Published online Aug 16, 2010. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v2.i8.288

Revised: June 24, 2010

Accepted: July 1, 2010

Published online: August 16, 2010

AIM: To evaluate the efficacy of retrograde observation of the esophagus, pharynx, larynx and lingual root.

METHODS: With the beagle dog under anesthesia, the anterior wall of the stomach was fixed on the abdominal wall in a similar way to percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy. The gastrointestinal scope was inserted via a 12 mm laparoscopic port for subsequent retrograde observation from stomach to the oral cavity.

RESULTS: With this technique, direct observation of gastric cardia was possible without restriction. The cervical esophagus was dilated well, also allowing clear observation of the hypopharyngo-esophageal junction. If the tongue was manually pulled out forward, observation of the lingual root was possible.

CONCLUSION: This procedure is easy and effective for pre-treatment evaluation of the feasibility of endoscopic resection in cases of superficial carcinoma of head and neck.

- Citation: Honda M, Hori Y, Shionoya Y, Nakada A, Sato T, Kobayashi T, Shimada H, Kida N, Nakamura T. Observation of the esophagus, pharynx and lingual root by gastrointestinal endoscopy with a percutaneous retrograde approach. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2010; 2(8): 288-292

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v2/i8/288.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v2.i8.288

Recent advances in the devices for gastrointestinal endoscopy have enabled detailed observation of the oral cavity, pharynx and larynx[1,2]. Screening by means of narrow band imaging especially can detect minute changes in the vascular structure on the mucosal surface, making it easier to diagnose superficial tumors of the pharynx and larynx difficult to find in the past[3-5]. Since detection of early lesions has become possible, attempts have been made to apply endoscopic mucosal resection, previously used for treatment of gastric early stage carcinomas or polyps, to the pharynx and larynx. This technique is promising as a means of function-preserving treatment of pharynx and larynx lesions[6]. However, the orally inserted gastrointestinal endoscope has a limitation in the scope of visual field and observation of the anterior wall of mesopharynx and the lingual root is particularly difficult with this technique[6,7].

We recently conducted an experiment using dogs in which a gastrointestinal endoscope was inserted percutaneously into the stomach followed by retrograde observation of the stomach, esophagus, pharynx, larynx, lingual root and tongue. This paper will discuss and report on the procedure for simple insertion of a gastrointestinal endoscope and retrograde observation with the thus inserted endoscope.

The upper gastrointestinal endoscope used was the Olympus Endoscopic System (GIF-XQ240; Olympus Optical Co, Ltd., Tokyo Japan). It was used in combination with a gastric wall lifting and fixing tool (Ideal Lifting, Olympus Optical Co, Ltd., Tokyo Japan) for percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) and with a laparoscopic camera port 12 mm (Ethicon Endo-surgery, Inc., Cincinnati, OH, USA).

One beagle dog (male, 15 mo old, weighing 9.5 kg) was used for this experiment. The dog was preoperatively anesthetized with an intramuscular injection of atropine sulfate 0.05 mg/kg, ketamine hydrochloride 15 mg/kg and xylazine hydrochloride 3 mg/kg. First, the gastrointestinal endoscope was orally inserted followed by sufficient aeration within the stomach. In the similar way to PEG, the anterior wall of the gastric body was fixed on the abdominal wall at 2 points. A 1.5 cm skin incision was made between the two fixed points followed by incision of subcutaneous tissue and the gastric wall immediately below it to reach into the stomach. A 12 mm laparoscopic port was inserted and the endoscope was inserted via this port for subsequent retrograde observation of the stomach, esophagus, pharynx, larynx and tongue (Figure 1). The usefulness and safety of endoscopic observation with this approach were evaluated.

The protocol for this study was prepared in accordance with the “Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals” published by the National Institute of Health (NIH Publication No. 85-23, revised 1985) and was approved by the Kyoto University Animal Experiment Committee.

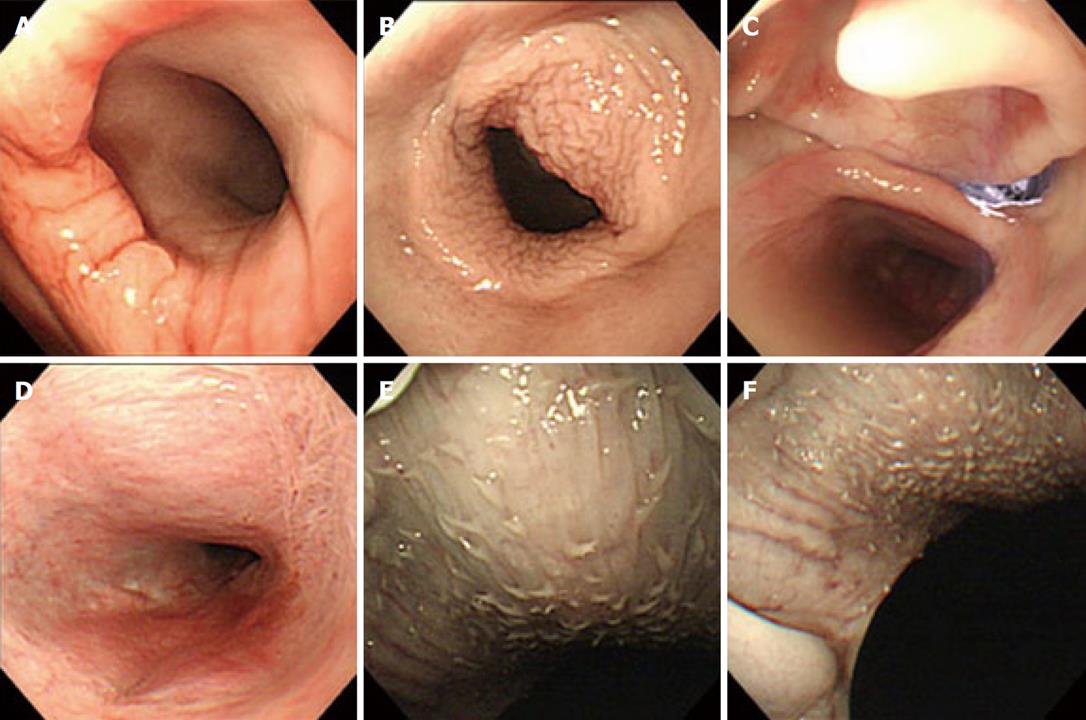

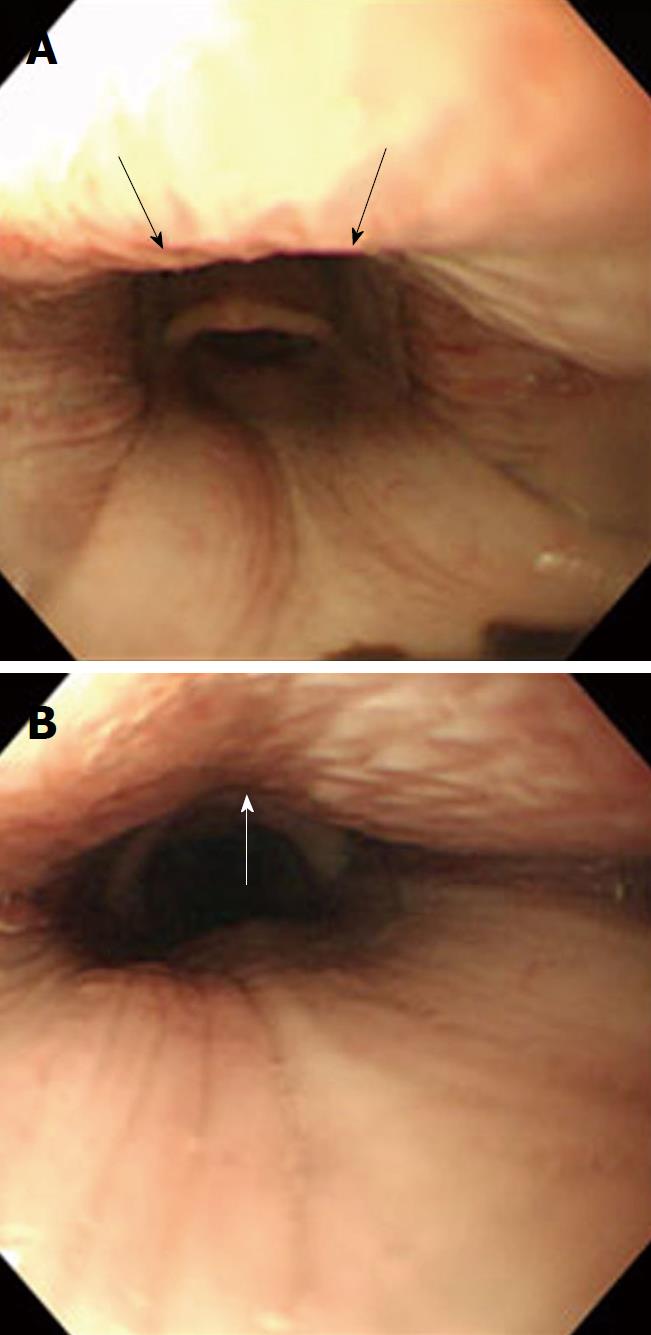

The steps of observation with this technique and image findings are presented. With conventional endoscopic techniques, the endoscope is usually inverted at the gastric cardia. With our technique, direct observation of this area was possible without restriction (Figure 2A). The endoscope was then advanced in a retrograde fashion beyond the esophagogastric junction into the esophagus and reached the cervical esophagus. The cervical esophagus could be dilated well, also allowing clear observation of the hypopharyngoesophageal junction (Figure 2B). The endoscope then entered the pharynx, enabling observation of the hypopharynx and the laryngeal surface of the epiglottis (Figure 2C). If the endoscope was further advanced, it reached epipharynx and nasal cavity (Figure 2D). If the endoscope was advanced towards the oral cavity, observation of the soft palate was possible. If the tongue was manually pulled out forward, observation of the lingual root was possible (Figure 2E and F). However, observation of the epiglottic vallecula was difficult because the epiglottis served as an obstacle. For comparison, the images of the lingual root observed by the per-oral approach are shown in Figure 3. As it was a dead angle of the endoscope, the lingual root is an unclear image.

The time taken from completion of anesthesia to the start of observation was about 30 min. At the end of observation, the camera port was removed and the wounds in the gastric and abdominal wall were closed by suturing. Blood loss was small, requiring no infusion or additional anesthetic. On the day following surgery, oral ingestion of diet was resumed. The dog is currently in good condition, 2 mo after surgery.

As described above, we devised a technique of percutaneous insertion of an endoscope into the stomach for subsequent retrograde observation. This technique allowed easy observation of the lingual root and epipharynx which are the dead angle during ordinary anterograde observation via the oral route. Furthermore, the gastric cardia, esophagogastric junction and the cervical esophagus could also be observed well without restriction of the visual field.

Recently, the accuracy of diagnosis using gastroenterological endoscopy devices in combination with narrow band imaging has improved, making it possible to detect carcinomas of the pharynx and larynx at early stages[1-4]. Following such improvement, endoscopic mucosal resection as a less invasive means of treatment while preserving the head/neck function has begun to be introduced clinically, attracting large expectations[5-7]. As treatment of pharyngeal/laryngeal carcinomas tends to be accompanied by significant loss of pharyngeal/laryngeal functions due to adverse events arising from chemoradiotherapy or surgery[8-10], evaluation of the efficacy of endoscopic mucosal resection and arguments about cases indicated for this procedure will increase in importance. Endoscopic treatment requires precise determination of the scope of the tumor-affected area. Needless to say, endoscopic resection is not possible in cases where the lesion has spread beyond the endoscopically visible range. With anterograde endoscopic observation via the oral route, observation is quite difficult at the anterior wall of mesopharynx, particularly the lingual root. In cases where the tumor has undergone intraepithelial spread in this area, endoscopic evaluation is difficult. In the present study, we evaluate the extent to which observation of lingual root would be possible with retrograde endoscopic observation. When the tongue was manually pulled forward, a good visual field was obtained, allowing sufficient observation of the lingual root. So far as observation of the epiglottic vallecula is concerned, anterograde observation seems more useful. So, it seems advisable to determine the scope of a lesion using a combination of endoscopic observation in two directions (anterograde and retrograde). This approach also seems to be useful for pre-treatment evaluation of the feasibility of endoscopic resection in cases of superficial carcinoma of the nasopharyngeal anterior wall and as a means of resecting such lesions[6].

This procedure involves incision of the abdominal and gastric wall and is therefore more invasive than conventional endoscopy. However, it can be performed safely and in a short time by fixing the gastric wall with the use of Ideal Lifting, a device for PEG. The safety of PEG has already been established and it is now used widely at many medical facilities[11,12]. The procedure we have devised is also advantageous in that the use of this procedure is not limited to particular facilities or surgeons.

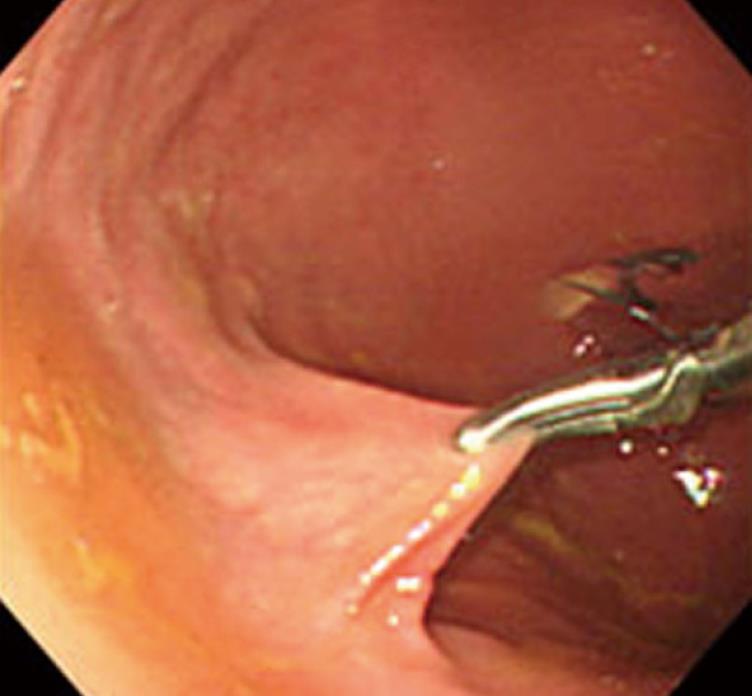

Although further evaluation of usefulness and safety in animal studies is needed, the use of this procedure for creation of multiple port holes will also enable percutaneous intragastric surgery with forceps for laparoscopic surgery (Figure 4). Another possibility with this procedure is that it may be used for treatment of superficial tumors of the cardia and esophagogastric junction where endoscopic mucosal resection has conventionally been difficult.

Recently, the accuracy of diagnosis using gastrointestinal endoscope in combination with narrow band imaging has been improved, making it possible to detect carcinomas of the pharynx and larynx at early stages. Clinicians have been tried to apply endoscopic mucosal resection, previously used for treatment of gastric early stage carcinomas or polyps, to lesions of the pharynx and larynx. This technique is promising as a less invasive and function-preserving treatment of pharynx and larynx lesions. However, the orally inserted an endoscope has a limitation, dead angle, in the scope of visual field: the anterior wall of mesopharynx and the lingual root.

This article described by first time an endoscopic procedure to correctly and completely evaluate those more difficult to explore areas in pharynx.

Innovation of our technique is the percutaneous insertion of an endoscope into the stomach for subsequent retrograde observation. This technique allowed easy observation of the lingual root and epipharynx which are the dead angle during ordinary anterograde observation via the oral route. No articles explained this method, previously.

This procedure will develop and become to enable percutaneous intragastric surgery with laparoscopic devices in future.

The retrograde observation: a gastrointestinal endoscope is inserted percutaneously into the stomach, and mesopharynx and the lingual root are observed passing esophagus from stomach. This route is the opposite direction to conservative method.

Reviewer’s comments: This manuscript described by first time an endoscopic procedure to correctly and completely evaluate those more difficult to explore areas in pharynx. Authors develop the technique via retrograde access by means of endoscopic gastrostomy insertion and successfully achieved to evaluated the target structures. This pre-clinical evaluation of the technique could have a promising future since the instruments used by authors are widely available in almost every hospital. This study is very interesting and feasible to new thrapeutic world.

Peer reviewers: Shinji Tanaka, MD, PhD, Professor, Department of Endoscopy, Hiroshima University Hospital, 1-2-3 Kasumi, Minami-ku, Hiroshima 734-8551, Japan; Alfredo José Lucendo, MD, PhD, Department of Gastroenterology, Hospital General de Tomelloso, Vereda de Socuéllamos, s/n, Tomelloso 13700, Spain

| 1. | Katsinelos P, Kountouras J, Chatzimavroudis G, Zavos C, Beltsis A, Paroutoglou G, Kamarianis N, Pournaras A, Pilpilidis I. Should inspection of the laryngopharyngeal area be part of routine upper gastrointestinal endoscopy? A prospective study. Dig Liver Dis. 2009;41:283-288. |

| 2. | Muto M, Nakane M, Katada C, Sano Y, Ohtsu A, Esumi H, Ebihara S, Yoshida S. Squamous cell carcinoma in situ at oropharyngeal and hypopharyngeal mucosal sites. Cancer. 2004;101:1375-1381. |

| 3. | Ugumori T, Muto M, Hayashi R, Hayashi T, Kishimoto S. Prospective study of early detection of pharyngeal superficial carcinoma with the narrowband imaging laryngoscope. Head Neck. 2009;31:189-194. |

| 4. | Orita Y, Kawabata K, Mitani H, Fukushima H, Tanaka S, Yoshimoto S, Yamamoto N. Can narrow-band imaging be used to determine the surgical margin of superficial hypopharyngeal cancer? Acta Med Okayama. 2008;62:205-208. |

| 5. | Piazza C, Dessouky O, Peretti G, Cocco D, De Benedetto L, Nicolai P. Narrow-band imaging: a new tool for evaluation of head and neck squamous cell carcinomas. Review of the literature. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital. 2008;28:49-54. |

| 6. | Iizuka T, Kikuchi D, Hoteya S, Yahagi N, Takeda H. Endoscopic submucosal dissection for treatment of mesopharyngeal and hypopharyngeal carcinomas. Endoscopy. 2009;41:113-117. |

| 7. | Muto M, Morita S, Chiba T. [Diagnosis and treatment for superficial cancer in the oropharynx and hypopharynx: new strategy of early detection and minimally invasive treatment]. Nippon Shokakibyo Gakkai Zasshi. 2009;106:1291-1298. |

| 8. | Abouzeid WM, Mokhtar SA, Mahdy NH, El Kwsky FS. Quality of life of patients with oral and pharyngeal malignancies. J Egypt Public Health Assoc. 2009;84:299-329. |

| 9. | Licitra L, Bernier J, Grandi C, Merlano M, Bruzzi P, Lefebvre JL. Cancer of the oropharynx. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2002;41:107-122. |

| 10. | Parsons JT, Mendenhall WM, Stringer SP, Amdur RJ, Hinerman RW, Villaret DB, Moore-Higgs GJ, Greene BD, Speer TW, Cassisi NJ. Squamous cell carcinoma of the oropharynx: surgery, radiation therapy, or both. Cancer. 2002;94:2967-2980. |

| 11. | Campoli PM, Cardoso DM, Turchi MD, Ejima FH, Mota OM. Assessment of safety and feasibility of a new technical variant of gastropexy for percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy: an experience with 435 cases. BMC Gastroenterol. 2009;9:48. |

| 12. | Cruz I, Mamel JJ, Brady PG, Cass-Garcia M. Incidence of abdominal wall metastasis complicating PEG tube placement in untreated head and neck cancer. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;62:708-711; quiz 752, 753. |