Published online Dec 16, 2010. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v2.i12.413

Revised: September 27, 2010

Accepted: October 4, 2010

Published online: December 16, 2010

Non-peptic, non-hypertrophic pyloric stenosis has rarely been reported in pediatric literature. Endoscopic pyloric balloon dilation has been shown to be a safe procedure in treating gastric outlet obstruction in older children and adults. Partial gastric outlet obstruction (GOO) was diagnosed in an infant by history and confirmed by an upper gastrointestinal series (UGI). Abdominal ultrasonography and computed tomography scan excluded idiopathic hypertrophic pyloric stenosis, abdominal tumors, gastrointestinal and hepato-biliary-pancreatic anomalies. Endoscopic findings showed a pinhole-sized pylorus and did not indicate peptic ulcer disease, Helicobacter pylori infection, antral web, or evidence of allergic and inflammatory bowel diseases. Three sessions of a step-wise endoscopic pyloric balloon dilation were conducted under general anesthesia and a fluoroscopy at two week intervals using catheter balloons (Boston Scientific Microvasive®, MA, USA) of increasing diameters. Repeat UGI after the first session revealed normal gastrointestinal transit and no intestinal obstruction. The patient tolerated solid food without any gastrointestinal symptoms since the first session. The endoscope was able to be passed through the pylorus after the last session. Although the etiology of GOO in this infant is unclear (proposed mechanisms are herein discussed), endoscopic pyloric balloon dilation was a safe procedure for treating this young infant with non-peptic, non-hypertrophic pyloric stenosis and should be considered as an initial approach before pyloroplasty in such presentations.

-

Citation: Karnsakul W, Cannon ML, Gillespie S, Vaughan R. Idiopathic non-hypertrophic pyloric stenosis in an infant successfully treated

via endoscopic approach. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2010; 2(12): 413-416 - URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v2/i12/413.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v2.i12.413

We recently read a very good review on Endoscopic balloon dilation for benign gastric outlet obstruction in adults by Kochhar R et al[1]. We would like to share our pediatric perspective how endoscopic balloon dilation was safely used to treat an infant with gastric outlet obstruction (GOO) of unknown cause, using guidelines similar to those suggested in that article.

Idiopathic hypertrophic pyloric stenosis (IHPS) is probably the most common cause of GOO in children which presents after birth, generally in the first 3 mo of life. Endoscopic pyloric balloon dilation (EPBD) has been shown to be a safe and effective procedure in treating gastric outlet obstruction in older children and adults[2-5]. An eighteen month old Caucasian boy had fever at the beginning of his illness, followed by persistent vomiting for a total of 3 wk. His physical examination revealed a weight of 9.21 kilograms (below 3rd percentile), height of 83.5 cms (on 75th percentile), normal vital signs, pallor, no acute distress, no palpable mass, no hepatosplenomegaly, and a non-tender, non-distended abdomen. A review of past medical history demonstrated a previously healthy infant with a viral-like episode following illness in all family members a few weeks prior to admission. The patient breast fed until the age of 12 mo when solid food was introduced and subsequently advanced. There was no history of food or drug allergy, gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding, other gastrointestinal symptoms, consumption of raw meat and fish or any history of foreign body or caustic ingestion. Intravenous fluid was given to correct a mild degree of dehydration.

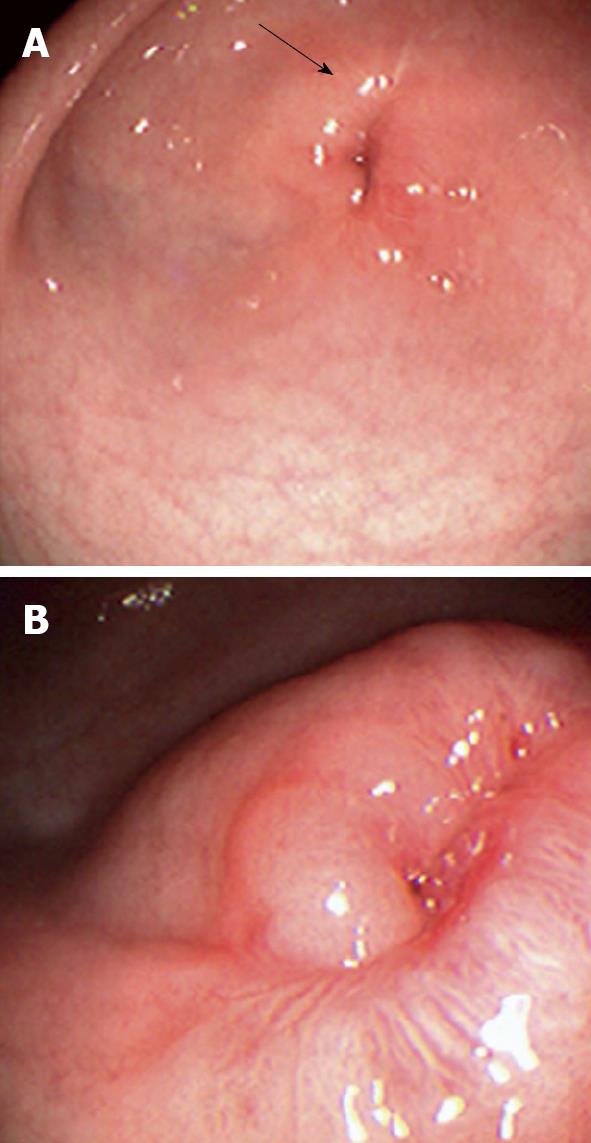

On admission his laboratory analyses showed mild hypochloremic metabolic alkalosis and moderate iron deficiency anemia without eosinophilia. Stool occult blood had been negative on several occasions. Gastric distension was noted on plain abdominal series. A pyloric ultrasound revealed redundancy of the antral walls and duodenum. Pyloric channel length was 14 mm. But its width was unmeasurable due to an inability to identify the pylorus in the transverse plane. GOO was observed on an upper GI series (Figure 1). Computed tomography (CT) images of the abdomen following the administration of intravenous and oral contrast media showed no evidence of an abnormal mass in the stomach or duodenum or any external mass compressing the pylorus. An upper endoscopy (EGD) demonstrated mild erythema of the distal esophagus, markedly enlarged, thickened, and asymmetric folds with a pin-hole opening that did not allow the passage of a Pentax-EG-1840 endoscope. A normal granulocytic oxidative burst was reported from dihydrorhodamine (DHR) flow cytometry assays which was inconsistent with the diagnosis of CGD. The patient received total parenteral nutrition, 15 mg daily of oral Prevacid®, iron therapy, and a 5 d course of 2 grams per kg per day of methylprednisolone (to reduce pyloric edema). After 3 wk of Prevacid® a repeat EGD showed findings of thickened pylorus with pin-hole opening similar to the initial results (Figure 2). The pathologic report showed 1-2 eosinophils per high power field and no evidence of Helicobacter pylori, lymphoid follicles in the gastric mucosa, or granulomatous formation. Three sessions of EPBD with fluoroscopic guidance were conducted under general anesthesia over a period of 6 wk at two weeks intervals (Figure 3). Catheter balloons (Boston Scientific Microvasive®, MA, USA) of increasing diameters (first session at 6 mm and 8 mm, second session at 10 mm and 12.5 mm, and third session at 15 mm) were used to insert through the biopsy channel of a Pentax-EG-2731 endoscope and inflated with the use of a pressure gauge system for 60-120 s. The Pentax-EG-1840 endoscope was able to be passed through the pylorus after the first session. Pyloric and duodenal mucosa appeared normal. Repeat UGI series and gastric emptying scan after the third session were normal. The patient had eaten a regular diet and gained weight appropriately without vomiting and abdominal distention after a two year follow-up.

Although the child’s endoscopic findings are consistent with IHPS, the sonographic findings are inconsistent with this diagnosis. A group in Galveston described this as a condition of “burned-out IHPS” in children with less severe symptoms than those seen in classical IHPS. Left undiagnosed and untreated, the hypertrophied pylorus in these cases was thought to regress and cause fibrosis leading to pyloric stenosis. These children failed to thrive and often vomited prior to the diagnosis[6].

Other causes of GOO include antral web, gastric duplication, gastric volvulus, pyloric atresia, epidermolysis bullosa, congenital granulomatous disease (CGD), ectopic pancreas, caustic ingestion, bezoars, migration of gastrostomy tube balloons, infection (such as Helicobacter pylori, Anisakis simplex or anisakiasis), peptic ulcer disease (PUD), extramural compression, eosinophilic gastritis, Crohn disease, hematoma, gastroparesis, and solitary intestinal fibromatosis[2-5].

Achalasia of the pylorus is a possible diagnosis due to the quick response to EPBD in this child. Achalasia is primarily a motor disorder of the esophagus which presents as a functional obstruction at the lower esophageal sphincter (LES). The etiology is thought to be related to reduced function or numbers of postganglionic inhibitory ganglion cells following an inflammatory episode. Achalasia of the pylorus is rarely reported in the medical literature[7]. An inflammatory process in this condition is thought to predispose to persistent pylorospasm which leads to muscular hypertrophy. This is also proposed to be a mechanism that causes obstruction in IHPS. Castro et al reported a 12-year-old boy diagnosed with achalasia and IHPS attributed to nitric oxide (NO) absence. NO has been identified as the main inhibitory neurotransmitter in both the LES and the pyloric sphincter. Moreover, the absence of NO synthase in the LES and the pylorus has been implicated in the pathogenesis of IHPS and achalasia[8]. Williams reported three adult patients with acquired GOO and proposed achalasia of the pylorus as an etiology[7]. All were treated with partial gastrectomy and no obvious pathology could explain the cause of pyloric obstruction in these cases. Nine children (age 3 mo to 17 years) presented with a history of late-onset primary GOO of unknown etiology[9]. Eight of them underwent Heineke-Mikulicz pyloroplasty as a result of gastric dilatation with no intrinsic or extrinsic mechanical obstruction at the pylorus. Pneumatic dilation was used in two sessions to successfully dilate a pyloric obstruction in a four year old boy[9]. Pyloric achalasia was proposed as the etiology of the late-onset functional GOO in these cases[9]. Markowitz et al[10] suggested a pyloric channel ulcer as a cause of development of pyloric stenosis. Although pyloric ulcer was not observed in our patient during a thorough examination of the pyloric channel after Prevacid® therapy for 3 wk, the presence of antroduodenal inflammation and ulcer deformity or pyloric mucosal scarring was reported in most patients with peptic pyloric stenosis[3].

CGD is a hereditary disorder of granulocyte function which causes progressive multisystemic inflammation and pyloric obstruction. A previously healthy child with acute onset of GOO described by Varma et al[11] had normal pyloric histology on endoscopic biopsy, but a full thickness biopsy during laparotomy and the DHR study confirmed the diagnosis of CGD.

EPBD has been used to treat IHPS and other causes of GOO including a pyloric stricture secondary to caustic ingestion, peptic ulcer disease, and delayed gastric emptying[2-5]. Balloon dilatation was a successful alternative procedure to surgery in two infants with IHPS who had inadequate pyloromyotomy and in an 11-year-old boy with surgical damage to the vagus nerve. EPBD was used as a treatment after failed pyloromyotomy in children with hypertrophic pyloric stenosis[5]. The success of EPBD in treating pyloric stenosis or GOO is explained by a complete and longitudinal disruption of the seromuscular ring without any damage to mucosal integrity (tearing)[6].

Idiopathic pyloric stenosis is a rare condition. A “burned out” IHPS, achalasia of the pylorus, and peptic pyloric stenosis are strongly suggested, based on clinical history. We believe the late presentation of acquired pyloric stenosis may depend upon the timing of advancing feeds, food consistency, gastric accommodation, and prior acute illness predisposing to dysmotility. While pyloromyotomy is a recommended operation for IHPS and pyloroplasty in other surgical GOO, we propose that some children who do not fit into the ultrasonographic criteria for IHPS may be good candidates for EPBD.

Peer reviewers: Kenneth Kak Yuen Wong, MD, PhD, Assistant Professor, Department of Surgery, The University of Hong Kong, Queen Mary Hospital, Pokfulam Road, Hong Kong, China; Takayuki Yamamoto, MD, PhD, Inflammatory Bowel Disease Center, Yokkaichi Social Insurance Hospital, 10-8, Hazuyamacho, Yokkaichi 510-0016, Japan

S- Editor Zhang HN L- Editor Hughes D E- Editor Liu N

| 1. | Kochhar R, Kochhar S. Endoscopic balloon dilation for benign gastric outlet obstruction in adults. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;2:29-35. |

| 2. | Treem WR, Long WR, Friedman D, Watkins JB. Successful management of an acquired gastric outlet obstruction with endoscopy guided balloon dilatation. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1987;6:992-996. |

| 3. | Chan KL, Saing H. Balloon catheter dilatation of peptic pyloric stenosis in children. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1994;18:465-468. |

| 4. | Israel DM, Mahdi G, Hassall E. Pyloric balloon dilation for delayed gastric emptying in children. Can J Gastroenterol. 2001;15:723-727. |

| 5. | Heymans HS, Bartelsman JW, Herweijer TJ. Endoscopic balloon dilatation as treatment of gastric outlet obstruction in infancy and childhood. J Pediatr Surg. 1988;23:139-140. |

| 6. | Mulvihill SJ, Fonkalsrud EW. Pyloroplasty in infancy and childhood. J Pediatr Surg. 1983;18:930-936. |

| 8. | Castro A, Mearin F, Gil-Vernet JM, Malagelada JR. Infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis and achalasia: NO-related or non-related conditions? Digestion. 1997;58:596-598. |

| 9. | Lin JY, Lee ZF, Yen YC, Chang YT. Pneumatic dilation in treatment of late-onset primary gastric outlet obstruction in childhood. J Pediatr Surg. 2007;42:e1-e4. |

| 10. | Markowitz RI, Wolfson BJ, Huff DS, Capitanio MA. Infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis--congenital or acquired? J Clin Gastroenterol. 1982;4:39-44. |

| 11. | Varma VA, Sessions JT, Kahn LB, Lipper S. Chronic granulomatous disease of childhood presenting as gastric outlet obstruction. Am J Surg Pathol. 1982;6:673-676. |