Published online Jul 16, 2022. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v14.i7.443

Peer-review started: January 27, 2022

First decision: April 10, 2022

Revised: May 3, 2022

Accepted: June 20, 2022

Article in press: June 20, 2022

Published online: July 16, 2022

Processing time: 167 Days and 9.2 Hours

Treatment for severe acute severe pancreatitis (SAP) can significantly affect Health-related quality of life (HR-QoL). The effects of different treatment strategies such as endoscopic and surgical necrosectomy on HR-QoL in patients with SAP remain poorly investigated.

To critically appraise the available evidence on HR-QoL following surgical or endoscopic necrosectomy in patient with SAP.

A literature search was performed on PubMed, Google™ Scholar, the Cochrane Library, MEDLINE and Reference Citation Analysis databases for studies that investigated HR-QoL following surgical or endoscopic necrosectomy in patients with SAP. Data collected included patient characteristics, outcomes of interventions and HR-QoL-related details.

Eleven studies were found to have evaluated HR-QoL following treatment for severe acute pancreatitis including 756 patients. Three studies were randomized trials, four were prospective cohort studies and four were retrospective cohort studies with prospective follow-up. Four studies compared HR-QoL following surgical and endoscopic necrosectomy. Several metrics of HR-QoL were used including Short Form (SF)-36 and EuroQol. One randomized trial and one cohort study demonstrated significantly improved physical scores at three months in patients who underwent endoscopic necrosectomy compared to surgical necrosectomy. One prospective study that examined HR-QoL following surgical necrosectomy reported some deterioration in the functional status of the patients. On the other hand, a cohort study that assessed the long-term HR-QoL following sequential surgical necrosectomy stated that all patients had SF-36 > 60%. In the only study that examined patients following endoscopic necrosectomy, the HR-QoL was also very good. Three studies investigated the quality adjusted life years suggesting that endoscopic and surgical approaches to management of pancreatic necrosis were comparable in cost effectiveness. Finally, regarding HR-QoL between open necrosectomy and minimally invasive approaches, patients who underwent the later had a significantly better overall quality of life, vitality and mental health.

This review would suggest that the endoscopic approach might offer better HR-QoL compared to surgical necrosectomy. However, the available comparative literature was very limited. More randomized trials powered to detect differences in HR-QoL are required.

Core Tip: Acute pancreatitis is a common disease with potentially life-threatening complications. Treatment for severe acute pancreatitis can significantly affect health-related quality of life (HR-QoL). The effects of different treatment strategies such as endoscopic and surgical necrosectomy on HR-QoL remain poorly investigated. In this review, we critically analyze the available evidence on HR-QoL following treatment for severe acute pancreatitis. It could be suggested that endoscopic necrosectomy could offer better HR-QoL compared to surgical necrosectomy.

- Citation: Psaltis E, Varghese C, Pandanaboyana S, Nayar M. Quality of life after surgical and endoscopic management of severe acute pancreatitis: A systematic review. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2022; 14(7): 443-454

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v14/i7/443.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v14.i7.443

Acute pancreatitis is a common disease with potentially serious complications. Most patients present with a mild and self-limiting disease which is associated with low morbidity and mortality[1]. However, some patients present with moderate to severe or severe acute pancreatitis which can be complicated by organ failure and local complications such as pancreatic or peripancreatic necrosis[2-4]. Approximately, one third of these patients will develop infection of the necrosis which carries significant morbidity and mortality and will necessitate intervention[5,6].

Historically, open necrosectomy with debridement and post-operative lavage has been the treatment of choice[7]. In the last decade, the surgical step up-approach using a percutaneously inserted drain combined with minimally invasive necrosectomy has become increasingly popular and replaced open surgery as the standard approach[8,9]. As an alternative to surgery, endoscopic procedures for debridement of pancreatic necrosis have become increasingly popular as they offer significantly lower morbidity and mortality rates[10-14]. The endoscopic procedure can also be performed in a step-up approach only to be followed by surgical necrosectomy if endoscopic does not result in clinical improvement. However, there is no evidence to favor any of the surgical, minimally invasive, or endoscopic procedures as the better treatment of severe acute pancreatitis in terms of quality of life.

Traditionally, the outcome of different treatment strategies was determined only in terms of cure, morbidity and mortality[15]. However, in the era of patient-centered medicine, the health-related quality of life (HR-QoL) also needs to be considered[15]. HR-QoL is defined as the perceived physical and mental health of an individual over time. Several studies have investigated the effect of severe acute pancreatitis on HR-QoL and provided some contradictory results[16-22]. Hochman et al[19] as well as Symersky et al[20] reported the HR-QoL of patients with SAP was significantly impaired. On the other hand, Soran et al[18] and Halonen et al[23] stated that patients treated for SAP returned to normal activities. The number of studies that examined HR-QoL of patients with SAP who underwent necrosectomy either surgically or endoscopically is very limited. The aim of this systematic review was to identify and critically appraise the available studies evaluating HR-QoL in patients who underwent either surgical or endoscopic necrosectomy for SAP with necrosis.

A search for all relevant literature was performed on PubMed, Google™ Scholar, the Cochrane Library and MEDLINE databases in September 2021. The complete search strategy can be found in the Supple

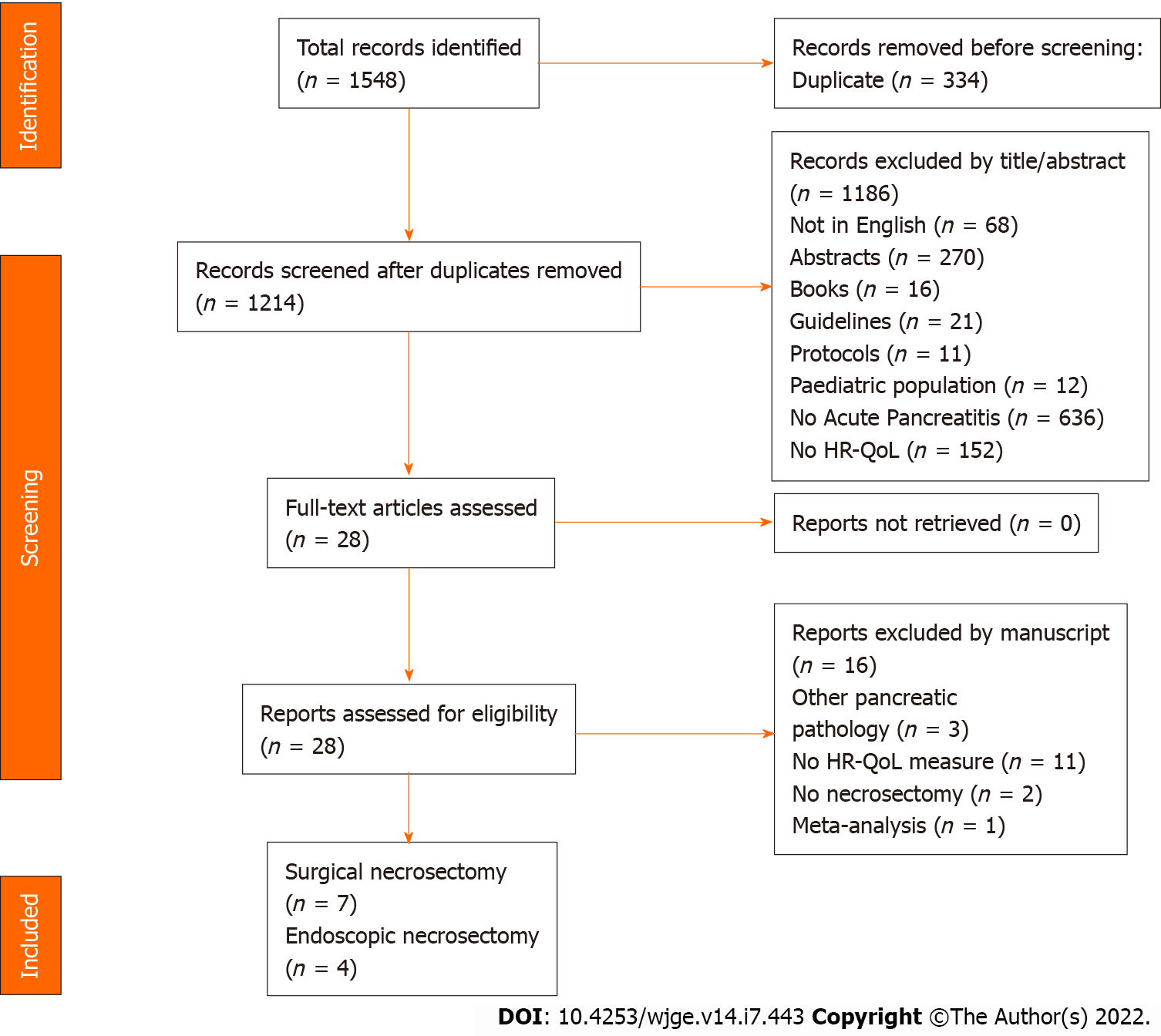

Studies identified through the search strategy were initially assessed for inclusion by the title and abstract and subsequently by full text review (EP). Studies were included when the outcome measure of HR-QoL was either a primary or secondary endpoint. Only studies reporting on adult patients who underwent necrosectomy for severe acute pancreatitis were included. Duplicate studies and populations were cross-referenced and removed. The bibliography of the included studies was also reviewed. Figure 1 demonstrates the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analysis (PRISMA) flow diagram[24].

Data were extracted by two independent reviewers (CV and EP) from the included studies with discrepancies resolved by a third (SP) reviewer. Data were collected on the details of each study (authors, year, level of evidence, study type, number of centres involved and country), patient characteristics within each study (sample size, diagnosis, mean age and gender), and HR-QoL details (QoL instruments used, scoring methodology, type of intervention, response and follow-up).

To assess bias (EP and CV) in the included randomized trials The Cochrane risk of bias tool for randomized control trials (RoB 2.0)[25] was used which focuses upon random sequence generation (selection bias), allocation concealment (selection bias), blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias), blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias), incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) and selective reporting (reporting bias). The risk of bias for the included observational studies was performed using the Risk of Bias In Non-randomized Studies – of Interventions (ROBINS-I) assessment tool[26]. This tool focuses upon confounding factors (confounding bias), selection bias, classification of interventions (classification bias), deviation from the intended interventions (performance bias), incomplete outcome data (attrition bias), blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) and selective reporting (reporting bias). Each study was ranked as low, moderate or high risk of bias based on these criteria (Tables 1 and 2).

| Ref. | Confounding | Selection bias | Bias in classification of interventions | Bias due to deviation from intended interventions | Incomplete outcome data | Blinding of outcome assessment | Selective reporting | Other bias |

| Seifert et al[27] | - | - | + | + | + | - | + | - |

| Smith et al[33] | + | + | ? | ? | - | - | + | - |

| Cinquepalmi et al[17] | ? | + | + | + | - | - | + | - |

| Fenton-Lee et al[29] | + | - | ? | + | + | - | - | - |

| Kriwanek et al[32] | ? | ? | - | ? | + | - | + | - |

| Reszetow et al[31] | + | ? | + | + | + | - | + | - |

| Broome et al[16] | - | ? | + | - | - | - | + | - |

| Tu et al[34] | ? | + | ? | + | + | - | + | - |

Overall, eleven studies were included of which most were from European centres (n = 7)[17,27-32]. Three studies were conducted in American centres[11,16,33] and one in Asia[34]. The studies were undertaken between 1993 and 2020 including an overall number of 756 patients. Three studies were randomized trials[11,28,30], four were prospective cohort studies[17,29,31,32], and four were retrospective cohort studies with prospective follow-up[16,27,33,34]. Only four studies compared surgical intervention to endoscopic intervention[11,27,28,34], while five studies investigated surgical approaches[16,17,29,30,32], and one study investigated endoscopic intervention alone[33]. Most studies were of cohorts with confirmed or suspected infected pancreatic or peripancreatic necrosis requiring intervention. Various metrics of HR-QoL were employed including Short Form (SF)-36[11,16,17,30,33-35], and EuroQol (EQ-5D)[28,30]. Time of administration of HR-QoL tools were variable ranging from 3 to 139 months. Other studies tended to use less known or custom, unvalidated measures of quality of life, limiting between study comparability[27,29,31]. Characteristics of the included studies are summarized in Table 3. A meta-analysis of the included studies was not possible because the populations, interventions, study designs, and outcomes reported varied significantly between studies.

| Ref. | Country | Hospital | Study design | Study interval | Treatment | Patient cohort | Relevant patients | Patients in study | Questionnaire | Assessment times |

| Broome et al[16], 1996 | USA | Duke University of Medical Centre | Retrospective with prospective follow-up | 1988 to 1994 | Surgery (operative debridement of necrosis) | Pancreatic necrosis | 40 surgically managed patients with pancreatic necrosis | 40 | SF-36 | Average follow-up 51 mo |

| Fenton-Lee et al[29], 1993 | UK | Greater Glasgow Health Board | Prospective | April 1991 to March 1992 | Surgery (required operative intervention); 9/10 also received endoscopic procedures | Pancreatic necrosis | 10; 10 operative intervention, 9/10 also endoscopic intervention | 10 | Rosser disability and distress index | Admission and follow-up |

| Kriwanek et al[32], 1998 | Austria | Rudolfstiftung-Hospital | Prospective | January 1 1988 to June 30 1996 | Surgery (open necrosectomy) | Pancreatic necrosis | 75; 57 survivors | 75 with pancreatic necrosis (72 other sources of intra-abdominal infection) | SF-36 | Not stated |

| Cinquepalmi et al[17], 2006 | Italy | Not reported | Prospective | 1990 to 2005 | Surgery (sequential surgical debridement) | Infected pancreatic necrosis | 35; all received sequential surgical debridement | 35 | SF-36 | Not reported |

| Reszetow et al[31], 2007 | Poland | Medical University of | Prospective | January 1993 to December 1999 | Surgery (Bradley procedure) | Infected pancreatic necrosis | 28; 44 (16.1%) of 274 patients with acute pancreatitis; 35/44 (63.4%) survivors for follow-up; 5 excluded | 44 | Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy scale | 24-96 mo |

| Seifert et al[27], 2009 | Germany | 6 centres | Retrospective with prospective follow-up | 1999 to 2005, follow-up 2004 to 2008 | Endoscopy vs surgery | Infected pancreatic necrosis | 93; 75 endoscopic; 18 failed, 11 surgery | 93 | Study-specific tool | Up to 24 mo |

| van Brunschot et al[28], 2017 | Netherlands | 19 centres | Randomized trial | September 20 2011 to January 29 2015 | Endoscopy vs surgery | Confirmed or suspected infected pancreatic or peripancreatic necrosis. | 98; 51 endoscopic and 47 surgical | 98 | EQ-5D-3L | 3 and 6 mo |

| Hollemans et al[30], 2019 | Netherlands | Randomized trial | November 2005 to October 2008 | Surgery (step-up approach (primary percutaneous catheter drainage, followed by, if necessary, minimally invasive retroperitneal necrosectomy) vs open necrosectomy | Confirmed or suspected infected pancreatic necrosis. | 60; 28/43 step-up approach (8 died), 32/45 open necrosectomy (7 died) | 88 | SF-36 and EuroQol | 3, 6, and 12 mo after discharge | |

| Smith et al[33], 2019 | USA | Barnes-Jewish Hospital/Washington University School of Medicine | Retrospective with prospective follow-up | January 2006 to May 2016 | Endoscopy | Walled off necrosis | 41 (returned QoL questionnaires) | 98 | SF-36 | Mean 37.4 (range 1-139) mo |

| Bang et al[11], 2020 | USA | Florida Hospital | Randomized trial | May 12 2014 to March 24 2017 | Endoscopy vs surgery | Confirmed or suspected infected pancreatic or peripancreatic necrosis. | 66; 34 endoscopic and 32 surgery | 66 | SF-36 | 3 and 6 mo |

| Tu et al[34], 2020 | China | Jinling Hospital, Medical School of Nanjing University | Retrospective with prospective follow-up | January 2000 to February 2015 | Surgery (open necrosectomy) vs minimally invasive drainage | Infected pancreatic necrosis | 109; 101 included in analysis (61 minimally invasive drainage, 40 open necrosectomy) | 109 | SF-36 | Not stated |

Four studies compared HR-QoL between patients who underwent endoscopic and surgical interventions of which two were randomized trials[11,28] and two were retrospective cohorts[27,34]. In Bang et al[11]’s randomized trial 34 patients underwent endoscopic necrosectomy and 32 patients underwent minimally invasive surgical necrosectomy for necrotizing pancreatitis. It was reported that the physical component scores for the endoscopic treatment group were significantly improved at 3 months compared to the surgical treatment group (P = 0.39)[11]. In terms of quality adjusted life-years (QALYs) per patient, Bang et al reported that QALY gained for endoscopy was 0.452 (BCa 95%CI, 0.434-0.472) compared with 0.450 (BCa 95%CI, 0.427-0.468) for surgery, which translates to a mean difference (MD) of -0.002 (95%CI, 0.029-0.025)[11]. Similarly in van Brunschot et al[28]’s randomized trial, the QALY gained for endoscopy was 0.452 (BCa 95%CI, 0.434-0.472) compared with 0.450 (BCa 95%CI, 0.427-0.468) for surgery; with a MD of -0.002 (95%CI, 0.029-0.025).

In the GEPARD Study, 75 patients with pancreatic or peripancreatic necrosis were successfully treated endoscopically[27]. Forty-eight of these patients also showed radiological success as there was no evidence of residual necrosis or cyst on the day of discharge[27]. Eleven of those 75 patients had recurrent pancreatic necrosis, 1 patient had a pancreatitis-related death and 6 non-pancreatitis related deaths at long-term follow-up[27]. This was compared to 18 patients who failed endoscopic therapy, of whom 7 patients died secondary to pancreatitis and 11 progressed to surgery[27]. Of those that progressed to surgery, 8 were successful and 3 had recurrences of pancreatic necrosis[27]. At a mean follow-up of 50 months (range 50-96 months) among 68 patients who underwent successful endoscopic therapy and at a mean follow-up of 53 months (range (15-93 months) among 11 patients that successful surgical treatment; 32 (47%) vs 4 (46%) were still working, 31 (46%) vs 6 (55%) were retired, and only 5 (7%) vs 1 (9%) retired due to disease[27]. A higher proportion of patients reported difficulties with carrying heavier loads (36% vs 28%), walking around the block (27% vs 10%), leaving the house (9% vs 7%) who underwent surgical compared to endoscopic therapy[27]. After successful endoscopic necrosectomy more patients had to change their diet (62% vs 36%) compared to surgical intervention[27]. On self-assessment those that underwent initial successful endoscopic therapy had improved physical scores (2.47 range 0-10) and quality of life (2.35 range 0-10) compared to those that had surgery after failed endoscopic therapy (physical condition 3.82 range 0-10; quality of life 3.54 range 0-10)[27].

Tu et al[34] reports a similar cohort of 101 patients with infected pancreatic necrosis of which 61 underwent minimally invasive drainage (which included percutaneous catheter drainage, negative pressure irrigation or endoscopic necrosectomy) and 40 patients that underwent open necrosectomy. The overall quality of life score was significantly higher in the cohort of infected necrosis patients who underwent minimally invasive drainage compared to open necrosectomy (mean 125 ± 13 vs 116 ± 17, P = 0.005)[34]. The quality-of-life domains measured by the SF-36 were comparable between these groups with respect to physical functioning, physical role, but mental health scores were significantly better in minimally invasive drainage group[34].

In a study that assessed HR-QoL in a cohort of 35 patients who underwent sequential surgical necrosectomy for infected pancreatic necrosis, all patients had an SF-36 > 60%, and 78% had scores > 70%-80% suggesting overall good quality of life[17]. Quality of life was notably poorer amongst those with alcoholic pancreatitis. Similarly, 12/32 were able to return to employment within 6 months[17]. Comparably, in another study, 50/57 (88%) patients who underwent open surgical intervention for pancreatic necrosis also had good quality of life[32]. However, in this same cohort 9 patients (16%) experienced worsened employment status[32]. In Smith et al[33]’s cohort of 41 patients who underwent endoscopic management of walled-off necrosis, the mean SF-36 general health score was 56.93 (SD 25.82).

In a cohort of 80 patients that underwent endoscopic management of walled-off pancreatic necrosis, of whom 41 responded to an SF-36 questionnaire; the mean SF-36 score for physical functioning was 82.32 (standard deviation (SD) 18.24), and 58.54 (SD 40.93) for physical role[33]. This was comparable to Broome et al[16]’s cohort of 40 patients with pancreatic necrosis managed via surgical debridement with slightly lower physical functioning and physical role SF-36 scores than age-matched controls. In Kriwanek et al[32]’s surgically managed cohort, only 2/57 (4%) of patients experienced deteriorated functional status as per SF-36. Several studies compared physical component scores of the SF-36 at 3-months and 6-months[11,30,33]. Compared to surgical approach, patients who had endoscopic management of necrotizing pancreatitis had improved physical component scores at discharge, at 3 months, and at 6 months[11,28]. In Holleman et al[30]’s randomized trial of step-up approach vs straight to open necrosectomy in patients with necrotizing pancreatitis there were no significant differences in the Dutch nor US standard versions of the SF-36 physical health scores between approaches, with scores in both groups being between 42 and 44. These similarities persisted at longer follow-ups[30].

Smith et al[33] reports in a cohort of 41 patients that underwent endoscopic management of walled of necrosis an SF-36 mental health score of 79.61 (SD 18.52). Only Kriwanek et al[32]’s cohort of 57 patients that underwent open surgical intervention for severe intra-abdominal infection and pancreatic necrosis reported on psychosocial functioning and 6 patients (10%) showed depressive mood and 17 (30%) had impaired activity. In contrast to physical function, Bang et al[11] found endoscopic intervention compared to surgical intervention was not significantly associated with the mental component score of the SF-36. Broome et al[16] found SF-36 mental health scores were comparable between surgically managed patients with necrosis and age-matched controls. Tu et al[34]’s cohort also demonstrated improved mental health scores among those who underwent minimally invasive drainage. Similar to the physical functioning, the mental component of the SF-36 questionnaire was similar at baseline and throughout follow-up between step-up approaches and open necrosectomy approaches to necrotizing pancreatitis[30].

Smith et al[33] demonstrated an SF-36 mean bodily pain score of 75.54 (SD 22.78) after endoscopic management of walled-off pancreatic necrosis. This was very comparable to a similar cohort of 40 patients managed with surgical debridement, which in turn was found to be similar to age-matched controls[16]. These findings of equivalence regarding pain between endoscopic and surgical management was further corroborated by Tu et al[34]. In another study, 43/57 (75%) patients who underwent open surgical intervention for pancreatic necrosis showed no pain[32].

Smith et al[33]’s cohort of 41 patients with follow-up SF-36 questionnaires after endoscopic management of walled off necrosis reported on the separate domains of the SF-36 HR-QoL measure. Patients’ mean vitality scores were 56.83 (SD 23.89), social function scores were 83.84 (SD 20.96), and emotional role scores were 82.30 (SD 34.20). Vitality, social functioning, and emotional role SF-36 scores measured by Smith et al[33], were comparable to the scores reported in Broome et al[16]’ cohort of surgically managed patients with pancreatic necrosis. Tu et al[34] was the only remaining cohort which compared these SF-36 domains between surgically managed and endoscopically (minimally invasive drainage) managed patients. It was reported that both social and emotional role functioning were significantly better in the minimally invasive group of patients[34].

Smith et al[33] reports that pancreatic exocrine insufficiency (PEI) was the only factor predictive of lower SF-36 scores; and this was true for both the mental and physical components scores. This translated to lower physical role, vitality, emotional role, and mental health scores if patients had PEI[33]. In a randomized trial comparing step-up approach vs open necrosectomy for management of necrotizing pancreatitis, they found both approaches were comparable in terms of quality of life[30]. However, quality of life was lower if patients reported abdominal pain, and they did not find PEI (nor pancreatic endocrine function) to affect this[30]. In Cinquepalmi et al[17]’s cohort of patients with infected pancreatic necrosis managed with sequential surgical debridement, alcoholic etiology was the only factor associated with poorer SF-36 scores. In contrast, in Reszetow et al[31]’s cohort of 24 patients treated with the Bradley procedure for infected pancreatic necrosis, there was no difference in quality of life between those with biliary and alcoholic etiologies.

The debridement of pancreatic necrosis remains very challenging for both patients and clinicians as it can have a significant impact on HR-QOL[36,37]. To the best of our knowledge this is the first systematic review to assess HR-QoL following surgical or endoscopic necrosectomy in patients with SAP. Despite the advancements in treatment strategies and the various as well as fundamentally different techniques of necrosectomy, the published data on HR-QoL following each procedure is very limited.

The present review included 11 studies of which 3 were randomized trials[11,28,30] and only four studies compared surgical intervention to endoscopic intervention[11,27,28]. In the overall quality of life following endoscopic intervention vs surgical intervention, Bang et al[11] reported significantly improved physical component scores for the endoscopic treatment group at the 3-mo follow-up. The authors attributed this to factors such as the shorter duration of the endoscopic procedure, faster resolution of SIRS, fewer disease-related adverse events and shorter length of stay to intensive care unit[11,14,38,39]. In a similar way, patients who were managed endoscopically had improved physical component scores at discharge, at 3 mo, and at 6 mo, whereas Kriwanek et al[32] reported that a small number of patients experienced deteriorated functional status following surgical necrosectomy[11,32]. In contrary to Bang et al[11], Seifert et al[27] stated that less patients reported difficulties in carrying heavy loads, walking around the block or needed to modify their diet following surgical necrosectomy. However, employment status was slightly better in the group of patients who were treated endoscopically[27]. In terms of HR-QoL between patients who underwent open necrosectomy and minimally invasive necrosectomy of the necrotic parenchyma, Tu et al[34] reported a significantly better total quality of life as well as vitality and mental health scores following minimally invasive necrosectomy. On the other hand, there was no difference in the physical functioning and bodily pain scores between the two groups of patients. The authors stated that minimally invasive necrosectomy involved a series of procedures that included endoscopic necrosectomy via a tract between the stomach and the cavity containing the necrotic parenchyma[34]. The reported results were attributed to pancreatic complications that the open necrosectomy group of patients suffered from[34].

In both randomized trials by Bang et al[11] and van Brunschot et al[28], the QALY gained following endoscopic necrosectomy was very similar to that following surgical necrosectomy. In terms of mental health, Bang et al[11] did not demonstrate any difference in the mental health component of the SF-36 between patients who underwent surgical or endoscopic intervention. However, Kriwanek et al[32] reported that 10% of the patients had depressive mood following surgical necrosectomy. With regards to other elements of quality of life, the vitality, social and emotional scores were very good following endoscopic necrosectomy indicating that most patients recovered fully without lasting effects[33]. Patients following open necrosectomy were found to have no pain[32].

Based on this review it is difficult to assess which type of intervention offers the best HR-QoL in patients with severe acute pancreatitis. At present, the strongest evidence has been published by Bang et al[11] and favors endoscopic necrosectomy as the treatment of choice. However, all three randomized trials included in this review as well the rest of the included studies were underpowered. Moreover, the lumen apposing metal stents were introduced to clinical practice while the studies by Bang et al[11] and Smith et al[33] were in progress. Even though this technique was used in some of the patients, it contributed to the heterogenicity of different endoprostheses that were used. Therefore, more comparative and adequately powered studies are still needed to accurately assess the quality of life following each technique.

None of the included studies assessed the quality of life of the patients while they were hospitalized and therefore the immediate effects of each approach for pancreatic debridement remain unknown. Also, five of the included studies assessed the short-term effect (< 12 mo) and only two studies the long-term effect (> 24 months) while three studies have not stated the intervals or the duration of follow-up. Therefore, even though the SF-36 was designed to primarily assess the long- term effects of a chronic condition[40], the long-term effects of each method of debridement remain grossly unknown.

The SF-36 questionnaire may be a good tool to evaluate HR-QoL and demonstrate the presence of significant changes, but subtle changes might require a different assessment tool to be appreciated. However, other available HR-QoL assessment tools have been compared with the SF-36 and they do not seem to be more accurate[41]. In the era of patient-centered medicine, HR-QoL is regarded as one of cornerstones of the "goal-oriented patient care outcomes" concept[15]. Interestingly, there was significant inconsistency in the use of HR-QoL assessment tools in the included studies. Six out of 10 studies used the SF-36 tool whereas the rest four used either a different or a study-specific tool. This inconsistency made it impossible to safely compare the reported results from different studies and accurately extract outcomes on which treatment approach offers the best outcome. To the best of our knowledge there is no published guidance in the field of pancreatic surgery that recommends a specific tool for HR-QoL assessment. Therefore, the creation of a new tool to evaluate patient reported HR-QoL outcome in patients with pancreatic pathology or even more specifically for acute pancreatitis will deliver a more reliable assessment of different treatment modalities and how they affect the HR-QoL in the sort-, medium- and long-term follow-up period.

The present systematic review has several limitations. The majority of the included studies were observational in nature which might have introduced bias due to confounding. It would be useful if future randomized trials were designed in such a way that HR-QoL was one of the study outcomes. Moreover, the quantitative analysis was challenging to perform due to the various HR-QoL metrics as well as the different timing of administration of the different tools that were employed in the included studies. As mentioned earlier, the SF-36 was originally conceived to evaluate HR-QoL in chronic conditions over a long-term follow-up while three studies in this review have used it to assess short-term follow-up in an acute condition. Another significant limitation of this review was the heterogeneity of the patients among the included studies both in terms of age and severity of the condition as well as the cause of pancreatitis.

This systematic review would indicate that the endoscopic approach should be the preferred method for pancreatic necrosectomy. However, more randomized trials in patients with severe acute pancreatitis are needed with HR-QoL as primary endpoint. The goal is to achieve a person-centered coordinated care; through patient reported experience and outcome measures. These instruments are being reported with increasing frequency in the recent years for their ability to bridge the gap between the perceptions of the clinician and patients. This information is then used to adjust treatment and care and to achieve better results, enhance adherence, increase patient satisfaction & quality of life. Finally, it would be useful to create a disease specific HR-QoL assessment tool for acute pancreatitis that will allow comparison of different management options and how they impact the HR-QoL.

Treatment for severe acute pancreatitis (SAP) can significantly affect health related quality of life (HR-QoL). However, the effects of different treatment strategies such as surgical, minimally invasive or endoscopic necrosectomy, on HR-QoL remain poorly investigated. Therefore, there is no evidence to favor any of the existing approaches as the better treatment of SAP in terms of quality of life. To the best of our knowledge this is the first systematic review to assess HR-QoL following pancreatic necrosectomy in patients with SAP.

Traditionally, open necrosectomy has been the standard approach for patients with SAP and necrosis of pancreatic parenchyma. This was followed by the introduction of surgical step up-approach combined with minimally invasive necrosectomy as the treatment of choice. More recently, endoscopic necrosectomy has gained popularity as it offers significantly lower morbidity and mortality rates. However, in the era of patient-centered medicine, HR-QoL also needs to be considered. Unfortunately, there is no clear evidence to favor any of these procedures as the better treatment of SAP in terms of quality of life.

The objective of this study was to critically appraise the published evidence on HR-QoL in patients with SAP who underwent surgical or endoscopic necrosectomy.

A literature search was performed on several databases for studies that examined the HR-QOL following necrosectomy in adult patients with SAP. Studies published in English were excluded due to limited resources. Data were collected on the details of each study, patient characteristics as well as HR-QoL. The Cochrane risk of bias tool for randomized control trials (RoB 2.0) was used to assess bias in the included randomized studies whereas the Risk of Bias In Non-randomized Studies – of Interventions (ROBINS-I) was used to asses bias in the included observational studies.

Eleven studies evaluated HR-QoL following necrosectomy including 756 patients. Three studies were randomized trials and eight were cohort studies. One randomized trial and one cohort study demonstrated significantly improved physical scores at three months in patients who underwent endoscopic necrosectomy compared to surgical necrosectomy. In the only study that examined patients following endoscopic necrosectomy, the HR-QoL was also very good. Two randomized trials and one cohort study investigated the quality adjusted life years suggesting that endoscopic and surgical necrosectomy were comparable in cost effectiveness. When open necrosectomy was compared with minimally invasive approaches, patients who underwent the later reported better overall quality of life, vitality and mental health.

This study would suggest that the endoscopic approach should be the preferred method for pancreatic necrosectomy as it might offer better HR-QoL. However, more randomized trials powered to detect differences in HR-QoL are still required.

Future research should aim to provide the tools for a person-centered coordinated care through a patient reported experience and outcome measures. This will improve results, adherence, patient satisfaction and quality of life. It is also important to create a disease specific HR-QoL questionnaire for acute pancreatitis to allow evaluation of different management strategies and the impact they have on HR-QoL.

Provenance and peer review: Invited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Surgery

Country/Territory of origin: United Kingdom

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Demirli Atici S, Turkey; Fru PN, South Africa A-Editor: Zhu JQ, China S-Editor: Liu JH L-Editor: A P-Editor: Liu JH

| 1. | van Dijk SM, Hallensleben NDL, van Santvoort HC, Fockens P, van Goor H, Bruno MJ, Besselink MG; Dutch Pancreatitis Study Group. Acute pancreatitis: recent advances through randomised trials. Gut. 2017;66:2024-2032. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 221] [Cited by in RCA: 294] [Article Influence: 36.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Banks PA, Freeman ML; Practice Parameters Committee of the American College of Gastroenterology. Practice guidelines in acute pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:2379-2400. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1181] [Cited by in RCA: 1148] [Article Influence: 60.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Banks PA, Bollen TL, Dervenis C, Gooszen HG, Johnson CD, Sarr MG, Tsiotos GG, Vege SS; Acute Pancreatitis Classification Working Group. Classification of acute pancreatitis--2012: revision of the Atlanta classification and definitions by international consensus. Gut. 2013;62:102-111. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4932] [Cited by in RCA: 4298] [Article Influence: 358.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (44)] |

| 4. | Portelli M, Jones CD. Severe acute pancreatitis: pathogenesis, diagnosis and surgical management. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2017;16:155-159. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 99] [Article Influence: 12.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | van Santvoort HC, Bakker OJ, Bollen TL, Besselink MG, Ahmed Ali U, Schrijver AM, Boermeester MA, van Goor H, Dejong CH, van Eijck CH, van Ramshorst B, Schaapherder AF, van der Harst E, Hofker S, Nieuwenhuijs VB, Brink MA, Kruyt PM, Manusama ER, van der Schelling GP, Karsten T, Hesselink EJ, van Laarhoven CJ, Rosman C, Bosscha K, de Wit RJ, Houdijk AP, Cuesta MA, Wahab PJ, Gooszen HG; Dutch Pancreatitis Study Group. A conservative and minimally invasive approach to necrotizing pancreatitis improves outcome. Gastroenterology. 2011;141:1254-1263. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 460] [Cited by in RCA: 464] [Article Influence: 33.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 6. | Leppäniemi A, Tolonen M, Tarasconi A, Segovia-Lohse H, Gamberini E, Kirkpatrick AW, Ball CG, Parry N, Sartelli M, Wolbrink D, van Goor H, Baiocchi G, Ansaloni L, Biffl W, Coccolini F, Di Saverio S, Kluger Y, Moore E, Catena F. 2019 WSES guidelines for the management of severe acute pancreatitis. World J Emerg Surg. 2019;14:27. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 538] [Cited by in RCA: 419] [Article Influence: 69.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Kyte D, Ives J, Draper H, Calvert M. Current practices in patient-reported outcome (PRO) data collection in clinical trials: a cross-sectional survey of UK trial staff and management. BMJ Open. 2016;6:e012281. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | van Santvoort HC, Besselink MG, Bakker OJ, Hofker HS, Boermeester MA, Dejong CH, van Goor H, Schaapherder AF, van Eijck CH, Bollen TL, van Ramshorst B, Nieuwenhuijs VB, Timmer R, Laméris JS, Kruyt PM, Manusama ER, van der Harst E, van der Schelling GP, Karsten T, Hesselink EJ, van Laarhoven CJ, Rosman C, Bosscha K, de Wit RJ, Houdijk AP, van Leeuwen MS, Buskens E, Gooszen HG; Dutch Pancreatitis Study Group. A step-up approach or open necrosectomy for necrotizing pancreatitis. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1491-1502. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1038] [Cited by in RCA: 1026] [Article Influence: 68.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Sorrentino L, Chiara O, Mutignani M, Sammartano F, Brioschi P, Cimbanassi S. Combined totally mini-invasive approach in necrotizing pancreatitis: a case report and systematic literature review. World J Emerg Surg. 2017;12:16. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Bang JY, Holt BA, Hawes RH, Hasan MK, Arnoletti JP, Christein JD, Wilcox CM, Varadarajulu S. Outcomes after implementing a tailored endoscopic step-up approach to walled-off necrosis in acute pancreatitis. Br J Surg. 2014;101:1729-1738. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Bang JY, Arnoletti JP, Holt BA, Sutton B, Hasan MK, Navaneethan U, Feranec N, Wilcox CM, Tharian B, Hawes RH, Varadarajulu S. An Endoscopic Transluminal Approach, Compared With Minimally Invasive Surgery, Reduces Complications and Costs for Patients With Necrotizing Pancreatitis. Gastroenterology. 2019;156:1027-1040.e3. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 255] [Cited by in RCA: 219] [Article Influence: 36.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Gluck M, Ross A, Irani S, Lin O, Gan SI, Fotoohi M, Hauptmann E, Crane R, Siegal J, Robinson DH, Traverso LW, Kozarek RA. Dual modality drainage for symptomatic walled-off pancreatic necrosis reduces length of hospitalization, radiological procedures, and number of endoscopies compared to standard percutaneous drainage. J Gastrointest Surg. 2012;16:248-56; discussion 256. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 119] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Gardner TB, Coelho-Prabhu N, Gordon SR, Gelrud A, Maple JT, Papachristou GI, Freeman ML, Topazian MD, Attam R, Mackenzie TA, Baron TH. Direct endoscopic necrosectomy for the treatment of walled-off pancreatic necrosis: results from a multicenter U.S. series. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;73:718-726. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 218] [Cited by in RCA: 205] [Article Influence: 14.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Bakker OJ, van Santvoort HC, van Brunschot S, Geskus RB, Besselink MG, Bollen TL, van Eijck CH, Fockens P, Hazebroek EJ, Nijmeijer RM, Poley JW, van Ramshorst B, Vleggaar FP, Boermeester MA, Gooszen HG, Weusten BL, Timmer R; Dutch Pancreatitis Study Group. Endoscopic transgastric vs surgical necrosectomy for infected necrotizing pancreatitis: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2012;307:1053-1061. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 506] [Cited by in RCA: 495] [Article Influence: 38.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Sacristán JA. Patient-centered medicine and patient-oriented research: improving health outcomes for individual patients. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2013;13:6. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 140] [Cited by in RCA: 163] [Article Influence: 13.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Broome AH, Eisen GM, Harland RC, Collins BH, Meyers WC, Pappas TN. Quality of life after treatment for pancreatitis. Ann Surg. 1996;223:665-70; discussion 670. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Cinquepalmi L, Boni L, Dionigi G, Rovera F, Diurni M, Benevento A, Dionigi R. Long-term results and quality of life of patients undergoing sequential surgical treatment for severe acute pancreatitis complicated by infected pancreatic necrosis. Surg Infect (Larchmt). 2006;7 Suppl 2:S113-S116. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Soran A, Chelluri L, Lee KK, Tisherman SA. Outcome and quality of life of patients with acute pancreatitis requiring intensive care. J Surg Res. 2000;91:89-94. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Hochman D, Louie B, Bailey R. Determination of patient quality of life following severe acute pancreatitis. Can J Surg. 2006;49:101-106. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Symersky T, van Hoorn B, Masclee AA. The outcome of a long-term follow-up of pancreatic function after recovery from acute pancreatitis. JOP. 2006;7:447-453. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Szentkereszty Z, Agnes C, Kotán R, Gulácsi S, Kerekes L, Nagy Z, Czako D, Sápy P. Quality of life following acute necrotizing pancreatitis. Hepatogastroenterology. 2004;51:1172-1174. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Wright SE, Lochan R, Imrie K, Baker C, Nesbitt ID, Kilner AJ, Charnley RM. Quality of life and functional outcome at 3, 6 and 12 months after acute necrotising pancreatitis. Intensive Care Med. 2009;35:1974-1978. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Halonen KI, Pettilä V, Leppäniemi AK, Kemppainen EA, Puolakkainen PA, Haapiainen RK. Long-term health-related quality of life in survivors of severe acute pancreatitis. Intensive Care Med. 2003;29:782-786. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG; PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000097. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 52948] [Cited by in RCA: 46988] [Article Influence: 2936.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Sterne JAC, Savović J, Page MJ, Elbers RG, Blencowe NS, Boutron I, Cates CJ, Cheng HY, Corbett MS, Eldridge SM, Emberson JR, Hernán MA, Hopewell S, Hróbjartsson A, Junqueira DR, Jüni P, Kirkham JJ, Lasserson T, Li T, McAleenan A, Reeves BC, Shepperd S, Shrier I, Stewart LA, Tilling K, White IR, Whiting PF, Higgins JPT. RoB 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2019;366:l4898. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6581] [Cited by in RCA: 14926] [Article Influence: 2487.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Sterne JA, Hernán MA, Reeves BC, Savović J, Berkman ND, Viswanathan M, Henry D, Altman DG, Ansari MT, Boutron I, Carpenter JR, Chan AW, Churchill R, Deeks JJ, Hróbjartsson A, Kirkham J, Jüni P, Loke YK, Pigott TD, Ramsay CR, Regidor D, Rothstein HR, Sandhu L, Santaguida PL, Schünemann HJ, Shea B, Shrier I, Tugwell P, Turner L, Valentine JC, Waddington H, Waters E, Wells GA, Whiting PF, Higgins JP. ROBINS-I: a tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. BMJ. 2016;355:i4919. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7683] [Cited by in RCA: 10700] [Article Influence: 1188.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 27. | Seifert H, Biermer M, Schmitt W, Jürgensen C, Will U, Gerlach R, Kreitmair C, Meining A, Wehrmann T, Rösch T. Transluminal endoscopic necrosectomy after acute pancreatitis: a multicentre study with long-term follow-up (the GEPARD Study). Gut. 2009;58:1260-1266. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 333] [Cited by in RCA: 305] [Article Influence: 19.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | van Brunschot S, van Grinsven J, van Santvoort HC, Bakker OJ, Besselink MG, Boermeester MA, Bollen TL, Bosscha K, Bouwense SA, Bruno MJ, Cappendijk VC, Consten EC, Dejong CH, van Eijck CH, Erkelens WG, van Goor H, van Grevenstein WMU, Haveman JW, Hofker SH, Jansen JM, Laméris JS, van Lienden KP, Meijssen MA, Mulder CJ, Nieuwenhuijs VB, Poley JW, Quispel R, de Ridder RJ, Römkens TE, Scheepers JJ, Schepers NJ, Schwartz MP, Seerden T, Spanier BWM, Straathof JWA, Strijker M, Timmer R, Venneman NG, Vleggaar FP, Voermans RP, Witteman BJ, Gooszen HG, Dijkgraaf MG, Fockens P; Dutch Pancreatitis Study Group. Endoscopic or surgical step-up approach for infected necrotising pancreatitis: a multicentre randomised trial. Lancet. 2018;391:51-58. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 366] [Cited by in RCA: 469] [Article Influence: 67.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Fenton-Lee D, Imrie CW. Pancreatic necrosis: assessment of outcome related to quality of life and cost of management. Br J Surg. 1993;80:1579-1582. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Hollemans RA, Bakker OJ, Boermeester MA, Bollen TL, Bosscha K, Bruno MJ, Buskens E, Dejong CH, van Duijvendijk P, van Eijck CH, Fockens P, van Goor H, van Grevenstein WM, van der Harst E, Heisterkamp J, Hesselink EJ, Hofker S, Houdijk AP, Karsten T, Kruyt PM, van Laarhoven CJ, Laméris JS, van Leeuwen MS, Manusama ER, Molenaar IQ, Nieuwenhuijs VB, van Ramshorst B, Roos D, Rosman C, Schaapherder AF, van der Schelling GP, Timmer R, Verdonk RC, de Wit RJ, Gooszen HG, Besselink MG, van Santvoort HC; Dutch Pancreatitis Study Group. Superiority of Step-up Approach vs Open Necrosectomy in Long-term Follow-up of Patients With Necrotizing Pancreatitis. Gastroenterology. 2019;156:1016-1026. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 110] [Cited by in RCA: 148] [Article Influence: 24.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Reszetow J, Hać S, Dobrowolski S, Stefaniak T, Wajda Z, Gruca Z, Sledziński Z, Studniarek M. Biliary versus alcohol-related infected pancreatic necrosis: similarities and differences in the follow-up. Pancreas. 2007;35:267-272. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Kriwanek S, Armbruster C, Dittrich K, Beckerhinn P, Schwarzmaier A, Redl E. Long-term outcome after open treatment of severe intra-abdominal infection and pancreatic necrosis. Arch Surg. 1998;133:140-144. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Smith ZL, Gregory MH, Elsner J, Alajlan BA, Kodali D, Hollander T, Sayuk GS, Lang GD, Das KK, Mullady DK, Early DS, Kushnir VM. Health-related quality of life and long-term outcomes after endoscopic therapy for walled-off pancreatic necrosis. Dig Endosc. 2019;31:77-85. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Tu J, Zhang J, Yang Y, Xu Q, Ke L, Tong Z, Li W, Li J. Comparison of pancreatic function and quality of life between patients with infected pancreatitis necrosis undergoing open necrosectomy and minimally invasive drainage: A long-term study. Exp Ther Med. 2020;20:75. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Bellin MD, Kerdsirichairat T, Beilman GJ, Dunn TB, Chinnakotla S, Pruett TL, Radosevich DR, Schwarzenberg SJ, Sutherland DE, Arain MA, Freeman ML. Total Pancreatectomy With Islet Autotransplantation Improves Quality of Life in Patients With Refractory Recurrent Acute Pancreatitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14:1317-1323. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Thompson D, Bolourani S, Giangola M. Surgical Management of Necrotizing Pancreatitis. In: Recent Advances in Pancreatitis. Intech Open. 2022;. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 37. | Bugiantella W, Rondelli F, Boni M, Stella P, Polistena A, Sanguinetti A, Avenia N. Necrotizing pancreatitis: A review of the interventions. Int J Surg. 2016;28 Suppl 1:S163-S171. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Cirocchi R, Trastulli S, Desiderio J, Boselli C, Parisi A, Noya G, Falconi M. Minimally invasive necrosectomy versus conventional surgery in the treatment of infected pancreatic necrosis: a systematic review and a meta-analysis of comparative studies. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2013;23:8-20. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Strøm T, Martinussen T, Toft P. A protocol of no sedation for critically ill patients receiving mechanical ventilation: a randomised trial. Lancet. 2010;375:475-480. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 602] [Cited by in RCA: 570] [Article Influence: 38.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Ware JE Jr. SF-36 health survey update. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2000;25:3130-3139. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2485] [Cited by in RCA: 2861] [Article Influence: 114.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | John E. Ware. SF-36 HealthSurvey: Manual and Interpretation Guide. QualityMetric Incorporated 2005. |