Published online Aug 16, 2022. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v14.i8.502

Peer-review started: January 18, 2022

First decision: April 17, 2022

Revised: April 29, 2022

Accepted: July 16, 2022

Article in press: July 16, 2022

Published online: August 16, 2022

Processing time: 208 Days and 18.4 Hours

Almost half of the patients with colorectal cancer (CRC) will experience local-regional recurrence after standard surgical excision. Many local recurrences of colorectal cancer (LRCC) do not grow intraluminally, and some may be covered by a normal mucosa so that they could be missed by colonoscopy. Early detection is crucial as it offers a chance to achieve curative reoperation. Endoscopic ultra

We report a series of five cases referred to surveillance for LRCC with negative colonoscopy and/or negative endoscopic biopsies. EUS-FNA confirmed LRCC implanted deep into the third and fourth wall layer with normal first and second layer.

Assessment for LCRR is still problematic and may be very tricky. EUS and EUS-FNA may be useful tools to exclude local recurrence.

Core Tip: The local recurrence of colorectal adenocarcinoma that has been implanted deeply in the submucosal layers is usually missed by colonoscopy, despite that some cases show submucosal elevation. Endoscopic biopsies often give negative results, so endoscopic ultrasound fine-needle aspiration can be used to confirm the diagnosis and give patients a better chance for proper management.

- Citation: Okasha HH, Wahba M, Fontagnier E, Abdellatef A, Haggag H, AbouElenin S. Hidden local recurrence of colorectal adenocarcinoma diagnosed by endoscopic ultrasound: A case series. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2022; 14(8): 502-507

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v14/i8/502.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v14.i8.502

In patients with curatively resected colorectal cancer (CRC), local recurrence is often considered a clinical dilemma difficult to treat, may cause markedly disabling symptoms, and usually has a bad prognosis[1,2]. Several factors were incriminated in the recurrence as positive surgical margins, especially with inadequate excision, inadequate nodal dissection, implantation of exfoliated malignant cells into the deep layers, and changed biological characters at the site of large bowel anastomosis[3]. However, while colonoscopy remains the gold standard method of detecting local recurrences of colorectal cancer (LRCC) and metachronous lesions, it is considered an imperfect tool even in the best hands, with missing rates of adenocarcinoma ranging from 1% to 3%[4,5]. Unfortunately, not all local recurrences are detectable at the mucosal surface with false-negative colonoscopy. In these cases, endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) plays an irreplaceable role allowing highly detailed visualization of all the bowel wall layers with all the surrounding structures[6].

The great value of EUS in the evaluation for possible CRC recurrence nowadays comes from its ability to direct fine-needle aspiration (FNA) and fine needle biopsy, thus allowing the acquisition of tissue samples for histological and immunohistochemical examination, and providing a definitive diagnosis.

There are two studies on EUS FNA that showed its high accuracy in the diagnosis of subepithelial and extra-luminal lesions of the colon and rectum[7,8]. In both studies, the accuracy of EUS-FNA was 90%-95% compared with an 82% accuracy for imaging alone[8].

All patients gave their informed written consent before the procedure. All patients had MRI examination before EUS examination.

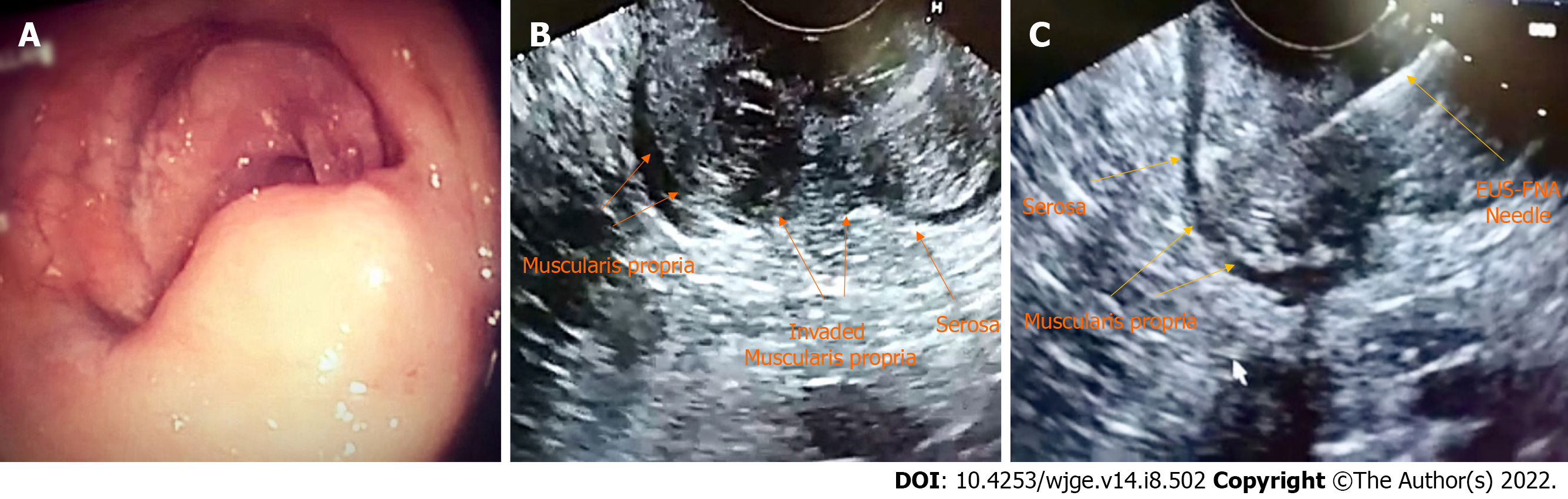

All examinations were done under deep sedation with IV propofol. All cases had ano-rectal lesions, maximum 15-20 cm from the anal verge, which are easy to be scanned by the side view scope. No right hemicolon masse were included as they are very difficult to be approached by the side view scope. For EUS-FNA, we used Cook 22G needles (Echotip, Wilson-Cook) (Figure 1).

Case 1: This was a 70-year-old male patient. During LRCC surveillance, no lesions were detected by colonoscopy. The patient experienced unexplained weight loss and was referred for EUS assessment.

Case 2: This was a 45-year-old male patient. LRCC surveillance colonoscopy revealed a submucosal lesion at the rectal anastomotic line, and multiple endoscopic biopsies got negative results repeatedly. The patient was referred for EUS examination.

Case 3: This was a 45-year-old female patient who presented with difficult defecation. Colonoscopy revealed narrowed rectal anastomotic line, but biopsies were negative.

Case 4: This was a 48-year-old male patient. During LRCC surveillance, submucosal elevation at the sigmoido-colonic anastomotic line was noticed by colonoscopy, and endoscopic biopsies showed negative results.

Case 5: This was a 46-year-old male patient. During LRCC surveillance, colonoscopy showed a sub

Case 1: The patient experienced unexplained weight loss and was referred for EUS assessment.

Cases 2, 4, and 5: The patients underwent LRCC surveillance.

Case 3: The patient presented with difficult defecation.

Cases 1-5: The patients had a history of CRC surgical excision.

Cases 1-5: No notable personal or family medical history.

Case 1: Unremarkable apart from unexplained weight loss.

Cases 2-5: Unremarkable physical examination.

Case 1: No other abnormalities were noted apart from mild microcytic hypochromic anemia.

Cases 2-5: No other abnormalities noted.

Case 1: EUS assessment revealed a 2.8 cm × 4 cm homogenous mass at the rectal anastomotic line, arising from the fourth wall layer. FNA was performed, and pathological examination confirmed adenocarcinoma.

Case 2: EUS examination showed a 1.9 cm × 2.9 cm homogenous mass, arising from the fourth layer. FNA was performed, and pathological assessment confirmed adenocarcinoma recurrence.

Case 3: EUS was conducted and revealed a homogeneous mass measuring 3 cm × 3.3 cm, arising from the fourth layer. FNA was carried out, and adenocarcinoma local recurrence into the deep submucosal layers confirmed.

Case 4: EUS revealed a heterogeneous mass measuring 2.3 cm × 4.2 cm arising from the third layer. FNA was performed, and pathological studies confirmed adenocarcinoma recurrence.

Case 5: EUS was carried out and revealed a 1.2 cm × 2.4 cm homogeneous mass, arising from the fourth layer at the ano-rectal anastomotic line. FNA was performed, and the result confirmed adenocarcinoma.

We report five case series referred to surveillance for LRCC with negative colonoscopy and/or negative endoscopic biopsies. EUS-FNA confirmed LRCC implanted deep into the third and fourth wall layer with normal first and second layer.

Case 1: The patient underwent Lt hemi-colectomy for local recurrence and was referred to medical oncology.

Case 2: Partial colectomy was carried out.

Case 3: The patient received chemotherapy for cancer colon.

Case 4: The patient was referred to medical oncology.

Case 5: The patient received chemo-radiotherapy for ano-rectal cancer.

In all cases, the patients were referred to medical cancer institute.

CRC is one of the common and lethal malignancies worldwide and is considered the second leading cause of cancer deaths in the United States[9]. Most of CRC patients underwent surgical excision aiming at curative treatment, and up to 40% of patients with the locoregional disease will develop recurrent cancer, of which 90% will occur within 5 years[10,11].

The postoperative surveillance of patients treated for CRC is a clinical challenge, first due to distorted anatomy and scarring and second because of intent to prolong survival by diagnosing recurrent and metachronous cancers at a curable stage. LRCC surveillance strategies combined different modalities, including clinical assessment, tumor marker carcinoembryonic antigen, computed tomography (CT) scans, and endoluminal imaging, including colonoscopy, sigmoidoscopy, EUS, and CT colonography. The optimal surveillance strategy is still not clearly defined.

A number of studies have shown EUS to be very accurate in detecting LCRR, with EUS-FNA being able to provide tissue confirmation[12,13].

Several guidelines and organizations recommend EUS in post-treatment surveillance for resected colon and rectal cancer. The NCCN guidelines state that flexible sigmoidoscopy with EUS or MRI should be done every 3 to 6 mo for 2 years, then every 6 mo to complete 5 years for patients with rectal cancer undergoing transanal excision only[14]. The United States Multi-Society Task Force include EUS as an alternative to sigmoidoscopy in the testing strategy for patients at higher risk of recurrence[15].

In patients with a curative resection for rectal cancer, the current US Multi-Society Task Force recommendation suggests EUS at 3-6 mo for the first 2 years after resection as a reasonable option[16]. It is noteworthy that not all recurrences are evident at the mucosal surface, so in those cases the benefit of EUS will be restricted in highly detailed visualization and assessment of all the bowel wall layers with all the surrounding structures[6].

Our study showed a rare clinical scenario of hidden implanted adenocarcinoma in the third and fourth layer with an intact mucosal layer, so it was not evident intraluminally and missed by colonoscopy, and endoscopic biopsies were false-negative repeatedly. This may be explained by the presence of cancer cells at the anastomotic line or trapping of cancer cells in the staple line, resulting in local recurrence, especially in patients who underwent double-staplinganastomosis[6,17].

Therefore, EUS-FNA gained the optimal diagnostic procedure and defined the proper treatment plan.

EUS can act not only as a method for the evaluation of precancerous polyps and subepithelial lesions found during screening of CRC, but also it has a great role in follow-up after resection of rectal carcinoma for early detection and tissue confirmation of locally recurrent cancer colon, by allowing the collection of specimens for histological and immuno-histochemical analysis, and overcoming some of the inherent user bias[18].

Assessment for LCRR is still problematic and may be very tricky, so we recommend using EUS-FNA to exclude local recurrence, since it could be deeply implanted and missed by routine imaging tools and colonoscopy.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: Egypt

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Hiep LT, Viet Nam; Jin ZD, China S-Editor: Wang LL L-Editor: Wang TQ P-Editor: Wang LL

| 1. | Young PE, Womeldorph CM, Johnson EK, Maykel JA, Brucher B, Stojadinovic A, Avital I, Nissan A, Steele SR. Early detection of colorectal cancer recurrence in patients undergoing surgery with curative intent: current status and challenges. J Cancer. 2014;5:262-271. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 95] [Article Influence: 8.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Cârţână ET, Pârvu D, Săftoiu A. Endoscopic ultrasound: current role and future perspectives in managing rectal cancer patients. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2011;20:407-413. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Cortet M, Grimault A, Cheynel N, Lepage C, Bouvier AM, Faivre J. Patterns of recurrence of obstructing colon cancers after surgery for cure: a population-based study. Colorectal Dis. 2013;15:1100-1106. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Van Rijn JC, Reistma JB, Stoker J. Polyp Miss Rate Determined by Tandem Colonoscopy: A Systematic Review. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:343-350. |

| 5. | Kim HG, Lee SH, Jeon SR. Clinical significance of the first surveillance colonoscopy after endoscopic early colorectal cancer removal. Hepatogastroenterol. 2013;60:1047-1052. |

| 6. | Beynon J, Mortensen NJ, Foy DM, Channer JL, Rigby H, Virjee J. The detection and evaluation of locally recurrent rectal cancer with rectal endosonography. Dis Colon Rectum. 1989;32:509-517. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Nakajima S. The Efficacy of the EUS for the Detection of Recurrent Disease in the Anastomosis of Colon. Diagn Ther Endosc. 2001;7:149-158. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Sasaki Y, Niwa Y, Hirooka Y, Ohmiya N, Itoh A, Ando N, Miyahara R, Furuta S, Goto H. The use of endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration for investigation of submucosal and extrinsic masses of the colon and rectum. Endoscopy. 2005;37:154-160. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2015. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65:5-29. |

| 10. | Pfi Ster DG, Benson AB 3rd, Somerfi eld MR. Clinical practice. Surveillance strategies aft er curative treatment of colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2375-2382. |

| 11. | Kjeldsen BJ, Kronborg O, Fenger C. The pattern of recurrent colorectalcancer in a prospective randomised study and the characteristics ofdiagnostic tests. Int J Colorectal Dis. 1997;12:329-334. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Woodward T, Menke D. Diagnosis of recurrent rectal carcinoma by EUS-guided fine-needle aspiration. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;51:223-225. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Hünerbein M, Totkas S, Moesta KT, Ulmer C, Handke T, Schlag PM. The role of transrectal ultrasound-guided biopsy in the postoperative follow-up of patients with rectal cancer. Surgery. 2001;129:164-169. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | National Comprehensive Cancer Network. [cited 20 April 2022]. Available from: www.nccn.org. |

| 15. | Rex DK, Boland CR, Dominitz JA, Giardiello FM, Johnson DA, Kaltenbach T, Levin TR, Lieberman D, Robertson DJ. Colorectal Cancer Screening: Recommendations for Physicians and Patients from the U.S. Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112:1016-1030. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 368] [Cited by in RCA: 477] [Article Influence: 59.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Kahi CJ, Boland CR, Dominitz JA, Giardiello FM, Johnson DA, Kaltenbach T, Lieberman D, Levin TR, Robertson DJ, Rex DK. Colonoscopy Surveillance after Colorectal Cancer Resection: Recommendations of the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer. Am J Gastroenterol. 2016;111:337-46; quiz 347. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 17. | Umpleby HC, Fermor B, Symes MO, Williamson RC. Viability of exfoliated colorectal carcinoma cells. Br J Surg. 1984;71:659-663. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 312] [Cited by in RCA: 304] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Law WL, Chu KW. Local recurrence following total mesorectal excision with double-stapling anastomosis for rectal cancers: analysis of risk factors. World J Surg. 2002;26:1272-1276. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |