Published online Feb 16, 2025. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v17.i2.100556

Revised: December 31, 2024

Accepted: January 21, 2025

Published online: February 16, 2025

Processing time: 177 Days and 7.1 Hours

In this letter we comment on the article by Zhang et al published in the recent issue of the World Journal of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy 2024. We focus specifically on the management of gastric varices (GV), which is a significant consequence of portal hypertension, is currently advised to include beta-blocker therapy for primary prophylaxis and transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt for secondary prophylaxis or active bleeding. Although it has been studied, direct endoscopic injection of cyanoacrylate glue has limitations, such as the inability to fully characterize GV endoscopically and the potential for distant glue embolism. In order to achieve this, endoscopic ultrasound has been used to support GV characterization, real-time therapy imaging, and Doppler obliteration verification.

Core Tip: The primary treatment for isolated gastric varices (IGVs), which have the potential to be harmful, is endoscopic. Treatment guided by endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) is more accurate than traditional endoscopic therapy. In this situation, EUS-guided coil embolization in combination with cyanoacrylate injection proved to be an effective treatment method for an IGV entangled with an artery. This was a successful treatment for an IGV that was entangled in an artery.

- Citation: Amalou K, Rekab R, Belloula A, Saidani K. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided treatment of isolated gastric varices. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2025; 17(2): 100556

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v17/i2/100556.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v17.i2.100556

Among patients with portal hypertension, 20% have gastric varices (GV)[1]. Mainly due to portal system obstruction and various forms of liver cirrhosis. GV bleeding is less frequent than esophageal variceal (EV) bleeding but is more severe with higher mortality and a higher risk of rebleeding. Increased portal vein pressure, hepatic vein wedge pressure-free hepatic vein pressure (HVPG) causes the development of GVs[2].

The three most widely used classifications for GV are the Hashizome, Arkawa's, and Sarin classifications.

Based on its position in the stomach and its interaction with EV, the Sarin classification divides GV into two different kinds: Gastroesophageal varices (GOV) and isolated GVs (IGV). While GOV2 are EV extending into the fundus, GOV1 are EV extending into the lesser curvature. Whereas IGV2 are isolated varices in other parts of the stomach, IGV1 are isolated fundal varices[3]. The most prevalent variant, known as GOV1, also called junctional varices, is treated similarly to EV[3]. Known as cardiofundal varices, GOV2 and IGV1 are more difficult to control when they bleed and have a higher risk of mortality and recurrence than GOV1[3]. IGV2 are rare, especially in cases with cirrhosis[4].

The location (IGV1 > GOV2 > GOV1), varices > 5 mm in size, HVPG > 12 mmHg, decompensated cirrhosis (Child B or C), and the endoscopic presence of red wale markings are the most significant predictors of bleeding[5]. This rate is influenced by the center's ability to provide highly specialized care and treatment alternatives in addition to the degree of variceal growth.

Compared to EV, the evidence for the current management recommendations for GV is less compelling. Most people agree that GOV1 ought to be managed as an EV[1]. Less is known about how to treat cardiofundal varices, though. The authors of the 2016 American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) guidelines divided the management of GOV2/IGV1 into three groups: Acute treatment, secondary prophylaxis of GV hemorrhage, and primary prophylaxis. The AASLD advises non-selective beta-blockers for primary prophylaxis[1]. In addition to regular medical care, transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunting (TIPS) is advised for acute hemorrhage. TIPS, or balloon-occluded retrograde transvenous obliteration (BRTO), is the primary line of treatment for secondary prophylaxis[1]. Unlike TIPS, which redirects blood flow, BRTO raises portal pressures but needs the presence of a gastrorenal shunt[5,6]. Because of this, some recommend using TIPS rather than BRTO if the hepatic venous portal gradient is more than 12 mmHg[1].

TIPS and BRTO have limits, even though they are advised for GV. TIPS may become more complex due to encephalopathy[7] and rebleeding caused by shunt malfunction[8]. Ascites may worsen and portal pressure may rise with BRTO[8]. Direct endoscopic injection (DEI) of tissue adhesives into GV has been suggested as a replacement to TIPS/BRTO. The first account of this was provided in a 1986 case report by Soehendra et al[8], in which the authors used cyanoacrylate (CYA) adhesive to conduct DEI on a patient who had stomach varices and had previously experienced haemorrhage[9]. There was no more bleeding after receiving endoscopic therapy[9].

Despite the relative safety of DEI-CYA, the most expected consequence is distal embolization, which is brought on by glue flowing downstream prior to polymerization. Up to 5% of DEI-CYA cases are thought to result in pulmonary embolism, and reports of splenic infarction, portal vein embolization, septic emboli, stroke, and coronary emboli have also been made[10]. Fever and momentary abdominal ache are two further side effects of DEI-CYA[11]. There have also been reports of instrument damage brought on by adhesion to the scope tip and polymerization of CYA in the working channel[12].

Although DEI with CYA shows potential, there are a number of limitations. Crucially, it might be challenging to diagnose stomach varices with a routine upper endoscopy, especially when there is active bleeding[13]. Moreover, it is not always simple to assess the size and existence of feeding vessels. This is especially important because varix size and the existence of para-gastric veins are risk factors for GV rebleeding[14]. Because it can more clearly view the stomach wall and related vasculature even in the presence of an active bleed, endoscopy ultrasonography (EUS) may therefore be advantageous in the management of GV[15].

The fact that traditional endoscopy's assessment of variceal obliteration is subjective and dependent on measuring the varix's "hardening" after injection presents another possible limitation of DEI-CYA[16]. This is especially crucial because the quantity of CYA administered raises the possibility of an embolization that might be lethal[17]. Reducing the volume of glue injected can be accomplished by employing a more accurate method of mining obliteration.

Although EUS can be helpful as a supplemental diagnostic tool, its therapeutic application has come to light only recently. Various hemostatic adhesives and devices, such as CYA (EUS-CYA), coils (EUS-coil), coils with CYA (EUS-coil/CYA), thrombin (EUS-thrombin), and coils with absorbable gelatin sponge (EUS-coil/AGS), can be injected into GV under EUS control.

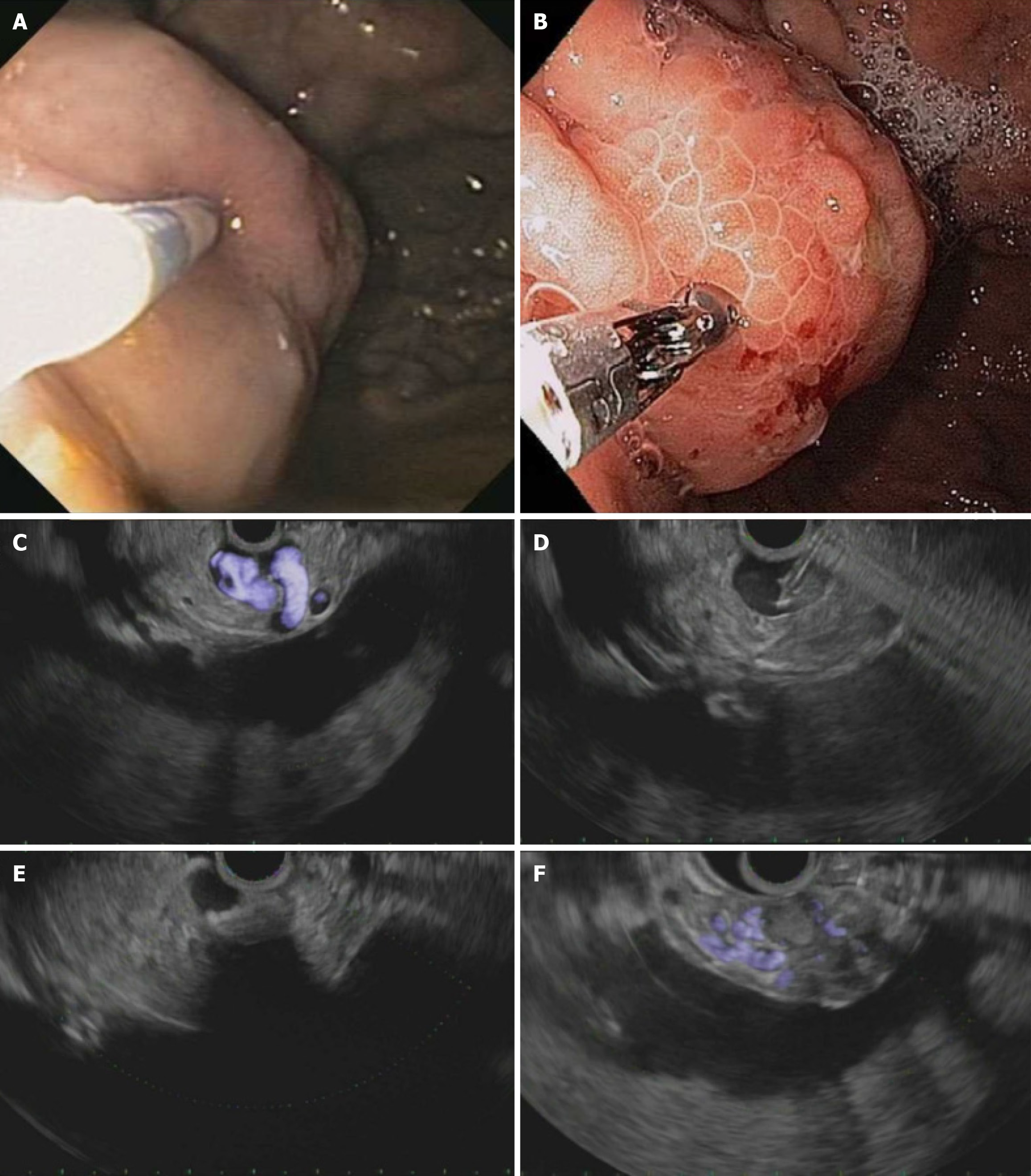

Romero-Castro et al[16] published the first description of EUS-guided CYA injection. During the mean 10-month follow-up, there were no complications or recurrent hemorrhage indicating the effectiveness of EUS-CYA[17,18]. This method has been detailed by others since this study. The precise procedure for carrying out EUS-CYA is not widely agreed upon. The varix itself is the injection target, and a linear array echoendoscope is usually used[19,20]. To enable real-time injection and GV obliteration visualization, either a 19 g[20-22] or a 22 g[22] needle is utilized to administer CYA. EUS color Doppler and fluoroscopy are also employed during the procedure (Figure 1).

For the purposes of primary prophylaxis, acute GV hemorrhage, and secondary prophylaxis of GV, EUS-CYA has been reported. The profile of negative effects for EUS-CYA and DEI-CYA is comparable. Of the patients performing EUS-CYA, 8%–15%[21,22] experienced abdominal pain, 8%–9%[22] developed fever, and 2%–6%[19,22] reported temporary bacteremia. In 3% of patients having this procedure performed, an injection site ulcer was observed[19]. Not only does systemic embolization occur even under EUS supervision. Nine out of the 19 patients (47%) who had EUS-CYA had pulmonary embolism, according to Romero-Castro et al[17]; these patients had no symptoms and the pulmonary embolism was found during routine imaging performed as part of the study protocol[18]. In other investigations, 2%–6% of patients had pulmonary emboli and 2%–6% had splenic infarcts[22,23].

EUS-CYA carries the same distal embolization incidence as DEI-CYA. Because of this, the use of EUS-guided coil injection has been investigated, either in conjunction with or independently of CYA injection, in the hopes that the coil will be able to offer primary hemostasis, act as a scaffold to hold glue inside the varix, and decrease the risk of embolization[24].

Applying a coil to the GV lumen could be a novel extra approach. Since Levy et al's initial use of coils to treat ectopic varices[23], this method has become more widely employed in medical care. Embolization is an issue associated with CYA injection monotherapy[1]. The synthetic fibers in the coil serve as CYA's guidance, decreasing the danger of embolism. In addition, fibers have the function of slowing blood flow through the vessel while stimulating the production of blood clots, which block the vessel[1]. Thus, the idea of using an intravascular coil as a novel treatment for stomach varices was explored.

Romero-Castro et al[24] initially reported coil injection in GV in 2010. For a transesophageal method[24-26] or a transgastric approach[27,28] for coil injection, the echoendoscope is either placed in the distal esophagus. The varix or a feeding vessel is the target when using a 19 g[13,15,16,27,28] or 22 g[29] needle. With the stylet acting as a pusher, coils with a diameter ranging from 5 to 20 mm[13,16,27,28,29] are inserted into the varix via a FNA needle. Using the same needle, CYA is injected right away following coil deployment if glue injection is needed[24]. A Color Doppler test is used to verify if there is no flow inside the varix.

There are limited data examining coil injection alone. Some groups suggest using both coil and glue injection instead of only coil injection, believing that the two modalities will work in concert to minimize distal embolization and stop bleeding. A comprehensive case study of 151 GV patients who remained successful EUS-coil/CYA was published by Bhat et al[28]. Of them, 125 underwent clinical or endoscopic/EUS follow-up. Twenty patients (16%) experienced bleeding after treatment that was either early (n = 12) or late (n = 8). Out of 100 patients who underwent follow-up EUS, 73 underwent successful obliteration in just one treatment, 14 needed subsequent procedures, 3 were unable to undergo obliteration, and 4 underwent initial obliteration with persistent varices found during follow-up.

The use of EUS guidance in the treatment of GV is a new approach that could greatly improve how we manage this medical condition. Even in the presence of active bleeding, EUS guidance allows for clear visualization and accurate targeting of the GV and feeding vessels, something that is not always feasible during traditional endoscopy. Additionally, the superior imaging of varices reduces the quantity of therapeutic drugs required to achieve obliteration, perhaps mitigating related side effects. Furthermore, EUS-guided injection of particular arteries is not linked to large increases in portal hypertension that result in ascites or shunting that results in hepatic encephalopathy, in contrast to angiographic techniques as BRTO or TIPS. Future research is required to prove that EUS-guided GV therapy is superior to traditional medicinal and radiologic therapies, even if these prospective benefits are encouraging[29].

| 1. | Garcia-Tsao G, Abraldes JG, Berzigotti A, Bosch J. Portal hypertensive bleeding in cirrhosis: Risk stratification, diagnosis, and management: 2016 practice guidance by the American Association for the study of liver diseases. Hepatology. 2017;65:310-335. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1108] [Cited by in RCA: 1435] [Article Influence: 179.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 2. | European Association for the Study of the Liver. Corrigendum to "EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines for the management of patients with decompensated cirrhosis" [J Hepatol 69 (2018) 406-460]. J Hepatol. 2018;69:1207. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 178] [Cited by in RCA: 138] [Article Influence: 19.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Wani ZA, Bhat RA, Bhadoria AS, Maiwall R, Choudhury A. Gastric varices: Classification, endoscopic and ultrasonographic management. J Res Med Sci. 2015;20:1200-1207. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Boregowda U, Umapathy C, Halim N, Desai M, Nanjappa A, Arekapudi S, Theethira T, Wong H, Roytman M, Saligram S. Update on the management of gastrointestinal varices. World J Gastrointest Pharmacol Ther. 2019;10:1-21. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (12)] |

| 5. | North Italian Endoscopic Club for the Study and Treatment of Esophageal Varices. Prediction of the first variceal hemorrhage in patients with cirrhosis of the liver and esophageal varices. A prospective multicenter study. N Engl J Med. 1988;319:983-989. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 996] [Cited by in RCA: 841] [Article Influence: 22.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 6. | Suhocki PV, Lungren MP, Kapoor B, Kim CY. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt complications: prevention and management. Semin Intervent Radiol. 2015;32:123-132. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 9.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Al-Osaimi AM, Sabri SS, Caldwell SH. Balloon-occluded Retrograde Transvenous Obliteration (BRTO): Preprocedural Evaluation and Imaging. Semin Intervent Radiol. 2011;28:288-295. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Soehendra N, Nam VC, Grimm H, Kempeneers I. Endoscopic obliteration of large esophagogastric varices with bucrylate. Endoscopy. 1986;18:25-26. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 179] [Cited by in RCA: 167] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Martins FP, Macedo EP, Paulo GA, Nakao FS, Ardengh JC, Ferrari AP. Endoscopic follow-up of cyanoacrylate obliteration of gastric varices. Arq Gastroenterol. 2009;46:81-84. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Guo YW, Miao HB, Wen ZF, Xuan JY, Zhou HX. Procedure-related complications in gastric variceal obturation with tissue glue. World J Gastroenterol. 2017;23:7746-7755. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 11. | Mazzawi T, Markhus CE, Havre RF, Do-Cong Pham K. EUS-guided coil placement for acute gastric variceal bleeding induced by non-EUS-guided variceal glue injection (with video). Endosc Int Open. 2019;7:E380-E383. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Ma L, Tseng Y, Luo T, Wang J, Lian J, Tan Q, Li F, Chen S. Risk stratification for secondary prophylaxis of gastric varices due to portal hypertension. Dig Liver Dis. 2019;51:1678-1684. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Wang X, Yu S, Chen X, Duan L. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided injection of coils and cyanoacrylate glue for the treatment of gastric fundal varices with abnormal shunts: a series of case reports. J Int Med Res. 2019;47:1802-1809. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Lôbo MRA, Chaves DM, DE Moura DTH, Ribeiro IB, Ikari E, DE Moura EGH. Safety and efficacy of the EUS guide coil plus cyanoacrylate versus the conventional cyanoacrylate technique in the treatment of gastric varices: a randomized controlled trial. Arq Gastroenterol. 2019;56:99-105. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 8.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Michael PG, Antoniades G, Staicu A, Seedat S. Pulmonary Glue Embolism: An unusual complication following endoscopic sclerotherapy for gastric varices. Sultan Qaboos Univ Med J. 2018;18:e231-e235. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Romero-Castro R, Pellicer-Bautista FJ, Jimenez-Saenz M, Marcos-Sanchez F, Caunedo-Alvarez A, Ortiz-Moyano C, Gomez-Parra M, Herrerias-Gutierrez JM. EUS-guided injection of cyanoacrylate in perforating feeding veins in gastric varices: results in 5 cases. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;66:402-407. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 126] [Cited by in RCA: 127] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Romero-Castro R, Ellrichmann M, Ortiz-Moyano C, Subtil-Inigo JC, Junquera-Florez F, Gornals JB, Repiso-Ortega A, Vila-Costas J, Marcos-Sanchez F, Muñoz-Navas M, Romero-Gomez M, Brullet-Benedi E, Romero-Vazquez J, Caunedo-Alvarez A, Pellicer-Bautista F, Herrerias-Gutierrez JM, Fritscher-Ravens A. EUS-guided coil versus cyanoacrylate therapy for the treatment of gastric varices: a multicenter study (with videos). Gastrointest Endosc. 2013;78:711-721. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 138] [Cited by in RCA: 156] [Article Influence: 13.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Gonzalez JM, Giacino C, Pioche M, Vanbiervliet G, Brardjanian S, Ah-Soune P, Vitton V, Grimaud JC, Barthet M. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided vascular therapy: is it safe and effective? Endoscopy. 2012;44:539-542. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Tang RS, Teoh AY, Lau JY. EUS-guided cyanoacrylate injection for treatment of endoscopically obscured bleeding gastric varices. Gastrointest Endosc. 2016;83:1032-1033. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Bick BL, Al-Haddad M, Liangpunsakul S, Ghabril MS, DeWitt JM. EUS-guided fine needle injection is superior to direct endoscopic injection of 2-octyl cyanoacrylate for the treatment of gastric variceal bleeding. Surg Endosc. 2019;33:1837-1845. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Bang JY, Al-haddad MA, Chiorean MV, Chalasani NP, Kwo PY, Ghabril M, Lacerda MA, Agrawal S, Masouka H, Vuppalanchi R, Orman ES, Sozio MS, Gawrieh S, Lammert C, Liangpunsakul S, Dewitt JM. Mo1485 Comparison of Direct Endoscopic Injection (DEI) and EUS-Guided Fine Needle Injection (EUS-FNI) of 2-Octyl-Cyanoacrylate for Treatment of Gastric Varices. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;81:AB437. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 22. | Binmoeller KF, Weilert F, Shah JN, Kim J. EUS-guided transesophageal treatment of gastric fundal varices with combined coiling and cyanoacrylate glue injection (with videos). Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;74:1019-1025. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 145] [Cited by in RCA: 169] [Article Influence: 12.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Levy MJ, Wong Kee Song LM, Kendrick ML, Misra S, Gostout CJ. EUS-guided coil embolization for refractory ectopic variceal bleeding (with videos). Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;67:572-574. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Romero-Castro R, Pellicer-Bautista F, Giovannini M, Marcos-Sánchez F, Caparros-Escudero C, Jiménez-Sáenz M, Gomez-Parra M, Arenzana-Seisdedos A, Leria-Yebenes V, Herrerias-Gutiérrez JM. Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS)-guided coil embolization therapy in gastric varices. Endoscopy. 2010;42:E35-E36. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Khoury T, Massarwa M, Daher S, Benson AA, Hazou W, Israeli E, Jacob H, Epstein J, Safadi R. Endoscopic Ultrasound-Guided Angiotherapy for Gastric Varices: A Single Center Experience. Hepatol Commun. 2019;3:207-212. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Kozieł S, Pawlak K, Błaszczyk Ł, Jagielski M, Wiechowska-Kozłowska A. Endoscopic Ultrasound-Guided Treatment of Gastric Varices Using Coils and Cyanoacrylate Glue Injections: Results after 1 Year of Experience. J Clin Med. 2019;8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Ge PS, Bazarbashi AN, Thompson CC, Ryou M. Successful EUS-guided treatment of gastric varices with coil embolization and injection of absorbable gelatin sponge. VideoGIE. 2019;4:154-156. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Bhat YM, Weilert F, Fredrick RT, Kane SD, Shah JN, Hamerski CM, Binmoeller KF. EUS-guided treatment of gastric fundal varices with combined injection of coils and cyanoacrylate glue: a large U.S. experience over 6 years (with video). Gastrointest Endosc. 2016;83:1164-1172. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 138] [Cited by in RCA: 161] [Article Influence: 17.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Zhang HY, He CC, Zhong DF. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided treatment of isolated gastric varices entwined with arteries: A case report. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2024;16:489-493. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |