Published online Nov 16, 2024. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v16.i11.607

Revised: September 13, 2024

Accepted: October 9, 2024

Published online: November 16, 2024

Processing time: 125 Days and 14.7 Hours

Ulcerative colitis (UC) with concomitant primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC) represents a distinct disease entity (PSC-UC). Mayo endoscopic subscore (MES) is a standard tool for assessing disease activity in UC but its relevance in PSC-UC remains unclear.

To assess the accuracy of MES in UC and PSC-UC patients, we performed histological scoring using Nancy histological index (NHI).

MES was assessed in 30 PSC-UC and 29 UC adult patients during endoscopy. NHI and inflammation were evaluated in biopsies from the cecum, rectum, and terminal ileum. In addition, perinuclear anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies, fecal calprotectin, body mass index, and other relevant clinical characteristics were collected.

The median MES and NHI were similar for UC patients (MES grade 2 and NHI grade 2 in the rectum) but were different for PSC-UC patients (MES grade 0 and NHI grade 2 in the cecum). There was a correlation between MES and NHI for UC patients (Spearman's r = 0.40, P = 0.029) but not for PSC-UC patients. Histopathological examination revealed persistent microscopic inflammation in 88% of PSC-UC patients with MES grade 0 (46% of all PSC-UC patients). Moreover, MES overestimated the severity of active inflammation in an additional 11% of PSC-UC patients.

MES insufficiently identifies microscopic inflammation in PSC-UC. This indicates that histological evaluation should become a routine procedure of the diagnostic and grading system in both PSC-UC and PSC.

Core Tip: Ulcerative colitis (UC) with concomitant primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC) represents a distinct disease entity (PSC-UC). Our results highlight the limitations of endoscopic examination in uncovering microscopic inflammatory lesions, resulting in the erroneous classification of PSC-UC patients as healthy. To mitigate the risk of underdiagnosis, histopathological examination should therefore be an essential component of the diagnostic approach for UC in PSC patients.

- Citation: Wohl P, Krausova A, Wohl P, Fabian O, Bajer L, Brezina J, Drastich P, Hlavaty M, Novotna P, Kahle M, Spicak J, Gregor M. Limited validity of Mayo endoscopic subscore in ulcerative colitis with concomitant primary sclerosing cholangitis. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2024; 16(11): 607-616

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v16/i11/607.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v16.i11.607

Primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC) is a chronic cholestatic liver disease characterized by progressive inflammation, fibrosis, and diffuse multiple stricturing of the intrahepatic and extrahepatic bile ducts[1]. In up to 80% of patients, PSC is closely associated with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) prevalently with a unique type of ulcerative colitis (UC) known as PSC-UC[2,3].

As a distinct clinical phenotype, PSC-UC manifests with colonoscopic features that differ from those of typical UC without hepatobiliary disease. Interestingly, PSC-UC may not develop clinically apparent gastrointestinal symptoms[4,5]. Multiple studies[2,6,7] have shown that the colonic inflammation in PSC-UC is typically more pronounced in the right-sided colon with often minimal to normal mucosal findings in the rectum. Furthermore, PSC-UC is characterized by a lower incidence of inflammatory polyps[4,8] and a higher incidence of backwash ileitis[9] when compared to UC. In up to 94% of PSC-UC cases, the phenotype is reported as pancolitis with rectal sparing. Although colitis in PSC tends to follow a quiescent course, PSC-UC is associated with a high incidence of malignancies represented mainly by colitis-associated carcinoma (CAC)[10-13]. The risk of CAC is higher in PSC-UC than in UC alone[14], which is why accurate diagnosis is important for all PSC-UC patients.

IBD diagnosis is largely based on clinical symptoms, endoscopy, and histopathology[15] with endoscopic assessment being the most feasible and reliable approach[16] in routine clinical practice. Among many different endoscopic scores for UC[17], the Mayo endoscopic subscore (MES)[18,19], a component of the Mayo Clinic Score, is recommended to assess disease activity and remains the most frequently used score in both clinical practice and clinical trials[18]. Surprisingly, despite accumulating evidence for the limited diagnostic accuracy of endoscopic techniques[20-24], namely in the context of mild mucosal inflammation, neither MES nor any of the other endoscopic scores have been validated for PSC-UC.

Endoscopy-based approaches are not sufficiently reliable for PSC-UC patients. This can lead to poor therapeutic decisions and misguided treatment. Histopathological evaluation can remedy this by detecting potential microscopic disease activity, despite the absence of clinical or endoscopic signs of disease common in PSC-UC patients[20-24]. Out of the more than 30 described UC histological scores[25], the newly established Nancy histological index (NHI)[25-27] has quickly become one of the most popular histological scoring systems of inflammatory activity in UC. In 2020, the European Crohn's and Colitis Organization recommended NHI for daily clinical practice[28].

Given the challenges of endoscopy for PSC-UC, the diagnostic relevance of MES for PSC-UC is unclear despite MES being a standard tool for assessing inflammation in UC. The overall objective of this study was: (1) To compare the reliability of MES as a diagnostic tool between UC and PSC-UC patient cohorts; and (2) To assess the accuracy of MES in PSC-UC patients using histological disease activity scoring (NHI).

This was a prospective longitudinal study performed at the Institute for Clinical and Experimental Medicine (Prague, Czech Republic), a tertiary health care center. We included 59 Caucasian adult patients diagnosed with UC (n = 29) and PSC-UC (n = 30) according to conventional diagnostic criteria, who were admitted to the Hepatogastroenterology Department for a colonoscopy from July 2016 to March 2021. As portal hypertension with portal colopathy in liver cirrhosis are common endoscopic features that may mimic some inflammatory changes typical for PSC-UC, patients with advanced liver cirrhosis with portal hypertension were excluded. Other exclusion criteria were colitis-associated cancer and colonic dysplasia. The study cohort consisted of 20 females and 39 males (sex). This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Institute for Clinical and Experimental Medicine and Thomayer Hospital with Multi-Center Competence (G16-06-25) and performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects before the study. All patients have been characterized as summarized in Table 1.

| Characteristic | UC | PSC-UC | P value |

| Patients | 29 | 30 | |

| Male sex | 16 (55) | 23 (77) | 0.10 |

| Age in years | 43.2 ± 12.5 | 37.2 ± 2.9 | 0.07 |

| Duration of disease in years | 12.9 ± 10.6 | 10.6 ± 6.9 | 0.62 |

| pANCA positive | 14 (48) | 16 (53) | 0.8 |

| Portal hypertension | 0 | 0 | |

| Cholecystectomy | 1 (3) | 1 (3) | |

| BMI in a.u. | 25.1 ± 4.1 | 23.5 ± 4.2 | 0.1 |

| Corticosteroids | 10 (34) | 10 (33) | |

| Mesalamine | 12 (41) | 20 (66) | |

| Mesalamine and immunomodulators | 12 (41) | 9 (30) | |

| Biological treatment | 5 (17) | 0 | |

| Ursodeoxycholic acid | 0 | 30 (100) | |

| Fecal calprotectin in μg/g, median (95%CI) | 478 (263–917) | 96 (60-231) | < 0.001 |

All UC and PSC-UC patients were subjected to a colonoscopy with a standard white light endoscope. During the colonoscopy, two or three biopsies from the terminal ileum, cecum, and rectum of endoscopically most severely inflamed mucosa were collected. Endoscopic disease activity was assessed using MES[18]. Histological inflammation in the colon biopsies (cecum and rectum) was assessed by NHI as published previously for UC[26]. In addition, histological inflammation in biopsies from the terminal ileum was determined by a four-grade scoring system (0-3), where 0 corresponds to normal and 3 to severe inflammation. Blinded histopathological evaluation of paraffin-embedded sections stained with hematoxylin-eosin was performed by a trained pathologist (Ondrej Fabian).

PSC was defined by the presence of intra- and/or extra-hepatic bile duct abnormalities in the form of beading, duct ectasia, and stricturing of the intra- or extra-hepatic bile ducts documented in the medical record from endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography, magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography, and/or liver biopsy. Small duct PSC was defined when there were histological features consistent with PSC on liver biopsy in the absence of characteristic radiological features. The diagnosis of PSC was also confirmed by laboratory tests (see below).

Blood analysis was performed on the day of the colonoscopy, including the determination of hemoglobin, leukocytes, platelets, and albumin (not shown). A stool sample that was obtained immediately before bowel preparation was provided by each patient for the analysis of fecal calprotectin (FC). FC level was measured by ELISA EliA kit (Phadia AB, Uppsala, Sweden). Detection of anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody and IgG4 was performed using kits from Inova Diagnostics Inc. (San Diego, CA, United States).

All ordinal variables are presented as medians with 95%CI; continuous variables are expressed as means ± standard errors. All differences between independent ordinal variables were tested by Mann-Whitney U test, differences in paired measurements were assessed by Wilcoxon signed-rank test and differences in proportions were tested by Fisher exact test. Correlations are expressed as Spearman's rank correlation coefficient (r). For comparison of MES with NHI, only the most severely affected lesion with the highest NHI grade was considered for each patient. All data were analyzed using the Python ecosystem. Statistical significance was accepted at P ≤ 0.05. The statistical methods of this study were reviewed by Michal Kahle from Department of Data Analysis, Statistics, and AI, Institute for Clinical and Experimental Medicine, Prague, Czech Republic.

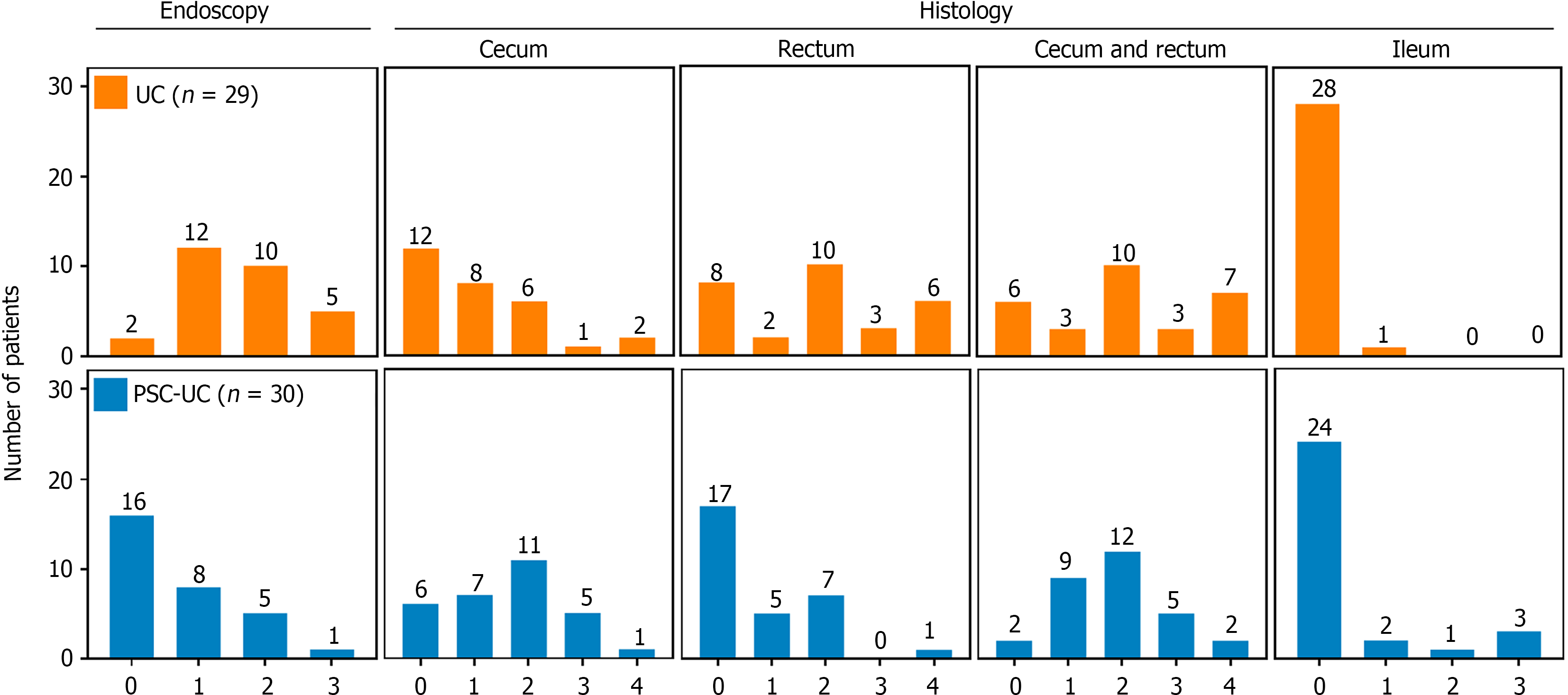

The severity of UC was assessed both endoscopically and histologically in PSC-UC (Figure 1, upper panels) and UC (Figure 1, lower panels) patients. Endoscopy and histopathology involved examination of samples from the cecum, rectum and ileum. Among UC patients, only two individuals (7%) showed normal endoscopic findings (MES grade 0); the majority exhibited mild to moderate mucosal inflammation and damage (MES grades 1 and 2; median MES grade 2; Table 2). Similarly, histopathological examination revealed that most UC patients (90%) showed normal findings or mild inflammation with median NHI grade 1 in the cecum (Table 2). However, in the rectum, 30% of UC patients exhibited a shift towards moderate to severe active inflammation (median NHI grade 2; Table 2), which aligned with the MES findings. When considering the most severely inflamed biopsy for each patient (Figure 1, "cecum and rectum" panel), a significant correlation between MES and NHI was observed in UC patients (Spearman's r = 0.40, P = 0.029).

| Parameter | PSC-UC | UC | P value |

| MES | 0 (0-1) | 2 (1-2) | < 0.001 |

| Inflammation (ileum) | 0 (0-0) | 0 (0-0) | |

| NHI (cecum) | 2 (1-2) | 1 (0-2) | 0.048 |

| NHI (rectum) | 0 (0-1) | 2 (0-3) | 0.002 |

In contrast to only two UC patients, MES identified 16 (53%) PSC-UC patients with normal endoscopic appearance (MES grade 0; median MES grade 0; Table 2). In the rectum, a similar distribution was observed with a majority (57%) of PSC-UC patients without histologically active disease (median NHI grade 0, Table 2). However, in the cecum, a more pronounced inflammatory pattern emerged, with 80% of PSC-UC patients displaying NHI grades ranging from 1 to 4 (median NHI grade 2; Table 2). This highlights a significant discrepancy between MES and NHI in PSC-UC patients, which is further corroborated by the lack of correlation between the two measures (Spearman's r = 0.27, P = 0.14). Notably, for the correlation analysis, only the grades corresponding to the most affected lesions were considered, effectively approximating the situation in the cecum (Figure 1, "cecum and rectum").

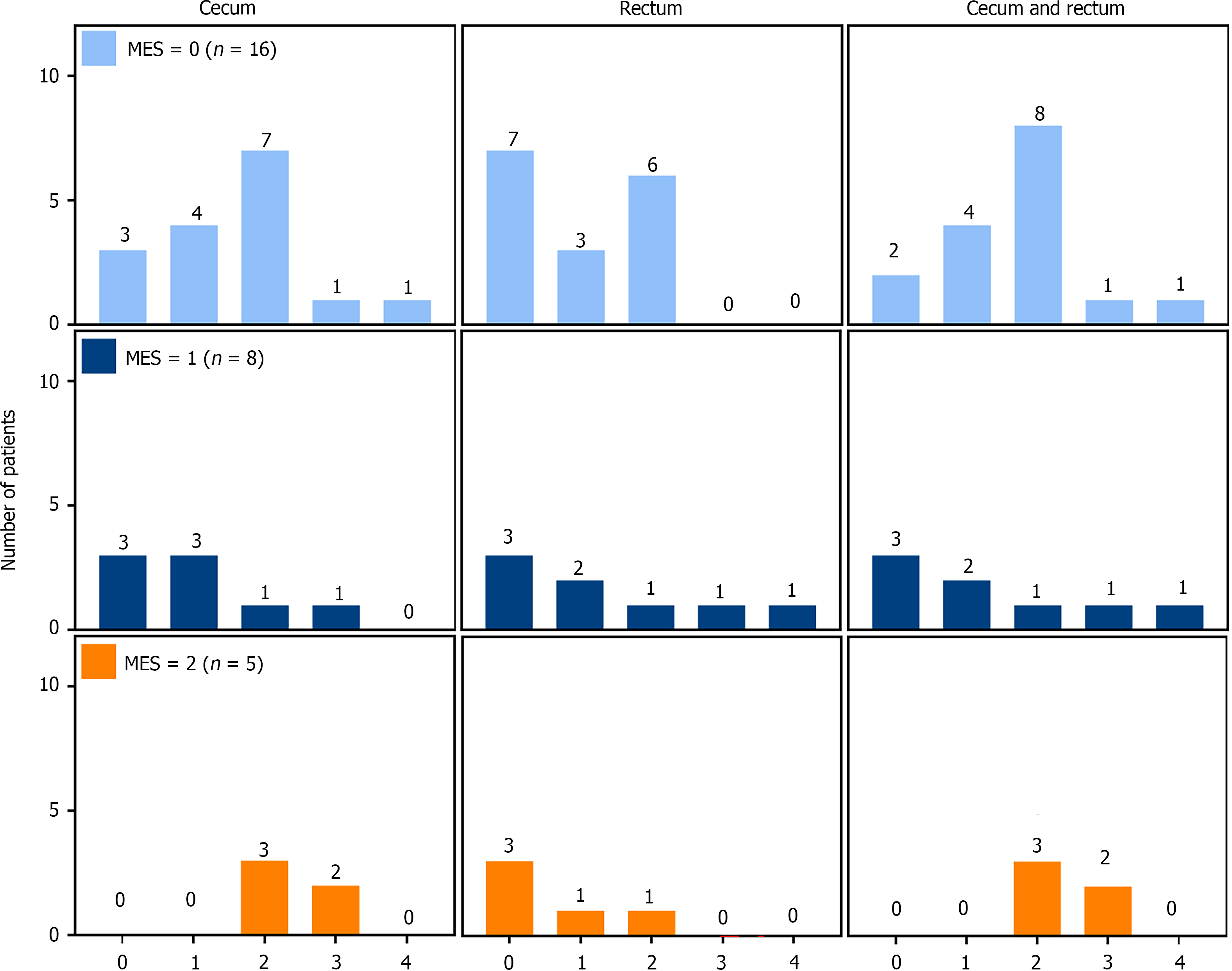

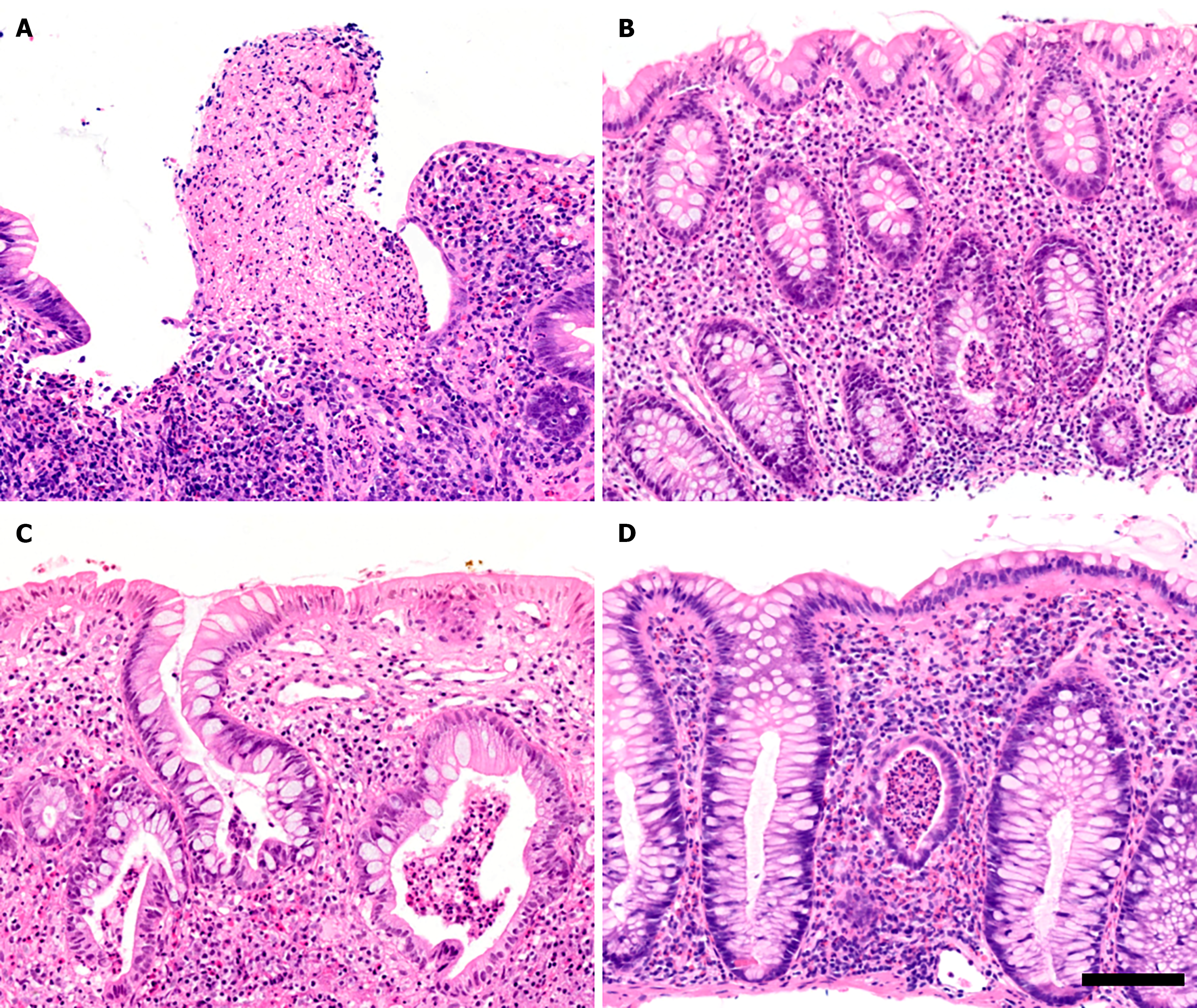

To understand the discrepancy between MES and NHI in PSC-UC patients, the NHI values of 16 PSC-UC patients with MES grade 0 were analyzed (Figure 2, upper panels). Surprisingly, this analysis revealed that 13 of these patients (81%) had NHI grades between 1 and 4 in the cecum (Figure 3A and B) and 9 (56%) had NHI grades between 1 and 4 in the rectum. When considering both the cecum and rectum for each patient, only two individuals (12.5%) had NHI grades of 0 in both segments (Figure 2, “cecum and rectum” panel). Hence, MES failed to detect active UC in 14 (88%) of the PSC-UC patients with MES grade 0, which corresponds to 46% of all PSC-UC patients.

Further analysis of the NHI scores revealed that among the eight PSC-UC patients with MES grade 1, three patients showed no signs of inflammation (NHI grade 0) while three exhibited active inflammation with NHI grades ranging from 2 to 4 (Figure 2, middle panels; Figure 3C). Similarly, among the five patients with MES grade 2, two individuals displayed active inflammation with NHI grade 3 (Figure 2, lower panels; Figure 3D). This suggests that MES incorrectly diagnosed three PSC-UC patients. Taken together, these results clearly indicate that MES insufficiently identified ongoing microscopic inflammation in 17 (57%) of PSC-UC patients, which would negatively affect therapeutic decisions.

All patients were characterized as summarized in Table 1. Of note, fecal calprotectin (FC) levels in UC patients were significantly elevated, with a median of 478 μg/g (95%CI: 263–917), compared to the widely accepted upper limit of 100 μg/g[29]. In contrast, FC levels in PSC-UC patients were within the normal range, with a median of 96 μg/g (95%CI: 60-231). This suggests that PSC-UC patients have nearly absent or very mild UC manifestation, compared to the severe manifestation in UC patients.

Histopathological examination consistently supported the notion of a more severe inflammatory pattern in the rectum of UC patients, as evidenced by the highest NHI grades (Figure 1, Table 2). In contrast, PSC-UC patients predominantly exhibited inflammatory changes in the cecum (median NHI grade 2 vs 0 in rectum; P < 0.01; Figure 1; Table 2), suggesting complete or partial rectal sparing. Indeed, 60% of PSC-UC patients had spared rectal mucosa compared to just 10% of UC patients (P < 0.001).

In addition, inflammation scoring in the ileum exhibited similar median values in both UC and PSC-UC patients (median NHI grade 0; Figure 1, Table 2). Nevertheless, 6 PSC-UC patients (20%) exhibited mild to severe inflammation (NHI grades 1-3) compared to only one patient in the UC group (3%; P = 0.047; Figure 1), thus suggesting higher incidence of backwash ileitis in PSC-UC patients. These findings collectively underscore the variability of inflammation intensity across different segments of the intestine in both PSC-UC and UC.

To date, almost 30 scoring systems have been introduced to accurately assess colitis disease severity in IBD. However, despite extensive validations, none of these systems have been universally recognized as versatile[30]. In this study, we aimed to validate the commonly used MES system for evaluating UC in PSC-UC patients and compare the results with histopathological observations expressed through the NHI. Our findings demonstrate a correlation between MES and NHI in UC patients, but a lack of correlation in PSC-UC patients (as indicated by Spearman’s r). MES fails to identify ongoing histological inflammation (NHI grade 1-4, Figure 2 and Figure 3) in more than 46% of PSC-UC patients who were assigned MES grade 0. This significant discrepancy highlights a major limitation of endoscopic assessment, which could potentially lead to an underestimation of PSC-UC severity. Therefore, we recommend the routine use of histological scoring in clinical practice to overcome this limitation.

It has been reported that UC in PSC manifests mildly or even completely without symptoms compared to typical UC[5,31]. Additionally, Murasugi et al[5] documented no correlation between the severity of liver disease and colonic inflammation expressed by MES. They concluded that it is important for colonoscopy to be routinely performed immediately following a diagnosis of PSC. However, our observations show that histopathological evaluation should always accompany colonoscopy to avoid underdiagnosis.

In our current study, NHI revealed more severe colitis in the cecum of PSC-UC patients, along with an increased occurrence of backwash ileitis and rectal sparing. These findings are consistent with previous studies that have reported a high prevalence of pancolitis in PSC-UC patients ranging from 80% to 95% with varying degrees of severity and pronounced localization in the right-sided colon[4,5,7,31]. Therefore, it is crucial to inspect all colonic segments (ileum, cecum, rectum, sigmoid, descending, transverse and ascending colon) using both colonoscopy and histopathology to obtain a comprehensive understanding of the disease presentation in PSC-UC patients.

Lobatón et al[32] previously introduced two scoring systems for assessing UC activity: the modified score (MS) and the extended modified score (EMS). The MS summarizes MES from all colonic segments, while the EMS multiplies the MS by the disease extent in centimeters. These scores are both comprehensive and valuable, particularly in comparing clinical outcomes and assessing treatment effects over time, including mucosal healing. However, they do not fully address the challenge of underestimating UC severity in PSC or PSC-UC patients, especially in those with minimal endoscopic lesions or mild disease activity. This limitation highlights the need for complementary diagnostic tools beyond endoscopy in this patient population.

Although NHI has not been previously validated for PSC-UC, it has been validated for UC[27]. Furthermore, it has shown a good correlation with other established indices such as the Geboes score and Global visual analog scale[25]. Given this correlation, we have successfully employed NHI to evaluate the microscopic disease activity in PSC-UC. Importantly, interpretation must be cautiously exercised especially in treated patients, as NHI grade 0 is assigned to both normal histological observation and mild chronic inflammation without activity.

Our study highlights the critical importance of incorporating histological evaluation into the diagnostic and grading framework for PSC and PSC-UC. Although our cohort was small (59 patients from a single center), similar findings were reported in a larger study involving 131 UC patients, which compared the MES with various histologic scores[22]. Interestingly, while a strong correlation between MES and histologic scores was found in cases of inactive or severe UC, histology proved essential for accurate assessment in patients with mild disease. MES tends to underestimate mild progression, potentially leading to suboptimal patient management.

We propose that routine endoscopy followed by histological evaluation of biopsy samples should be standard practice for all PSC patients, particularly those without UC symptoms or visible endoscopic inflammation (MES grade 0). This approach ensures more accurate follow-up and monitoring, especially regarding the risk of malignant complications. PSC-UC carries a higher oncologic risk than UC alone, making vigilant surveillance essential[14]. While endoscopy and MES scoring remain valuable tools, they lack the resolution to capture microscopic changes critical to patient care.

In recent years, artificial intelligence (AI) has made significant strides in the field of gastroenterology, particularly in the detection and classification of colorectal polyps[33]. AI has also shown high accuracy, reaching up to 93% in distinguishing between adenomatous and hyperplastic lesions[34,35]. This technology holds promise for accurately diagnosing UC in patients with PSC, especially if deep learning models are trained on images displaying characteristic PSC-UC lesions. However, because clear endoscopic lesions are frequently absent in PSC-UC patients, the applicability of AI may be limited in these cases. As a result, histopathological evaluation will remain crucial for diagnosis and management when endoscopic findings are inconclusive.

Our study highlights that the standard MES scoring system has limited capacity to assess UC activity in the context of PSC-UC. Our results prove that histological evaluation must be incorporated into the diagnostic and grading system for PSC and PSC-UC to improve clinical management of patients, particularly in terms of monitoring malignant complications and determining the need for orthotopic liver transplantation.

We thank Lenka Bruhova and Katerina Dvorakova for their excellent support. We are especially grateful to all the patients participating in this study.

| 1. | Chapman RW, Arborgh BA, Rhodes JM, Summerfield JA, Dick R, Scheuer PJ, Sherlock S. Primary sclerosing cholangitis: a review of its clinical features, cholangiography, and hepatic histology. Gut. 1980;21:870-877. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 522] [Cited by in RCA: 513] [Article Influence: 11.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Loftus EV Jr, Harewood GC, Loftus CG, Tremaine WJ, Harmsen WS, Zinsmeister AR, Jewell DA, Sandborn WJ. PSC-IBD: a unique form of inflammatory bowel disease associated with primary sclerosing cholangitis. Gut. 2005;54:91-96. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 515] [Cited by in RCA: 518] [Article Influence: 25.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Weismüller TJ, Trivedi PJ, Bergquist A, Imam M, Lenzen H, Ponsioen CY, Holm K, Gotthardt D, Färkkilä MA, Marschall HU, Thorburn D, Weersma RK, Fevery J, Mueller T, Chazouillères O, Schulze K, Lazaridis KN, Almer S, Pereira SP, Levy C, Mason A, Naess S, Bowlus CL, Floreani A, Halilbasic E, Yimam KK, Milkiewicz P, Beuers U, Huynh DK, Pares A, Manser CN, Dalekos GN, Eksteen B, Invernizzi P, Berg CP, Kirchner GI, Sarrazin C, Zimmer V, Fabris L, Braun F, Marzioni M, Juran BD, Said K, Rupp C, Jokelainen K, Benito de Valle M, Saffioti F, Cheung A, Trauner M, Schramm C, Chapman RW, Karlsen TH, Schrumpf E, Strassburg CP, Manns MP, Lindor KD, Hirschfield GM, Hansen BE, Boberg KM; International PSC Study Group. Patient Age, Sex, and Inflammatory Bowel Disease Phenotype Associate With Course of Primary Sclerosing Cholangitis. Gastroenterology. 2017;152:1975-1984.e8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 345] [Cited by in RCA: 364] [Article Influence: 45.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 4. | Jørgensen KK, Grzyb K, Lundin KE, Clausen OP, Aamodt G, Schrumpf E, Vatn MH, Boberg KM. Inflammatory bowel disease in patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis: clinical characterization in liver transplanted and nontransplanted patients. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2012;18:536-545. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 91] [Cited by in RCA: 98] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Murasugi S, Ito A, Omori T, Nakamura S, Tokushige K. Clinical Characterization of Ulcerative Colitis in Patients with Primary Sclerosing Cholangitis. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2020;2020:7969628. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Boonstra K, van Erpecum KJ, van Nieuwkerk KM, Drenth JP, Poen AC, Witteman BJ, Tuynman HA, Beuers U, Ponsioen CY. Primary sclerosing cholangitis is associated with a distinct phenotype of inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2012;18:2270-2276. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 140] [Cited by in RCA: 160] [Article Influence: 12.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | de Vries AB, Janse M, Blokzijl H, Weersma RK. Distinctive inflammatory bowel disease phenotype in primary sclerosing cholangitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:1956-1971. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 120] [Cited by in RCA: 146] [Article Influence: 14.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Mahmoud R, Shah SC, Ten Hove JR, Torres J, Mooiweer E, Castaneda D, Glass J, Elman J, Kumar A, Axelrad J, Ullman T, Colombel JF, Oldenburg B, Itzkowitz SH; Dutch Initiative on Crohn and Colitis. No Association Between Pseudopolyps and Colorectal Neoplasia in Patients With Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Gastroenterology. 2019;156:1333-1344.e3. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 9.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Loftus EV Jr, Sandborn WJ, Lindor KD, Larusso NF. Interactions between chronic liver disease and inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 1997;3:288-302. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Weismüller TJ, Wedemeyer J, Kubicka S, Strassburg CP, Manns MP. The challenges in primary sclerosing cholangitis--aetiopathogenesis, autoimmunity, management and malignancy. J Hepatol. 2008;48 Suppl 1:S38-S57. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 115] [Cited by in RCA: 109] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Sokol H, Cosnes J, Chazouilleres O, Beaugerie L, Tiret E, Poupon R, Seksik P. Disease activity and cancer risk in inflammatory bowel disease associated with primary sclerosing cholangitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:3497-3503. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Kornfeld D, Ekbom A, Ihre T. Is there an excess risk for colorectal cancer in patients with ulcerative colitis and concomitant primary sclerosing cholangitis? A population based study. Gut. 1997;41:522-525. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 176] [Cited by in RCA: 160] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Broomé U, Löfberg R, Veress B, Eriksson LS. Primary sclerosing cholangitis and ulcerative colitis: evidence for increased neoplastic potential. Hepatology. 1995;22:1404-1408. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Fung BM, Lindor KD, Tabibian JH. Cancer risk in primary sclerosing cholangitis: Epidemiology, prevention, and surveillance strategies. World J Gastroenterol. 2019;25:659-671. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 88] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 11.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 15. | Maaser C, Sturm A, Vavricka SR, Kucharzik T, Fiorino G, Annese V, Calabrese E, Baumgart DC, Bettenworth D, Borralho Nunes P, Burisch J, Castiglione F, Eliakim R, Ellul P, González-Lama Y, Gordon H, Halligan S, Katsanos K, Kopylov U, Kotze PG, Krustinš E, Laghi A, Limdi JK, Rieder F, Rimola J, Taylor SA, Tolan D, van Rheenen P, Verstockt B, Stoker J; European Crohn’s and Colitis Organisation [ECCO] and the European Society of Gastrointestinal and Abdominal Radiology [ESGAR]. ECCO-ESGAR Guideline for Diagnostic Assessment in IBD Part 1: Initial diagnosis, monitoring of known IBD, detection of complications. J Crohns Colitis. 2019;13:144-164. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1242] [Cited by in RCA: 1161] [Article Influence: 193.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Bouguen G, Levesque BG, Pola S, Evans E, Sandborn WJ. Feasibility of endoscopic assessment and treating to target to achieve mucosal healing in ulcerative colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2014;20:231-239. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | D'Haens G, Sandborn WJ, Feagan BG, Geboes K, Hanauer SB, Irvine EJ, Lémann M, Marteau P, Rutgeerts P, Schölmerich J, Sutherland LR. A review of activity indices and efficacy end points for clinical trials of medical therapy in adults with ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:763-786. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 722] [Cited by in RCA: 795] [Article Influence: 44.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 18. | Schroeder KW, Tremaine WJ, Ilstrup DM. Coated oral 5-aminosalicylic acid therapy for mildly to moderately active ulcerative colitis. A randomized study. N Engl J Med. 1987;317:1625-1629. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1958] [Cited by in RCA: 2250] [Article Influence: 59.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Sandborn WJ, Feagan BG, Hanauer SB, Lochs H, Löfberg R, Modigliani R, Present DH, Rutgeerts P, Schölmerich J, Stange EF, Sutherland LR. A review of activity indices and efficacy endpoints for clinical trials of medical therapy in adults with Crohn's disease. Gastroenterology. 2002;122:512-530. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 491] [Cited by in RCA: 504] [Article Influence: 21.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Park S, Abdi T, Gentry M, Laine L. Histological Disease Activity as a Predictor of Clinical Relapse Among Patients With Ulcerative Colitis: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2016;111:1692-1701. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 177] [Cited by in RCA: 155] [Article Influence: 17.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Ozaki R, Kobayashi T, Okabayashi S, Nakano M, Morinaga S, Hara A, Ohbu M, Matsuoka K, Toyonaga T, Saito E, Hisamatsu T, Hibi T. Histological Risk Factors to Predict Clinical Relapse in Ulcerative Colitis With Endoscopically Normal Mucosa. J Crohns Colitis. 2018;12:1288-1294. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Lemmens B, Arijs I, Van Assche G, Sagaert X, Geboes K, Ferrante M, Rutgeerts P, Vermeire S, De Hertogh G. Correlation between the endoscopic and histologic score in assessing the activity of ulcerative colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2013;19:1194-1201. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 94] [Cited by in RCA: 110] [Article Influence: 9.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Bryant RV, Burger DC, Delo J, Walsh AJ, Thomas S, von Herbay A, Buchel OC, White L, Brain O, Keshav S, Warren BF, Travis SP. Beyond endoscopic mucosal healing in UC: histological remission better predicts corticosteroid use and hospitalisation over 6 years of follow-up. Gut. 2016;65:408-414. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 240] [Cited by in RCA: 317] [Article Influence: 35.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Zenlea T, Yee EU, Rosenberg L, Boyle M, Nanda KS, Wolf JL, Falchuk KR, Cheifetz AS, Goldsmith JD, Moss AC. Histology Grade Is Independently Associated With Relapse Risk in Patients With Ulcerative Colitis in Clinical Remission: A Prospective Study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2016;111:685-690. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 138] [Cited by in RCA: 135] [Article Influence: 15.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Mosli MH, Parker CE, Nelson SA, Baker KA, MacDonald JK, Zou GY, Feagan BG, Khanna R, Levesque BG, Jairath V. Histologic scoring indices for evaluation of disease activity in ulcerative colitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;5:CD011256. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Marchal-Bressenot A, Salleron J, Boulagnon-Rombi C, Bastien C, Cahn V, Cadiot G, Diebold MD, Danese S, Reinisch W, Schreiber S, Travis S, Peyrin-Biroulet L. Development and validation of the Nancy histological index for UC. Gut. 2017;66:43-49. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 218] [Cited by in RCA: 323] [Article Influence: 40.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Marchal-Bressenot A, Scherl A, Salleron J, Peyrin-Biroulet L. A practical guide to assess the Nancy histological index for UC. Gut. 2016;65:1919-1920. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Magro F, Doherty G, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Svrcek M, Borralho P, Walsh A, Carneiro F, Rosini F, de Hertogh G, Biedermann L, Pouillon L, Scharl M, Tripathi M, Danese S, Villanacci V, Feakins R. ECCO Position Paper: Harmonization of the Approach to Ulcerative Colitis Histopathology. J Crohns Colitis. 2020;14:1503-1511. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 126] [Article Influence: 25.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Bjarnason I. The Use of Fecal Calprotectin in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y). 2017;13:53-56. [PubMed] |

| 30. | Mohammed Vashist N, Samaan M, Mosli MH, Parker CE, MacDonald JK, Nelson SA, Zou GY, Feagan BG, Khanna R, Jairath V. Endoscopic scoring indices for evaluation of disease activity in ulcerative colitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;1:CD011450. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 88] [Article Influence: 12.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Palmela C, Peerani F, Castaneda D, Torres J, Itzkowitz SH. Inflammatory Bowel Disease and Primary Sclerosing Cholangitis: A Review of the Phenotype and Associated Specific Features. Gut Liver. 2018;12:17-29. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 116] [Article Influence: 16.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Lobatón T, Bessissow T, De Hertogh G, Lemmens B, Maedler C, Van Assche G, Vermeire S, Bisschops R, Rutgeerts P, Bitton A, Afif W, Marcus V, Ferrante M. The Modified Mayo Endoscopic Score (MMES): A New Index for the Assessment of Extension and Severity of Endoscopic Activity in Ulcerative Colitis Patients. J Crohns Colitis. 2015;9:846-852. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 119] [Article Influence: 11.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Ozawa T, Ishihara S, Fujishiro M, Kumagai Y, Shichijo S, Tada T. Automated endoscopic detection and classification of colorectal polyps using convolutional neural networks. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2020;13:1756284820910659. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 105] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 15.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | van Bokhorst QNE, Houwen BBSL, Hazewinkel Y, Fockens P, Dekker E. Advances in artificial intelligence and computer science for computer-aided diagnosis of colorectal polyps: current status. Endosc Int Open. 2023;11:E752-E767. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Yang YJ, Cho BJ, Lee MJ, Kim JH, Lim H, Bang CS, Jeong HM, Hong JT, Baik GH. Automated Classification of Colorectal Neoplasms in White-Light Colonoscopy Images via Deep Learning. J Clin Med. 2020;9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |