Published online Jan 16, 2025. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v17.i1.101119

Revised: November 22, 2024

Accepted: December 23, 2024

Published online: January 16, 2025

Processing time: 133 Days and 19.4 Hours

Early anal canal cancer is frequently treated with endoscopic submucosal dis

A 70-year-old woman undergoing follow-up after transverse colon cancer surgery was diagnosed with anal canal cancer extending to the dentate line. The patient underwent a combination of ESD and transanal resection (TAR). The specimen was excised in pieces, which resulted in difficulty performing the pathological evaluation of the margins, especially on the anal side where TAR was performed and severe crushing was observed. Careful follow-up was performed, and local recurrence was observed 3 years postoperatively. Because the patient had super

Anal canal lesions can be safely and reliably removed when ESD and TAR are used appropriately.

Core Tip: Early anal canal cancer is frequently treated with endoscopic submucosal dissection at many institutions to preserve the anal function. However, lesions located in the anal canal are more difficult to resect because of the high risk of bleeding and difficulty of endoscopic manipulation. We encountered a case of early anal canal cancer that recurred after insufficient combined endoscopic submucosal dissection and transanal resection. After improving the treatment technique, complete resection of the lesion was achieved. This report describes the precautions and areas of improvement related to our treatment method.

- Citation: Kinoshita M, Maruyama T, Hike S, Hirosuna T, Kainuma S, Kinoshita K, Nakano A, Ohira G, Uesato M, Matsubara H. Complete resection of recurrent anal canal cancer using endoscopic submucosal dissection and transanal resection: A case report. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2025; 17(1): 101119

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v17/i1/101119.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v17.i1.101119

Early anal canal cancer and early rectal cancer that reach the upper edge of the anal canal or extend into the anal canal can present difficulties during endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) because of poor visualization caused by inadequate dilation of the anal sphincter. Additionally, the well-developed venous plexus in this area can lead to challenges achieving hemostasis[1]. Conversely, when anal canal cancer invades the rectum, transanal resection (TAR) alone may result in poor visibility of the proximal lesion, potentially leading to insufficient resection of the proximal margin. We report a case of anal canal carcinoma extending from the dentate line to the rectum. We performed resection of the lesion using a combination of ESD and TAR as the initial treatment. However, the specimen was severely crushed, thus leading to difficulty performing an accurate pathological evaluation. Additionally, local recurrence occurred. We investigated the problems with the initial treatment and made some improvements. As a result, the second treatment attempt resulted in complete removal of the lesion.

A 70-year-old woman presented without any chief complaint.

One year after laparoscopic right hemicolectomy was performed for transverse colon cancer (pT4aN1M0, pathologic stage IIIa), early anal canal cancer was detected during lower gastrointestinal endoscopy. Therefore, a treatment plan was designed.

The patient had a history of hypertension, diabetes, chronic thyroiditis, and transverse colon cancer.

The patient’s medical history included well-controlled hypertension.

A physical examination indicated that the patient had a height of 166 cm and weight of 49.5 kg.

The carcinoembryonic antigen level was mildly elevated (7.6 ng/mL).

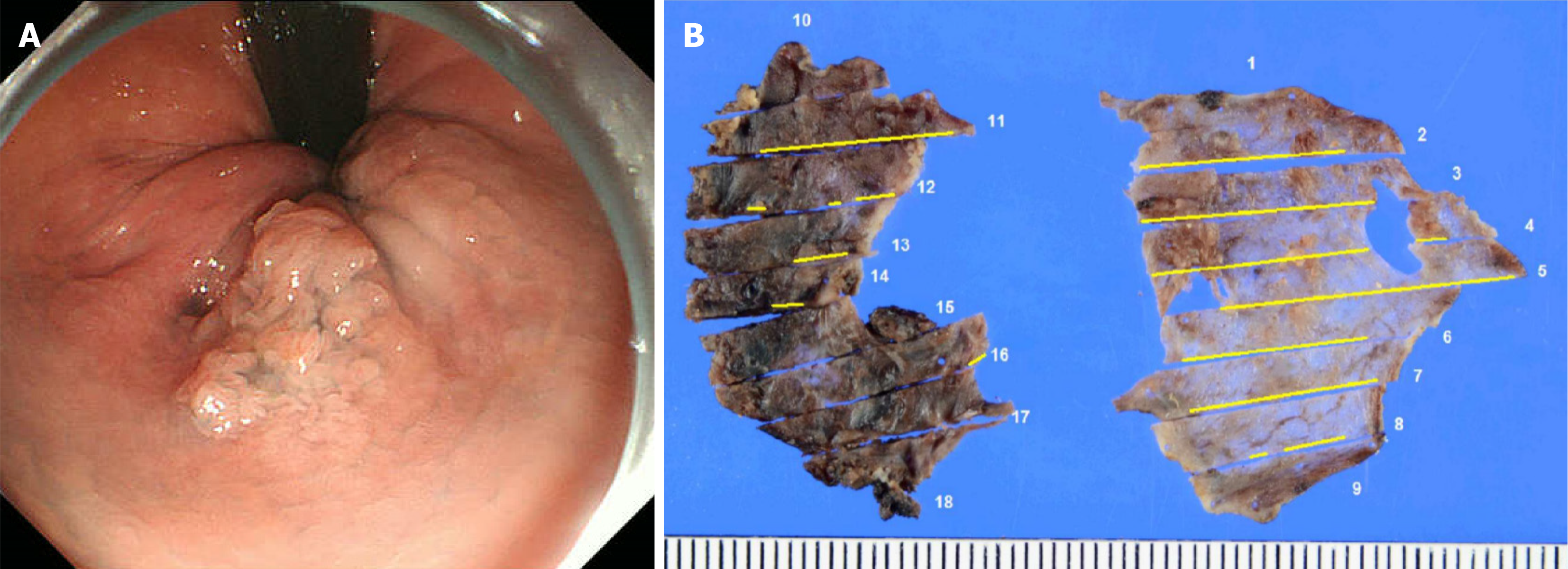

During lower gastrointestinal endoscopy, a 20-mm 0-IIa+Is lesion was observed on the left wall of the anal canal. A lesion extending 5 mm beyond the dentate line was observed on the anal side. The oral side extended slightly beyond the Hermann line into the rectum (Figure 1A). The biopsy results indicated a diagnosis of papillary adenocarcinoma (group 5). Computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging evaluations showed no lymph node or distant metastasis.

The preoperative diagnosis was anal canal cancer (from lower rectum to anal canal, 0-IIa+Is, cT1aN0M0 cStageI).

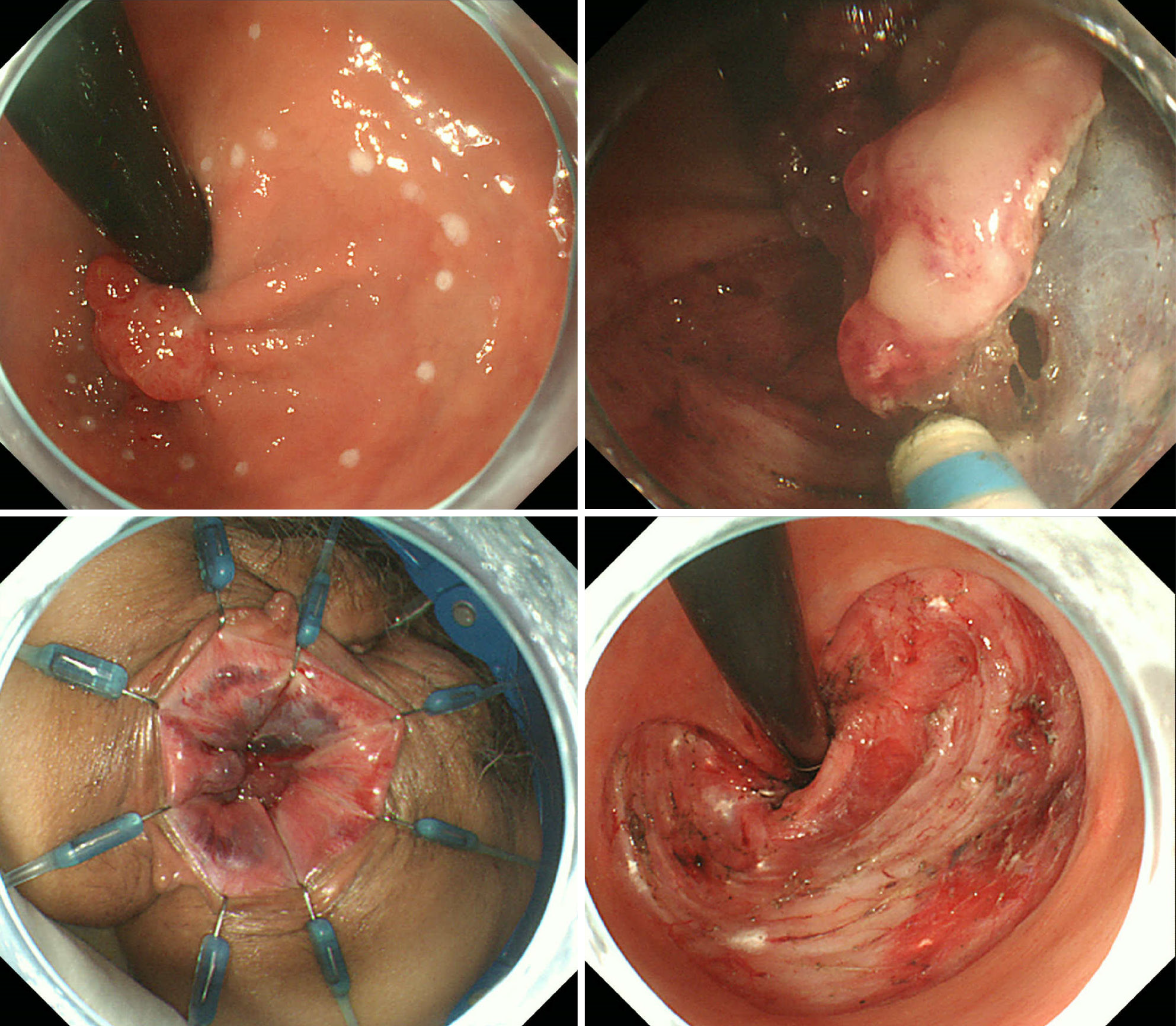

ESD and TAR were performed under general anesthesia with the patient in the lithotomy position. Because of the difficulty visualizing the entire tumor during transanal observation under general anesthesia, ESD was performed on the oral side and TAR was performed on the anal side as planned. A dual knife was used for ESD and a flat electric knife was used for TAR. Different surgeons performed ESD and TAR. ESD was first performed by dissecting from the oral side to near the dentate line. Then, TAR was performed. During TAR, the tumor was dissected and the tumor borders were visually checked. Although the field of view became poor and ESD was considered preferable at times during TAR, it was continued. As a result, the specimen was resected in pieces and severe crushing occurred. The surgery lasted 106 minutes, and blood loss was minimal.

During the initial treatment attempt, two different physicians performed ESD and TAR. After ESD was completed by the first physician, the second physician performed TAR. Therefore, although ESD was necessary during TAR because of the poor field of view that developed, continuation of TAR was necessary, resulting in a fragmented specimen. To achieve an improved outcome, the same physician performed both ESD and TAR appropriately during the second treatment attempt. Additionally, during the initial treatment attempt, precise control of the spatula-type scalpel on the dissection line during TAR with a large cauterization area was difficult and may have caused tumor remnants. Therefore, during the second treatment attempt, a needle-type scalpel was used during TAR to minimize tissue damage. Additionally, we marked the boundaries of the lesions, even areas that were visible to the naked eye, using an endoscopic technique.

First, the lesion borders were marked under endoscopic magnification. ESD on the oral side was performed by dissecting as much of the mucosa as possible. Second, TAR was performed. As dissection from the anal side was con

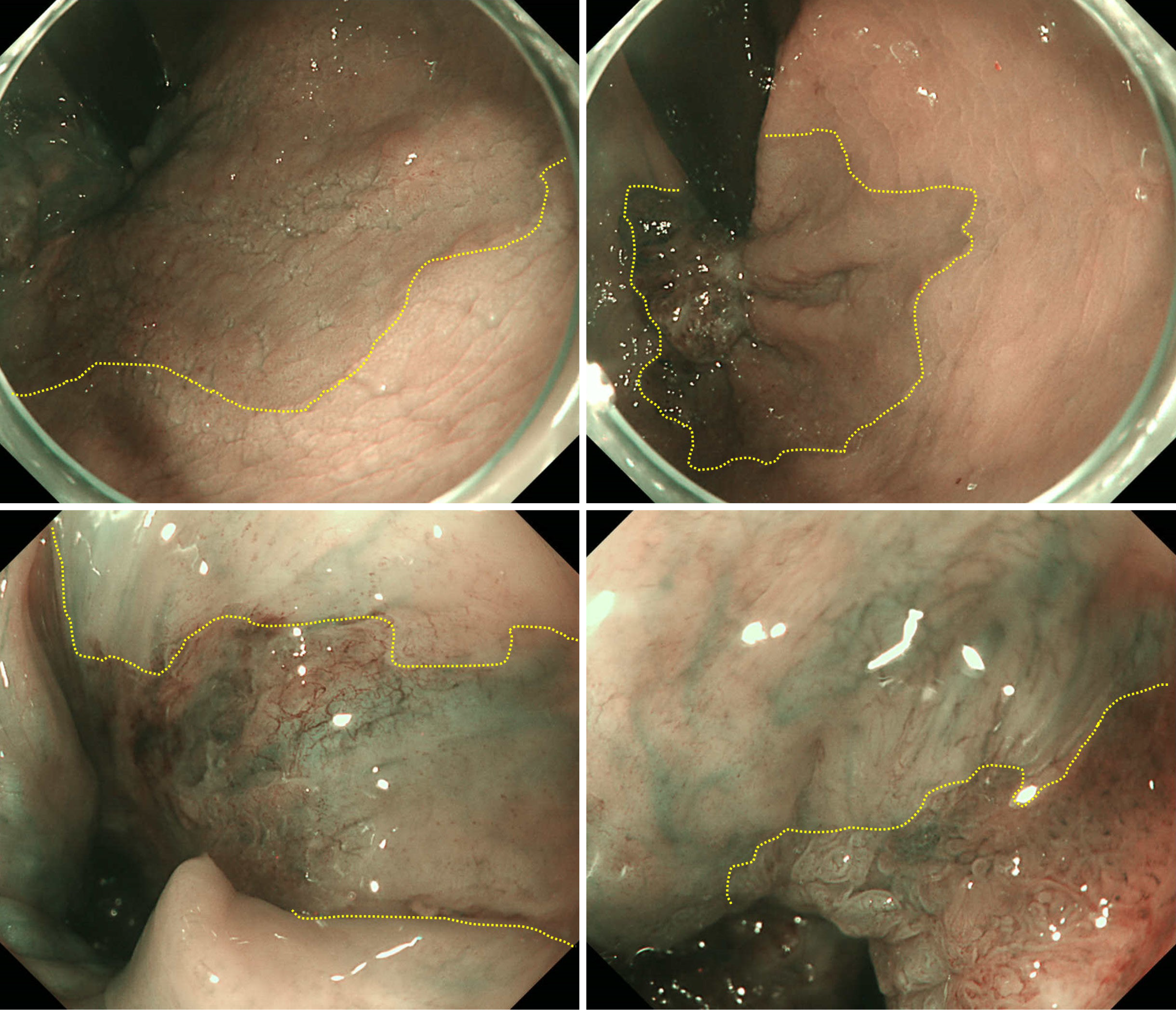

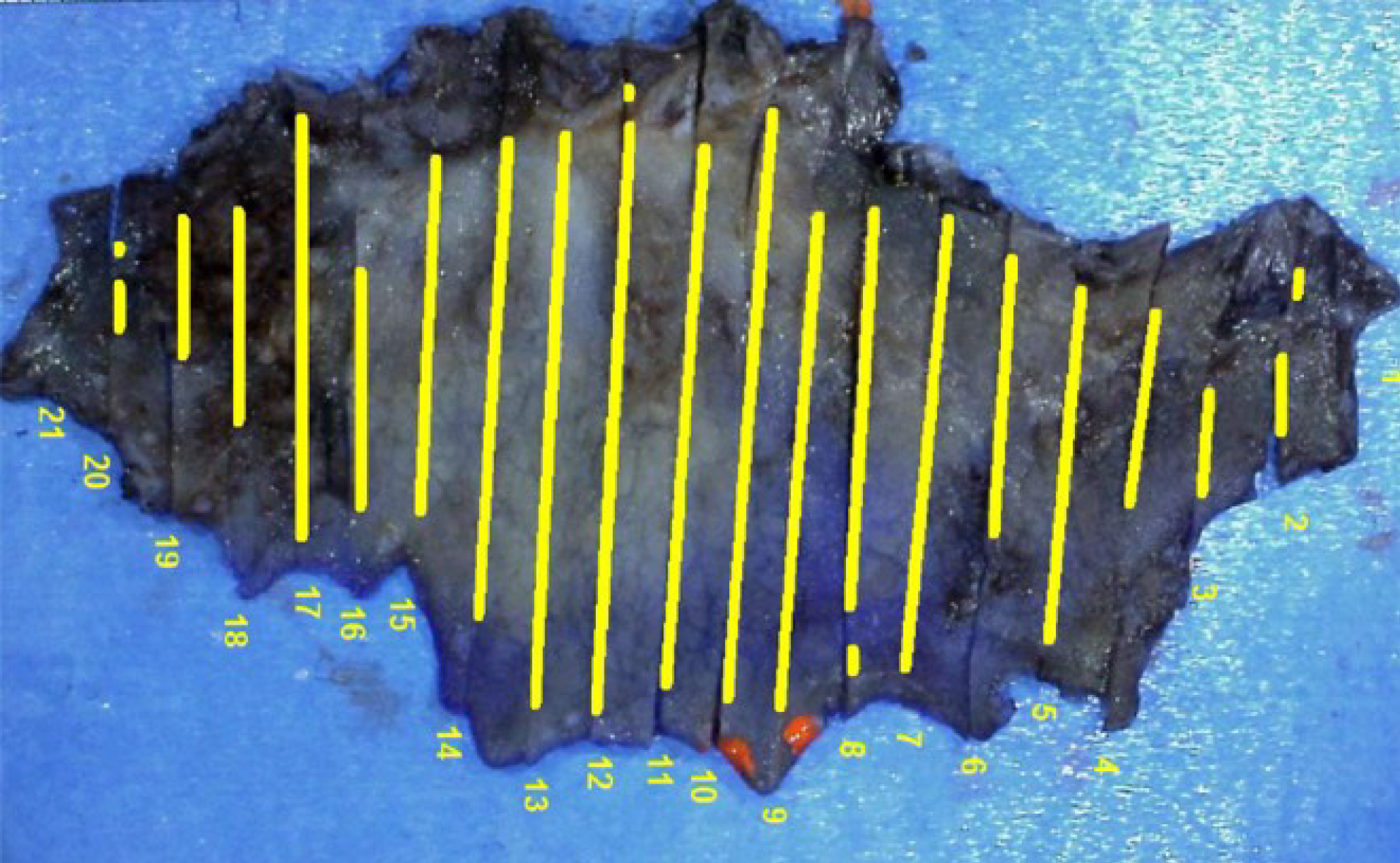

The pathological findings revealed well-differentiated tubular adenocarcinoma and tubular adenoma [from lower rectum to anal canal, type 0-IIa+IIb, 28 mm × 22 mm, tubulin beta-1 (tub1) > papillary adenocarcinoma, pTis, ly0, v0, pHM0 (1000 μm), pVM0 (100 μm)]. However, the specimen was highly damaged, and we determined that an accurate pathological evaluation would be difficult (Figure 1B). Therefore, we conducted careful follow-up that included lower gastrointestinal endoscopy at 6, 12, 24, and 36 months after surgery. Recurrence was detected during lower gastrointestinal endoscopy performed 3 years postoperatively. Recurrence comprised a 20-mm subpedunculated lesion on the left anterior wall of the rectum. The tumor extended into the anal canal. The tumor boundaries were recognizable during narrow band imaging with magnification. However, they were difficult to detect macroscopically because of slight changes in the abnormal blood vessels on the mucosal surface (Figure 3). The biopsy results indicated a diagnosis of adenocarcinoma (tub1 > tub2, group 5). Computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging evaluations confirmed the absence of lymph node metastasis and distant metastasis. Therefore, we decided to proceed with localized treatment. The histopathological findings of reoperation were from lower rectum to anal canal, type 0-IIa+IIc+Isp, 78 mm × 36 mm, tub1 > papillary adenocarcinoma, pTis, ly0, v0, pHM0 (1000 μm), and pVM0 (100 μm) (Figure 4). After surgery, the patient was discharged without any complications and without anal dysfunction. At 2 years and 6 months after surgery, no recurrence was observed.

In Japan, the following factors are associated with a high risk of lymph node metastasis when rectal cancer is treated endoscopically: (1) Submucosal invasion distance ≥ 1000 μm; (2) Positive vascular invasion; (3) Poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma, signet-ring cell carcinoma, or mucinous carcinoma; and (4) Budding grade 2/3 at the invasive front. Complete resection of the lesion in one piece is necessary for an accurate pathological diagnosis, and fragmented and incomplete resections result in a high local recurrence rate[2]. Anal canal cancer is defined by the Colorectal Cancer Treatment Guidelines (Japanese guidelines in 2024) as cancer arising on the anal side of the Hermann line. Anal canal cancer is relatively rare, accounting for approximately 0.7% to 1.8% of all colorectal cancers[3]. Early rectal cancer and adenoma treatment, which aims to preserve the anal function, often includes ESD at many institutions. Despite the high level of endoscopic skills required for ESD, recent advances in endoscopic techniques and device development have improved the safety and en bloc resection rates for large tumors[4].

However, lesions involving the anal canal are challenging because of the narrow lumen and poor visualization caused by the sphincter, which can lead to unstable surgery with only the tip of the scope touching the anal margin. Ad

During the initial surgery, the anal side boundary was confirmed visually, but not endoscopically. Therefore, the boundary may not have been accurate. Additionally, piecemeal resection of the lesion was performed during the initial surgery. This may have occurred because ESD and TAR were performed by different surgeons, thus making it difficult to switch between the two techniques and resulting in continued dissection with an unsuitable technique. During the initial surgery, the flat knife used during TAR likely caused crushing of the tissue and tearing of the specimen, thus making it difficult to evaluate the pathological margin and creating the possibility of residual disease. Therefore, in this case, recurrence may have originated from the resection margin. During the second surgery, a single surgeon performed all procedures. This enabled seamless switching between ESD and TAR. The electric knife vaporized tissue with a high-frequency current, and the needle-type knife with a smaller contact point reduced tissue damage. During reoperation, the use of the needle-type knife during TAR prevented crushing of the tissue and allowed en bloc resection. Before treatment, the lesion borders were marked using ESD techniques.

Understanding the advantages and disadvantages of ESD and TAR and performing them appropriately can result in safe and reliable removal of lesions in the anal canal, which are considered difficult to treat.

| 1. | Toyonaga T, Nishino E, Man-I M, East JE, Azuma T. Principles of quality controlled endoscopic submucosal dissection with appropriate dissection level and high quality resected specimen. Clin Endosc. 2012;45:362-374. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Dekkers N, Dang H, van der Kraan J, le Cessie S, Oldenburg PP, Schoones JW, Langers AMJ, van Leerdam ME, van Hooft JE, Backes Y, Levic K, Meining A, Saracco GM, Holman FA, Peeters KCMJ, Moons LMG, Doornebosch PG, Hardwick JCH, Boonstra JJ. Risk of recurrence after local resection of T1 rectal cancer: a meta-analysis with meta-regression. Surg Endosc. 2022;36:9156-9168. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Choi JY, Jung SA, Shim KN, Cho WY, Keum B, Byeon JS, Huh KC, Jang BI, Chang DK, Jung HY, Kong KA; Korean ESD Study Group. Meta-analysis of predictive clinicopathologic factors for lymph node metastasis in patients with early colorectal carcinoma. J Korean Med Sci. 2015;30:398-406. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Tamegai Y, Saito Y, Masaki N, Hinohara C, Oshima T, Kogure E, Liu Y, Uemura N, Saito K. Endoscopic submucosal dissection: a safe technique for colorectal tumors. Endoscopy. 2007;39:418-422. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 187] [Cited by in RCA: 201] [Article Influence: 11.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Tanaka S, Oka S, Chayama K. Colorectal endoscopic submucosal dissection: present status and future perspective, including its differentiation from endoscopic mucosal resection. J Gastroenterol. 2008;43:641-651. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 183] [Cited by in RCA: 202] [Article Influence: 12.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Pappalardo G, Chiaretti M. Early rectal cancer: a choice between local excision and transabdominal resection. A review of the literature and current guidelines. Ann Ital Chir. 2017;88:183-189. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Kiriyama S, Saito Y, Matsuda T, Nakajima T, Mashimo Y, Joeng HK, Moriya Y, Kuwano H. Comparing endoscopic submucosal dissection with transanal resection for non-invasive rectal tumor: a retrospective study. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;26:1028-1033. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |