Published online Mar 16, 2025. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v17.i3.101525

Revised: December 14, 2024

Accepted: February 8, 2025

Published online: March 16, 2025

Processing time: 177 Days and 4.1 Hours

Endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) is a standardized therapeutic approach for early carcinoma of the digestive tracts. In this regard, the process of histopathological diagnosis requires standardization. However, the uneven development of healthcare in China, especially in eastern and western China, creates challenges for sharing a standardized diagnostic process.

To optimize the process of ESD specimen sampling, embedding and slide production, and to provide complete and accurate pathological reports.

We established a practical process of specimen sampling, created standardized reporting templates, and trained pathologists from neighboring hospitals and those in the western region. A training effectiveness survey was conducted, and the collected data were assessed by the corresponding percentages.

A total of 111 valid feedback forms have been received, among which 58% of the participants obtained photographs during specimen collection, whereas the percentage increased to 79% after training. Only 58% and 62% of the respondents ensured the mucosal tissue strips were flat and their order remained unchanged; after training, these two proportions increased to 95% and 92%, respectively. Approximately half the participants measured the depth of the submucosal infiltration, which significantly increased to 95% after training. The percentage of pathologists who did not evaluate lymphovascular invasion effectively reduced. Only 22% of the participants had fixed clinic-pathological meetings before training, which increased to 49% after training. The number of participants who had a thorough understanding of endoscopic diagnosis also significantly increased.

There have been significant improvements in the process of specimen collection, section quality, and pathology reporting in trained hospitals. Therefore, our study provides valuable insights for others facing similar challenges.

Core Tip: The uneven development of healthcare in China creates challenges for sharing a standardized diagnostic process of endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) specimens. Therefore, we established and popularized a standard and practical process of specimen sampling and diagnosis of ESD specimens. The feedback survey revealed significant improvements in the standardized specimen processing and collection, pathological section quality, and pathology report standardization in trained hospitals. Therefore, our study is not only applicable in China, but also in any country performing ESD.

- Citation: Xu C, Chen L, Feng AN, Nie L, Fu Y, Li L, Li W, Sun Q. Establishing and popularizing a standard pathological diagnostic model of endoscopic submucosal dissection specimens in China. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2025; 17(3): 101525

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v17/i3/101525.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v17.i3.101525

For precancerous lesions or early cancers of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, pathological examination plays a crucial role in the therapeutic system of endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD). A standardized and comprehensive pathological diagnosis for ESD specimens, including the histological type and extent of the tumor, depth of infiltration, lympho

First, most pathology departments in China are currently facing an acute shortage of pathological technicians and doctors[4], as evidenced by the lack of pathologists skilled in handling ESD specimens for early cancers of the GI tract, as well as lack of extensive diagnostic experience. The resulting clinical problems include the non-standard processing of ESD specimens and incomplete pathology reports. For example, there is no macroscopic image obtained during specimen sectioning, and the tissue slices are uneven and out of order, making it difficult to accurately describe the size of the lesion and assess the margin of the specimen based on the microscopic observations.

Second, the pathology report lacks details and critical information (e.g., size and gross type of tumor, depth of tumor invasion, etc). Moreover, the lack of standardization and uniformity of pathological diagnostic terminology across regions makes it difficult for endoscopists to understand the true meaning of pathological diagnoses, such as the use of atypical hyperplasia instead of dysplasia/intraepithelial neoplasia to diagnose pre-cancerous lesions of the GI tract[5].

Finally, there is a general lack of communication and cooperation between endoscopists and pathologists. Pathologists are unfamiliar with the endoscopic presentation of early GI cancers. For example, certain pathologists do not understand the rationale for using Lugol's fluid for the endoscopic examination of pre-cancerous lesions and early cancers of the esophagus. In addition, endoscopists may not fully understand the indicators in a pathology report that indicate the risk of metastasis in early cancers of the GI tract. For example, certain endoscopists are unaware of the impact of tumor budding on the risk of lymph node metastasis in early colorectal cancer[6].

To overcome the aforementioned barriers that may affect the treatment and diagnosis of patients with early cancers of the GI tract, we established a standard and practical process for handling pathological specimens based on relevant guidelines and our work experience, and developed a template format for a standardized pathology report. Subse

The procedure for handling ESD specimens is described in our previous study[3]. Given the severe shortage of pathology technicians and their inability to cooperate in high-intensity and high-quality ESD specimen-embedding and slide preparation, we improved the pre-treatment method of ESD specimens for tissue-strip embedding, which we referred to as the "Drum Tower tissue strip processing method". In our method, the pathologist rotates the sectioned tissue strips by 90°, places them in an embedding cassette, and fills them with a thin sponge. The dehydrated tissue strips are then paraffin-embedded and directly sectioned by a pathology technician (Supplementary Figures 1 and 2). This method has proven to be suitable for pathology departments with limited staff and enables the efficient performance of high-quality work.

We developed synoptic ESD pathology reports for the esophagus, stomach, and colorectum, in which the essential elements of tumor assessment should include the following: Tumor location, size, macroscopic type (according to the Paris classification), histological type (based on the WHO classification), degree of differentiation, mode of infiltration (especially for the esophagus), depth of tumor invasion (depth of tumor infiltration of the submucosa should be measured), grade of tumor budding (especially for the colorectum), presence of ulceration, involvement of submucosal structures (e.g., esophageal submucosal glands, ectopic gastric glands, and colorectal lymphoglandular complexes), presence or absence of lymphovascular invasion, and involvement of horizontal and vertical margins of the specimen, etc. (Supplementary material 1). These synoptic report templates help pathologists make a standard and complete diagnosis.

A training program for the endoscopic-pathological diagnosis of early GI cancer was initiated. Since September 2017, we have offered 40 training courses to 145 pathologists from 11 provinces/autonomous regions/municipalities. The training program includes the following: (1) Weekly lectures covering pathological diagnosis of early esophageal, gastric, and colorectal cancer; (2) Weekly endoscopic-pathological case discussions; (3) Practical training of endoscopic specimen sampling and processing; (4) Practical training of case diagnosis; and (5) Training to map and rebuild lesions of early GI cancer on gross photographs and participate in case discussion seminars.

Since December 2021, a training effectiveness survey (feedback form regarding work situation before and after training in training hospitals) has been sent to 145 trainees, involving 33 issues related to specimen collection and reporting standards, as well as endoscopy-pathology cooperation (Supplementary material 2). Thus far, 111 valid feedback forms completed by pathologists from 102 hospitals have been received. The collected data were assessed by the corresponding percentages. All percentages before and after the training were evaluated for statistical significance using a McNemar’s test. Figures were prepared via GraphPad Prism version 6 (GraphPad Software, Inc.).

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the authors’ hospital (No. 2020-254-02). All the procedures in this survey were conducted following the approved guidelines and regulations. All the participants were informed of the purpose of this survey, and this information was given in oral form. Participation was voluntary and onymous.

The survey participants included 80 females and 31 males, among which 54.95% had a Bachelor’s degree, 41.44% had a Master’s degree, and 3.60% had a Doctor of Medicine degree. Most of the participants (67.57%) worked in western China, whereas the remaining (32.43%) were from central China. Most of the participants (81.08%) performed less than 100 cases of ESD diagnosis per year (Table 1).

| Items | Number of pathologists (%) |

| Gender | |

| Female | 80 (72.07) |

| Male | 31 (27.93) |

| Education background | |

| Bachelor | 61 (54.95) |

| Master | 46 (41.44) |

| Doctor of medicine | 4 (3.60) |

| Work seniority (years) | |

| ≤ 5 | 38 (34.23) |

| 5-10 | 19 (17.12) |

| 10-15 | 21 (18.92) |

| 15-20 | 23 (20.72) |

| ≥ 20 | 10 (9.01) |

| Work region | |

| Western China | 75 (67.57) |

| Central China | 36 (32.43) |

| ESD diagnosis (cases/year) | |

| ≤ 100 | 90 (81.08) |

| 100-300 | 10 (9.01) |

| 300-500 | 6 (5.41) |

| ≥ 500 | 5 (4.50) |

| Total | 111 (100) |

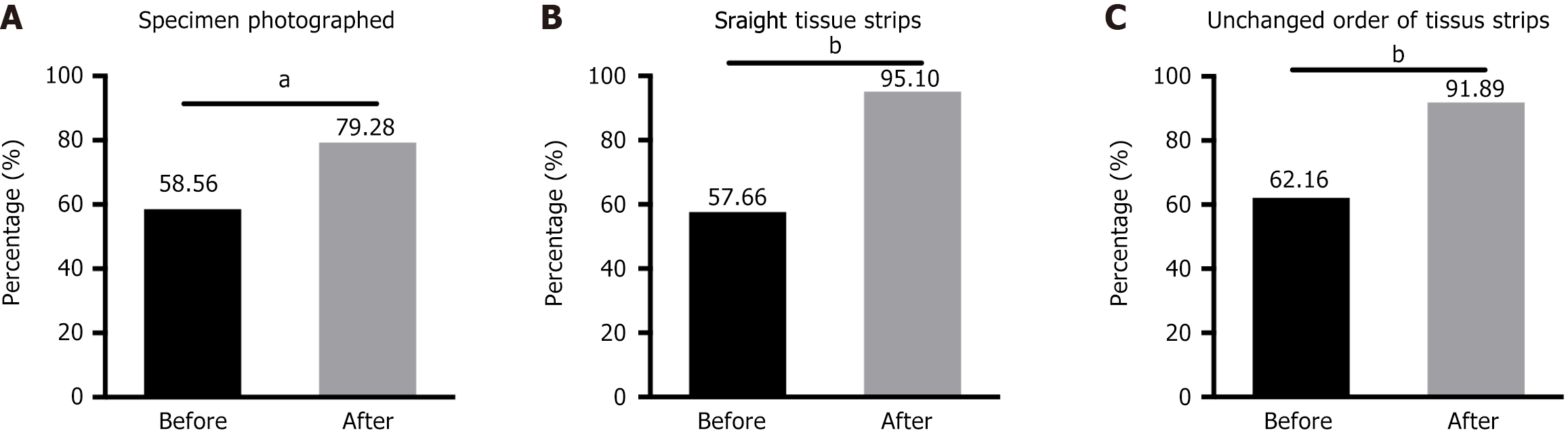

To assess whether ESD specimen collection is standardized, several aspects of the collection process must be noted: Whether gross photographs of the specimen are obtained, and whether it is possible to ensure that the mucosal tissue strips are flat and in the correct order. Among the 111 pathologists who participated in the questionnaire survey, the percentages of trainees who obtained gross photographs during specimen collection before and after training were 58.56% and 79.28%, respectively (Figure 1A).

Tissue embedding is a critical step in producing high-quality slides for accurate diagnosis. Poor orientation of tissue sections may result in loss of superficial tumor tissue or deep submucosal tissue due to wax block trimming, as well as loss of the basal margin of the specimen. Thus, to optimize this process, all tissue slices should be embedded ‘en face’ or on the edge. Optimally, the slices are also sequentially laid in the cassette. However, we found that only 57.66% and 62.16% of the survey respondents were able to ensure that the mucosal tissue strips were flat and that the order of the tissue strips remained unchanged during the specimen collection process before training; after training, these two proportions increased to 95.50% and 91.89%, respectively (Figure 1B and C). Thus, to a certain extent, our training standardizes the handling of specimens by pathologists and the preparation of slides by technicians.

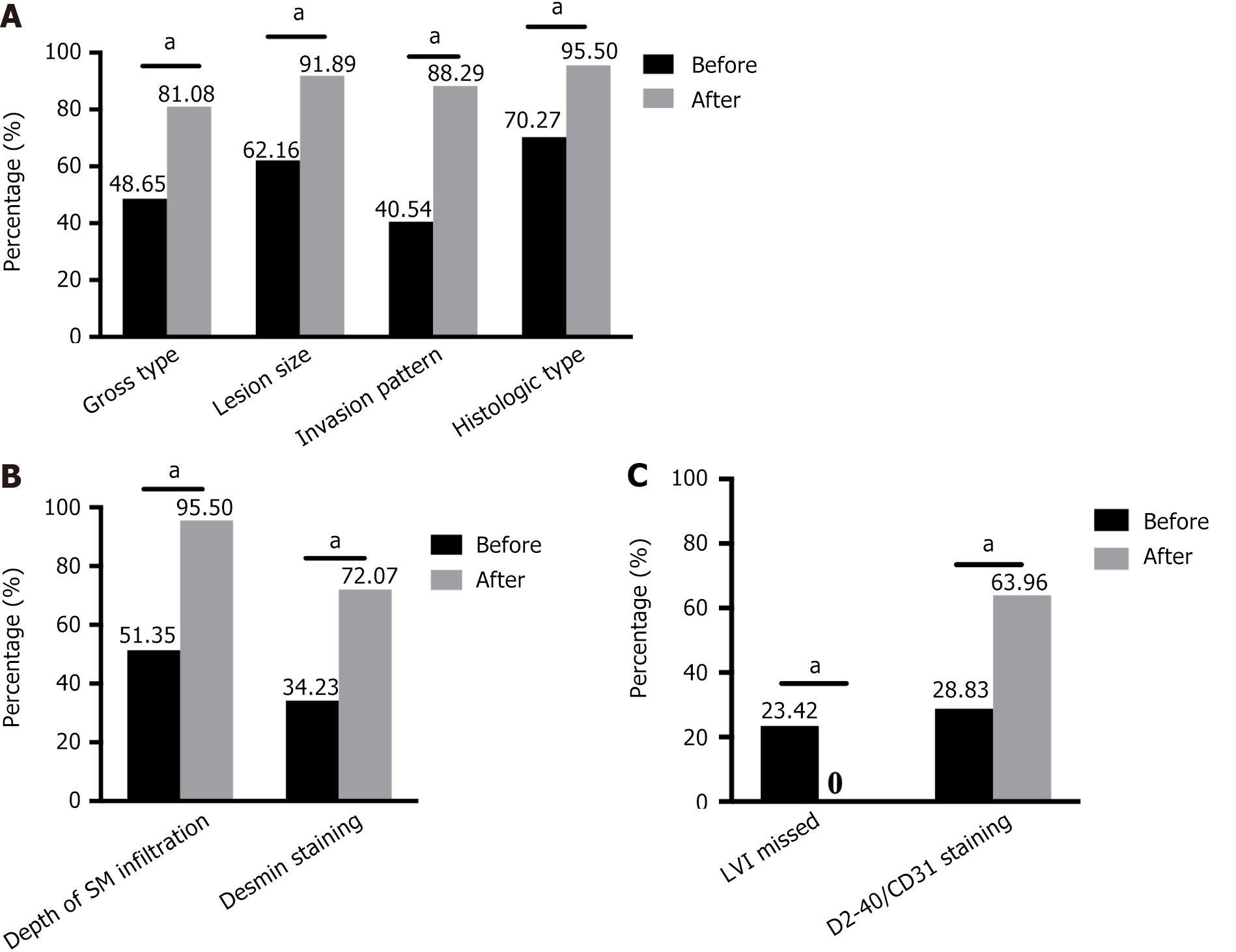

A complete pathology report of early GI cancers contains both the gross description and histological features of the tumor. Our survey revealed that before training, only a few trainees recorded the gross type of tumor (48.65%), size of the lesion (62.16%), pattern of invasion (40.54%), and histological type (70.27%) in their pathology reports; however, after training, these proportions increased to 81.08%, 91.89%, 88.29%, and 95.50%, respectively (Figure 2A).

Tumor infiltration into the submucosal layer is strongly associated with lymph node metastasis and patient prognosis[7]. Histological evaluation of ESD samples requires measuring the infiltration depth of cancers with submucosal invasion. However, our survey revealed that only half (51.35%) of the pathologists measured the depth of submucosal infiltration before training, whereas after training, this proportion significantly increased to 95.50%. In addition, the presence of submucosal infiltration is often confirmed by anti-Desmin immunohistochemical (IHC) staining to observe muscularis mucosae destruction. After training, the majority of the participants (80/111) routinely performed anti-Desmin IHC staining to assist in diagnoses, compared to only a few (38/111) before the training (Figure 2B).

Lymphovascular invasion is another independent prognostic factor[8,9]. According to relevant guidelines from Europe[10], North America[11], Japan[12-14], and China[15,16], cancer invasion of the lymphatic and blood vessels (including capillaries in the mucosal layer and veins in the submucosal layer) must be reported. However, our questionnaire revealed that 23.42% of the pathologists did not assess vascular invasion in their diagnostic reports before training, which decreased to 0% after training. Moreover, the number of trainees who adopted IHC staining for CD31 and D2-40 to identify lymphovascular invasion doubled (28.83% before training vs 63.96% after training; Figure 2C).

In addition, our survey revealed that almost all the participants correctly report the degree of tumor differentiation and the status of the resection margins (Supplementary Figure 3). Few studies have investigated the mucin phenotypes of gastric cancer (14.41%) and conducted corresponding IHC staining (9.91%); after training, the percentages increased to 61.26% and 34.23%, respectively (Supplementary Figure 4).

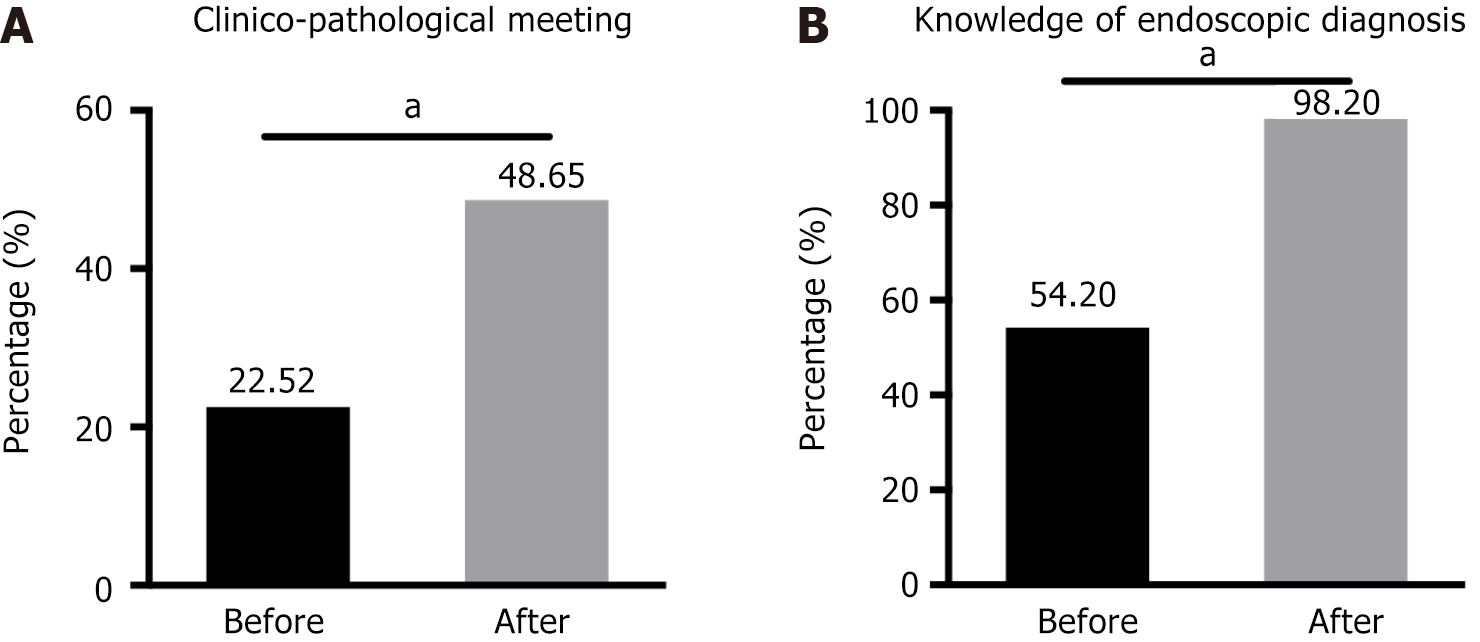

Although most trainees (82.88%) believed that endoscopic-pathological case discussions were beneficial for improving the diagnostic skills of pathologists, only 22.52% of the participants arranged regular endoscopic-pathological seminars in their hospitals before the training; after training, this percentage increased to 48.65% (Figure 3A). As shown in Figure 3B, only approximately half of the participants were aware of the endoscopic terminology and manifestations of early GI cancers and regularly communicated with endoscopists. Our training effectively increased this ratio to 98.20%.

Currently, endoscopic resection (ER), including endoscopic mucosal resection and ESD, has become the standard treatment of choice for the treatment of precancerous lesions and a portion of early-stage cancers without risk of lymph node metastasis of GI tract, especially in Asian countries, such as Japan[12,14,17], Korea[18,19] and China[15,20,21]. The use of standardized protocols by pathologists for handling, grossing, and evaluation of ESD specimens after ER is essential to provide a consistent and accurate diagnosis for both the patient and endoscopist.

However, due to the shortage of pathologists and technicians[4], especially those who are experienced in processing and diagnosing ESD specimens, we created a feasible sample-handling procedure and synoptic report templates to ensure the accuracy and completeness of pathology reports. In addition, considering that healthcare in certain areas is relatively underdeveloped[22], a training course regarding the endoscopic-pathological diagnosis of early GI cancer has been conducted regularly since 2017. To test the effectiveness of the training, we also conducted follow-up questionnaires for the trainees.

As demonstrated by the questionnaire results, our proposed method of processing tissue strips of ESD specimens improved the quality of specimen-handling by the trained pathologists. The results demonstrated that after training, most of the trainees were able to ensure that the paraffin-embedded tissue strips were flat and in order. Compared with the ESD specimen-handling process recommended in Japan, our “Drum Tower tissue strip processing method”, in which the pathologist turns the tissue strips by 90° in sequence after the specimen has been cut, allows the technician to rapidly paraffin-embed the tissue strips after dehydration, reduces the work intensity of the technician in terms of the process, thus alleviating the general lack of technicians in primary hospitals, and enables rapid and high-quality ESD specimen-processing despite the scarcity of technicians.

A standard pathology report of an ESD specimen provides clinicians with a full picture of the lesion, including gross manifestations, histologic features and especially key points related to the patient prognosis. For example, the depth of tumor invasion[8], degree of tumor differentiation[9], lymphovascular invasion[7-9], and grade of tumor budding[23] are associated with the risk of lymph-node metastasis. To avoid the local recurrence of the tumor, complete resection with negative margins is essential[24]. To varying degrees, the pre-training questionnaires revealed that the ESD pathology reports from the participating hospitals lacked an assessment of the gross type, histological type, lesion size, pattern of infiltration, depth of invasion, and lymphovascular invasion of the tumor. All these pathology reporting deficiencies improved after the training. The results demonstrate that the participants were unaware of or unfamiliar with the norms of the pathological assessment of ESD specimens for early GI cancer; furthermore, the results highlight the advantages of a synoptic pathology report, that is, it can be used as a mandatory reminder for the pathologist to assess the lesion comprehensively[25].

Accurate pathological diagnosis of early GI cancers requires closer interdisciplinary collaboration between pathologists and GI endoscopists. Our questionnaire revealed a lack of communication between pathologists and endoscopists in the hospitals involved in the training. Furthermore, there is no significant difference in the occurrence of such problems among hospitals of different levels or in different regions, which indicates that this is a widespread problem. Although 48.65% of the hospitals conducted regular case discussions between pathologists and endoscopists after training, regular communication between pathologists and endoscopists was lacking in more than half of the hospitals. Our training can only increase the awareness of pathologists in communicating with clinicians; however, to better address the lack of communication between pathologists and clinicians, it may be necessary to further increase the number of staff in the pathology departments of primary hospitals[4,22].

Overall, our improved tissue-strip processing method and synoptic report templates have helped us make standardized, accurate, and complete pathological diagnoses for patients with early GI cancer. The ongoing training and follow-up questionnaires we conducted since 2017 have not only standardized the processing of ESD specimens, but also improved the quality of pathological slides and reports in trained hospitals.

We sincerely thank all the survey participants for their cooperation, and we thank Dr. Yi-Cheng Sun for his kind help during our chart-making process.

| 1. | Pimentel-Nunes P, Libânio D, Bastiaansen BAJ, Bhandari P, Bisschops R, Bourke MJ, Esposito G, Lemmers A, Maselli R, Messmann H, Pech O, Pioche M, Vieth M, Weusten BLAM, van Hooft JE, Deprez PH, Dinis-Ribeiro M. Endoscopic submucosal dissection for superficial gastrointestinal lesions: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Guideline - Update 2022. Endoscopy. 2022;54:591-622. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 410] [Cited by in RCA: 360] [Article Influence: 120.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Nagata K, Shimizu M. Pathological evaluation of gastrointestinal endoscopic submucosal dissection materials based on Japanese guidelines. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;4:489-499. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Sun Q, Huang Q. Pathologic Evaluation of Endoscopic Resection Specimens. In: Huang, Q, editors. Gastric Cardiac Cancer. Cham: Springer, 2018. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 4. | Chinese Society of Pathology. [Investigation and consideration on the status of pathology departments in 3 831 hospitals of 31 provinces, municipalities and autonomous regions]. Zhonghua Bing Li Xue Za Zhi. 2020;49:1217-1220. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Chen GY, Huang SF. [Interpretation of the fifth edition of World Health Organization classification of tumors of the digestive system: selected topic on early gastric cancer]. Zhonghua Bing Li Xue Za Zhi. 2020;49:882-885. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Lugli A, Kirsch R, Ajioka Y, Bosman F, Cathomas G, Dawson H, El Zimaity H, Fléjou JF, Hansen TP, Hartmann A, Kakar S, Langner C, Nagtegaal I, Puppa G, Riddell R, Ristimäki A, Sheahan K, Smyrk T, Sugihara K, Terris B, Ueno H, Vieth M, Zlobec I, Quirke P. Recommendations for reporting tumor budding in colorectal cancer based on the International Tumor Budding Consensus Conference (ITBCC) 2016. Mod Pathol. 2017;30:1299-1311. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 575] [Cited by in RCA: 730] [Article Influence: 91.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Zhao X, Cai A, Xi H, Chen L, Peng Z, Li P, Liu N, Cui J, Li H. Predictive Factors for Lymph Node Metastasis in Undifferentiated Early Gastric Cancer: a Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. J Gastrointest Surg. 2017;21:700-711. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Ebbehøj AL, Jørgensen LN, Krarup PM, Smith HG. Histopathological risk factors for lymph node metastases in T1 colorectal cancer: meta-analysis. Br J Surg. 2021;108:769-776. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Kwee RM, Kwee TC. Predicting lymph node status in early gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer. 2008;11:134-148. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 114] [Cited by in RCA: 129] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Labianca R, Nordlinger B, Beretta GD, Mosconi S, Mandalà M, Cervantes A, Arnold D; ESMO Guidelines Working Group. Early colon cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2013;24 Suppl 6:vi64-vi72. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 563] [Cited by in RCA: 650] [Article Influence: 59.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Draganov PV, Wang AY, Othman MO, Fukami N. AGA Institute Clinical Practice Update: Endoscopic Submucosal Dissection in the United States. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;17:16-25.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 214] [Cited by in RCA: 321] [Article Influence: 53.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Ishihara R, Arima M, Iizuka T, Oyama T, Katada C, Kato M, Goda K, Goto O, Tanaka K, Yano T, Yoshinaga S, Muto M, Kawakubo H, Fujishiro M, Yoshida M, Fujimoto K, Tajiri H, Inoue H; Japan Gastroenterological Endoscopy Society Guidelines Committee of ESD/EMR for Esophageal Cancer. Endoscopic submucosal dissection/endoscopic mucosal resection guidelines for esophageal cancer. Dig Endosc. 2020;32:452-493. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 127] [Cited by in RCA: 262] [Article Influence: 52.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Ono H, Yao K, Fujishiro M, Oda I, Uedo N, Nimura S, Yahagi N, Iishi H, Oka M, Ajioka Y, Fujimoto K. Guidelines for endoscopic submucosal dissection and endoscopic mucosal resection for early gastric cancer (second edition). Dig Endosc. 2021;33:4-20. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 137] [Cited by in RCA: 308] [Article Influence: 77.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Tanaka S, Kashida H, Saito Y, Yahagi N, Yamano H, Saito S, Hisabe T, Yao T, Watanabe M, Yoshida M, Saitoh Y, Tsuruta O, Sugihara KI, Igarashi M, Toyonaga T, Ajioka Y, Kusunoki M, Koike K, Fujimoto K, Tajiri H. Japan Gastroenterological Endoscopy Society guidelines for colorectal endoscopic submucosal dissection/endoscopic mucosal resection. Dig Endosc. 2020;32:219-239. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 138] [Cited by in RCA: 273] [Article Influence: 54.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Early Diagnosis and Treatment Group of the Chinese Medical Association Oncology Branch. [Chinese expert consensus on early diagnosis and treatment of esophageal cancer]. Zhonghua Zhong Liu Za Zhi. 2022;44:1066-1075. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | National Cancer Center, China; Expert Group of the Development of China Guideline for the Screening; Early Detection and Early Treatment of Colorectal Cancer. [China guideline for the screening, early detection and early treatment of colorectal cancer (2020, Beijing)]. Zhonghua Zhong Liu Za Zhi. 2021;43:16-38. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Japanese Gastric Cancer Association. Japanese Gastric Cancer Treatment Guidelines 2021 (6th edition). Gastric Cancer. 2023;26:1-25. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 199] [Cited by in RCA: 609] [Article Influence: 304.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 18. | Kim TH, Kim IH, Kang SJ, Choi M, Kim BH, Eom BW, Kim BJ, Min BH, Choi CI, Shin CM, Tae CH, Gong CS, Kim DJ, Cho AE, Gong EJ, Song GJ, Im HS, Ahn HS, Lim H, Kim HD, Kim JJ, Yu JI, Lee JW, Park JY, Kim JH, Song KD, Jung M, Jung MR, Son SY, Park SH, Kim SJ, Lee SH, Kim TY, Bae WK, Koom WS, Jee Y, Kim YM, Kwak Y, Park YS, Han HS, Nam SY, Kong SH; Development Working Groups for the Korean Practice Guidelines for Gastric Cancer 2022 Task Force Team. Korean Practice Guidelines for Gastric Cancer 2022: An Evidence-based, Multidisciplinary Approach. J Gastric Cancer. 2023;23:3-106. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 107] [Cited by in RCA: 158] [Article Influence: 79.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Park CH, Yang DH, Kim JW, Kim JH, Kim JH, Min YW, Lee SH, Bae JH, Chung H, Choi KD, Park JC, Lee H, Kwak MS, Kim B, Lee HJ, Lee HS, Choi M, Park DA, Lee JY, Byeon JS, Park CG, Cho JY, Lee ST, Chun HJ. [Clinical Practice Guideline for Endoscopic Resection of Early Gastrointestinal Cancer]. Korean J Gastroenterol. 2020;75:264-291. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Wang FH, Zhang XT, Li YF, Tang L, Qu XJ, Ying JE, Zhang J, Sun LY, Lin RB, Qiu H, Wang C, Qiu MZ, Cai MY, Wu Q, Liu H, Guan WL, Zhou AP, Zhang YJ, Liu TS, Bi F, Yuan XL, Rao SX, Xin Y, Sheng WQ, Xu HM, Li GX, Ji JF, Zhou ZW, Liang H, Zhang YQ, Jin J, Shen L, Li J, Xu RH. The Chinese Society of Clinical Oncology (CSCO): Clinical guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of gastric cancer, 2021. Cancer Commun (Lond). 2021;41:747-795. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 378] [Cited by in RCA: 463] [Article Influence: 115.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 21. | Fang JY, Zheng S, Jiang B, Lai MD, Fang DC, Han Y, Sheng QJ, Li JN, Chen YX, Gao QY. Consensus on the Prevention, Screening, Early Diagnosis and Treatment of Colorectal Tumors in China: Chinese Society of Gastroenterology, October 14-15, 2011, Shanghai, China. Gastrointest Tumors. 2014;1:53-75. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 22. | Wang Z, He H, Liu X, Wei H, Feng Q, Wei B. Health resource allocation in Western China from 2014 to 2018. Arch Public Health. 2023;81:30. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Cappellesso R, Luchini C, Veronese N, Lo Mele M, Rosa-Rizzotto E, Guido E, De Lazzari F, Pilati P, Farinati F, Realdon S, Solmi M, Fassan M, Rugge M. Tumor budding as a risk factor for nodal metastasis in pT1 colorectal cancers: a meta-analysis. Hum Pathol. 2017;65:62-70. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 9.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Rotermund C, Djinbachian R, Taghiakbari M, Enderle MD, Eickhoff A, von Renteln D. Recurrence rates after endoscopic resection of large colorectal polyps: A systematic review and meta-analysis. World J Gastroenterol. 2022;28:4007-4018. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 25. | Hewer E, Rump A, Langer R. [Standardized structured reports for gastrointestinal tumors]. Pathologe. 2022;43:57-62. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |