Published online Sep 16, 2022. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v14.i9.575

Peer-review started: May 5, 2022

First decision: June 16, 2022

Revised: July 11, 2022

Accepted: August 6, 2022

Article in press: August 6, 2022

Published online: September 16, 2022

Processing time: 134 Days and 6.5 Hours

Tuberculosis is endemic in Senegal. While its extra-pulmonary localization is rare, esophageal tuberculosis, particularly the isolated form, is exceptional. We report here a case of isolated esophageal tuberculosis in an immunocompetent patient.

A 58-year-old man underwent consultation for mechanical dysphagia that had developed over 3 mo with non-quantified weight loss, anorexia, and fever. Upper digestive endoscopy showed extensive ulcerated lesions, suggesting neoplasia. The diagnosis was confirmed by histopathology, which showed gigantocellular epithelioid granuloma surrounding a caseous necrosis. Thoracoabdominal computed tomography scan did not show another localization of the tuberculosis. The outcome was favorable with treatment.

Esophageal tuberculosis should be considered when dysphagia is associated with atypical ulcerated lesions of the esophageal mucosa, in an endemic area.

Core Tip: Isolated esophageal tuberculosis is rare. Often discovered during the exploration of dysphagia, the endoscopic aspects are not specific, and can simulate several pathologies. Biopsies can help with diagnosis by showing the granuloma to histology or by allowing molecular biology examinations. In this manuscript, we report a case of isolated esophageal tuberculosis with vast ulcers of the esophagus, which evolved without sequelae after treatment.

- Citation: Diallo I, Touré O, Sarr ES, Sow A, Ndiaye B, Diawara PS, Dial CM, Mbengue A, Fall F. Isolated esophageal tuberculosis: A case report. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2022; 14(9): 575-580

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v14/i9/575.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v14.i9.575

Tuberculosis is endemic in Senegal, where it constitutes a major public health problem. In 2020, 12808 new cases of tuberculosis were reported in Senegal, the majority of which were pulmonary (National Controlling Tuberculosis Program, data not published). Extrapulmonary forms of tuberculosis are frequent, whether or not they are associated with pulmonary involvement. In the digestive tract, the terminal ileum and the cecum are most often affected. Esophageal localization is rare, especially in its isolated form. We report herein a case of isolated esophageal tuberculosis in an immunocompetent patient who responded well to antibacillary treatment.

A 58-year-old patient was seen in our department for dysphagia that had developed over 3 mo.

The patient had dysphagia that had been evolving for 3 mo with non-quantified weight loss, nonselective anorexia, and nocturnal fever.

The patient had undergone appendectomy at 23-years-old.

The patient’s other personal and family histories were unremarkable.

The patient was in good general condition (World Health Organization performance status of 0), with a body mass index of 21.55 kg/m². Clinical examination was normal.

Biological investigations (blood count, liver function tests, glycemia, renal function, and C-reactive protein) were normal. The viral serologies for hepatitis B, hepatitis C, and human immunodeficiency virus were negative.

The thoracoabdominal computed tomography (CT) scan did not show any mediastinal lymph nodes in contact with the esophagus or other foci of tuberculosis.

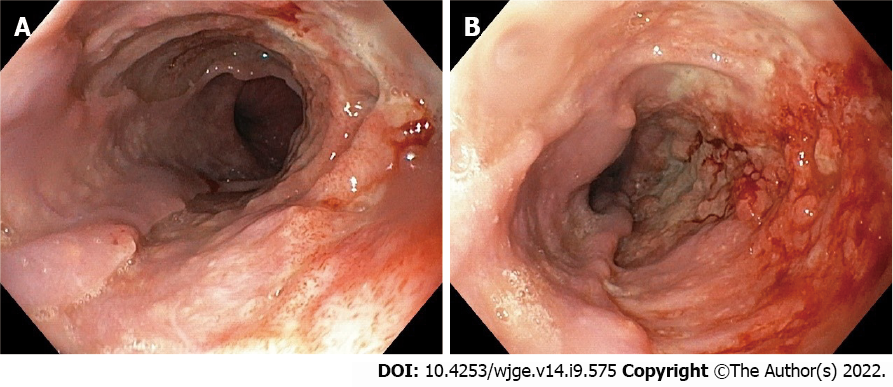

Upper gastrointestinal (GI) endoscopy showed a jagged appearance of the thoracic esophageal mucosa for about 12 cm, stopping 3 cm above the cardia, with large irregular ulcers and raised contours. Nodules were present both at the level of the ulcers and in the normal-appearing mucosa (Figure 1A). Chromoendoscopy with narrow-band imaging did not detect areas that might suggest dysplasia or carcinoma (Figure 1B).

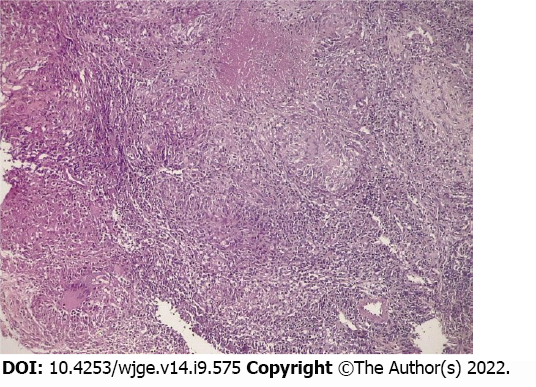

Esophageal biopsies revealed a deep loss of wall tissue, reaching the muscularis mucosa. The normal tissue was replaced by granulation tissue containing a tuberculoid granuloma with several follicles consisting of epithelioid and multinucleated Langerhans histiocytes, surrounding a caseous necrosis (Figure 2). Neither culture of tissue samples nor PCR test for Mycobacterium tuberculosis were performed. Sputum and gastric acid liquid after aspiration were negative for acid-fast bacilli (AFB).

Isolated esophageal tuberculosis.

An antituberculosis treatment was initiated [rifampicin, isoniazid, ethambutol, and pyrazinamide (RHEZ) and administered for 2 mo, and with rifampicin and isoniazid (RH) for 4 mo]. The patient showed good tolerance.

The patient’s outcome was favorable, with a clear improvement of dysphagia after 15 d of treatment, which disappeared after 5 wk. Upper digestive endoscopy after 4 mo of treatment showed a normal esophageal mucosa. Six months after stopping the treatment, the patient was well, had regained weight, and did not complain of dysphagia.

Described for the first time in 1837 by Denonvilliers during an autopsy, infectious esophagitis due to tuberculosis is rare, even in countries with high tuberculosis endemicity. The esophageal localization represents 0.2%-1% of tuberculosis cases of the GI tract[1,2]. This low incidence can be explained by several mechanisms that allow the esophagus to fight infection, in particular, peristaltic movements leading to emptying of the contents into the stomach, and the presence of mucus and saliva lining the mucosa and its squamous epithelium[1]. These mechanisms provide a barrier against primary contamination caused by the ingestion of food or saliva containing germs such as M. tuberculosis. However, secondary contamination by contact with neighboring organs, especially in cases of tuberculosis in paraesophageal lymph nodes, is possible[3]. Blood-borne contamination is rare.

The most common symptom during esophageal tuberculosis is dysphagia (90% of cases), which was the main sign in our patient. Odynophagia, pyrosis, and chest pain may also be present[4]. The occurrence of coughing at mealtime should raise suspicion of an esotracheal or esophageal-mediastinal fistula, which is present in 13%-50% of cases[5]. The presence of hematemesis can also provide further evidence of a fistula[6].

The endoscopic appearance of esophageal tuberculosis is variable and nonspecific. In our patient, the lesion was located in the lower two-thirds of the esophagus and consisted of a large ulcer with raised contours, associated with micronodules. The esophagus can be affected throughout its length, although the lesion is most often located in the middle third[3,7,8], because of the extensive lymphoid tissue in this region. Endoscopy may show an ulcer of variable size, superficial with regular contours or irregular and infiltrative simulating neoplasia, or show a more or less ulcerated budding aspect of the mucosa[3,9]. An extrinsic compression aspect with a mucosa of normal appearance can also be found[8]. Endo

Histology can help in the diagnosis of esophageal tuberculosis. Mucosal biopsies during upper GI endoscopy can show the presence of a tuberculous granuloma or AFB in about 50% of cases[10,11], but sometimes neither of these lesions is found[12]. In our patient, an epithelioid gigantocellular granuloma with caseous necrosis was present on histology (Figure 3), confirming the diagnosis of esophageal tuberculosis. To improve diagnostic success, deep biopsy samples should be taken from ulcerated areas, as granulomas are most often found in the submucosa[1,8,11]. If endoscopic biopsies are not contributive, deep esophageal biopsy or fine-needle aspiration of a satellite lymph node, guided by endoscopic ultrasound, make it possible to find an epithelioid granuloma on histology (reportedly in 94.7% to 100% of cases, with caseous necrosis and/or AFB present in 55% to 75% of those cases)[7,11]. Histological samples are also used for PCR or culturing methods to identify M. tuberculosis. If an epithelioid granuloma without caseous necrosis is present, a differential diagnosis with sarcoidosis, Crohn’s disease, or a carcinoma must be considered.

The treatment of esophageal tuberculosis is essentially medical, according to the standard protocol (rifampicin, isoniazid, ethambutol, and pyrazinamide daily for 2 mo, followed by rifampicin and isoniazid daily for 4 mo) for at least 6 mo. However, the optimal duration is not clinically established. In the case of fistula, clips are the reference treatment for lesion closure[11,13]. The outcome during treatment for esophageal tuberculosis is favorable and without sequelae in almost all cases[3,7,8,11]. In our patient, no sequelae were noted during the follow-up. Upper digestive endoscopy, 4 mo after the beginning of treatment, was normal. The patient had no complaints at 6 mo after the end of treatment.

Esophageal tuberculosis is a rare cause of infectious esophagitis, even in a country where tuberculosis is endemic. Nevertheless, esophageal tuberculosis should be considered when dysphagia is associated with atypical ulcerated lesions of the esophageal mucosa. The presence of gigantocellular epithelioid granulomas on esophageal biopsies confirms the diagnosis. The patient’s outcome is generally favorable after antibacillary treatment, as illustrated by our observation.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: Senegal

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): E

P-Reviewer: Anandan H, India; Meng FZ, China; Novita BD, Indonesia S-Editor: Wu YXJ L-Editor: A P-Editor: Wu YXJ

| 1. | Diallo I, Omar Soko T, Rajack Ndiaye A, Klotz F. Tuberculose abdominale. EMC - Gastro-entérologie. 2019;37:1-13. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 2. | Debi U, Ravisankar V, Prasad KK, Sinha SK, Sharma AK. Abdominal tuberculosis of the gastrointestinal tract: revisited. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:14831-14840. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 231] [Cited by in RCA: 216] [Article Influence: 19.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 3. | Zhu R, Bai Y, Zhou Y, Fang X, Zhao K, Tuo B, Wu H. EUS in the diagnosis of pathologically undiagnosed esophageal tuberculosis. BMC Gastroenterol. 2020;20:291. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Vahid B, Huda N, Esmaili A. An unusual case of dysphagia and chest pain in a non-HIV patient: esophageal tuberculosis. Am J Med. 2007;120:e1-e2. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Nagi B, Lal A, Kochhar R, Bhasin DK, Gulati M, Suri S, Singh K. Imaging of esophageal tuberculosis: a review of 23 cases. Acta Radiol. 2003;44:329-333. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Jain SS, Somani PO, Mahey RC, Shah DK, Contractor QQ, Rathi PM. Esophageal tuberculosis presenting with hematemesis. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2013;5:581-583. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Tang Y, Shi W, Sun X, Xi W. Endoscopic ultrasound in diagnosis of esophageal tuberculosis: 10-year experience at a tertiary care center. Dis Esophagus. 2017;30:1-6. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Xiong J, Guo W, Guo Y, Gong L, Liu S. Clinical and endoscopic features of esophageal tuberculosis: a 20-year retrospective study. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2020;55:1200-1204. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Seo JH, Kim GH, Jhi JH, Park YJ, Jang YS, Lee BE, Song GA. Endosonographic features of esophageal tuberculosis presenting as a subepithelial lesion. J Dig Dis. 2017;18:185-188. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Park JH, Kim SU, Sohn JW, Chung IK, Jung MK, Jeon SW, Kim SK. Endoscopic findings and clinical features of esophageal tuberculosis. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2010;45:1269-1272. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Dahale AS, Kumar A, Srivastava S, Varakanahalli S, Sachdeva S, Puri AS. Esophageal tuberculosis: Uncommon of common. JGH Open. 2018;2:34-38. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Rana SS, Bhasin DK, Rao C, Srinivasan R, Singh K. Tuberculosis presenting as Dysphagia: clinical, endoscopic, radiological and endosonographic features. Endosc Ultrasound. 2013;2:92-95. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Rana SS, Mandavdhare H, Sharma V, Sharma R, Dhalaria L, Bhatia A, Gupta R, Dutta U. Successful closure of chronic, nonhealing tubercular esophagobronchial fistula with an over-the-scope clip. J Dig Endosc 2017; 8 (1) : 33-5.. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |