Published online Nov 16, 2023. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v15.i11.676

Peer-review started: August 2, 2023

First decision: September 13, 2023

Revised: September 24, 2023

Accepted: October 9, 2023

Article in press: October 9, 2023

Published online: November 16, 2023

Processing time: 99 Days and 14.8 Hours

The incidence of ingestion of magnetic foreign bodies in the gastrointestinal tract has been increasing year by year. Due to their strong magnetic attraction, if multiple gastrointestinal foreign bodies enter the small intestine, it can lead to serious complications such as intestinal perforation, necrosis, torsion, and bleeding. Severe cases require surgical intervention.

We report a 6-year-old child who accidentally swallowed multiple magnetic balls. Under timely and safe anesthesia, the magnetic balls were quickly removed through gastroscopy before entering the small intestine.

General anesthesia with endotracheal intubation can ensure full anesthesia under the condition of fasting for less than 6 h. In order to prevent magnetic foreign bodies from entering the small intestine, timely and effective measures must be taken to remove the foreign bodies.

Core Tip: We report the successful and timely removal of multiple magnetic balls in a 6-year-old child using endoscopic retrieval under general anesthesia with endotracheal intubation. The procedure was efficient, safe, and free of complications. Prompt intervention and a multidisciplinary approach involving anesthesiologists and endoscopists are crucial in managing pediatric patients with ingestion of gastrointestinal foreign bodies. This report highlights the importance of timely intervention to prevent potential complications associated with magnetic foreign bodies.

- Citation: Tian QF, Zhao AX, Du N, Wang ZJ, Ma LL, Men FL. General anesthesia with endotracheal intubation ensures the quick removal of magnetic foreign bodies: A case report. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2023; 15(11): 676-680

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v15/i11/676.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v15.i11.676

Foreign body ingestion is a common problem that mainly occurs in children[1]. Over more than 80% of ingested foreign objects may pass through the gastrointestinal tract uneventfully, while the rest require treatment2. Among them, magnetic foreign bodies pose a unique challenge due to their potential for complications. These objects, often small and attractive to children, can be accidentally ingested or inserted into the gastrointestinal tract. The ingestion of these magnetic balls can lead to intestinal perforation due to their ability to attract and cause pressure necrosis on tissues[2,3].

Endotracheal intubation under general anesthesia and timely endoscopic intervention can effectively prevent the passage of magnetic foreign bodies into the small intestine. This report describes the successful removal of multiple magnetic balls in a 6-year-old child.

A 6-year-old girl attended the clinic one hour after accidentally swallowing magnetic balls.

The girl presented to the hospital after accidentally swallowing multiple magnetic balls.

The child had been in good health.

The child denied any family history.

The patient's vital signs were stable. Physical examination revealed a soft abdomen with no tenderness or rebound tenderness. Bowel sounds were normal.

Routine blood tests showed no abnormalities.

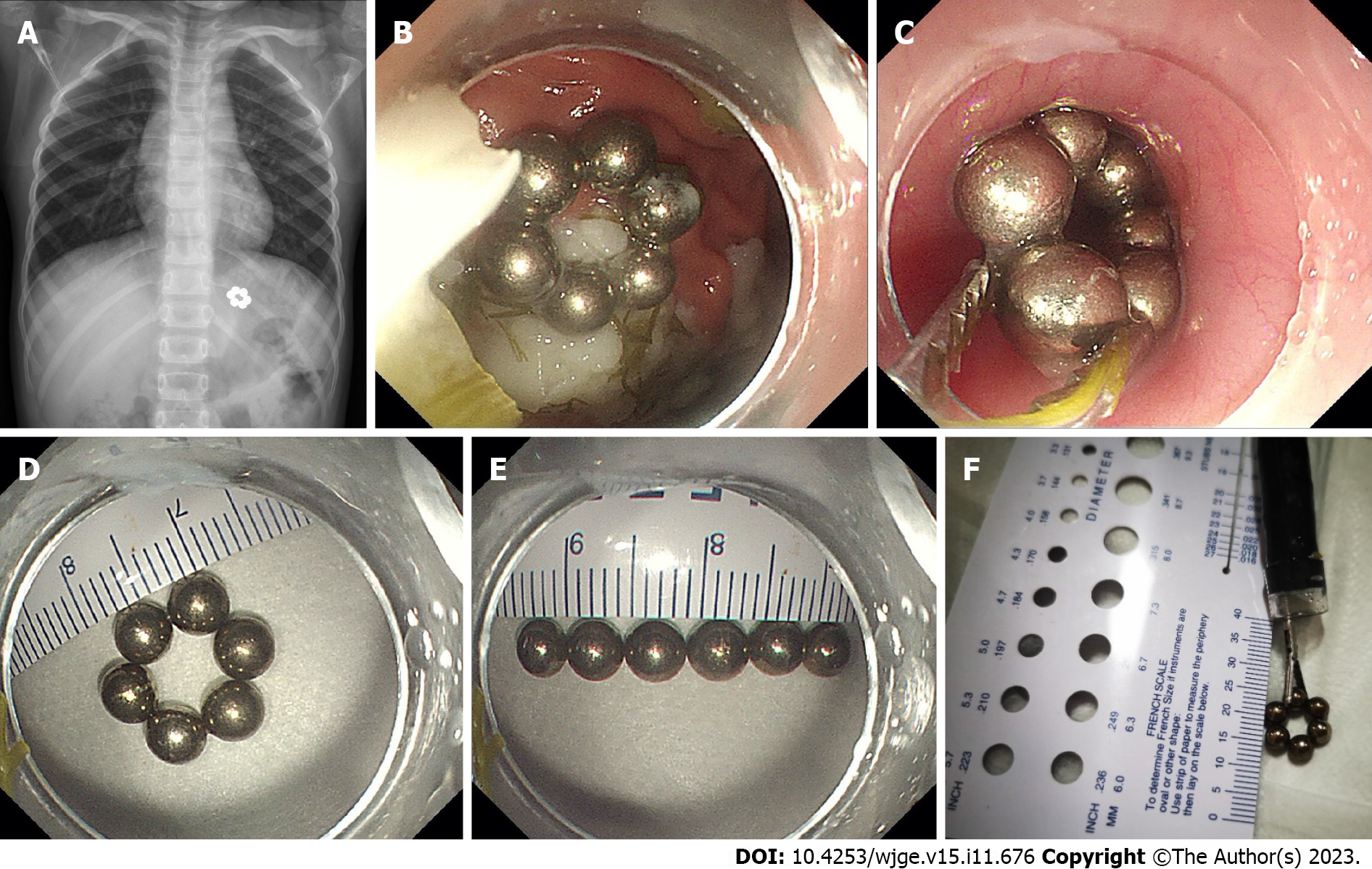

The abdominal X-ray revealed that the balls had attracted together and formed a ring-like structure in the upper left abdomen (Figure 1A).

Multiple magnetic foreign bodies in the gastrointestinal tract.

The child had consumed solid food approximately 2 h before coming to the hospital. In order to avoid the balls entering into the small intestine, our anesthesiologist promptly evaluated the child and performed the necessary airway management. Then the child was provided general anesthesia with endotracheal intubation. The endoscopy was successfully performed only 38 min after admission. During the endoscopic examination, the magnetic balls were visualized inside the stomach, and arranged in a ring formation (Figure 1B). No mucosal damage was observed, but significant solid food residue was present (Figure 1B). Using grasping forceps, one of the magnetic balls was securely clamped, and with the help of their mutual attraction, all six balls with a diameter of approximately 2.5 cm were successfully removed (Figure 1C-F).

No mucosal or abrasion injuries were observed during the retrieval. After the procedure, the child's endotracheal tube was successfully removed, and she was transferred to the recovery room for observation. The patient reported no discomfort or complications postoperatively. The follow-up visit demonstrated a normal healthy child with no sequelae or complications.

Ingestion of foreign bodies is a common pediatric emergency, especially among young children1. Small objects can usually pass through the gastrointestinal tract naturally, but larger or sharp objects may become lodged or cause mucosal injury[2]. Magnetic objects pose a unique risk, as they can lead to pressure necrosis and perforation if not promptly removed.

The attractive force between the magnetic objects can cause them to adhere to each other across the intestinal wall, leading to pressure necrosis, perforation, or obstruction. The clinical presentation of patients with ingestion of magnetic foreign bodies can vary widely, ranging from asymptomatic to severe abdominal pain, vomiting, and gastrointestinal bleeding[4].

Diagnosis of magnetic foreign bodies is primarily based on a combination of clinical history, physical examination, and radiographic imaging. Abdominal X-rays, including both anteroposterior and lateral views, are commonly used to identify the presence, location, and number of magnetic objects within the gastrointestinal tract. In some cases, additional imaging modalities such as computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging may be required for a more detailed evaluation[5].

Management of magnetic foreign bodies depends on several factors, including the location, number, size, and clinical symptoms of the patient. In asymptomatic patients with small, single magnetic object, conservative management with close observation and serial radiographic monitoring may be appropriate. However, in symptomatic patients or those with ingestion of multiple or large magnetic foreign bodies, endoscopic or surgical intervention may be necessary to remove the objects and prevent potential complications[6,7].

Children have a shorter gastric emptying time than adults, with a reported gastric emptying time after consuming solid food being less than 4 h for children[8]. For children, this means that foreign objects accidentally swallowed by the child may be expelled into the small intestine within a short period of time. Therefore, timely endoscopic intervention can prevent magnetic foreign bodies from entering the small intestine, thereby avoiding the occurrence of intestinal perforation, bleeding, ischemia, and necrosis. Current guidelines recommend that children undergo general anesthesia after fasting for more than 6 h[9]. However, after 6 h, as food is emptied from the stomach, foreign objects may also be expelled into the small intestine, thereby increasing the difficulty of their removal. General anesthesia with endotracheal intubation can prevent the occurrence of aspiration and choking after anesthesia, ensuring the safe implementation of endoscopic procedures under general anesthesia.

In this case, timely performing endoscopic removal under the protection of endotracheal intubation helped prevent the migration of the magnetic balls into the small intestine, reducing the difficulty of retrieval and the risk of bowel perforation.

Magnetic objects can pose a unique risk, as they can lead to pressure necrosis and perforation if not promptly removed. In this case, the timely and safe performance of endoscopic removal under the protection of endotracheal intubation helped prevent the migration of the magnetic balls into the small intestine, reducing the difficulty of retrieval and the risk of bowel perforation.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Zharikov YO, Russia S-Editor: Liu JH L-Editor: A P-Editor: Liu JH

| 1. | Demiroren K. Management of Gastrointestinal Foreign Bodies with Brief Review of the Guidelines. Pediatr Gastroenterol Hepatol Nutr. 2023;26:1-14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Zhang S, Zhang L, Chen Q, Zhang Y, Cai D, Luo W, Chen K, Pan T, Gao Z. Management of magnetic foreign body ingestion in children. Medicine (Baltimore). 2021;100:e24055. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Cai DT, Shu Q, Zhang SH, Liu J, Gao ZG. Surgical treatment of multiple magnet ingestion in children: A single-center study. World J Clin Cases. 2020;8:5988-5998. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Zhang RY, Cai P, Zhang TT, Zhu J, Chen JL, Zhao HW, Jiang YL, Wang Q, Zhu ML, Zhou XG, Xiang XL, Hu FL, Gu ZC, Zhu ZW. Clinical predictors of surgical intervention for gastrointestinal magnetic foreign bodies in children. BMC Pediatr. 2023;23:323. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Ayalon A, Fanadka F, Levov D, Saabni R, Moisseiev E. Detection of Intraorbital Foreign Bodies Using Magnetic Resonance Imaging and Computed Tomography. Curr Eye Res. 2021;46:1917-1922. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Jin Y, Gao Z, Zhang Y, Cai D, Hu D, Zhang S, Mao J. Management of multiple magnetic foreign body ingestion in pediatric patients. BMC Pediatr. 2022;22:448. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Huang K, Zhao X, Chen X, Gao Y, Yu J, Wu L. Analysis of Digestive Endoscopic Results During COVID-19. J Transl Int Med. 2021;9:38-42. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Beck CE, Witt L, Albrecht L, Dennhardt N, Böthig D, Sümpelmann R. Ultrasound assessment of gastric emptying time after a standardised light breakfast in healthy children: A prospective observational study. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2018;35:937-941. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Smith I, Kranke P, Murat I, Smith A, O'Sullivan G, Søreide E, Spies C, in't Veld B; European Society of Anaesthesiology. Perioperative fasting in adults and children: guidelines from the European Society of Anaesthesiology. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2011;28:556-569. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 556] [Cited by in RCA: 542] [Article Influence: 38.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |