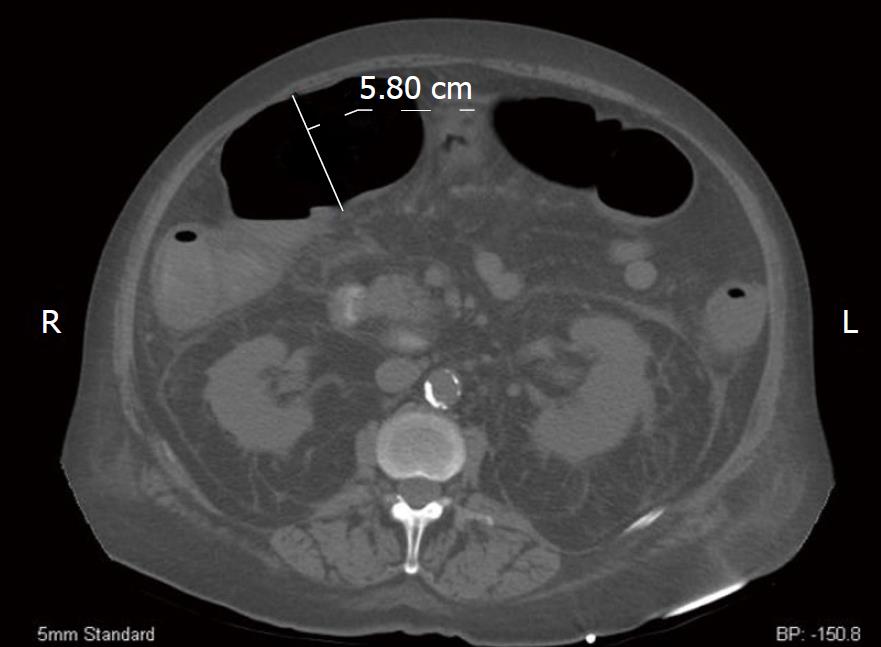

A CT of the abdomen and pelvis demonstrated circumferential wall thickening of the colon consistent with a pancolitis (Figure 1). The transverse colon was dilated to 5.8 cm.

Figure 1 Computerized tomography axial image of our patient.

We measured the patient’s transverse colon at 5.80 cm. Additionally, perinephric fluid is markedly evident bilaterally.

The patient did not improve despite treatment over the next 36 h. The WBC rose to 62.4 K/mcl. There was no other source of infection. Blood, urine and stool cultures were negative. The cytotoxicity assay for C. difficile on stool samples was also negative.

The surgery service was consulted for presumed toxic megacolon. A rigid sigmoidoscope was advanced to 25 cm from the anal verge. The mucosa appeared pink without pseudomembranes. The gastroenterology service next performed a colonoscopy, which demonstrated edematous mucosa with raised yellowish plaques consistent with pseudomembranous colitis in the sigmoid and descending colon. No biopsies were taken (Figure 2).

Figure 2 Colonoscopic image taken of the descending colon consistent with pseudomembranous colitis.

Medical treatment was continued and surgery was not offered at this time. Vancomycin 500 mg enemas every 12 h were added to the regimen. On subsequent stool samples the cytotoxicity assay for C. difficile was positive.

The patient’s blood pressure began to improve on the third day and IV pressors were discontinued. The patient was discharged after 23 d.

DISCUSSION

Concerning this case, we were presented with three questions: (1) What are the criteria for the diagnosis of toxic megacolon? (2) Is endoscopy necessary to confirm the diagnosis of C. difficile related toxic megacolon? and (3) When should surgery be performed for C. difficile related toxic megacolon? In order to answer these questions, we performed a systematic literature review. We searched the Web of Science, PubMed, MEDLINE, the Cochrane Library and Google Scholar for articles written between January 1990 and June 2009 using a combination of keywords and MeSH terminology “Clostridium difficile” and “toxic megacolon.” We limited our search to English language articles. We initially identified 55 articles. All articles were reviewed for content to determine relevance to the discussion. 17 articles were excluded because of lack of relevance to the topic. The citations of identified articles were also examined for additional publications. The total number of articles that were selected for our review was 37.

The diagnosis of toxic megacolon requires radiological evidence of colonic dilatation primarily involving the ascending or transverse colon. The degree of dilation is somewhat controversial - some using > 5 cm as a cut-off, while others require colonic dilation of > 6 cm to make the diagnosis[6,13,20-23].

CT is helpful in confirming the diagnosis of a toxic megacolon. CT findings commonly seen in patients with toxic megacolon are: pericolonic fat stranding, colonic wall thickening, absence or distortion of haustral folds, and ascites[13,15,24]. Other CT findings include the ‘target’ sign, which indicates mucosal hyperemia and submucosal edema and the ‘accordion’ sign, which is due to marked thickening of the haustral folds[24]. In a study by Hall et al[5], which reviewed 36 patients who had documented toxic megacolon at surgery, CT was accurate in 94% of cases.

In addition to colonic dilation, several clinical criteria must be fulfilled. The most accepted clinical criteria for toxic megacolon are derived from Jalan et al[19]. To establish the diagnosis of toxic megacolon three of the following four criteria should be present: fever > 101.5 F: HR > 120 beats/min: WBC > 10 500/mm^3: and anemia with hemoglobin or hematocrit level less than 60% of normal. In addition, the patient must have any one of the following four clinical findings: dehydration, electrolyte disturbance, hypotension or changes in mental status.

Endoscopy is seldom used to confirm the diagnosis of C. difficile related toxic megacolon since the diagnosis can be made by a combination of immunotoxin assay, clinical findings and imaging. An endoscopy may be dangerous, especially in a setting of fulminant colitis due to the increased risk of perforation[6,25]. A study by Johal et al[26], however encouraged the use of flexible sigmoidoscopy as a tool for the diagnosis of C. difficile toxic colitis when stool assays are negative. In their study 52% of patients who tested negative for C. difficile toxin assay had pseudomembranous colitis on flexible sigmoidoscopy.

Endoscopy is recommended for the diagnosis of C. difficile toxic colitis under the following conditions: (1) when there is a high level of clinical suspicion for C. difficile despite repeated negative laboratory assays; (2) when a prompt diagnosis is needed before laboratory results can be obtained; (3) when C. difficile infection fails to respond to antibiotic therapy or (4) for atypical presentations of C. difficile colitis such as in patients who present with ileus, acute abdomen, or leukocytosis without diarrhea[3,15,21].

In the treatment of C. difficile related toxic megacolon, aggressive medical therapy may help prevent surgical intervention in up to 50% of cases[13]. In a retrospective review by Imbriaco et al[27] 12 of the 18 patients (67%) with toxic megacolon due to C. difficile improved with medical therapy without the need for surgery.

The medical management of toxic megacolon includes oral vancomycin, IV metronidazole, bowel rest, bowel decompression, and replacement of fluids and electrolytes[13,18,21]. Some authors note that adequate intracolonic concentrations of vancomycin may not be achieved with oral vancomycin because of poor intestinal motility. Therefore, vancomycin enemas have been recommended; however enemas may fail to treat right-sided disease of the colon. Other alternatives include direct instillation of vancomycin by colonoscopy, colostomy or ileostomy[28].

The dilated colon may be decompressed with nasogastric suction and frequent repositioning of the patient[13]. Some authors recommend prone positioning for 10 to 15 min every 2 to 3 h allowing the passage of flatus. Panos et al[22] presented two cases where bowel decompression was successfully achieved with the knee-chest position.

Colonic decompression can also be achieved with a colonoscopy. Shetler et al[29] reviewed seven patients with toxic megacolon due to C. difficile who underwent decompressive colonoscopy and intracolonic perfusion of vancomycin. The authors found that 57% of the patients had complete resolution of toxic megacolon. Their reported data suggested that decompressive colonoscopy may be safe and effective in the medical treatment of toxic megacolon although the number of patients in this study was small. Other authors suggest that endoscopic decompression may worsen disease[21]. Colonoscopy may cause further dilation of the colon leading to impaired blood supply to the colon wall, increasing the risk of perforation and translocation of bacteria[13,21].

Management of toxic megacolon also includes with holding medications that slow intestinal motility. These medications include anticholinergics, antidepressants, antidiarrheals, and narcotics[6,13,30].

Surgical intervention may be necessary in up to 80% of patients with toxic megacolon due to C. difficile colitis[22]. Indications for surgery include: perforation, progressive dilation of the colon, lack of clinical improvement over the first 48-72 h and uncontrolled bleeding[9,13,21,26,31,32]. Ausch et al[31] evaluated 70 patients who had surgery for toxic megacolon due to C. difficile colitis and found that the most common indication for surgery was progressive colonic dilation. Clinical deterioration (36%) and uncontrolled bleeding (4%) were other reasons the authors noted.

The mortality rate for a colectomy has varies widely across studies. Byrne et al[14] retrospectively reviewed 73 patients who underwent colectomy for toxic megacolon due to C. difficile colitis between 1994 and 2005. The hospital mortality rate was 34% with a single intraoperative death. This study along with others have found that preoperative vasopressor requirement, endotracheal intubation, and altered mental status were significant predictors of mortality after colectomy[5,9]. Miller et al[33] retrospectively reviewed 49 patients who underwent colectomy for fulminant C. difficile colitis. The study found that the 30 d mortality rate was 57%, with an in-hospital morality rate of 49%. The 5 year survival rate for those who lived past 30 d from a colectomy was 38%.

The surgical procedure of choice for toxic megacolon is total colectomy with preservation of rectum and diverting ileostomy[6,7,13,31]. Outcomes are worse if a partial colectomy is performed, perhaps owing to residual diseased bowel left in place[3,4,29,34]. Grundfest-Broniatowski et al[35] reviewed 21 studies between 1976 and 1994. They reported a 24% mortality rate for subtotal colectomy compared to 40% for sigmoid resection alone. In a study by Koss et al[25], total colectomy resulted in a lower mortality rate (11%) compared to those with a left hemicolectomy (100%).

It must be emphasized that clear standardized indications for surgery in patients with toxic megacolon due to C. difficile colitis do not currently exist. In several articles reviewed, surgery was performed only in patients who had signs of systemic toxicity such as shock requiring vasopressors, multisystem organ failure or peritonitis[4,14,16,31,36]. It is interesting to speculate that mortality rates might be improved if patients were operated on earlier in the course of their illness, before signs of organ failure set in. Lamontagne[37] advised surgery for patients with WBC > 50 K/mcl and lactate levels > 5 mmol/L as these patients were likely to die within 30 d of ICU admission without surgery.

In conclusion, toxic megacolon is a complication of C. difficile colitis. The diagnosis is made when colonic dilation is at least > 5 cm. CT is helpful in establishing the presence of toxic megacolon by demonstrating wall thickening and distortion of haustra. The criteria described by Jalan et al[38] should be used in making the diagnosis. Patients should have aggressive medical management and daily abdominal X-rays. Patients with an ileus should be given rectal vancomycin as well - even though there is a lack of evidence-based studies to confirm its efficacy. Surgery should be considered if there is progressive colonic dilation or if clinical improvement is not noted within 2 to 3 d.