Published online May 16, 2025. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v17.i5.101618

Revised: January 17, 2025

Accepted: April 11, 2025

Published online: May 16, 2025

Processing time: 233 Days and 13.2 Hours

Common variable immunodeficiency (CVID) is a primary antibody immunodeficiency disorder characterized by diminished IgG levels. Despite ongoing research, the precise pathogenesis of CVID remains unclear. Genetic factors account for only 10%-20% of cases, with an estimated incidence of 1 in 10000 to 1 in 100000, affecting individuals across all age groups.

We report the case of a 32-year-old man with CVID who presented with a chief complaint of “recurrent diarrhea and significant weight loss over the past 2 years”. Laboratory tests on admission showed fat droplets in stool, while other parameters were within normal ranges. Gastroscopy revealed a smooth gastric mucosa without bile retention or signs of Helicobacter pylori infection; however, the mucosa of the descending segment of the duodenum appeared rough. Further evaluation of the small intestine using computed tomography indicated no abnormalities. Finally, the whole-small bowel double-balloon enteroscopy (DBE) was performed, which revealed various phenotypic changes in the small intestinal mucosa. The patient was diagnosed with CVID, which improved after immunoglobulin therapy, with favorable follow-up outcomes.

Non-infectious enteropathy in CVID is rare. Therefore, DBE is essential for diagnosing small intestinal involvement in such cases.

Core Tip: We report a case of non-infectious common variable immunodeficiency (CVID) patient associated bowel disease with non-specific clinical manifestations, which is characterized by B-cell dysfunction and reduced levels of serum IgG. The disease is rare and the etiology and pathogenesis remain unknown, making it difficult to diagnose, thus resulting in high mortality. Whole small intestinal double balloon enteroscopy is helpful for early diagnosis and reveals the involvement of the whole small intestinal mucosa. This case emphasizes that timely diagnosis, effective intervention and follow-up management are essential to improve the outcome of CVID patients.

- Citation: He T, Fan MM, Zhang PQ, Zhang W, Fan D, Du LS, Tang M, Wan P, Song ZJ. Diverse phenotypic manifestations of small intestinal mucosa in non-infectious common variable immunodeficiency bowel disease: A case report. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2025; 17(5): 101618

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v17/i5/101618.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v17.i5.101618

Common variable immunodeficiency (CVID) is a primary antibody immunodeficiency disorder characterized by low IgG levels. Its clinical presentation is multifaceted, with prominent gastrointestinal symptoms particularly affecting the duodenum and distal ileum. Microscopic examination often reveals mucosal thinning, villous atrophy, congestion, and edema. However, few comprehensive reports have detailed the extent of small intestinal mucosal involvement and associated microscopic changes. In this study, we report a case of a patient with CVID primarily presenting with diarrhea. During diagnosis and treatment, a thorough evaluation of multiple systems was conducted, focusing specifically on double-balloon enteroscopy (DBE) to assess the entire small intestinal mucosa. Notably, a spectrum of mucosal lesions was identified, underscoring the phenotypic presentations of CVID heterogeneity. The following narrative offers a detailed explanation of this intriguing case.

A 32-year-old man was admitted to our department on May 14, 2023, with a chief complaint of “recurrent diarrhea and significant weight loss over the past 2 years”.

The patient reported recurrent diarrhea and significant weight loss over the past 2 years.

The patient’s medical history is unremarkable.

The patient had no history of substance abuse, consanguineous marriage with parental relatives, or familial genetic disorders.

Upon admission, the patient had a body mass index (BMI) of 18 kg/m2, indicating emaciation, with no other discernible positive clinical signs noted during the initial examination.

On the day of admission, laboratory tests revealed several abnormalities: Stool tests showed the presence of fat droplets; blood biochemistry indicated decreased levels of total protein (53.3 g/L; normal: 60-80 g/L), albumin (39.4 g/L; normal: 40-55 g/L), globulin (13.9 g/L; normal: 20-29 g/L), and immune proteins, including IgG (0.85 g/L; normal: 7.0-16.6 g/L), IgA (0.07 g/L; normal: 0.7-3.5 g/L), IgM (0.13 g/L; normal: 0.5-2.6 g/L), and complement C3 (0.67 g/L; normal: 0.8-1.5 g/L). Other parameters, including blood routine, liver and kidney function, pancreatic enzymes, blood glucose, electrolytes, and thyroid function, were within normal ranges.

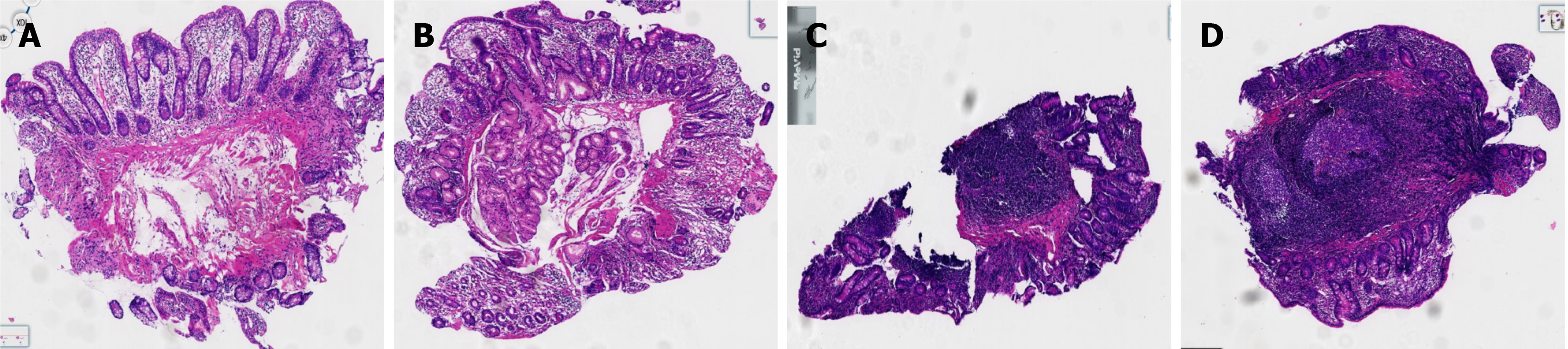

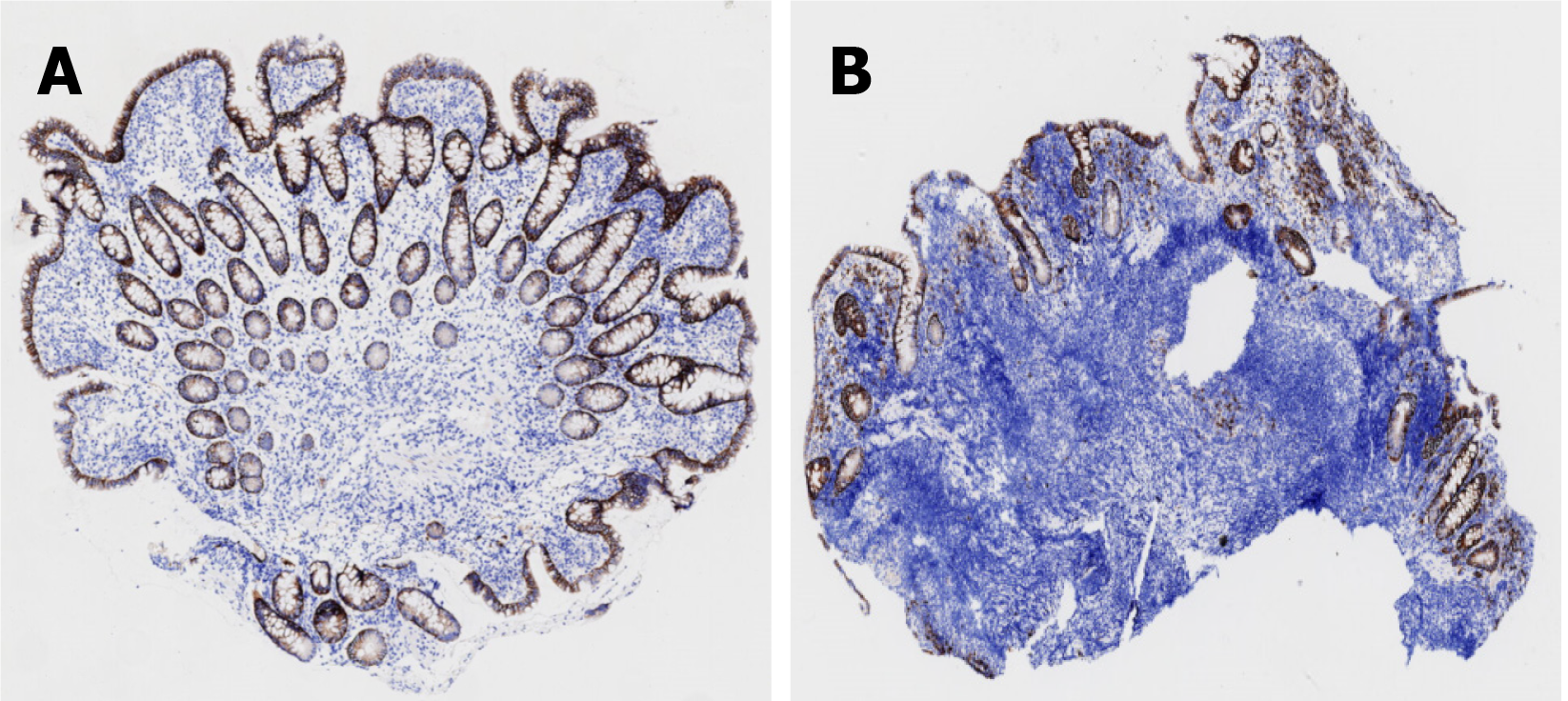

On May 16, gastroscopy revealed a smooth gastric mucosa without bile retention or signs of Helicobacter pylori infection. However, the descending segment of the duodenum had a rough mucosa. Colonoscopy revealed a smooth mucosa in the colon and rectum, without inflammation or masses; however, scattered lymphoid follicular hyperplasia was observed in the distal ileum (Figure 1). Further evaluation of the small intestine using computed tomography showed no abnormalities. Capsule endoscopy revealed polypoid protrusions in the ileum, with increasing density from the oral to anal side. Whole-small bowel DBE revealed rough and swollen mucosa with shrunken villi in the horizontal and descending segments of the duodenum and jejunum, along with segmental longitudinal mucosal swelling with nodular protrusions in the ileum (Figures 2, 3 and 4). Multiple scattered lymphoid follicular hyperplasia were observed on the ileal mucosa. Pathological examination of multiple tissue samples revealed a blunted villous structure, an elongated crypt structure, increased number of intraepithelial lymphocytes, and decreased or absent plasma cells in the lamina propria. Additionally, lymphoid follicular hyperplasia with increased intraepithelial and lamina propria lymphocytes, and focal lymphocyte proliferation were noted in the ileum (Figures 5 and 6). Additional tests for infectious causes, including tuberculosis and viral, parasitic, and fungal infections, were negative. Non-infectious investigations, such as antinuclear antibody profile, anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies, celiac disease (CeD) antibodies, tumor antigen markers, and bone puncture results, were all within normal limits.

After thorough multidisciplinary discussions involving gastroenterology, rheumatology, hematology, pathology, imaging, nutrition, and infection control specialists, the patient was diagnosed with adult CVID-associated enteropathy with hypogammaglobulinemia and hypoalbuminemia. A systematic and comprehensive evaluation revealed low levels of vitamin B12 (< 60 pmol/L) and folic acid (< 5 nmol/L). Genetic tests for the associated genes yielded negative results. Furthermore, investigations indicated the absence of bronchiectasis in the lungs, normal mediastinal lymph node size, and absence of hepatosplenomegaly. Bone marrow aspiration and serum lymphocyte counts were within the normal ranges.

Taking into account the patient’s medical history, the final diagnosis was adult CVID-associated enteropathy, characterized by hypogammaglobulinemia and hypoalbuminemia.

The treatment consisted of intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIg) replacement therapy at a dose of 0.5 g/kg, combined with partial enteral nutrition, folate, mecobalamin, probiotics, and personalized glutamine therapy for mucosal repair. After 5 days of treatment, a follow-up assessment revealed serum globulin level of 20 g/L and a reduction in stool frequency to twice daily with yellow, watery stools. The patient recovered well and was discharged on the fifth day post-operation.

The patient was discharged with a comprehensive follow-up plan aimed at monitoring for non-infectious complications. Follow-up evaluations via telephone consultation at the local hospital in July showed that the patient regularly received IVIg therapy. At present, the patient reports improved abdominal symptoms, with stable stool frequency and weight.

CVID represents a heterogeneous spectrum of primary antibody immunodeficiency disorders characterized by B-cell dysfunction and reduced serum IgG levels. Despite extensive research, the exact pathogenesis of CVID remains unclear. Genetic factors account for only 10%-20% of cases[1,2], and the estimated incidence ranges from 1 in 10000 to 1 in 100000 individuals, affecting all age groups. Clinical presentations are varied, often complicated by recurrent infections, autoimmune phenomena, lymphoproliferative disorders, malignancies, and non-infectious respiratory and gastroin

Non-infectious enteropathy associated with CVID may manifest with duodenal and terminal ileal involvement, presenting endoscopically with mucosal thinning, villous atrophy, congestion, and edema. A hallmark characteristic that aids in diagnosis is the absence of plasma cells in the lamina propria[5]. Recent advancements in understanding immune-mediated gastrointestinal disorders have highlighted the resemblance between non-infectious CVID-associated enteropathy and other autoimmune conditions, such as CeD and inflammatory bowel disease (IBD)[6]. Genetic factors also significantly contribute to the development of CeD-like or IBD-like phenotypes in CVID[7,8]. However, the simultaneous occurrence of CeD and IBD throughout the entire small intestinal mucosa has not been previously reported. Here, we present a case of noninfectious CVID-associated enteropathy with nonspecific clinical manifestations. Diagnostic evaluation, including double-balloon enteroscopy (DBE), facilitated early definitive diagnosis, revealing involvement of the entire small bowel mucosa. Microscopic examination revealed villous atrophy and mucosal swelling reminiscent of CeD, along with segmental mucosal lesions resembling those observed in patients with IBD. Whether these changes represent true CeD and IBD or merely CeD-like and IBD-like alterations remains uncertain. Notably, a previously unreported finding indicated follicular lymphoid tissue proliferation, previously termed nodular lymphoid hyperplasia (NLH)[9], extending throughout the ileum. NLH morphology, akin to certain lymphomas, raises concerns about lymphoma transformation, as evidenced by previous reports associating NLH with lymphoma in immunodeficient populations[10]. These findings underscore the importance of vigilant monitoring and further research to elucidate the clinical significance of early diagnosis and specific treatment of CVID.

Therefore, careful monitoring and management of the lymph nodes are imperative to promptly identify any signs of lymphoma. Given the diverse morphological presentations observed throughout the patient’s small intestinal mucosa, our diagnostic approach emphasized thoroughness. During the DBE, multiple tissue samples were obtained from various sites. Histopathological examination revealed the hallmark absence of plasma cells in the lamina propria, a distinguishing feature that aids in differentiating CVID from other conditions, such as CeD, IBD, and lymphoma.

The primary treatment for CVID typically involves IgG replacement therapy. In this particular case, beyond the fundamental regimen, a comprehensive and personalized approach was adopted. The patient received additional supplements, including vitamin B12, folic acid, enteral nutrition, probiotics, and glutamine to repair the mucous membranes. After discharge, a detailed follow-up plan was implemented. Over the past 7 months, the patient had exhibited improved symptom management and weight stabilization, indicating that timely diagnosis of CVID, coupled with effective follow-up management, can significantly enhance prognosis.

The patient with CVID presented with unexplained diarrhea and protein loss of unknown cause. The atypical clinical symptoms made diagnosis difficult, highlighting the importance of a comprehensive DBE examination covering the entire small intestine. Accordingly, comprehensive DBE in patients with CVID is particularly suitable for patients with small bowel diseases that cannot be diagnosed through routine examinations. Non-infectious enteropathy associated with CVID can affect the entire small intestine, exhibiting phenotypic similarities to CeD and IBD, along with NLH characterized by diverse morphologies. DBE not only facilitates early diagnosis, disease evaluation, and complication moni

| 1. | Wang LA, Abbott JK. "Common variable immunodeficiency: Challenges for diagnosis". J Immunol Methods. 2022;509:113342. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Eskandarian Z, Fliegauf M, Bulashevska A, Proietti M, Hague R, Smulski CR, Schubert D, Warnatz K, Grimbacher B. Assessing the Functional Relevance of Variants in the IKAROS Family Zinc Finger Protein 1 (IKZF1) in a Cohort of Patients With Primary Immunodeficiency. Front Immunol. 2019;10:568. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Agarwal S, Cunningham-Rundles C. Autoimmunity in common variable immunodeficiency. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2019;123:454-460. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 10.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Malesza IJ, Malesza M, Krela-Kaźmierczak I, Zielińska A, Souto EB, Dobrowolska A, Eder P. Primary Humoral Immune Deficiencies: Overlooked Mimickers of Chronic Immune-Mediated Gastrointestinal Diseases in Adults. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Biagi F, Bianchi PI, Zilli A, Marchese A, Luinetti O, Lougaris V, Plebani A, Villanacci V, Corazza GR. The significance of duodenal mucosal atrophy in patients with common variable immunodeficiency: a clinical and histopathologic study. Am J Clin Pathol. 2012;138:185-189. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Agarwal S, Mayer L. Pathogenesis and treatment of gastrointestinal disease in antibody deficiency syndromes. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;124:658-664. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 119] [Cited by in RCA: 106] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Domínguez O, Giner MT, Alsina L, Martín MA, Lozano J, Plaza AM. [Clinical phenotypes associated with selective IgA deficiency: a review of 330 cases and a proposed follow-up protocol]. An Pediatr (Barc). 2012;76:261-267. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Marks DJ, Seymour CR, Sewell GW, Rahman FZ, Smith AM, McCartney SA, Bloom SL. Inflammatory bowel diseases in patients with adaptive and complement immunodeficiency disorders. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2010;16:1984-1992. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Webster AD, Kenwright S, Ballard J, Shiner M, Slavin G, Levi AJ, Loewi G, Asherson GL. Nodular lymphoid hyperplasia of the bowel in primary hypogammaglobulinaemia: study of in vivo and in vitro lymphocyte function. Gut. 1977;18:364-372. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Gompels MM, Hodges E, Lock RJ, Angus B, White H, Larkin A, Chapel HM, Spickett GP, Misbah SA, Smith JL; Associated Study Group. Lymphoproliferative disease in antibody deficiency: a multi-centre study. Clin Exp Immunol. 2003;134:314-320. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |