Published online Aug 16, 2023. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v15.i8.518

Peer-review started: March 21, 2023

First decision: April 21, 2023

Revised: May 22, 2023

Accepted: July 6, 2023

Article in press: July 6, 2023

Published online: August 16, 2023

Processing time: 142 Days and 0.2 Hours

Dental injury is the leading cause of litigation in anaesthesia but an underrecognized preventable complication of endoscopy.

To determine frequency and effects of dental injury in endoscopy, we present findings from an audit of outpatient endoscopy procedures conducted at a tertiary university hospital and a systematic review of literature.

Retrospective review of 11265 outpatient upper endoscopy procedures over the period of 1 June 2019 to 31 May 2021 identified dental related complications in 0.284% of procedures. Review of literature identified a similar rate of 0.33%.

Pre-existing dental pathology or the presence of prostheses makes damage more likely but sound teeth may be affected. Pre-endoscopic history and tooth exami

Dental complications occur in approximately 1 in 300 of upper endoscopy cases. These are easily preventable by pre-endoscopy screening. Protocols to mitigate dental injury are also suggested.

Core Tip: Peri-intubation dental injury is a leading cause of litigation in endoscopy, and its complications are largely prevented with sufficient foreknowledge and counselling. We summarize findings from an audit of dental injury on endoscopy as well as review relevant literature to guide identification, mitigation and management of peri-endoscopic dental trauma.

- Citation: Tan CQL, Loh GYW, Benjamin TWR, Koh CJ, Mok JSR, Hartono JL, Chua KTC, Tan HH, Siah KTH. Dental trauma in endoscopy: A systematic review and experience of a tertiary endoscopy centre. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2023; 15(8): 518-527

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v15/i8/518.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v15.i8.518

Peri-intubation dental injury is a leading cause of litigation in anaesthesia[1] with incidence of between 0.02%-0.07%[2-5]. Endoscopic procedures such as Oesophagogastroduodenoscopy (OGD), Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS), endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) and Bronchoscopy likewise involve per-oral intubation and face similar complications. This subject has been under-represented in the field of endoscopy and is a cause for concern[6]. Dental complications are largely prevented with sufficient foreknowledge and counselling. We hence aim to study the impact of dental injury on endoscopy in our centre as well as review relevant literature to guide identification, mitigation and management of peri-endoscopic dental trauma.

We reviewed outpatient endoscopy records over a two-year period at the National University Hospital, Singapore. This was a large university hospital system that included community referrals and tertiary care centres across multiple specialties. According to centre protocol, dentition is reviewed once by the nursing team at triage and subsequently by the procedural team prior to endoscopy. Upper endoscopy is cancelled should dental concerns be identified. Cancelled endoscopies and serious reportable events due to dental reasons were compiled into a database for analysis.

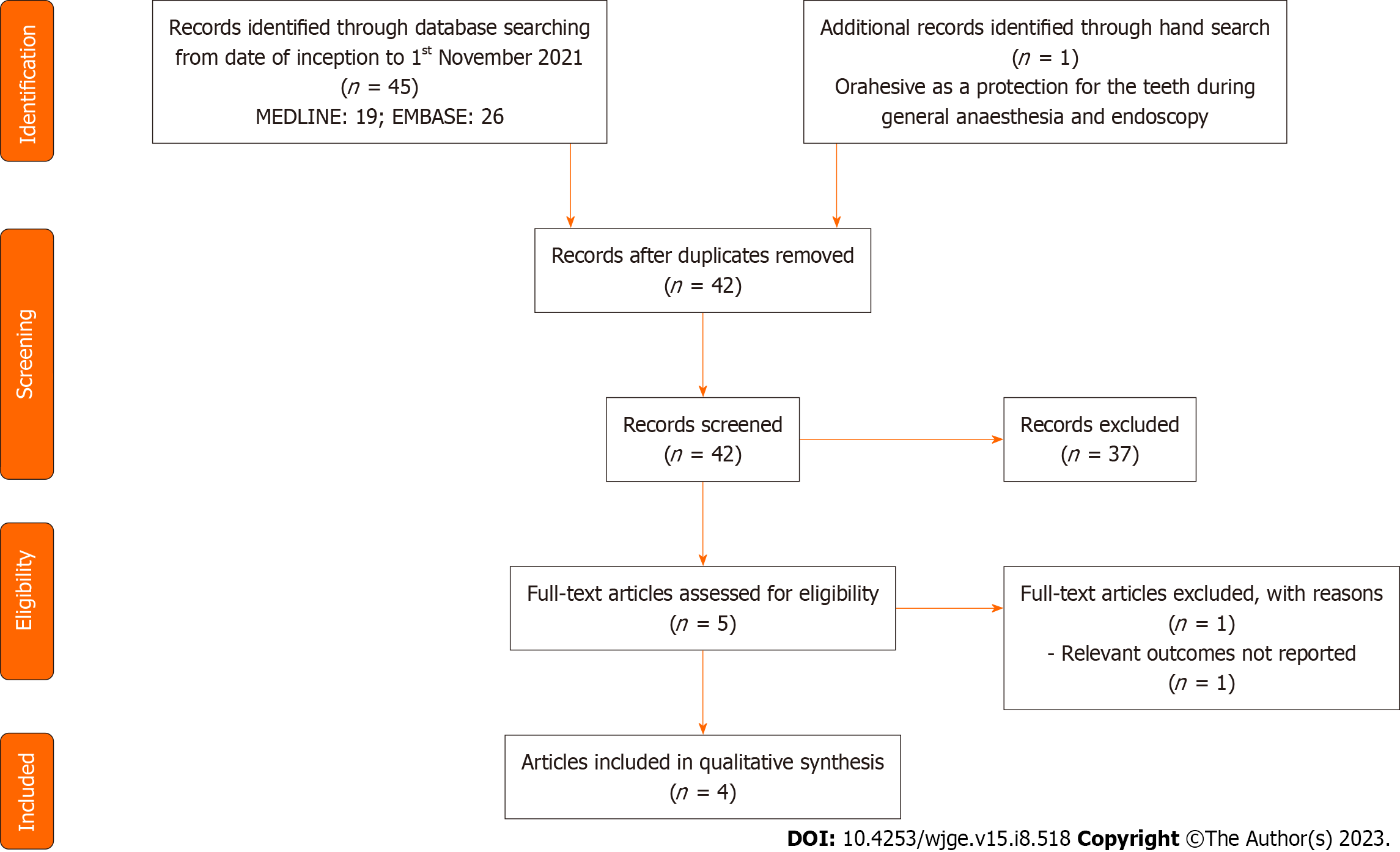

The review was conducted with reference to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses[7-11]. The PRISMA flowchart demonstrating the study selection process is presented in Figure 1. A systematic search was conducted on Medline using the following Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms: (("Tooth Injuries"[Mesh]) OR ("Mouth Protectors"[Mesh])) AND ((("Bronchoscopy"[Mesh]) OR "Endoscopy, Digestive System"[Mesh])) and EMBASE using the following EMTREE subject headings: ('digestive tract endoscopy'/exp OR 'bronchoscopy'/exp) AND ('tooth injury'/exp OR 'mouth protector'/exp). We additionally searched websites and conference abstracts for unpublished, updated reports on dental trauma in endoscopy and mitigation measures. Only English articles involving human subjects published prior to 1 November 2021 were considered for inclusion. Two independent reviewers (BT, CTQL) performed a systematic search, evaluated the titles and abstracts, and selected relevant studies with any discrepancies resolved by a third independent reviewer (LYWG). 46 articles were retrieved from the initial search strategy with 42 remaining after duplicate removal. A total of four publications involving dental trauma in relation to gastrointestinal and bronchial endoscopy were identified using this methodology (see Table 1). Major adverse events were characterized as cases of tooth fracture, tooth avulsion, tooth subluxation while minor adverse events encompassed all other complications including gum discomfort, masticatory pain, toothache, and cancellations due to dental reasons.

| Ref. | Type | Description | n | Dental events |

| Evers et al[8], 1967 | Cohort study | Adverse dental events in cohort of patients having orahesive applied prior to endoscopy or general anaesthesia | 110 | No adverse dental events reported |

| Ackerman et al | Cohort study | Observational study on adverse dental events following upper endoscopy over 3 years | 5000 | Major adverse eventsa: 2; No minor adverse eventsb studied |

| Min et al[10], 2008 | RCT | Dental related complications following use of TPM and MB-142 mouth guards assessed via structured questionnaire 3-4 after index upper endoscopy | 865 | Major adverse events: 2; Minor adverse events: 19 |

| Mogrovejo et al[11], 2015 | Case series | Report on 3 cases of dental injury sustained after upper endoscopy | ||

From 1 June 2019 to 31 May 2021 a total of 16961 outpatients registered for endoscopy with 4643 patients undergoing multiple procedures in one setting for a total of 21539 procedures. Of which, 11265 involved upper endoscopies which was defined by any procedure involving insertion of a scope per-orally (see Table 2).

| Type | No. |

| Oesophagogastroduodenoscopy/antegrade enteroscopy | 10142 |

| Colonoscopy/sigmoidoscopy | 10263 |

| Endoscopic ultrasound | 423 |

| Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography | 248 |

| Bronchoscopy | 452 |

| Others (e.g., thoracoscopy) | 11 |

| Total number of upper endoscopy cases | 11265 |

| Total number of cases | 21539 |

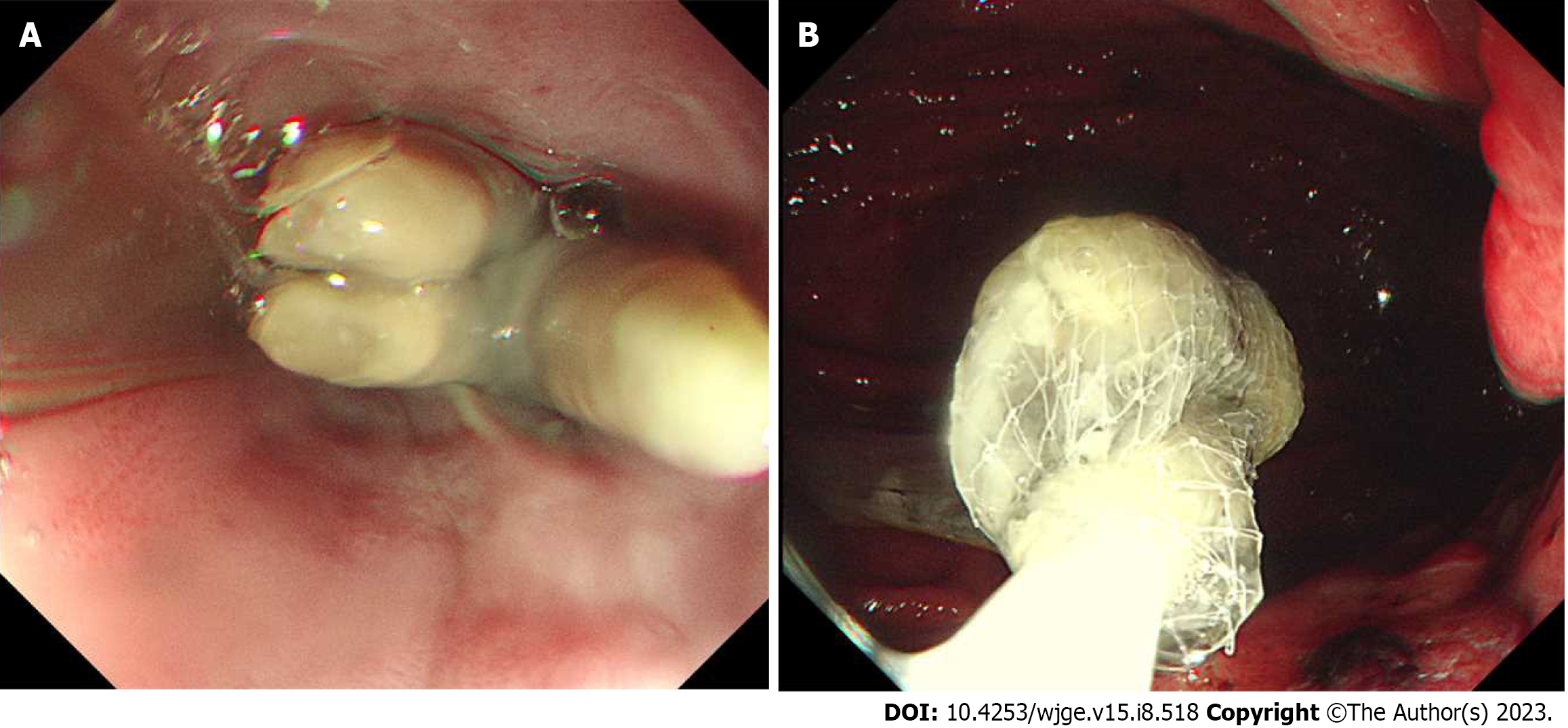

There was a total of 32 cancellations over the study period, 30 for Oesophagogastroduodenoscopy/antegrade enteroscopy and 2 for EUS (see Table 3). Of these cases, there were 6 patients requiring tooth extraction and the other 26 required dental specialist review. There was one major adverse event involving dislodgement of a glued incisor tooth chip lost during gastroscopy where judicial proceedings were avoided following prompt dental review and waiver of treatment fees. A photograph of a dislodged tooth extracted by endoscopy can be found below in Figure 2.

| Cancellations | 32 |

| Oesophagogastroduodenoscopy | 30 |

| Endoscopic ultrasound | 2 |

| Dental injury | 1 |

Our study reported a total of 32 cancellations out of the 11265 upper endoscopy cases, giving an overall of 0.284% or 1 out of 352 patients. 1 to 2 cases had to be cancelled and rearranged per month resulting in substantial logistical burden over time. Of these cancellations, at least 6 may have resulted in tooth avulsion if allowed to proceed. Pooling our findings with results obtained from the systematic review, this identified an overall adverse event rate of 0.33% with major adverse events occurring in 0.03% of upper endoscopies (see Table 4). These figures are comparable to anaesthesia data and suggest need for greater awareness of dental trauma as a complication of upper endoscopy and consequent steps for mitigation and management[12].

Teeth are subjected to immense loads generated during mastication with forces exerted exceeding 800N during strenuous clenching[13]. Dental damage may occur during instrumentation, insertion of bite-block, due to inadequate pressure distribution or slippage of the bite-block during upper endoscopy[8,14]. There has been a report of dental implant dislodgement from reflexive jaw clenching upon retroflexion during colonoscopy[15]. Dental injury may further be contributed by involuntary grinding of teeth during sedation which exerts significant pressures. These factors may chip, break or avulse a tooth as well as damage brittle prosthetic devices.

To our knowledge, there have been no studies identifying teeth most likely to be injured during endoscopy. Extrapolating from anaesthesia procedures which similarly require instrumentation within the oral cavity, the incisors are the most commonly injured representing 50% of cases[16]. They are particularly prone to fracture due to their anatomical position as well as being small-rooted and having a narrow cross-sectional area with a slight anterior axis. The most commonly reported dental injuries included enamel fractures, loosened or subluxated teeth, tooth avulsion and crown or root fractures[3].

The most significant risk factor for dental injury is pre-existing pathology such as caries, periodontitis and tooth restorations, the presence of which conveys a 3 to 12-fold increased risk[4,17,18]. Injury is most common in patients aged between 50 and 70 years who are more likely to have teeth weakened by periodontal disease while remaining dentulous[1]. Presence of restorative treatments raises the potential of damaged prosthesis and underlying periodontal disease. Removal of tooth matter during the process of restoration unavoidably weakens tooth structure and renders restored teeth prone to injury[19-21]. A non-exhaustive list of restorative and reconstructive dental treatments is included below in Table 5.

| Type of treatment | Description and related problems |

| Direct restoration (filled in single procedure with material being placed, adapted and shaped by clinician) | |

| Filling | May comprise amalgam, ceramic or precious metals. Susceptible to expansion or shrinkage when setting, which might cause tooth fracture or further decay |

| Indirect restoration (filling created outside of mouth, either from impression or digital scan of tooth) | |

| Inlays/onlays | An inlay is a filling made outside the mouth, then bonded to the teeth. This is less prone to expansion or shrinkage. An onlay refers to an inlay which covers a dental cusp |

| Crown | An onlay which fully covers the tooth which is required in the setting of marked tooth damage |

| Veneer | A thin layer bonded to the tooth surface to enhance appearance of fractured or discoloured teeth |

| Prosthesis | |

| Bridge | Fixed partial denture secured to adjacent teeth |

| Denture | Removable prosthesis which may be attached to remnant teeth via clasps |

| Implant | Permanent prosthesis integrated into alveolar bone via screws and cement. Eventual recession of gingiva may result in implant weakening |

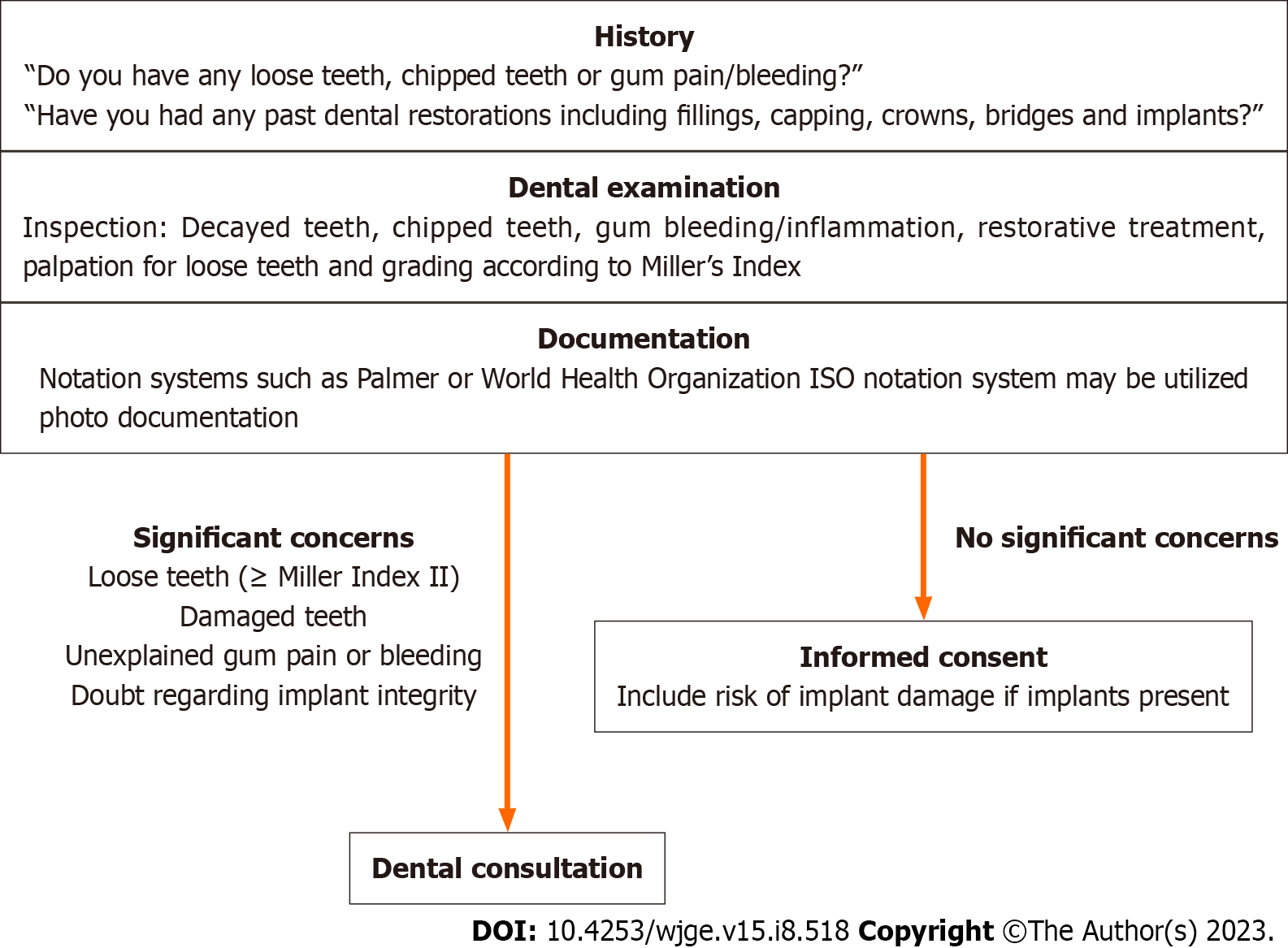

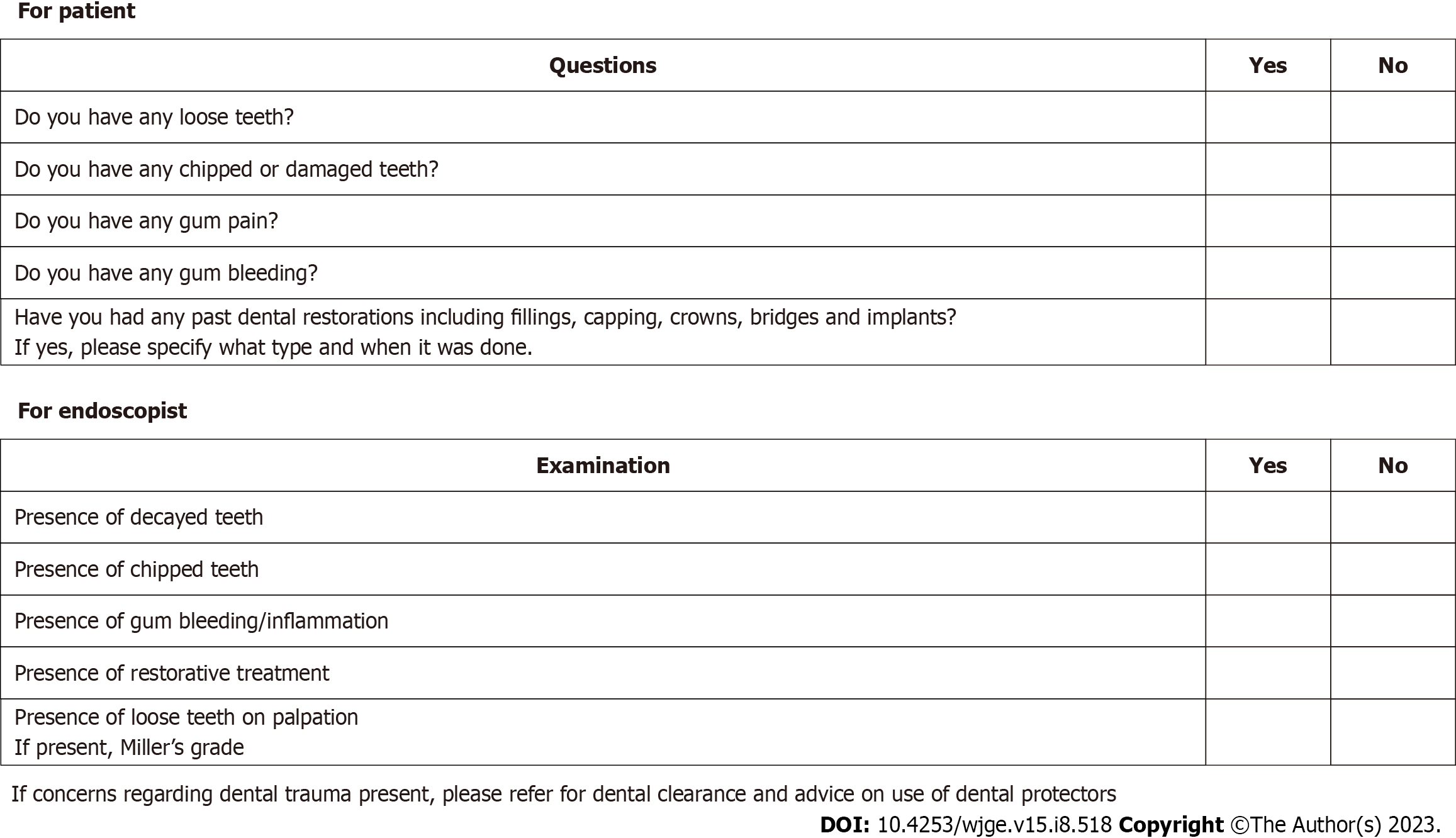

Preventing dental trauma begins with recognizing risk factors. Patients with identified concerns should be advised for dental optimization prior to endoscopy which can minimize procedural trauma by restoring caries, replacing damaged restorations, and splinting or extraction of loose teeth[22]. History and examination are paramount in this regard, and should be routinely included prior to all upper endoscopies[16,23]. Assessment should include asking patients about loose or damaged teeth and history of past restorative dental treatments. Examination of dentition involves inspection for diseased dentition and palpation for loose teeth. Tooth mobility may be evaluated clinically by applying firm pressure with a gloved finger and is reliably graded according to the Millers Index (see Table 6)[24]. A Miller’s grade of two and above suggests need for tooth extraction and warrants dental consultation[25].

| Grade | Description |

| 0 | “Physiological” mobility measured at the crown level. The tooth is mobile within the alveolus to approximately 0.1-0.2mm in a horizontal direction |

| 1 | Increased mobility of the crown of the tooth to at the most 1 mm in a horizontal direction |

| 2 | Visually increased mobility of the crown of the tooth exceeding 1 mm in a horizontal direction |

| 3 | Severe mobility of the crown of the tooth in both horizontal and vertical directions impinging on the function of the tooth |

Documentation of findings improves pre-procedural provision of information to patients and may reduce liability in the event of injury. Notation systems such as the Palmer and World Health Organization ISO system[26,27] may increase precision in documentation but may require more time and training for completion. Photo documentation is increasingly valuable for records of preprocedural tooth condition and may be considered with appropriate consent.

We propose the following framework for pre-endoscopy screening involving two questions followed by a physical examination. A screening form (Figures 3 and 4) may be conducted within five minutes and does not require specialist training.

Dental injuries often require time-sensitive management to minimize irreversible dentition loss. In all cases, the nature of the injury and the circumstances in which it occurred must be clearly documented in the patient record and full disclosure should be provided to the patient[28,29].

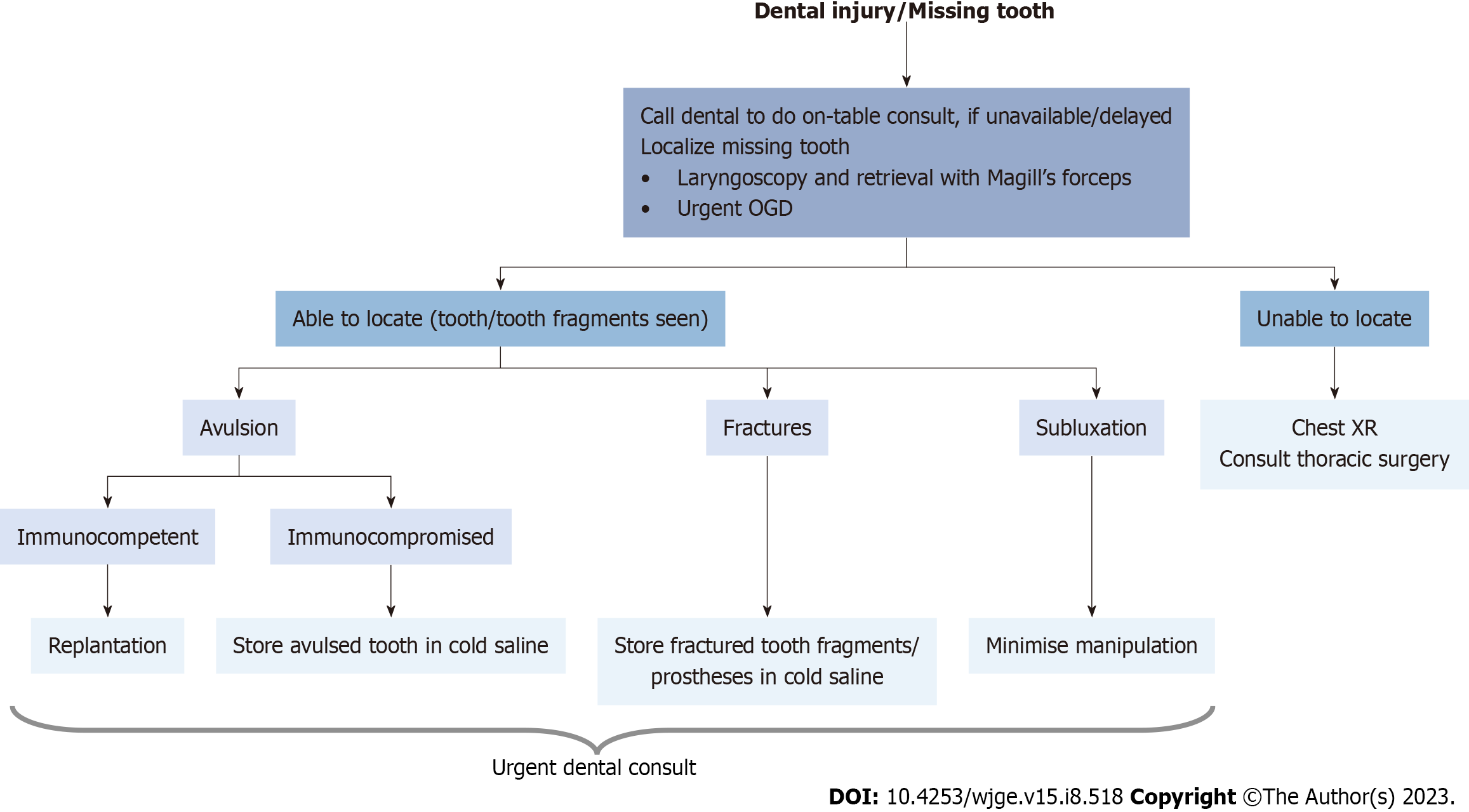

When dental trauma is suspected, the first step would be review of preprocedural dental records to ensure the injury was not present to begin with[16]. Once iatrogenic trauma is confirmed, it is essential to localize avulsed and broken teeth, or prostheses to minimise risk of aspiration and obstruction of airway. Retrieval of avulsed teeth, prostheses, or teeth fragments using Magill’s forceps may be attempted. If these measures are not successful, imaging in the form of cervical and thoracic radiography should be performed to identify aspiration into the lungs or oesophagus. Not all dental prostheses are radiopaque, and thus are difficult to visualize on a chest radiograph and may require direct visualisation in the form of urgent bronchoscopy or OGD[18]. Early consultation with thoracic surgical services is suggested in this event. A stepwise workflow to manage dental injury has been illustrated in Figure 5.

In most situations, replantation by pushing the tooth into its socket followed by firm pressure for several minutes is the immediate treatment of choice. This may not be appropriate in immunocompromised patients or those with severe periodontal disease due to the risk of bacterial seeding. If replantation is not possible, recovered teeth and teeth fragments should be placed in a suitable storage medium such as cold saline or milk and urgent dental review within 30 minutes should be arranged[18,22].

Use of tooth protectors and mouth guards have been proposed to minimize dental injuries[15,30-32]. These function by dispersing force applied among the teeth to minimize overloading a damaged tooth. Teeth protectors also serve to stabilise loose teeth and secure avulsed or broken dental fragments during trauma, thus minimising aspiration and facilitating retrieval. However, such guards often limit the amount of space for insertion of bite-blocks and instrumentation[33]. One randomized controlled trial suggested that a novel teeth-protecting mouth piece showed advantage over traditional devices in preventing endoscopy related complications of the teeth and temporomandibular joint, though this is not widely available[10]. More prospective well-designed trials supporting routine usage of dental protective devices are required prior to utilization.

In the event emergent endoscopy is required before dental consultation may be obtained, temporizing measures such as splinting loose teeth to adjacent healthy dentition or securing them via a chord affixed outside the oral cavity may be considered. All these measures should be accompanied by informed consent.

Nevertheless, several limitations need to be considered in the interpretation of our findings. Firstly, this was a retrospective audit with heterogeneity across study subjects, in terms of examination methods and baseline dental health of each patient. Secondly, there was limited availability of data with regards to pre-existing trismus which may potentially be a risk factor for dental trauma. Lastly, the adverse event rate was small, with only one instance of dental injury, suggesting need for further studies with larger sample size.

Dental injury during endoscopy is an underreported complication with potential for significant litigious consequences. It is a preventable complication with adequate foreknowledge and precautionary measures. Prompt recognition and treatment in the event of trauma can potentially minimize irreversible loss of dentition.

We present findings from an audit of outpatient endoscopy procedures conducted at a tertiary university hospital and a systematic review of literature.

Dental injury is the leading cause of litigation in anaesthesia but an underrecognized preventable complication of endoscopy.

We aim to study the impact of dental injury on endoscopy in our centre as well as review relevant literature to guide identification, mitigation and management of peri-endoscopic dental trauma.

We reviewed outpatient endoscopy records over a two-year period at the National University Hospital, Singapore. We also conducted a review with reference to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses.

We identified overall adverse event rate of 0.33% with major adverse events occurring in 0.03% of upper endoscopies. These figures are comparable to anaesthesia data and suggest need for greater awareness of dental trauma as a complication of upper endoscopy and consequent steps for mitigation and management. We identified different risk factors for dental injury and proposed a framework for pre-endoscopy screening to prevent dental injury. We also discuss measures to manage and minimise dental injury.

Dental injury during endoscopy is an underreported complication with potential for significant litigious consequences. It is a preventable complication with adequate foreknowledge and precautionary measures. Prompt recognition and treatment in the event of trauma can potentially minimize irreversible loss of dentition.

Further research can be done with larger sample sizes, to compare different risk factors for dental trauma.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: Singapore

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Liu L, China; Moshref L, Saudi Arabia; Vyawahare MA, India S-Editor: Ma YJ L-Editor: A P-Editor: Ju JL

| 1. | Givol N, Gershtansky Y, Halamish-Shani T, Taicher S, Perel A, Segal E. Perianesthetic dental injuries: analysis of incident reports. J Clin Anesth. 2004;16:173-176. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Wang LP, Hägerdal M. Reported anaesthetic complications during an 11-year period. A retrospective study. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 1992;36:234-240. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Newland MC, Ellis SJ, Peters KR, Simonson JA, Durham TM, Ullrich FA, Tinker JH. Dental injury associated with anesthesia: a report of 161,687 anesthetics given over 14 years. J Clin Anesth. 2007;19:339-345. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 93] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Tan Y, Loganathan N, Thinn KK, Liu EHC, Loh NW. Dental injury in anaesthesia: a tertiary hospital's experience. BMC Anesthesiol. 2018;18:108. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Chadwick RG, Lindsay SM. Dental injuries during general anaesthesia. Br Dent J. 1996;180:255-258. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | ASGE Standards of Practice Committee; Ben-Menachem T, Decker GA, Early DS, Evans J, Fanelli RD, Fisher DA, Fisher L, Fukami N, Hwang JH, Ikenberry SO, Jain R, Jue TL, Khan KM, Krinsky ML, Malpas PM, Maple JT, Sharaf RN, Dominitz JA, Cash BD. Adverse events of upper GI endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;76:707-718. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 204] [Cited by in RCA: 249] [Article Influence: 19.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 7. | Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, Shamseer L, Tetzlaff JM, Akl EA, Brennan SE, Chou R, Glanville J, Grimshaw JM, Hróbjartsson A, Lalu MM, Li T, Loder EW, Mayo-Wilson E, McDonald S, McGuinness LA, Stewart LA, Thomas J, Tricco AC, Welch VA, Whiting P, Moher D. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Syst Rev. 2021;10:89. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2603] [Cited by in RCA: 4399] [Article Influence: 1099.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (33)] |

| 8. | Evers W, Racz GB, Glazer J, Dobkin AB. Orahesive as a protection for the teeth during general anaesthesia and endoscopy. Can Anaesth Soc J. 1967;14:123-128. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Ackerman Z, Eliakim R. Dental injury during upper gastrointestinal endoscopy. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1996;23:72. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Min BH, Lee H, Jeong JS, Son HJ, Kim JJ, Rhee JC, Rhee PL, Yoon YB. Comparison of a novel teeth-protecting mouthpiece with a traditional device in preventing endoscopy-related complications involving teeth or temporomandibular joint: a multicenter randomized trial. Endoscopy. 2008;40:472-477. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Mogrovejo E, Gjeorgjievski M, Cappell MS. Dental Injuries From EGD: Report of Three Cases and Literature Review: 490. Official journal of the American College of Gastroenterology | ACG. 2015;110:S212. |

| 12. | Vallejo MC, Best MW, Phelps AL, O'Donnell JM, Sah N, Kidwell RP, Williams JP. Perioperative dental injury at a tertiary care health system: An eight-year audit of 816,690 anesthetics. J Healthc Risk Manag. 2012;31:25-32. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | van Eijden TM. Three-dimensional analyses of human bite-force magnitude and moment. Arch Oral Biol. 1991;36:535-539. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 112] [Cited by in RCA: 100] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Bradish T, Kaushal S, Shakeel M, Ahmad Z. Protecting teeth and gums during rigid endoscopy of the upper aerodigestive tract: Our experience with a disposable, mouldable and rigid thermoplastic mouthguard. Heighpubs Otolaryngol Rhinol. 2020;4:18-20. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 15. | Parker JD. Dental damage from a bite block during endoscopy. Ambulatory Surgery. 2020;26:63. |

| 16. | Owen H, Waddell-Smith I. Dental trauma associated with anaesthesia. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2000;28:133-145. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Bory EN, Goudard V, Magnin C. [Tooth injuries during general anesthesia, oral endoscopy and vibro-massage]. Actual Odontostomatol (Paris). 1991;45:107-120. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Abeysundara L, Creedon A, Soltanifar D. Dental knowledge for anaesthetists. BJA Education. 2016;16:362-368. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Rosenberg MB. Anesthesia-induced dental injury. Int Anesthesiol Clin. 1989;27:120-125. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Chen JJ, Susetio L, Chao CC. Oral complications associated with endotracheal general anesthesia. Ma zui Xue Za zhi. 1990;28:163-169. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Bhuva B, Giovarruscio M, Rahim N, Bitter K, Mannocci F. The restoration of root filled teeth: a review of the clinical literature. Int Endod J. 2021;54:509-535. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 17.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Mullick P, Kumar A, Prakash S. Perianesthetic dental considerations. J Anaesthesiol Clin Pharmacol. 2017;33:397-398. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Batra H, Yarmus L. Indications and complications of rigid bronchoscopy. Expert Rev Respir Med. 2018;12:509-520. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Miller SC. Textbook of Periodontia. 1st ed. Blakiston Co; 1938. |

| 25. | Laster L, Laudenbach KW, Stoller NH. An evaluation of clinical tooth mobility measurements. J Periodontol. 1975;46:603-607. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 110] [Cited by in RCA: 125] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | The International Organization for Standardization 3950:2016(en). Dentistry — Designation system for teeth and areas of the oral cavity. (Accessed November 5, 2021) Available from: https://www.iso.org/obp/ui/#iso:std:iso:3950:ed-4:v1:en. |

| 27. | Palmer C. Palmer’s Dental Notation. In: Dent Cosmos 1891; 33: 194-198. |

| 28. | Sahni V. Dental considerations in anaesthesia. JRSM Open. 2016;7:2054270416675082. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Loh Yi Wen G, Tan Qiu Lin C, Tay Wei Rong B, Mok J, Koh Jianyi C, Juanda L, Ho Siah T. IDDF2021-ABS-0144 Dental injury during endoscopy: an underrecognized teething safety issue. Gut. 2021;70 (Suppl 2):A133-A133. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 30. | Skeie A, Schwartz O. Traumatic injuries of the teeth in connection with general anaesthesia and the effect of use of mouthguards. Endod Dent Traumatol. 1999;15:33-36. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Monaca E, Fock N, Doehn M, Winterhalter M, Wappler F. [Intubation-linked dental injuries. Relevance of individually adaptable tooth protection models]. Anaesthesist. 2010;59:319-326. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Domanski M, Lee P, Sadeghi N. Cost-effective dental protection during rigid endoscopy. Laryngoscope. 2011;121:2590-2591. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Vogel J, Stübinger S, Kaufmann M, Krastl G, Filippi A. Dental injuries resulting from tracheal intubation--a retrospective study. Dent Traumatol. 2009;25:73-77. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |