Published online Jul 16, 2023. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v15.i7.510

Peer-review started: April 11, 2023

First decision: May 19, 2023

Revised: May 30, 2023

Accepted: June 9, 2023

Article in press: June 9, 2023

Published online: July 16, 2023

Processing time: 91 Days and 11.8 Hours

Candy cane syndrome (CCS) is a condition that occurs following gastrectomy or gastric bypass. CCS remains underrecognized, yet its prevalence is likely to rise due to the obesity epidemic and increased use of bariatric surgery. No previous literature review on this subject has been published.

To collate the current knowledge on CCS.

A literature search was conducted with PubMed and Google Scholar for studies from May 2007, until March 2023. The bibliographies of the retrieved articles were manually searched for additional relevant articles.

Twenty-one articles were identified (135 patients). Abdominal pain, nausea/vo

CCS remains underrecognized due to lack of knowledge about this condition. The growth of the obesity epidemic worldwide and the increase in bariatric surgery are likely to increase its prevalence. CCS can be prevented if an elongated blind loop is avoided or if a jejunal pouch is constructed after total gastrectomy. Diagnosis should be based on symptoms, endoscopy, and upper GI series. Blind loop resection is curative but complex and associated with significant complications. Endoscopic management using different approaches to divert flow is effective and should be further explored.

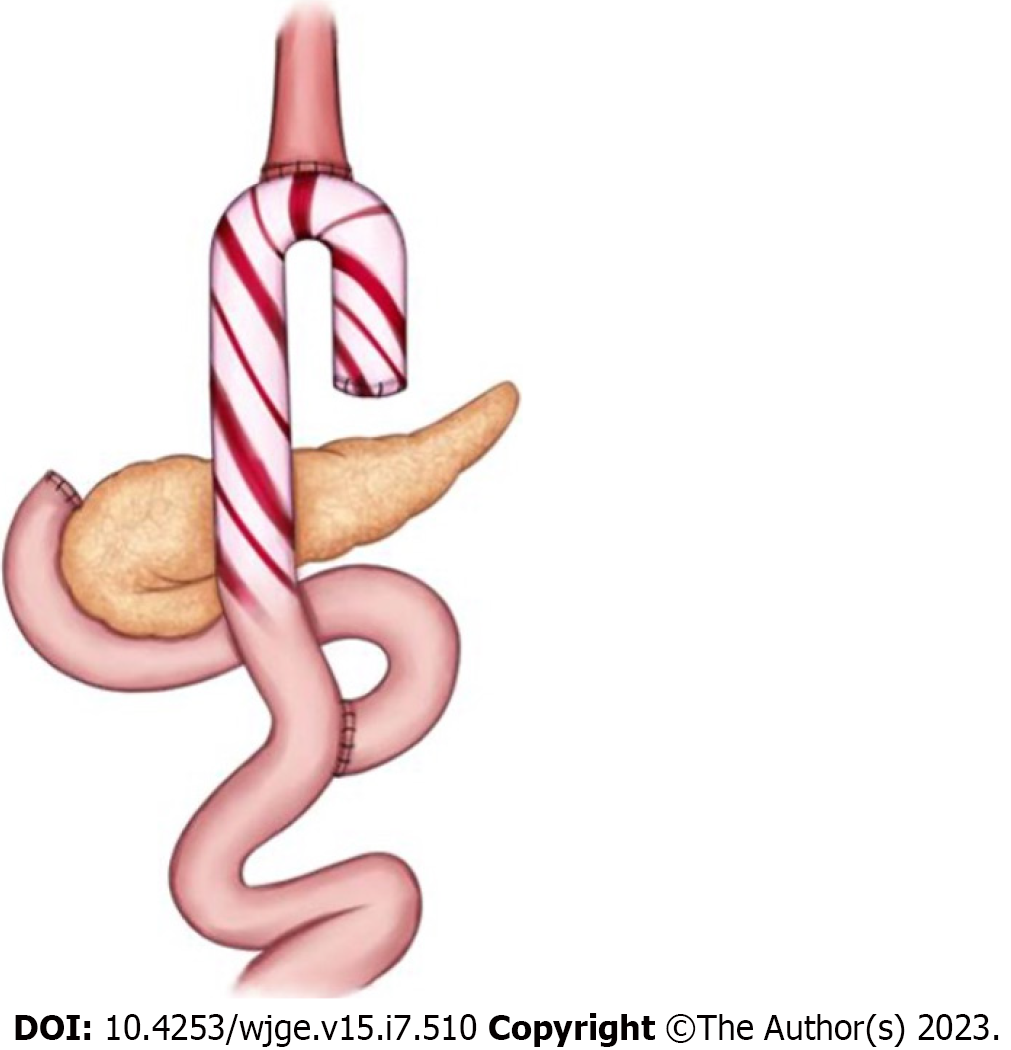

Core Tip: Enteral resections with side-to-side or end-to-end anastomosis, if a long blind end is left in place and dilates, can cause symptoms that may appear many years later. The classic designation for this clinical condition is blind pouch syndrome, although it is possible to find references under other designations, causing confusion. Candy cane syndrome (CCS) is a particular case of the blind pouch syndrome following gastrectomy or gastric bypass. CCS was first reported in a 2007 paper describing a series of patients with gastrointestinal symptoms associated with a long blind loop proximal to the gastro-jejunostomy after gastric bypass and creation of an end-to-side anastomosis to a jejunal loop. With unknown prevalence, few reports and case series have described the condition. Yet, with the increasing prevalence of obesity and number of operations being performed worldwide, surgical complications such as CCS are expected to become more frequent. Knowledge of candy cane syndrome is important to avoid delays in diagnosis and inadequate treatments. Thus, the goal of this study was to collate evidence on CCS symptoms, diagnosis, treatments, and outcomes. To the best of our knowledge, no previous literature review on this topic has been published.

- Citation: Rio-Tinto R, Canena J, Devière J. Candy cane syndrome: A systematic review. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2023; 15(7): 510-517

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v15/i7/510.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v15.i7.510

It has long been recognized that when long, blind enteral loops are left in place after a side-to-side or end-to-side anastomosis, they can dilate and be the cause of symptoms that may appear many years later[1]. The classic term for this clinical condition is “blind pouch syndrome”, although it is possible to find references under other designations, causing confusion[2,3]. A particular case of blind pouch syndrome following gastrectomy or gastric bypass is called candy cane syndrome (CCS). CCS was first reported in a 2007 paper describing a series of patients with gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms associated with a long blind loop proximal to the gastro-jejunostomy after gastric bypass and creation of an end-to-side anastomosis to a jejunal loop[4]. Few case reports and retrospective studies have described this condition. However, with the increasing prevalence of obesity and number of obesity-related surgeries being performed worldwide, CCS is expected to become more frequent[5].

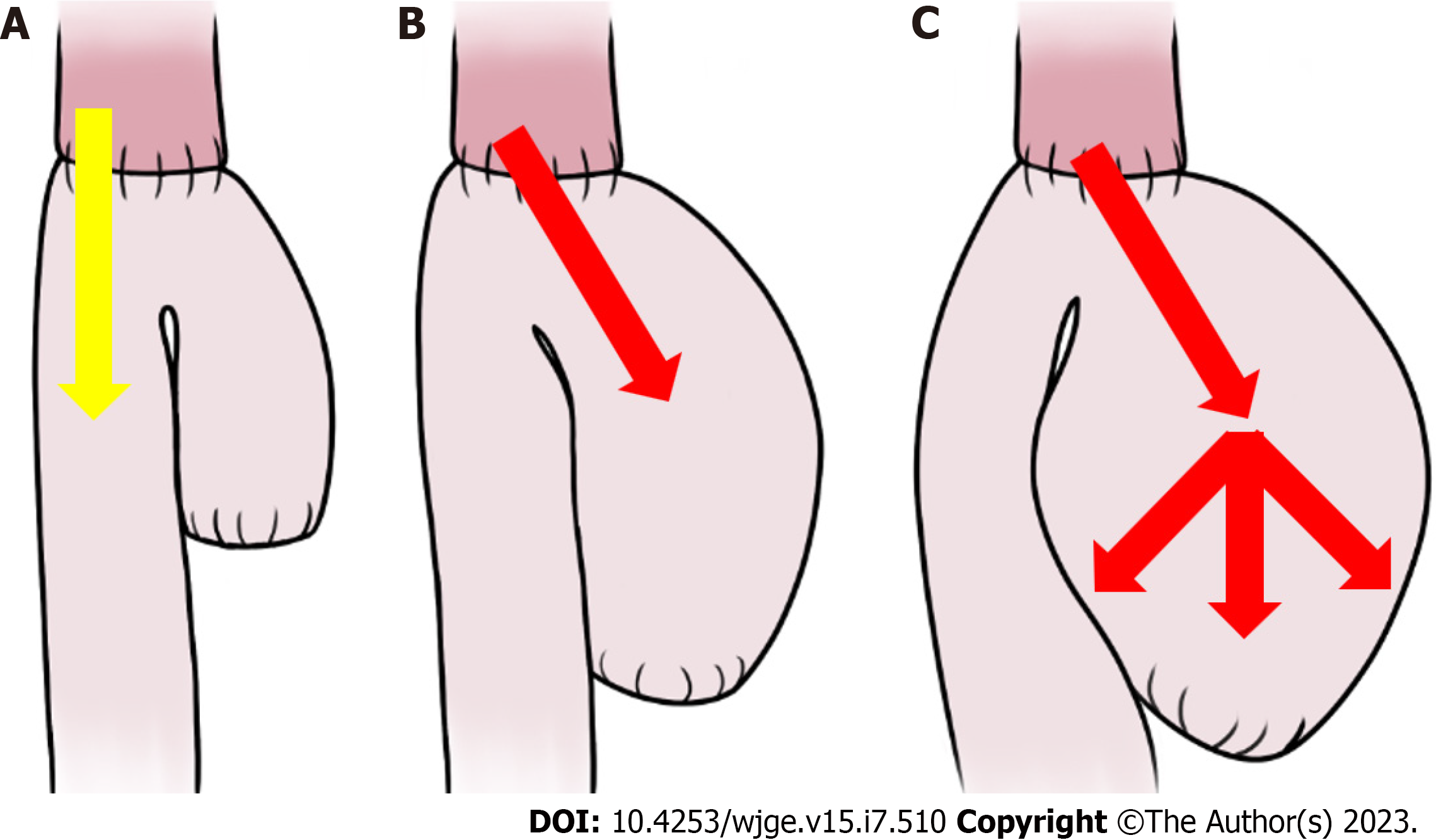

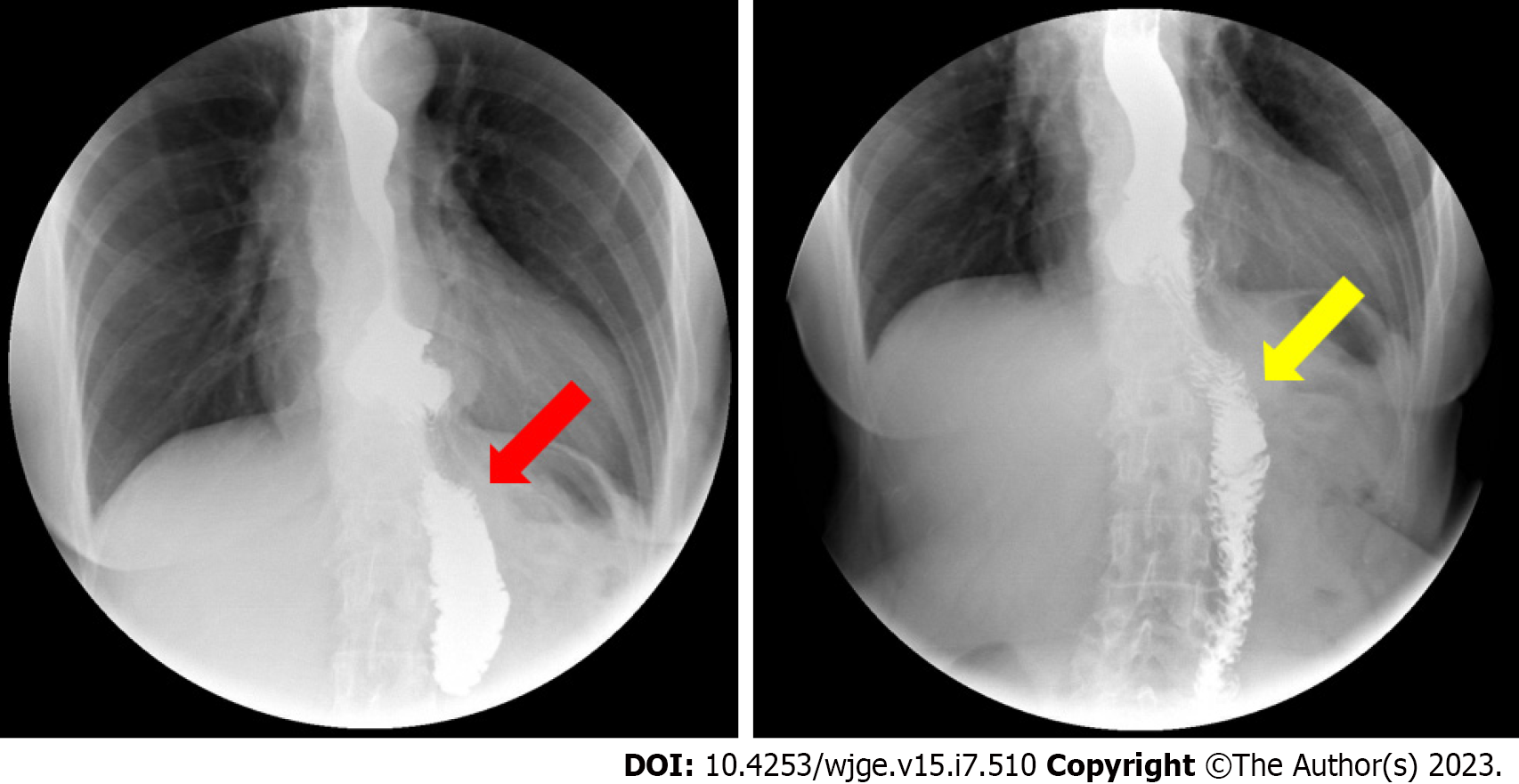

Probably, the pathophysiology of CCS is exclusively mechanical: A long, mispositioned blind loop preferentially directs luminal contents, increasing pressure and causing dilatation, pain, regurgitation, postprandial vomiting, and weight loss (Figure 1)[4-7]. Cachexia and spontaneous rupture of the blind loop are described[8,9]. Given its nonspecific presentation, the diagnosis of CCS is often subjective and based on clinical symptoms in conjunction with the endoscopic and/or radiographic appearance of a long and dilated blind jejunal limb proximal to the anastomosis, a finding which is known as the candy cane sign (Figure 2)[6,7,9,10].

CCS can be prevented by the avoidance of an unnecessary elongated jejunal (blind) loop proximal to the anastomosis during the initial surgery[2-4]. A blind loop of less than 3 to 4 cm is usually not associated with obstruction and therefore does not cause CCS. In addition, construction of a jejunal pouch after total gastrectomy prevents CCS and improves feeding, weight recovery, and quality of life[11-14].

For treatment, surgical resection of the dilated loop is curative but technically complex, due to previous surgeries and adhesions, and is associated with non-negligible morbidity[15,16]. Endoscopic management of CCS using various approaches to divert the flow from the blind loop is possible, safe, and effective[6,7,17-19].

Knowledge of CCS is important to avoid delays in diagnosis and inadequate treatments. Thus, the goal of this study was to collate evidence on CCS symptoms, diagnosis, treatments, and outcomes.

To the best of our knowledge, no previous literature review on this topic has been published.

A literature search was conducted using the PubMed database and Google Scholar, and by searching the electronic links to related articles, from May 1, 2007 through March 31, 2023.

Search terms included candy cane syndrome, blind pouch syndrome, blind loop syndrome, afferent loop syndrome, Roux limb syndrome, post-gastrectomy syndromes, complications of gastrectomy, side-to-side intestinal anastomosis, end-to-side intestinal anastomosis, and symptoms (pain, reflux, regurgitation, vomiting, and/or weight loss) after gastrectomy. The latter terms were used in various combinations for the search. Language restrictions were not applied.

The bibliographies of the retrieved articles were manually searched for additional relevant articles. The articles were carefully read to identify only those exclusively focusing on candy cane syndrome.

In accordance with the search criteria, we identified a total of 21 articles (135 patients), including 13 case reports, 3 case series, 4 retrospective studies, and 1 prospective study. Among these studies, the most reported symptoms were abdominal pain, nausea/vomiting, and reflux. In addition, almost all studies performed upper GI series and endoscopy for diagnosis.

Fourteen studies reported surgical resection of the excessive and/or dilated blind limb (13 studies, 111 patients) or construction of an enteral pouch (1 study, 1 patient) with resolution of symptoms in 73%–100% of patients[4,15,16,20-24]. In one case, the surgical procedure was performed through thoracoscopy[25]. These studies reported a total of 9 complications (1 biliary leak, 3 infections, 1 anastomosis ulcer, 1 enterotomy, 1 hematoma, 1 pneumonia\hepatic infarction, 1 leak) with no mortality[16,20,22].

Seven studies, including 5 case reports, 1 case series, and the only prospective study available, described various endoscopic approaches: In two studies, a lumen-apposing metal stent was used to divert the luminal content into the efferent loop[18,26]; in another two cases, a suture device was used to prevent the passage of food content into the blind loop[17-19]. These approaches are technically complex and have low reproducibility; A case report and a prospective study used a magnetic device to cut the tissue between the blind loop and the efferent loop, creating a pouch and allowing the free passage of the food contents[6,7]. In this case, the food is not retained in the blind loop and progresses unhindered to the efferent loop. All these endoscopic approaches led to resolution of symptoms in 100% of patients with no reported complications. One case report described CCS treatment by endoscopic dilation, which does not divert the blind loop, without success[9] (Table 1).

| Ref. | Type of study | n of patients | Symptoms | Timing of symptoms | Specific test | Management | Improvement rate | Complications |

| Dallal et al[4], 2007 | Case series | 3 | AP, N/V, GERD | 3 wk, 1 year, 3 years | UGS, endoscopy | Surgical resection | 1 | None |

| Romero-Mejía et al[28], 2010 | Case report | 1 | AP | 2 years | UGS, endoscopy | Surgical resection | 1 | None |

| Biju et al[29], 2012 | Case report | 1 | AP, N/V, GERD | 9 years | Endoscopy, UGS | Surgical resection | 1 | None |

| Razjouyan et al[9], 2015 | Case report | 1 | Dysphagia | 2 mo | UGS, endoscopy | Endoscopic dilation | 0 | None |

| Aryaie et al[20], 2017 | Retrospective | 19 | AP, N/V | 3-11 years | UGS, endoscopy | Surgical resection | 0.94 | 1 biliary leak |

| Marti Fernandez et al[30], 2017 | Case report | 1 | AP | Not mentioned | UGS, endoscopy | Surgical resection | 1 | None |

| Granata et al[17], 2019 | Case report | 1 | N/V, AP | 1 year | UGS, endoscopy | Endoscopic suture | 1 | None |

| Khan et al[15], 2018 | Case series | 3 | AP, N/V | 1 year | UGS, endoscopy, CT | Surgical resection | 1 | None |

| Kommunuri et al[21], 2018 | Case report | 1 | N/V, AP | 6 years | UGS, endoscopy | Surgical pouch | 1 | None |

| Frieder et al[23], 2019 | Retrospective | 26 | AP, N/V, GERD | 10 years | Not mentioned | Surgical resection | 0.92 | 1 leak |

| Cartillone et al[31], 2020 | Case report | 1 | AP, D, Vasomotor | 5 years | CT | Surgical resection | 1 | None |

| Kamocka et al[16], 2020 | Retrospective | 28 | AP, N/V, GERD | Not mentioned | CT, endoscopy, UGS | Surgical resection | 0.73 | 3 Infections, 1 anastomosis ulcer, 1 enterotomy, 1 hematoma |

| Cobb and Banki[25], 2020 | Case report | 1 | Dysphagia, regurgitation | 1 year | UGS, CT, endoscopy | Surgical resection1 | 1 | None |

| Wundsam et al[18], 2020 | Case series | 4 | Not mentioned | Not mentioned | Not mentioned | Endoscopic LAMS | 1 | None |

| Acín-Gándara and Ruiz-Úcar [22], 2021 | Case report | 1 | Dysphagia, GERD, AP | Not mentioned | Endoscopy, UGS | Surgical resection | 1 | Pneumonia, hepatic infarction |

| Greenberg et al[19], 2021 | Case report | 1 | AP, N/V, GERD | 8 years | Endoscopy, UGS | Endoscopic suture | 1 | None |

| Rio-Tinto et al[6], 2022 | Prospective | 14 | AP, N/V | Not mentioned | Endoscopy, UGS | Endoscopic marsupialization | 1 | None |

| Rio-Tinto et al[7], 2022 | Case report | 1 | AP, N/V | 24 mo | Endoscopy, UGS | Endoscopic marsupialization | 1 | None |

| Shamia et al[32], 2022 | Retrospective | 25 | AP, N/V, GERD | Not mentioned | Endoscopy | Surgical resection | 0.84 | Not mentioned |

| Ouazzani et al[26], 2023 | Case report | 1 | N/V, GERD | 40 years | Endoscopy, UGS | Endoscopic LAMS | 1 | None |

| Prakash et al[24], 2023 | Case report | 1 | GERD | 15 years | Endoscopy, UGS | Surgical resection | 1 | None |

CCS remains underrecognized and misdiagnosed due to a lack of knowledge about the condition. However, its manifestations have been described as common after gastrectomy[27]. In this review, we collected the current evidence on CCS symptoms, diagnosis, and treatment.

When the luminal contents preferentially pass into an overly long blind loop that retains food and distends, the characteristic symptoms of CCS appear, most commonly postprandial abdominal pain associated with nausea and vomiting. These symptoms can appear several years after surgery. Although CCS is a particular case of blind pouch syndrome, it has characteristics that justify being considered an independent clinical entity. As the obesity epidemic persists worldwide and the use of bariatric surgery increases, the prevalence of CCS will likely rise. Thus, CCS should be included in the group of post-gastrectomy syndromes and should be more readily recognized to avoid misdiagnosis, delayed treatment, and inappropriate interventions (Figure 3).

The differential diagnosis of CCS should include other surgical complications such as anastomotic stenosis, dysmotility syndromes secondary to surgery, and recurrence in cases of an oncologic indication for gastrectomy.

Collective evidence indicates that the diagnosis of CCS can be suggested based on clinical history and symptoms and should be confirmed by endoscopy and dynamic fluoroscopy.

The characteristic finding in upper GI series is a preferential filling of the blind loop followed by delayed passage of contrast into the efferent loop, the so-called "candy cane sign"[10].

Endoscopy in patients submitted to gastrectomy or gastric bypass should include the careful exploration of the blind loop and of the passage to the efferent loop. In these patients, access to the blind loop is usually easy and direct, and access to the efferent loop is difficult and done after passing through an angulation[21].

When CCS does arise, effective treatment options are available. Surgical resection of the excessively long and/or dilated loop is curative. However, this method is technically complex, due to previous surgeries and adhesions, and is associated with serious complications in a significant number of patients. By contrast, endoscopic management of CCS using various approaches to divert the flow from the blind loop is safe and effective and should be further explored.

CCS is still an unknown diagnosis for most physicians, including gastroenterologists who are often the first clinicians to deal with these patients.

Although it is underreported, the prevalence of CCS is probably higher than is commonly thought. Its diagnosis is based on clinical, endoscopic, and imaging findings. Symptoms such as dysphagia, pain, regurgitation, or reflux after food intake are relatively frequent in patients after gastrectomy or gastric bypass and should lead to a detailed clinical investigation. Although surgical revision of the blind loop is an effective treatment, it is associated with complications in frail patients with comorbidities. Sectioning of the septum and marsupialization is the current standard mini-invasive treatment for esophageal diverticula. The development of a simple and safe endoscopic technique, such as the blind loop marsupialization described in the only existing prospective study, will in our opinion be the preferred treatment for CCS in the future.

Candy cane syndrome (CCS) is a particular case of the blind pouch syndrome after gastrectomy or gastric bypass, so named in a 2007 paper describing a small series of patients with gastrointestinal symptoms associated with a long blind loop proximal to the gastro-jejunostomy after gastric bypass and creation of an end-to-side anastomosis to a jejunal loop. The pathophysiology of CCS appears to be predominantly mechanical, as an excessive long or mispositioned blind loop proximal to the anastomosis may preferably direct food and increase luminal pressure, causing dilatation, early satiety, fullness, pain, reflux, regurgitation, post-prandial vomiting, weight loss, and, ultimately, inability to eat and cachexia.

CCS remains underrecognized and misdiagnosed due to the lack of knowledge about this condition, however, its manifestations have been described as common after gastrectomy. Since gastroenterologists are often the first clinicians to come into contact with patients with CCS, it is important that this clinical condition be part of the list of differential diagnoses for patients with digestive symptoms after gastrectomy or gastric bypass. To our knowledge, there is no published review on this subject.

The objective of this work was to systematically gather all the published evidence on CCS, in order to make this clinical condition known and to systematize the diagnostic and therapeutic approach.

A literature search was conducted using PubMed and Google Scholar, and by searching in addition to electronic links to related articles, from May 1, 2007, through March 31, 2023. Search terms included candy cane syndrome, blind pouch syndrome, blind loop syndrome, afferent loop syndrome, Roux limb syndrome, post-gastrectomy syndromes, complications of gastrectomy, side-to-side intestinal anastomosis, end-to-side intestinal anastomosis, and symptoms (pain, reflux, regurgitation, vomiting, and/or weight loss) after gastrectomy. The bibliographies of the retrieved articles were manually searched for additional relevant articles.

We found 20 articles on CCS, most case reports or case series in which the treatment was surgical, usually resection of the blind loop. In seven articles the treatment was endoscopic, using lumen-apposing metal stents to divert the passage of the luminal contents (two case reports), suture devices to close the blind loop (two case reports), or by cutting the septum between the blind loop and the efferent loop, promoting the marsupialization of the blind loop (one clinical case and the only prospective study available). In one case, balloon dilatation was performed, without clinical success. In general, treatment results are good, but the surgical approach is associated with complications in a significant number of patients.

CCS remains an under-recognized clinical condition and since gastroenterologists are usually the first clinicians to come into contact with these patients it is important to make it more familiar. As the number of bariatric surgeries increases, it is likely that the number of patients with CCS will increase as well. CCS patients are usually frail, with comorbidities, and it is important to establish the best diagnostic and therapeutic approach. Surgical treatment is effective but is associated with complications and there is still no optimal and reproducible endoscopic treatment.

We believe that, in the same way that the treatment of Zenker's diverticulum has changed from surgery to the endoscopic section of the diverticular septum, in a simple, fast, effective and reproducible procedure, marsupialization of the septum between the blind loop and the efferent loop can become the ideal treatment for CCS.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: Portugal

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Ghannam WM, Egypt; Gupta R, India S-Editor: Li L L-Editor: A P-Editor: Xu ZH

| 1. | Botsford TW, Gazzaniga AB. Blind pouch syndrome. A complication of side to side intestinal anastomosis. Am J Surg. 1967;113:486-490. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Schlegel DM, Maglinte DD. The blind pouch syndrome. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1982;155:541-544. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Takiguchi S, Yano H, Sekimoto M, Taniguchi E, Monden T, Ohashi S, Monden M. Laparoscopic surgery for blind pouch syndrome following Roux-en Y gastrojejunostomy: report of a case. Surg Today. 1999;29:553-556. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Dallal RM, Cottam D. "Candy cane" Roux syndrome--a possible complication after gastric bypass surgery. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2007;3:408-410. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Jaruvongvanich V, Law R. Endoscopic management of candy cane syndrome: A sweet and attractive solution? Gastrointest Endosc. 2022;95:1254-1255. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Rio-Tinto R, Huberland F, Van Ouytsel P, Delattre C, Dugardeyn S, Cauche N, Delchambre A, Devière J, Blero D. Magnet and wire remodeling for the treatment of candy cane syndrome: first case series of a new approach (with video). Gastrointest Endosc. 2022;95:1247-1253. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Rio-Tinto R, de Campos ST, Marques S, Bispo M, Fidalgo P, Devière J. Endoscopic marsupialization for severe candy cane syndrome: long-term follow-up. Endosc Int Open. 2022;10:E1159-E1162. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Iaroseski J, Machado Grossi JV, Rossi LF. Acute abdomen and pneumoperitoneum: complications after gastric bypass in Candy Cane syndrome. Chirurgia (Bucur). 2022;34. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Razjouyan H, Tilara A, Chokhavatia S. Dysphagia After Total Gastrectomy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110:S262-263. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 10. | Coursier K, Verswijvel G. Candy cane sign. Abdom Radiol (NY). 2020;45:885-886. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Gertler R, Rosenberg R, Feith M, Schuster T, Friess H. Pouch vs. no pouch following total gastrectomy: meta-analysis and systematic review. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:2838-2851. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Dong HL, Huang YB, Ding XW, Song FJ, Chen KX, Hao XS. Pouch size influences clinical outcome of pouch construction after total gastrectomy: a meta-analysis. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:10166-10173. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Syn NL, Wee I, Shabbir A, Kim G, So JB. Pouch Versus No Pouch Following Total Gastrectomy: Meta-analysis of Randomized and Non-randomized Studies. Ann Surg. 2019;269:1041-1053. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Doussot A, Borraccino B, Rat P, Ortega-Deballon P, Facy O. Construction of a jejunal pouch after total gastrectomy. J Surg Tech Case Rep. 2014;6:37-38. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Khan K, Rodriguez R, Saeed S, Persaud A, Ahmed L. A Case series of candy cane limb syndrome after laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. J Surg Case Rep. 2018;2018:rjy244. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Kamocka A, McGlone ER, Pérez-Pevida B, Moorthy K, Hakky S, Tsironis C, Chahal H, Miras AD, Tan T, Purkayastha S, Ahmed AR. Candy cane revision after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Surg Endosc. 2020;34:2076-2081. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Granata A, Cicchese N, Amata M, De Monte L, Bertani A, Ligresti D, Traina M. "Candy cane" syndrome: a report of a mini-invasive endoscopic treatment using OverStitch, a novel endoluminal suturing system. Endoscopy. 2019;51:E16-E17. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Wundsam HV, Kertesz V, Bräuer F, Fischer I, Zacherl J, Függer R, Spaun GO. Lumen-apposing metal stent creating jejuno-jejunostomy for blind pouch syndrome in patients with esophago-jejunostomy after gastrectomy: a novel technique. Endoscopy. 2020;52:E35-E36. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Greenberg I, Braun D, Eke C, Lee D, Kedia P. Successful treatment of "candy cane" syndrome through endoscopic gastrojejunal anastomosis revision. Clin J Gastroenterol. 2021;14:1622-1625. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Aryaie AH, Fayezizadeh M, Wen Y, Alshehri M, Abbas M, Khaitan L. "Candy cane syndrome:" an underappreciated cause of abdominal pain and nausea after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2017;13:1501-1505. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Kommunuri J, Kulasegaran S, Stiven P. Blind Pouch Syndrome in Gastrojejunostomy. N Z Med J. 2018;131:74-77. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Acín-Gándara D, Ruiz-Úcar E, Medina-García M, Pereira-Pérez F. Revision of a Previous Capella Bypass due to dysphagia, GERD and Candy Cane Syndrome. Obes Surg. 2021;31:2348-2349. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 23. | Frieder JS, Betancourt A, Aleman R, Fonseca MC, Ortiz Gomez C, De Stefano F, Romero Funes D, Lo Menzo E, Szomstein S, Rosenthal RJ. Candycane Roux Limb Syndrome after Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass: Does Resection Improve the Symptoms of Nausea and Abdominal Pain? J Am Coll Surg. 2019;229:e1. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Prakash S, Saavedra R, Lehmann R, Mokadem M. Candy cane syndrome presenting with refractory heartburn 15 years after Roux-en-Y bypass. J Surg Case Rep. 2023;2023:rjad130. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Cobb T, Banki F. Thoracoscopic revision of a herniated Roux-en-Y esophagojejunostomy for treatment of "candy cane" syndrome. JTCVS Tech. 2020;2:153-155. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Ouazzani S, Gasmi M, Gonzalez JM, Barthet M. Candy cane syndrome: a new endoscopic treatment for this underappreciated surgical complication. Endoscopy. 2023;55:E414-E415. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Revisional Foregut Surgery. Borao FJ, Binenbaum SJ, Matharoo GS, Editors. Switzerland: Springer Nature Switzerland AG, 2020. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 28. | Romero-Mejía C, Camacho-Aguilera JF, Paipilla-Monroy O. ["Candy cane" Roux syndrome in laparoscopic gastric by-pass]. Cir Cir. 2010;78:347-351. [PubMed] |

| 29. | Biju A, Lane B, Chamberlain S. Candy Cane Roux Syndrome: A Not So Sweet Complication Following Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass. Am J Gastroenterol. 107:S297-298. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 30. | Marti Fernandez R, Marti Obiol R, Espi Macias A, Lopez Mozoz F. Candy Cane Syndrome after Gastric Cancer Surgery. J Clin Rev Case Rep. 2017;2. |

| 31. | Cartillone M, Kassir R, Mis TC, Falsetti E, D'Alessandro A, Chahine E, Chouillard E. König's Syndrome After Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass: Candy Cane Twist. Obes Surg. 2020;30:3251-3252. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Shamia A, Valdivieso S, Andrade J, Obregon F. Case series of long candy cane syndrome. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2022;18:S58. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |