INTRODUCTION

Esophagitis dissecans superficialis (EDS) is a rare endoscopic finding characterized by sloughing of large fragments of esophageal mucosal lining[1]. In Figure 1A, an endoscopic image in our institute shows the typical features of EDS with vertical fissures and sloughing of whitish superficial epithelium. In 1892, Rosenberg coined the term “EDS” to describe this entity[2]. Its usual symptoms are dysphagia, odynophagia and heartburn. Hematemesis or vomiting esophageal casts occurs rarely. The causes of EDS include idiopathy[1,3], medications (bisphosphonates[4], nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs[1] and potassium chloride), hot beverages, chemical irritants, celiac disease[5], collagen diseases[6] and autoimmune bullous dermatoses. Recently, the pathophysiology and strong relationship between EDS and autoimmune bullous dermatoses have gained remarkable attention. We review these topics with the presentation of our experiences.

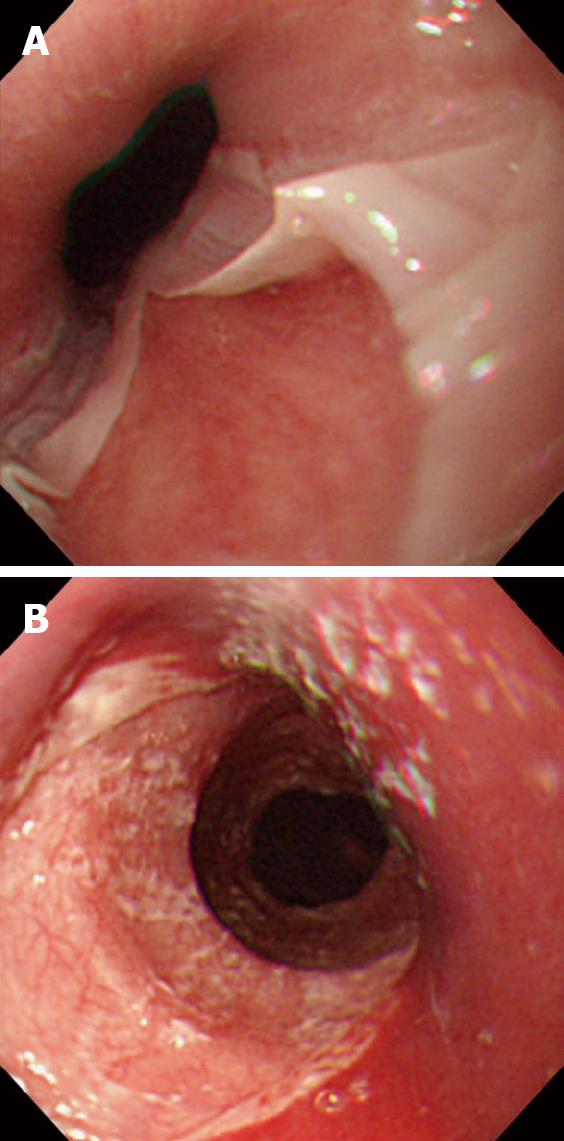

Figure 1 Endoscopic view of esophagitis dissecans superficialis.

A: With diffuse sloughing mucosa of the lower esophagus in a 76-year-old woman presenting hematemesis, and the cause was idiopathic; B: with longitudinal sloughing mucosa from upper to mid esophagus in a 67-year-old woman with mucocutaneous type pemphigus vulgaris, note fine whitish fragments of sloughed mucosa, and the index value for anti-desmoglein 3 antibody by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay was over 1280 (normal value < 7).

PEMPHIGUS

Pemphigus is a rare autoimmune disease that causes blistering of the skin and oral mucosa. It is caused by antibody-mediated autoimmune reaction to desmogleins, desmosomal transmembrane glycoproteins of keratinocytes, leading to acantholysis[7,8]. There are two major types of pemphigus: pemphigus vulgaris (PV) and pemphigus foliaceus (PF). There are two subtypes of PV: the mucosal-dominant type with mucosal lesions but minimal skin involvement and the mucocutaneous type with extensive skin blisters and erosions in addition to mucosal involvement[7]. Patients with PF have scaly erosions of the skin but not of the mucosa. The clinical phenotype of PV is determined by the distribution of desmoglein 1 and desmoglein 3[7]. The desmoglein compensation theory can explain the localization of blisters[7]. Desmoglein 3 is expressed throughout the oral mucosa but only in the basal and immediate suprabasal layers of epidermis. Conversely, desmoglein 1 is expressed throughout the epidermis more intensely in the superficial oral mucosa but weakly in the deep layers. Anti-desmoglein 1 or anti-desmoglein 3 autoantibodies inactivate only the corresponding desmoglein and functional desmoglein 1 or desmoglein 3 alone is sufficient for cell-cell adhesion[7,8]. In the mucosa therefore, desmoglein 1 is unable to compensate the loss of desmoglein 3 function because it is weakly expressed, particularly in the deep layer. This pathophysiology explains why anti-desmoglein 3 alone can cause blister formation in the mucosa. Patients with mucosal-dominant PV have anti-desmoglein 3 antibodies which cause mucosal blisters whereas those who also have anti-desmoglein 1 antibodies have skin involvement[7,8].

The diagnostic hallmark of PV is acantholysis with bulla formation in the suprabasal region and the pathognomonic “a row of tombstones-like” basal cell layer[9]. Immunological examinations confirm the diagnosis[10]. For direct immunofluorescence (DIF) to show intercellular IgG and C3 deposits, a biopsied specimen should be placed in special media and commercially available systems are applied to indirect immunofluorescence (IIF). Until recently, DIF or IIF was the standard method of detecting antibodies that bind to the keratinocytes. However, recent studies have shown that enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) to detect anti-desmoglein 1 and anti-desmoglein 3 antibodies is much simpler and more quantifiable than immunofluorescence[7]. ELISA scores which show parallel fluctuations with the activity of PV are useful for monitoring disease activity[7]. The treatment consists of systemic steroids, megadose pulse steroids, immunosuppressive drugs, plasmapheresis and intravenous immunoglobulin. Topical treatment is applied to reduce pain and to prevent and treat secondary infections. In refractory PV, rituximab, a chimeric monoclonal antibody against CD20, can be applied[10].

ASSOCIATION OF EDS AND PV

The oral mucosa and skin are common sites of PV and other mucosal surfaces with stratified squamous epithelium such as nasopharynx, esophagus, conjunctiva, anus and vagina are also involved[10]. Oral lesions precede skin lesions in 70% of PV cases and when skin is already involved, concomitant oral lesions are encountered in 90% of cases[11]. As for esophageal involvement, prevalence of esophageal involvement was considered quite rare because of the little recognition of the importance of esophageal lesions of PV among dermatologists and inexperience of such lesions for most endoscopists. Such involvement may be under-recognized or misdiagnosed as peptic esophagitis. Since the first case of esophageal involvement of PV was reported by Raque et al[12] in 1970, such cases have been increasingly reported. Esophageal symptoms of PV patients include dysphagia, odynophagia, heartburn, regurgitation, chest pain and hematemesis[11-16]. Recent endoscopic studies have shown a relatively higher incidence (46%-87%) of esophageal lesions among PV patients than ever expected[13-16]. The studies have indicated a strong correlation between esophageal symptoms and endoscopic detection of esophageal involvement. Endoscopic features range from mild to severe forms including local erythema, red erythematous longitudinal lines, blisters, erosions, ulcers and EDS. It has been obvious that dysphagia and odynophagia may indicate esophageal involvement by PV; therefore, endoscopy is indicated for esophageal symptoms. PV patients with exclusive esophageal involvement have been reported[17]. In addition, endoscopic examination is helpful to distinguish PV lesions from candidal, herpetic and peptic esophagitis which are frequent in PV patients receiving steroids and immunosuppressive drugs. It is also helpful to detect gastroduodenal peptic diseases before high dose steroid therapy.

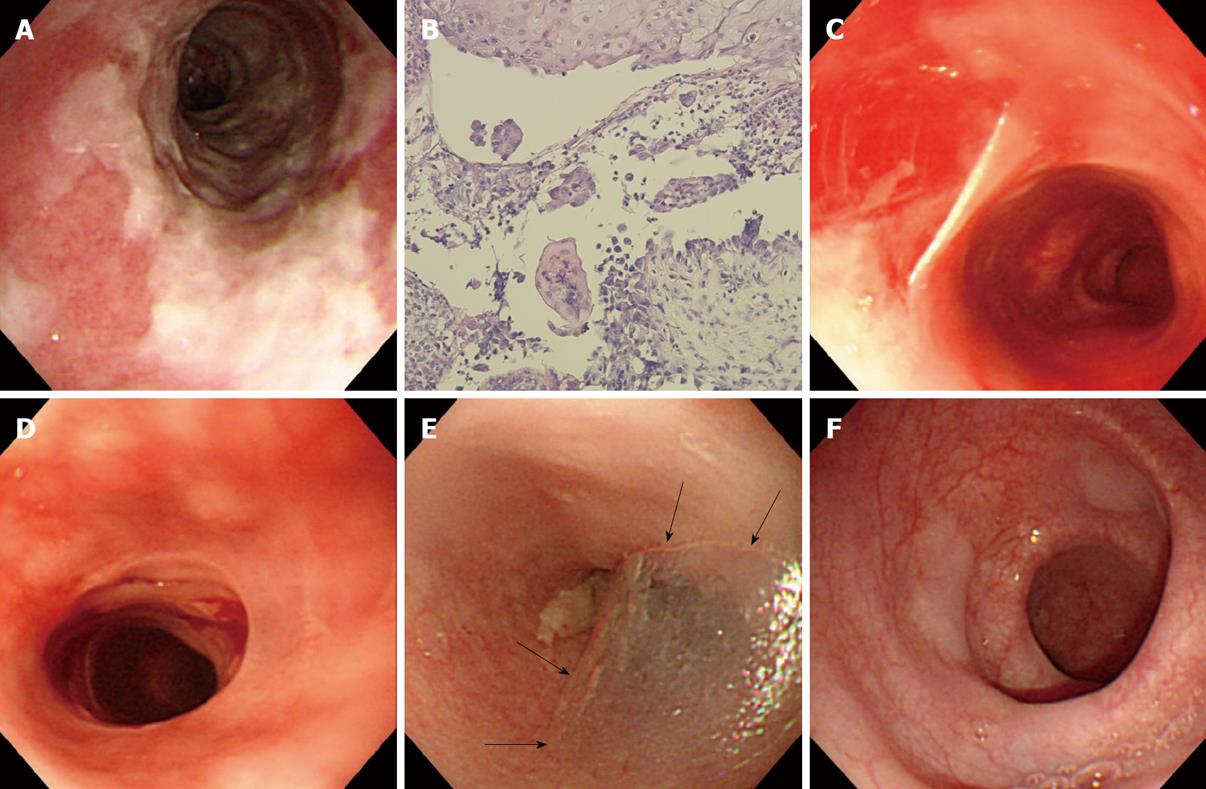

Among various esophageal lesions in PV, dramatic presentations of EDS with vomiting esophageal casts were documented before the endoscopic era[18,19]. Six cases of EDS associated with PV have been well documented in the English literature[18-23]. Four out of six cases underwent endoscopy at the initial episode. Endoscopic features of EDS have included stripped mucosa with bleeding[20], total desquamation of the esophageal mucosa without bleeding[21], long linear mucosal break[22] and vertical fissures and circumferential cracks with peeling, whitish mucosa with extensive bleeding and exudating esophagitis[23]. A typical endoscopic image of EDS associated with PV in our institute is shown in Figure 1B. Our patient had mucocutaneous type PV and remains well with immunosuppressive treatment. In Figure 2, sequential endoscopic images of various esophageal lesions including EDS in another patient with PV in our institute are depicted. The control of her disease activity was difficult despite intensive treatment and thus characteristic findings of diffuse erosion, EDS, bulla and webs appeared within a short period. There was a female predominance of the cases including our cases[23]. Cesar et al[23] have indicated that EDS associated with PV is an acute event and does not imply worsening of PV because PV was either in partial or total remission in reported cases. However, through our experience shown in Figure 2, we believe that EDS may be an acute on chronic event and a severe form of esophageal lesions in PV. As mentioned before, ELISA scores of anti-desmoglein 3 show parallel fluctuations with the activity of esophageal lesions of PV.

Figure 2 Endoscopic views of a variety of esophageal findings in a 71-year-old woman with mucosal-dominant pemphigus vulgaris.

A: Note esophagitis dissecans superficialis with extensive reddish erosion of the entire esophagus and whitish sheets of sloughed mucosa with the index value for anti-desmoglein 3 antibody of 1620; B: Histopathological examination of the esophageal mucosa, showing separation at the suprabasal level of epithelium. Note the formation of a row of tombstones-like basal cells that remain attached to the basement membrane (H&E, × 100); C: Esophagitis dissecans superficialis with sheets of sloughing mucosa in the mid esophagus with the index value for anti-desmoglein 3 antibody of 128; D: Sheets of sloughing mucosa presenting esophageal webs in the upper esophagus; E: A bulla (arrowheads) in the upper esophagus with the index value for anti-desmoglein 3 antibody of 145; F: Several slightly raised whitish blisters scattered in the lower esophagus.

There have been some concerns about endoscopic examination for patients of PV because of the potential risks of causing trauma to fragile esophageal mucosa by endoscopic procedure[24] and positive Nikolsky’s sign, stripping of the apparently normal mucosa on withdrawal of the biopsy forceps[25-28]. Trattner et al[29] have documented that DIF studies of the biopsied esophageal mucosa were positive for PV lesions even in the normal macroscopic appearance of the esophagus in PV patients. Therefore, most PV patients may have the potential risk of positive Nikolsky’s sign in the esophagus. With respect to those risks, most endoscopic examination has been undertaken safely in skilled hands[14,16,30]. For the treatment of esophageal PV lesions and/or the prevention of potential injury after biopsies, mucosa-protecting agents and antacid agents may be helpful in addition to steroids. It is mandatory that endoscopists give the pathologists adequate biopsy specimens which include basement membrane but it is sometimes difficult to perform such a biopsy because of the tangential position of endoscope and biopsy forceps inside the esophagus. Galloro et al[30] have indicated that a commercially available rocking biopsy forceps provide adequate sampling which leads to demonstrating suprabasal acantholysis and making the definite diagnosis of esophageal involvement. Performing biopsies at the junction between floor and roof of the blister and adjacent, not blistering mucosa is also recommended[30].

ASSOCIATION OF EDS AND PEMPHIGOID

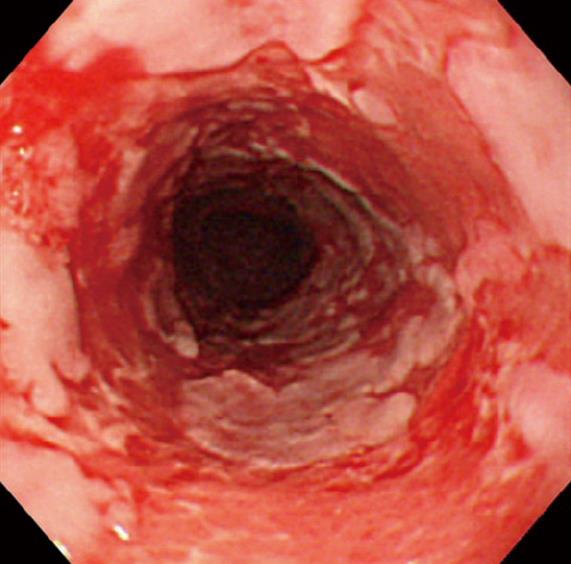

EDS may also present in other autoimmune bullous dermatoses including pemphigoid. Pemphigoid is a group of autoimmune subepithelial blistering diseases, subclassified into mucous membrane pemphigoid (MMP), also known as cicatricial pemphigoid and bullous pemphigoid (BP)[31]. MMP is characterized by linear deposition of IgG and complement factor 3 along epithelial basement membrane zone resulting in subepidermal blisters and erosions[31]. Mucous membrane involvement is common, primarily of the oral mucosa and conjunctiva, but may also include the nasopharynx, esophagus and genital mucosa[32]. Esophageal bullae or erosions occur in 8 percent of cases[32]. Esophageal symptoms with pemphigoid are similar to those with PV. Since the first case of EDS of MMP was reported by Foroozan et al[33] in 1967, such cases have been rarely reported[34]. These lesions heal with scarring, leading to the formation of webs and strictures[35,36]. Esophageal webs represent an early stage of the involvement whereas strictures are more likely to represent an advanced stage secondary to scarring and fibrosis[37], sometimes requiring endoscopic dilatation or surgery[38,39]. An endoscopic image of extensive EDS associated with MMP in our institute is shown in Figure 3. BP is characterized by subepidermal blisters forming large, tense bullae. Sites involved include the oral cavity, anus and genital mucosa. Although the involvement of esophagus is much less common with pemphigoid than pemphigus[32], certain cases of BP have reminded us that diseases of the “outside” skin may also be manifest on the “inside” skin of the esophagus[40-43]. We should be aware that endoscopic contact may cause esophageal bullae in BP[42,43]. Treatment of pemphigoid mainly consists of steroids.

Figure 3 An endoscopic view of an 84-year-old man with mucous membrane pemphigoid.

Note esophagitis dissecans superficialis with extensive reddish erosion of the entire esophagus and whitish sheets and fragments of sloughed mucosa.

CONCLUSION

Autoimmune bullous dermatoses such as PV and pemphigoid frequently present with various types of esophageal lesions including EDS, a severe form of the involvement. Recognition of the esophageal involvement in PV and pemphigoid may alter the management, requiring close teamwork between dermatologists and endoscopists. As the esophageal mucosa is fragile with potential Nikolsky’s sign, endoscopic examination should be performed carefully in skilled hands for esophageal symptoms to evaluate the correct diagnosis and allow prompt treatment.

Peer reviewers: Young-Tae Bak, MD, PhD, Professor, Division of Gastroenterology, Department of Internal Medicine, Korea University, Guro Hospital, 97 Gurodong-gil, Guro-gu, Seoul 152-703, South Korea; Jaekyu Sung, MD, PhD, Assistant Professor, Department of Internal Medicine, Chungnam National University Hospital, 33 Munhwa-ro, Jung-gu, Daejeon 301-721, South Korea

S- Editor Zhang HN L- Editor Roemmele A E- Editor Liu N