Published online Mar 16, 2024. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v16.i3.136

Peer-review started: November 22, 2023

First decision: December 7, 2023

Revised: December 22, 2023

Accepted: January 29, 2024

Article in press: January 29, 2024

Published online: March 16, 2024

Processing time: 112 Days and 20 Hours

Tumor size impacts the technical difficulty and histological curability of colorectal endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD); however, the preoperative evaluation of tumor size is often different from histological assessment. Analyzing influential factors on failure to obtain an accurate tumor size evaluation could help prepare optimal conditions for safer and more reliable ESD.

To investigate the tumor size discrepancy between endoscopic and pathological evaluations and the influencing factors.

This was a retrospective study conducted at a single institution. A total of 377 lesions removed by colorectal ESD at our hospital between April 2018 and March 2022 were collected. We first assessed the difference in size with an absolute per

The mean of absolute percentage in the scaling discordance was 21%, and 91 lesions were considered to be incorrectly estimated in size. The incorrect scaling was significantly remarkable in larger lesions (40 mm vs 28 mm; P < 0.001) and less experience (P < 0.001), and these two factors were influential on the underscaling (75 lesions; P < 0.001). Conversely, compared with the correct scaling group, 16 lesions in the overscaling group were significantly small (20 mm vs 28 mm; P < 0.001), and the small lesion size was influential on the overscaling (P = 0.002).

Lesions indicated for colorectal ESD tended to be underestimated in large tumors, but overestimated in small ones. This discrepancy appears worth understanding for optimal procedural preparation.

Core Tip: Tumor size impacts the technical difficulty and histological curability of colorectal endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD). However, the preoperative evaluation of tumor size is often different from histological assessment. We retrospectively investigated the colorectal tumor size discrepancy between endoscopic and pathological evaluations and influential factors on the discordance. Conclusively, the data demonstrated that the accuracy in the size estimation of candidates for colorectal ESD was influenced by the tumor size and much experience. These lesions tended to be underestimated in large tumors, but overestimated in small ones. This discrepancy appears worth understanding for optimal procedural preparation.

- Citation: Onda T, Goto O, Otsuka T, Hayasaka Y, Nakagome S, Habu T, Ishikawa Y, Kirita K, Koizumi E, Noda H, Higuchi K, Omori J, Akimoto N, Iwakiri K. Tumor size discrepancy between endoscopic and pathological evaluations in colorectal endoscopic submucosal dissection. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2024; 16(3): 136-147

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v16/i3/136.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v16.i3.136

Colorectal cancer is one of the most common malignancies and relevant disease worldwide[1]. The early detection and treatment of this disease are significant to prolong life expectancy; therefore, aggressive removal of colorectal polyps including precancerous lesions is recommended using colonoscopy[2,3].

Small colorectal polyps can be easily removed by polypectomy or endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR), whereas large lesions require technically challenging techniques including endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD). Due to anatomical characteristics, including a thin intestinal wall and the presence of folds and bends, colorectal ESD is technically more difficult than upper gastrointestinal tract ESD. Intraoperative perforation, which is one of the major adverse events in colorectal ESD, is reported to be 1.3%-18.0%[4-7]. Influential factors on the perforation in colorectal ESD include tumor diameter, fibrosis, and flexure[5]. Moreover, it is reported that a larger tumor[6,7], less experience of endoscopists[6], and paradoxical movement[7] are independent factors contributing to the difficulty of colorectal ESD. Particularly, a strong correlation is observed between tumor diameter and treatment duration[8].

Accordingly, an accurate understanding of tumor characteristics including tumor size, is significant for a safe and time-saving procedure. However, the preoperative estimation of the tumor diameter is often different from the postoperative histological size, and when a novice endoscopist is to treat an unexpectedly large lesion, unfavorable events can occur with a long procedural time.

There have been several studies on the discrepancy in the tumor diameter of colorectal neoplasia[9-12]. However, these studies are mainly on small polyps, wherein tumors of approximately 10 mm are believed to be often overestimated[9,10]. Conversely, pieces of evidence remain lacking on large tumors[12], particularly tumors that can be candidates for resection by ESD.

In this study, to investigate the accuracy of the preoperative endoscopic evaluation of tumor size, we retrospectively assessed the discrepancy between pre- and postoperatively evaluated tumor diameters of lesions that are indicated for colorectal ESD. Subsequently, influential factors on failure for an accurate tumor size evaluation were investigated.

This was a retrospective study conducted at a single institution. In accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, we obtained approval from the institutional review board of our hospital before study initiation. Consent from each patient was obtained as an opt-out; therefore, written consent was waived.

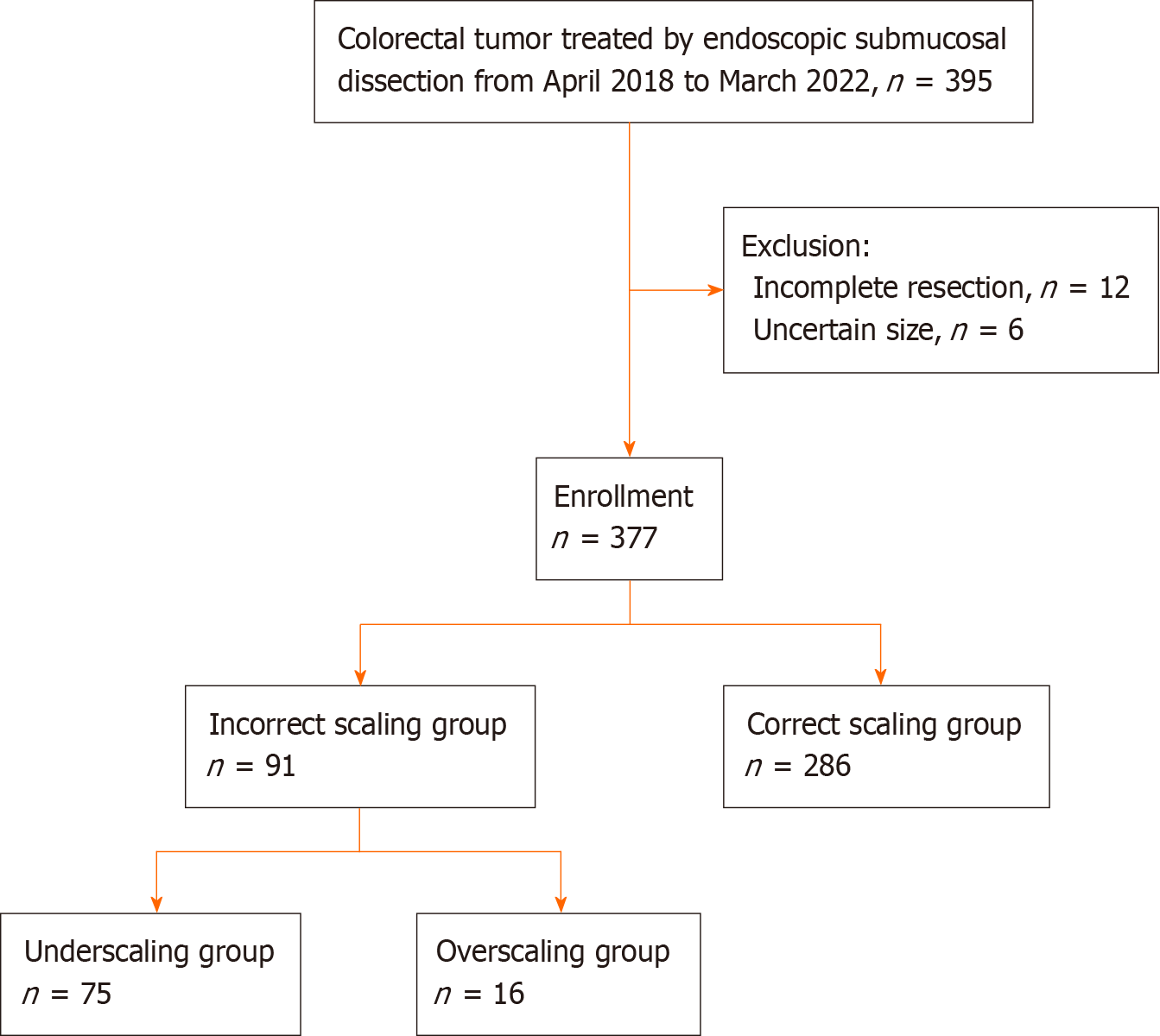

Of the 395 lesions removed by colorectal ESD performed between April 2018 and March 2022, 6 lesions with insufficient description of data on preoperative and/or pathological tumor diameter and 12 lesions with incomplete resection were excluded. Finally, we collected 377 lesions in this study (Figure 1).

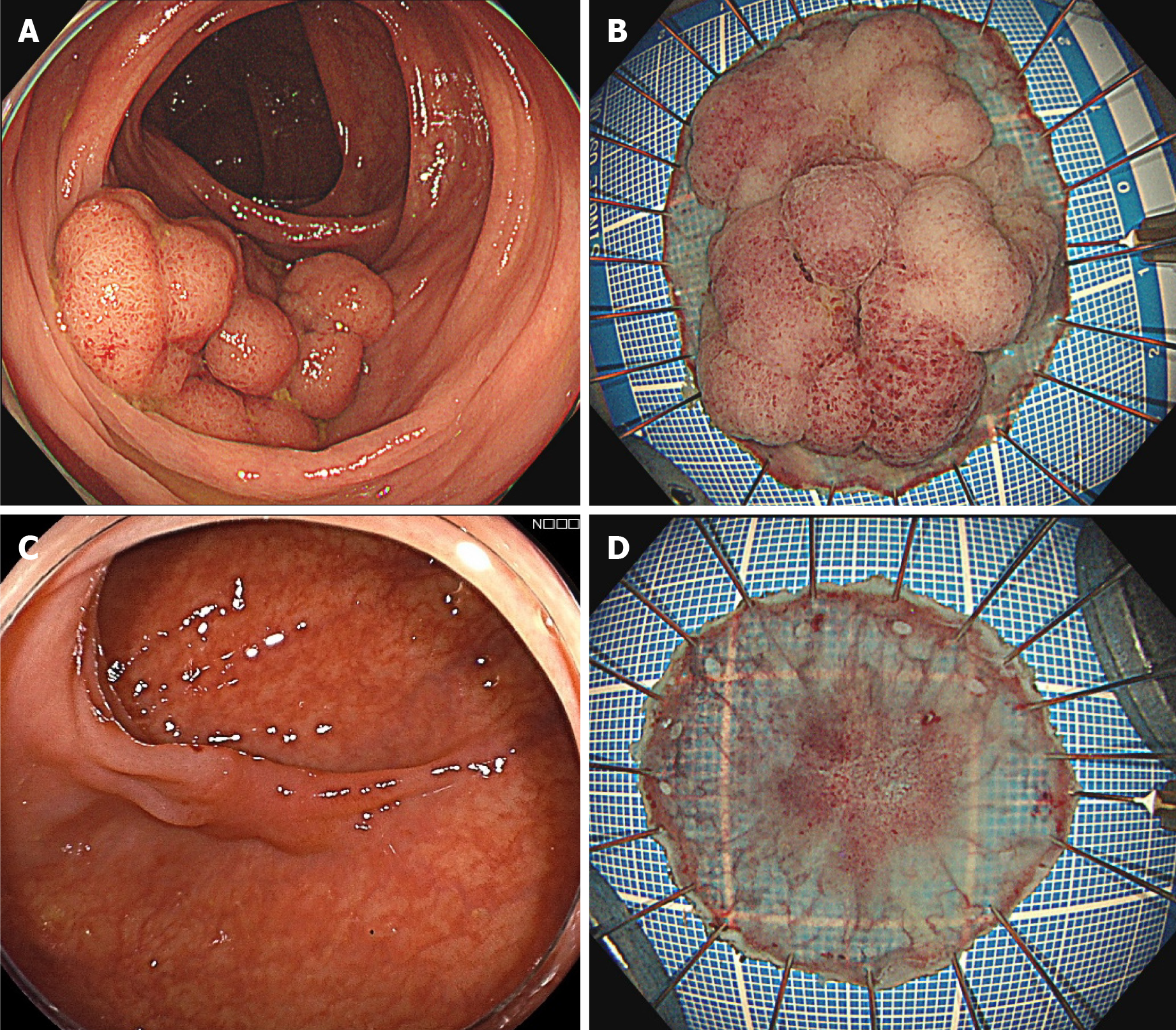

ESD indication criteria were based on the Japanese Colorectal ESD/EMR guidelines[4]. We mainly used the PCF-290ZI endoscope (Olympus Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) with a transparent straight hood (D-201-12704; Olympus) under carbon dioxide insufflation. A 0.4% sodium hyaluronate solution (Ksmart; Olympus) diluted five times with normal saline, which included a small amount of indigo carmine, was used for submucosal injection. A mucosal incision was made around the tumor, and submucosal dissection for en bloc removal was performed using the DualKnife (KD-655Q; Olympus). A high-frequency generator (VIO 3; Erbe Elektromedizin GmbH, Tübingen, Germany) was used during ESD. ST-hood (DH-29CR; Fujifilm Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan), hemostatic forceps (FD-411QR; Olympus), or other endoscopic devices were used according to the situation. The transanally retrieved specimen was promptly spread, pinned on a sponge board, and immersed into 10% neutral buffered formalin for fixation for histological evaluation by pathologists.

For the preoperative tumor size evaluation, we referred to endoscopic reports, which were documented in preoperative colonoscopy before ESD. The tumor size, which was described as the largest diameter, was obtained from the endoscopic report at our institution when we performed the preoperative check or at other clinics where the tumor was indicated and introduced to us when ESD was directly booked without preoperative colonoscopy at our institution.

Postoperative size evaluation was performed using the largest diameter on the pathological report. In detail, board-certificated pathologists evaluated the specimen, which was sliced at 2-3-mm intervals. Based on the final pathological diagnosis, the pathologists in charge demarcated the neoplastic area on the specimen photo that was taken before slicing, and the maximal diameter of the tumor was described in a pathological report.

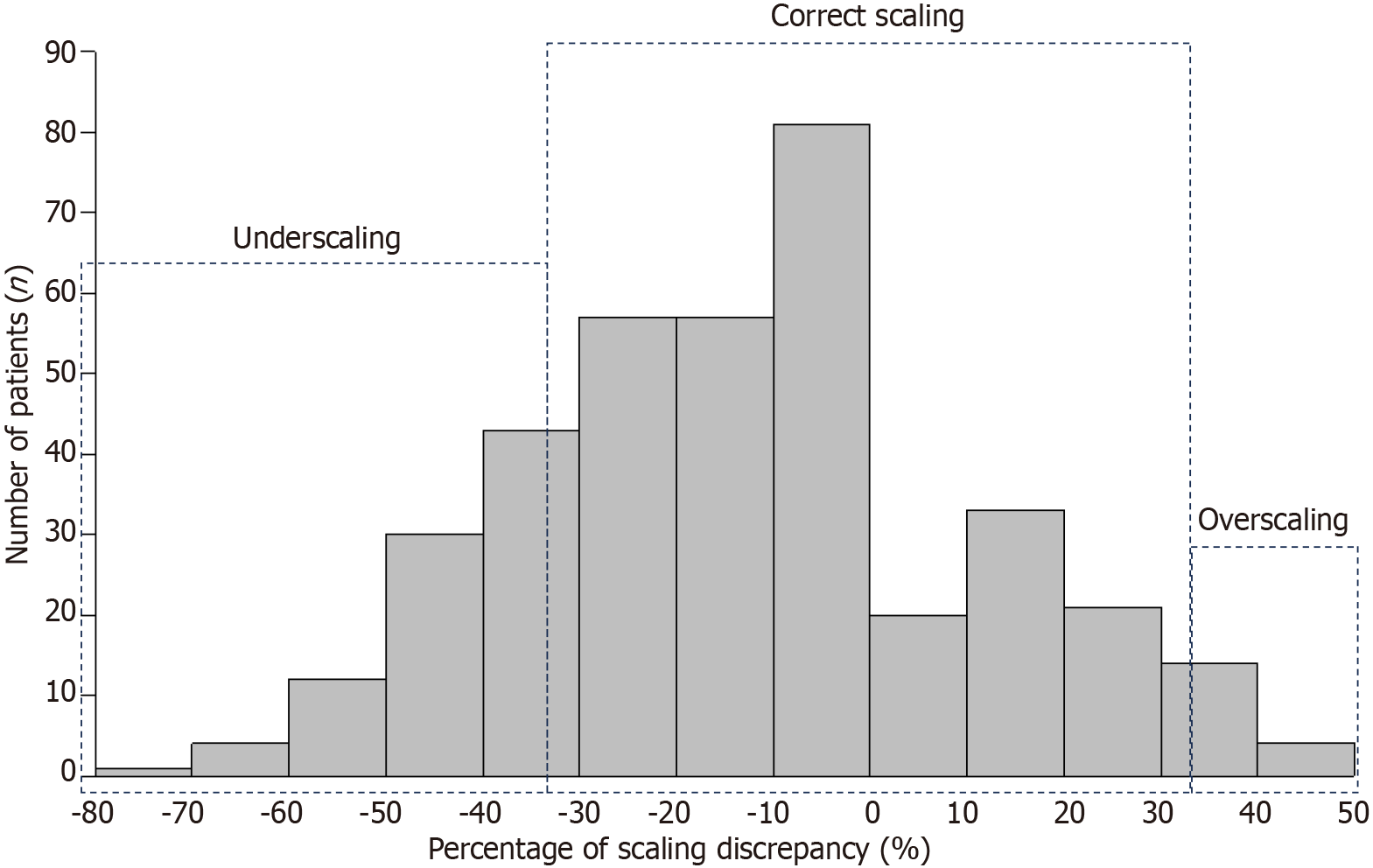

As a primary outcome measure, the scaling discrepancy, which indicated an absolute percentage of the size discordance (a preoperatively estimated endoscopic diameter minus a postoperatively measured histological diameter) in a postoperatively measured diameter, was evaluated (Figure 2). Subsequently, lesions were divided into the following two groups according to the degree of discrepancy: The correct scaling group (> -33% and < 33% of the discordance) and the incorrect scaling group (≤ -33% or ≥ 33% of the discordance). Lesion-related parameters including pathological size, location, morphology, histology, localization, and degree of circumference were used to investigate influential factors on the discrepancy. Furthermore, endoscopist-related parameters included the experience of endoscopists who performed preoperative colonoscopy and the hospital type where the preoperative colonoscopy was performed. The multivariate analysis was followed by univariate analyses, which focused on the tumor size, location, and other parameters that seemed to be influential by showing that the P value was < 0.1 in the preceding univariate analysis.

As secondary outcome measures, the abovementioned parameters were compared between the underscaling (-33% or less of the discrepancy) and correct scaling groups as well as between the overscaling (33% or more of the discrepancy) and correct scaling groups, respectively. Subsequently, multivariate analysis was performed in terms of the following relevant parameters on size estimation: Pathological size, location, and possible influential factors (P < 0.1) in the univariate analysis. When the size, a continuous parameter, was indicated as the influential factor, we drew a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve to investigate an optimal cut-off value of the size to differentiate the under/overscaling group from the correct scaling group.

Tumor locations were grouped into the colon and rectum. Morphology was divided into the following two macroscopic groups according to the Paris classification: The protruded type, which is 0-I with protruded features; and the flat type, which is 0-II with flat features. Histology was grouped into adenoma and adenocarcinoma. Regarding the localization, we focused on whether the lesion is over the haustra because it may hamper an entire lesion in a single visual field. Regarding the degree of circumference, lesions were divided into two groups by setting one-third as the cut-off value. The experience of endoscopists was classified on the basis of the years of experience in endoscopy and the number of ESD performed; those with 5 years or more of endoscopic experience and at least 100 cases of ESD were defined as experienced, and those who did not meet these criteria were defined as less-experienced. As all doctors at the clinics were general physicians and their experience in ESD is unknown, they were defined as less-experienced in this study. Regarding the hospital type, we set two groups, a referral hospital (our institution) and clinics, according to where the preoperative colonoscopy was performed just before ESD.

Categorical variables were analyzed using the chi-squared test or Fisher’s exact test. Continuous variables were tested for normality and analyzed using the Mann-Whitney U test between the two groups and using the Kruskal-Wallis H test among the three groups. To adjust for potential confounders, we used multivariate logistic regression. The Pearson product-moment correlation coefficient was used for regression analysis. The cut-off value was evaluated in the point with the highest Youden’s index. All statistical analyses were performed using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (version 27, IBM, Armonk, NY, United States), and P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

The mean age of patients was 70 years, and 61% of them were males. Approximately one-fifth of cases were located on the rectum. The number of experienced endoscopists in preoperative diagnosis was almost similar to that of less-experienced endoscopists. The mean size of preoperatively estimated and postoperatively measured tumors was 26.0 mm ± 10.5 mm and 31.0 mm ± 15.2 mm, respectively, and the mean of absolute percentage in the scaling discordance between pre- and postoperative evaluations was 21.0% ± 15.4% (Table 1). The distribution of lesions regarding the discordance is shown in Figure 3.

| Item | Value |

| Background characteristics | n = 377 |

| Lesion-related factors | |

| Age in yr, mean | 70 |

| Sex | |

| Male | 231 (61) |

| Female | 146 (39) |

| Location | |

| Colon | 298 (79) |

| Rectum | 79 (21) |

| Morphology | |

| Protruded | 84 (22) |

| Flat | 293 (78) |

| Histology | |

| Adenoma | 84 (22) |

| Adenocarcinoma | 293 (78) |

| Localization | |

| Over the haustra | 212 (56) |

| On a flat lumen | 165 (44) |

| Degree of circumference | |

| ≥ 1/3 | 40 (11) |

| < 1/3 | 337 (89) |

| Endoscopist-related factors | |

| Experience | |

| Experienced | 186 (50) |

| Less-experienced | 191 (50) |

| Hospital type | |

| Referral hospital | 351 (93) |

| Clinics | 26 (7) |

| Size assessment | |

| Endoscopic size in mm, mean ± SD | 26.0 ± 10.5 |

| Histological size in mm, mean ± SD | 31.0 ± 15.2 |

| Absolute percentage of the size discordance, mean ± SD | 21.0 ± 15.4 |

Regarding the scaling discrepancy, the numbers of lesions in the incorrect and correct scaling groups were 91 and 286, respectively (Figure 1). As shown in Table 2, large lesions, the involvement of the haustra, over one-third of the lumen, and the assessment by less-experienced are significantly common in the incorrect scaling group. Multivariate analysis demonstrated that larger tumor size and less experience were significantly influential on the incorrect scaling of the size assessment (Table 3).

| Item | Incorrect scaling group | Correct scaling group | P value |

| n = 91 | n = 286 | ||

| Lesion-related factors | |||

| Pathological size in mm, mean | 40 | 28 | < 0.001 |

| Location | 0.750 | ||

| Colon | 73 (80) | 225 (79) | |

| Rectum | 18 (20) | 61 (21) | |

| Morphology | 0.210 | ||

| Protruded | 16 (18) | 68 (24) | |

| Flat | 75 (82) | 218 (76) | |

| Histology | 0.830 | ||

| Adenoma | 21 (23) | 63 (22) | |

| Adenocarcinoma | 70 (77) | 223 (78) | |

| Localization | 0.001 | ||

| Over the haustra | 65 (71) | 147 (51) | |

| On a flat lumen | 26 (29) | 139 (49) | |

| Degree of circumference | < 0.001 | ||

| ≥ 1/3 | 21 (23) | 19 (7) | |

| < 1/3 | 70 (77) | 267 (93) | |

| Endoscopist-related factors | |||

| Experience | 0.050 | ||

| Experienced | 37 (41) | 150 (52) | |

| Less-experienced | 54 (59) | 136 (48) | |

| Hospital type | 0.900 | ||

| Referral hospital | 85 (93) | 266 (93) | |

| Clinics | 6 (7) | 20 (7) | |

| Factor | Odds ratio | 95%CI | P value |

| Pathological size | 1.05 | 1.030-1.080 | < 0.001 |

| Location | |||

| Rectum | 1.00 | ||

| Colon | 1.20 | 0.612-2.360 | 0.590 |

| Localization | |||

| Over the haustra | 1.00 | ||

| On a flat lumen | 1.56 | 0.877-2.750 | 0.130 |

| Degree of circumference | |||

| < 1/3 | 1.00 | ||

| ≥ 1/3 | 1.09 | 0.414-2.870 | 0.860 |

| Experience | |||

| Less-experienced | 1.00 | ||

| Experienced | 0.44 | 0.259-0.760 | 0.003 |

The incorrect scaling group (91 lesions) was further divided into the under- and overscaling groups, with 75 and 16 lesions, respectively (Figure 1). As shown in Table 4, the influential factors on underscaling include tumor size, the involvement of the haustra, and over one-third of the lumen. Multivariate analysis showed that larger size and less experience significantly affected the underestimation of the scaling in lesion size (Table 5). The ROC curve indicated that the optimal cut-off value was 29.5 mm in 0.779 of the maximal area under the curve (AUC), with sensitivity and specificity of 80.0% and 69.9%, respectively.

| Item | Underscaling group | Correct scaling group | P value |

| n = 75 | n = 286 | ||

| Lesion-related factors | |||

| Pathological size in mm, mean | 44 | 28 | < 0.001 |

| Location | 0.800 | ||

| Colon | 58 (77) | 225 (79) | |

| Rectum | 17 (23) | 61 (21) | |

| Morphology | 0.150 | ||

| Protruded | 12 (16) | 68 (24) | |

| Flat | 63 (84) | 218 (76) | |

| Histology | 0.400 | ||

| Adenoma | 20 (27) | 63 (22) | |

| Adenocarcinoma | 55 (73) | 223 (78) | |

| Localization | 0.001 | ||

| Over the haustra | 54 (72) | 147 (51) | |

| On a flat lumen | 21 (28) | 139 (49) | |

| Degree of circumference | < 0.001 | ||

| ≥ 1/3 | 20 (27) | 19 (7) | |

| < 1/3 | 55 (73) | 267 (93) | |

| Endoscopist-related factor | |||

| Experience | 0.056 | ||

| Experienced | 30 (40) | 150 (52) | |

| Less-experienced | 45 (60) | 136 (48) | |

| Hospital type | 0.760 | ||

| Referral hospital | 69 (92) | 266 (93) | |

| Clinics | 6 (7) | 20 (7) | |

| Factor | Odds ratio | 95%CI | P value |

| Pathological size | 1.08 | 1.05-1.11 | < 0.001 |

| Location | |||

| Rectum | 1.00 | ||

| Colon | 1.07 | 0.510-2.250 | 0.840 |

| Localization | |||

| On a flat lumen | 1.00 | ||

| Over the haustra | 1.36 | 0.705-2.600 | 0.340 |

| Degree of circumference | |||

| < 1/3 | 1.00 | ||

| ≥ 1/3 | 0.65 | 0.227-1.890 | 0.290 |

| Experience | |||

| Less-experienced | 1.00 | ||

| Experienced | 0.36 | 0.192-0.666 | 0.001 |

Regarding overscaling, tumor size was the sole influential factor. However, lesions in the overscaling group were smaller than those in the correct scaling group, which was the opposite result in the analysis on underscaling (Table 6). Multivariate analysis showed that smaller size was significantly influential on overscaling (Table 7). In the ROC curve, the optimal cut-off value was 18.5 mm when the maximal AUC was 0.768, with sensitivity and specificity of 88.5% and 56.2%, respectively.

| Factor | Overscaling group | Correct scaling group | P value |

| n = 16 | n = 286 | ||

| Lesion-related factors | |||

| Pathological size in mm, mean | 20 | 28 | < 0.001 |

| Location | 0.210 | ||

| Colon | 15 (94) | 225 (79) | |

| Rectum | 1 (6) | 61 (21) | |

| Morphology | 1.000 | ||

| Protruded | 4 (25) | 68 (24) | |

| Flat | 12 (75) | 218 (76) | |

| Histology | 0.210 | ||

| Adenoma | 1 (6) | 63 (22) | |

| Adenocarcinoma | 15 (94) | 223 (78) | |

| Localization | 0.180 | ||

| Over the haustra | 11 (69) | 147 (51) | |

| On a flat lumen | 5 (31) | 139 (49) | |

| Degree of circumference | 1.000 | ||

| ≥ 1/3 | 1 (6) | 19 (7) | |

| < 1/3 | 15 (94) | 267 (93) | |

| Endoscopist-related factor | |||

| Experience | 0.500 | ||

| Experienced | 7 (44) | 150 (52) | |

| Less-experienced | 9 (56) | 136 (48) | |

| Hospital type | 0.610 | ||

| Referral hospital | 16 (100) | 266 (93) | |

| Clinics | 0 (0) | 20 (7) | |

| Factor | Odds ratio | 95%CI | P value |

| Pathological size | 0.86 | 0.779-0.945 | 0.002 |

| Location | |||

| Rectum | 1.00 | ||

| Colon | 3.67 | 0.464-29.000 | 0.220 |

The present study showed that the tumor size was approximately ± 20% of the scaling discrepancy before colorectal ESD. One-fourth of those lesions were incorrectly evaluated in size, mainly toward the underestimation; this tendency was likely observed in large tumors > 3 cm and less-experienced endoscopists. By contrast, the overestimation, although occurred less frequently, tended to be made in smaller lesions < 2 cm. Overall, in the preoperative colonoscopy before ESD, lesions at both extremities in size were likely to be adjusted to the moderate diameter.

In this study, the mean pathological diameter of colorectal lesions that were removed by ESD was 31 mm, whereas the mean preoperative endoscopic evaluation diameter was 26 mm, indicating that the lesion size was almost correctly estimated before the procedure. The mean scaling discrepancy (± 21%) appeared to be an acceptable discordance. However, considering that the correct scaling was defined as from -33% to 33% of discrepancies, one-fourth (91/377) of lesions were incorrectly evaluated preoperatively. Multivariate analysis suggested that large lesions and less experience were independent influential factors on incorrect scaling. Regarding large lesions, the reason for the incorrect scaling may be attributed to the structure of the lens mounted on an endoscope. An endoscopic lens is designed as a fish-eye, which can visualize a wider field than reality. Therefore, a large objective tends to appear smaller. On the other hand, less ESD experience may contribute to incorrect size evaluation of large lesions due to less experience both in visualizing the actual specimen pinned following ESD and reviewing pathological results. In clinical practice, endoscopists can adjust the preoperative endoscopic size to the actual pathological size by repeatedly reviewing pathological diagnoses of endoscopically removed polyps. However, lesions that are candidates for ESD are not frequently encountered compared with small polyps. Therefore, endoscopists with less ESD experience should have less opportunity of providing feedback on the pathological diagnosis of ESD to further endoscopic evaluation.

In the incorrect scaling, underestimation mainly occurred in 82% of lesions (75/91). The comparison between the underscaling and correct scaling groups showed similar results to that between the incorrect and correct scaling groups. This suggests that the abovementioned speculations are considered appropriate. Particularly, lesions > 3 cm in actual size are inclined to be underscaled, as indicated in the ROC curve analysis. In contrast, 18% of the incorrect scaling was misdiagnosed as overestimation. Interestingly, the overestimation was also influenced by lesion size; however, small lesions tend to appear larger, which is the opposite phenomenon of underestimation. This reason may not be because of endoscopic visualization but the indication criteria of colorectal ESD. Considering the medical insurance from the Japanese government, the indication criteria of colorectal ESD for cancers are lesions ≥ 2 or ≥ 1 cm with possible severe submucosal fibrosis. In this condition, when endoscopists detect a small tumor that should be removed in an en bloc fashion but consider it difficult by snaring, they may be psychologically inclined to diagnose it as larger than the actual size to meet the ESD criteria. The small number of lesions in the overscaling group may be due to the nature of the lesions included in this study. Previous studies have indicated that small polyps are likely to be overestimated[9,10]. In this study, the lesions were relatively large because this study included lesions removed by ESD. Therefore, we consider that the lesions in this study were less likely to be overscaled.

If we are aware that the larger the lesion appears, the much larger it may be, we can prepare an optimal condition for safe and reliable ESD as per operator’s discretion, including an endoscopic room for a long procedure time and the degree of sedation needed. Moreover, appropriate informed consent can be provided to patients and families. This tendency will be more distinct when the preoperative colonoscopy is performed by an endoscopist with less experience. Conversely, when an ESD candidate is small, it may be smaller than it appears, thereby making it suitable for removal via snaring resection, wherein unnecessary ESD can be avoided; however, sufficient technical skills for en bloc EMR are required.

This study had several limitations. First, it was a retrospective single-center study. Second, several endoscopists and pathologists were involved in the pre- and postoperative diagnoses, respectively. Third, since the shape of tumors was flexibly changed under intraluminal conditions, some lesion characteristics regarding the haustra or the degree of circumference could not be completely objective. Fourth, the threshold of discrepancies (33%) was subjectively determined in this study because referable previous papers were lacking. Lastly, the tumor size was slightly shortened following fixation with formalin; however, this change should be negligible[13].

The present study demonstrated that the accuracy in preoperative size estimation of large colorectal tumors that could be indicated for ESD was influenced by the tumor size and much experience. These lesions tended to be underestimated in large tumors, whereas overestimated in small ones, suggesting that endoscopists, particularly less-experienced in ESD, were inclined to change the lesions to a “moderate” size. The understanding of this discrepancy may be helpful for preoperative informed consent for patients and the decision-making of operative conditions.

Pathological assessment of tumor size often differs from preoperative evaluation, which could render treatment difficult. This study retrospectively investigated size discrepancies between endoscopic and pathological assessment and factors influencing this discordance.

The preoperative estimation of the tumor size is often different from the postoperative histological size, and when a novice endoscopist is to treat an unexpectedly large lesion, unfavorable events can occur with a long procedural time. Accordingly, an accurate understanding of tumor characteristics including tumor size, is significant for a safe and time-saving procedure.

To analyze the discrepancy between tumor size in endoscopic and pathological assessment and the factors influencing this discrepancy will enable a more accurate prediction of tumor size in the preoperative phase.

We included 377 lesions removed with colorectal endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) at our hospital between April 2018 and March 2022. We classified three groups to analyze the discrepancy by size variation: Overestimation, underestimation, and the correct diagnosis groups. We compared clinicopathological characteristics among these groups.

We showed that the larger the lesion, the more likely it is to be underestimated. This preoperative underestimation was contrary to previous reports for small polyps. The larger the lesion, the longer the ESD treatment time needed because ESD treatment time is influenced by lesion size. The present study results revealed that larger lesions should be assumed to require longer-than-predicted treatment time.

Recognizing that the larger the lesion appears, the more likely it is to be a larger lesion, optimal conditions for safe and reliable ESD can be prepared according to the operator’s judgment, including an operation room for longer procedure times and the degree of sedation required.

To investigate how tumor size discrepancies between endoscopic and pathological assessment affect ESD outcomes.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: Japan

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Cho J, South Korea; Shi RH, China S-Editor: Chen YL L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Zhao YQ

| 1. | Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, Bray F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71:209-249. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75126] [Cited by in RCA: 64542] [Article Influence: 16135.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (176)] |

| 2. | Tanaka S, Kashida H, Saito Y, Yahagi N, Yamano H, Saito S, Hisabe T, Yao T, Watanabe M, Yoshida M, Saitoh Y, Tsuruta O, Sugihara KI, Igarashi M, Toyonaga T, Ajioka Y, Kusunoki M, Koike K, Fujimoto K, Tajiri H. Japan Gastroenterological Endoscopy Society guidelines for colorectal endoscopic submucosal dissection/endoscopic mucosal resection. Dig Endosc. 2020;32:219-239. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 138] [Cited by in RCA: 270] [Article Influence: 54.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Park CH, Yang DH, Kim JW, Kim JH, Min YW, Lee SH, Bae JH, Chung H, Choi KD, Park JC, Lee H, Kwak MS, Kim B, Lee HJ, Lee HS, Choi M, Park DA, Lee JY, Byeon JS, Park CG, Cho JY, Lee ST, Chun HJ. Clinical Practice Guideline for Endoscopic Resection of Early Gastrointestinal Cancer. Clin Endosc. 2020;53:142-166. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 108] [Article Influence: 21.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Rahmi G, Hotayt B, Chaussade S, Lepilliez V, Giovannini M, Coumaros D, Charachon A, Cholet F, Laquière A, Samaha E, Prat F, Ponchon T, Bories E, Robaszkiewicz M, Boustière C, Cellier C. Endoscopic submucosal dissection for superficial rectal tumors: prospective evaluation in France. Endoscopy. 2014;46:670-676. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Hori K, Uraoka T, Harada K, Higashi R, Kawahara Y, Okada H, Ramberan H, Yahagi N, Yamamoto K. Predictive factors for technically difficult endoscopic submucosal dissection in the colorectum. Endoscopy. 2014;46:862-870. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 88] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Zhu M, Xu Y, Yu L, Niu YL, Ji M, Li P, Shi HY, Zhang ST. Endoscopic submucosal dissection for colorectal laterally spreading tumors: Clinical outcomes and predictors of technical difficulty. J Dig Dis. 2022;23:228-236. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Sato K, Ito S, Kitagawa T, Kato M, Tominaga K, Suzuki T, Maetani I. Factors affecting the technical difficulty and clinical outcome of endoscopic submucosal dissection for colorectal tumors. Surg Endosc. 2014;28:2959-2965. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 102] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Agapov M, Dvoinikova E. Factors predicting clinical outcomes of endoscopic submucosal dissection in the rectum and sigmoid colon during the learning curve. Endosc Int Open. 2014;2:E235-E240. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Anderson BW, Smyrk TC, Anderson KS, Mahoney DW, Devens ME, Sweetser SR, Kisiel JB, Ahlquist DA. Endoscopic overestimation of colorectal polyp size. Gastrointest Endosc. 2016;83:201-208. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Eichenseer PJ, Dhanekula R, Jakate S, Mobarhan S, Melson JE. Endoscopic mis-sizing of polyps changes colorectal cancer surveillance recommendations. Dis Colon Rectum. 2013;56:315-321. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Schoen RE, Gerber LD, Margulies C. The pathologic measurement of polyp size is preferable to the endoscopic estimate. Gastrointest Endosc. 1997;46:492-496. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 136] [Cited by in RCA: 145] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Buijs MM, Steele RJC, Buch N, Kolbro T, Zimmermann-Nielsen E, Kobaek-Larsen M, Baatrup G. Reproducibility and accuracy of visual estimation of polyp size in large colorectal polyps. Acta Oncol. 2019;58:S37-S41. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Moug SJ, Vernall N, Saldanha J, McGregor JR, Balsitis M, Diament RH. Endoscopists' estimation of size should not determine surveillance of colonic polyps. Colorectal Dis. 2010;12:646-650. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |