Published online May 16, 2022. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v14.i5.342

Peer-review started: January 15, 2022

First decision: March 8, 2022

Revised: March 9, 2022

Accepted: April 15, 2022

Article in press: April 15, 2022

Published online: May 16, 2022

Processing time: 120 Days and 14.7 Hours

In order to successfully manage traumatic pancreatic duct (PD) leaks, early diagnosis and operative management is paramount in reducing morbidity and mortality. In the acute setting, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) can be a useful, adjunctive modality during exploratory laparotomy. ERCP with sphincterotomy and stent placement improves preferential drainage in the setting of injury, allowing the pancreatic leak to properly heal. However, data in this acute setting is limited.

In this case series, a 27-year-old male and 16-year-old female presented with PD leaks secondary to a gunshot wound and blunt abdominal trauma, respectively. Both underwent intraoperative ERCP within an average of 5.9 h from time of presentation. A sphincterotomy and plastic pancreatic stent placement was performed with a 100% technical and clinical success. There were no associated immediate or long-term complications. Following discharge, both patients underwent repeat ERCP for stent removal with resolution of ductal injury.

These experiences further demonstrated that widespread adaption and optimal timing of ERCP may improve outcomes in trauma centers.

Core Tip: In the acute setting, intraoperative endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) can effectively diagnosis and manage pancreatic duct (PD) injuries with stenting. At our high-volume trauma center, the on call therapeutic endoscopy team allows for quick and effective mobilization of resources. In this series, the time from admission to ERCP occurred within 6.3 and 5.6 h. The pancreatic injuries healed, and both stents were removed. In cases of traumatic PD injury, we believe that advanced gastroenterology care has the opportunity to improve the timing of diagnosis and treatment as a means to potentially reduce the morbidity and mortality associated with such injuries.

- Citation: Canakis A, Kesar V, Hudspath C, Kim RE, Scalea TM, Darwin P. Intraoperative endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography for traumatic pancreatic ductal injuries: Two case reports. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2022; 14(5): 342-350

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v14/i5/342.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v14.i5.342

Pancreatic duct (PD) injuries are uncommon (occurring in 3% to 12% of traumas), primarily due its protective retroperitoneal location. They can be difficult to diagnose due to non-specific symptoms and delayed findings on imaging[1]. A delay in diagnosis can result in severe complications, such as a pancreatic fistula, hemorrhage, or abscess by which obtaining a fast and accurate diagnosis is paramount[2,3].

Standard therapy for high grade pancreatic injury with traumatic PD disruption is operative. As the duct itself is not amenable to repair, surgical options are resection and/or simple drainage accepting the inevitable pancreatic fistula. Major pancreatic resection is morbid and can produce nutritional cripples and render patients diabetic. Preoperative imaging is often inaccurate or not feasible. The limited sensitivity (52%) of computed topography (CT) is further complicated by timing, as CT scans performed in less than 24 h of presentation can often miss PD injuries as inflammatory associated changes are yet to manifest[1,4,5]. There is also poor sensitivity associated with magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) imaging, and many times unstable patients may not be suitable for such imaging[4,6].

The diagnosis of PD transection is often suspected at the time of laparotomy. Knowing whether the PD is actually transected can be difficult. Visual inspection can over diagnose these injuries leading to unnecessary surgery. One would prefer to limit major pancreatic procedures to those patients with hemorrhagic shock or those without other options.

While endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) is the most accurate method for assessing PD integrity and extent of injury, its wide spread use is hindered due to limited resources, local expertise and difficulty performing the procedure itself in an emergent, operative setting[1,7]. ERCP can also be therapeutic as PD stenting can be performed at the time of diagnosis. Stenting a duct that is transected can be challenging but if successful, the duct may heal around the stent and limit the need for major pancreatic resection. In this case series, we present two cases treated at a major urban trauma center where PD injuries were diagnosed with intraoperative ERCP and treated with sphincterotomy and stenting.

Case 1: Multiple gunshot wounds (GSWs).

Case 2: Blunt abdominal trauma.

Case 1: A 27-year-old male presented with four GSWs to the chest and abdomen.

Case 2: A 16-year-old female initially presented to an outside hospital with severe upper quadrant abdominal pain following blunt abdominal trauma. She remained at the hospital for two days with an inability to tolerate per oral intake, nausea, and vomiting.

Both patients had no specific history of past illness.

No pertinent personal or family history of both patients.

Case 1: Upon arrival he was found to have penetrating GSWs to the left shoulder, left axilla, right flank, and subxiphoid areas.

Case 2: Upon arrival she was afebrile (37 ℃), normotensive (119/71 mmHg) but tachycardic (130 beats per min) with abdominal tenderness to palpation.

Case 1: Labs on admission were notable for a white blood cell (WBC) count 10.9 K/mcL, hemoglobin 12.5 g/dL, platelets 430 K/mcL, international normalized ratio 1, aspartate transaminase (AST) 315, alanine transaminase (ALT) 282, alkaline phosphatase (ALP) 72, total bilirubin 0.2, amylase 127 units/L, lipase 59 units/L and lactate 6.8 nmol/L. He was resuscitated and imaging was obtained.

Case 2: Labs were notable for a WBC 16.6 K/mcL, Hg 11 g/dL, AST 23, ALT 12, ALP 74, total bilirubin 2.3 mg/dL, lipase 1160 units/L and amylase 441 units/L.

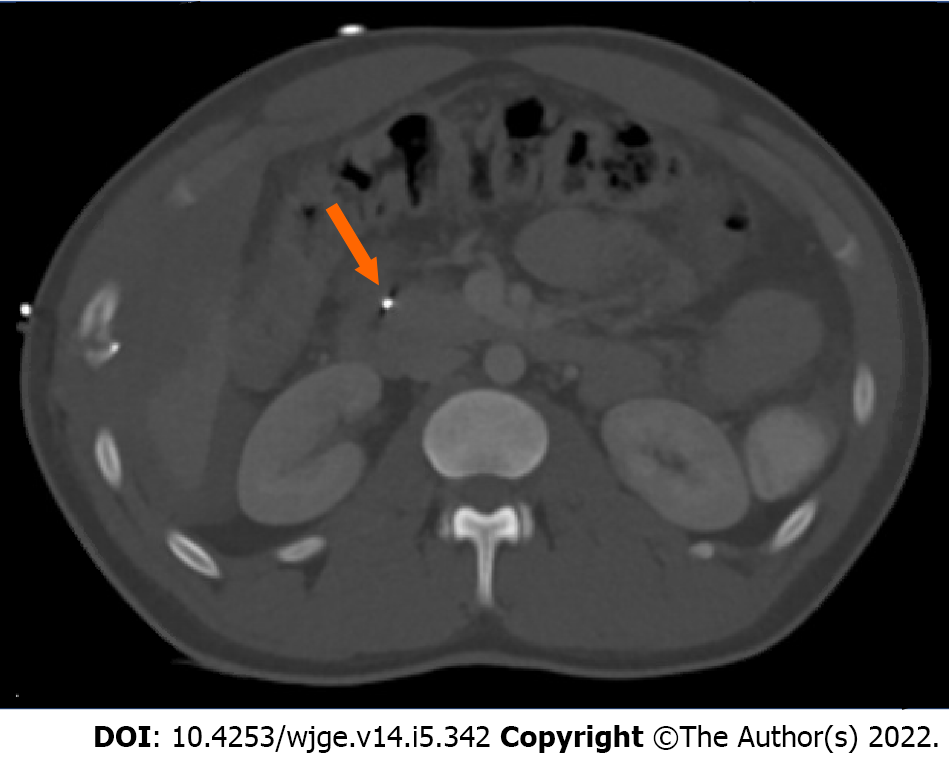

Case 1: Computed tomography angiography of the chest abdomen and pelvis revealed significant injuries, including but not limited to a left ventricle apex cardiac injury, laceration of liver lobe segments two and six, a pancreatic artery pseudoaneurysm (measuring 1.4 cm), and shrapnel wounds to the gallbladder, duodenum, pancreatic head, and hepatic flexure (Figure 1). There was no mention of pancreatic leak.

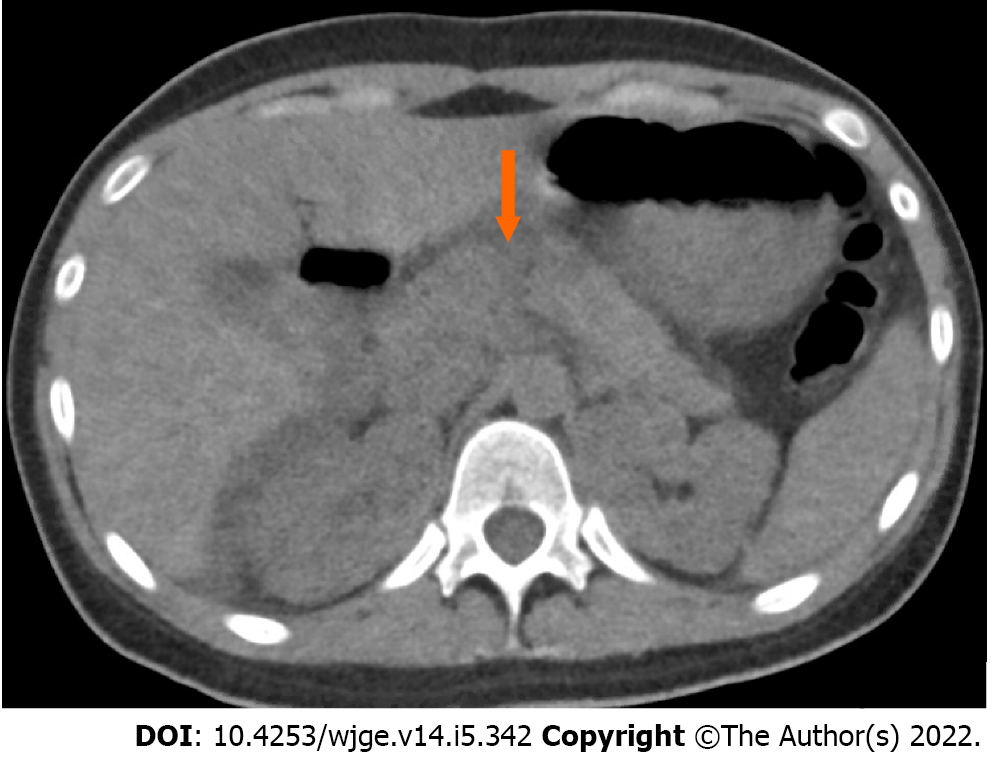

Case 2: A CT of the abdomen demonstrated a grade III pancreatic injury (thickness pancreatic transection involving the proximal tail and neck), large hemoperitoneum, and a 1 cm posterior splenic laceration for which she was transferred to our center for surgical care (Figure 2).

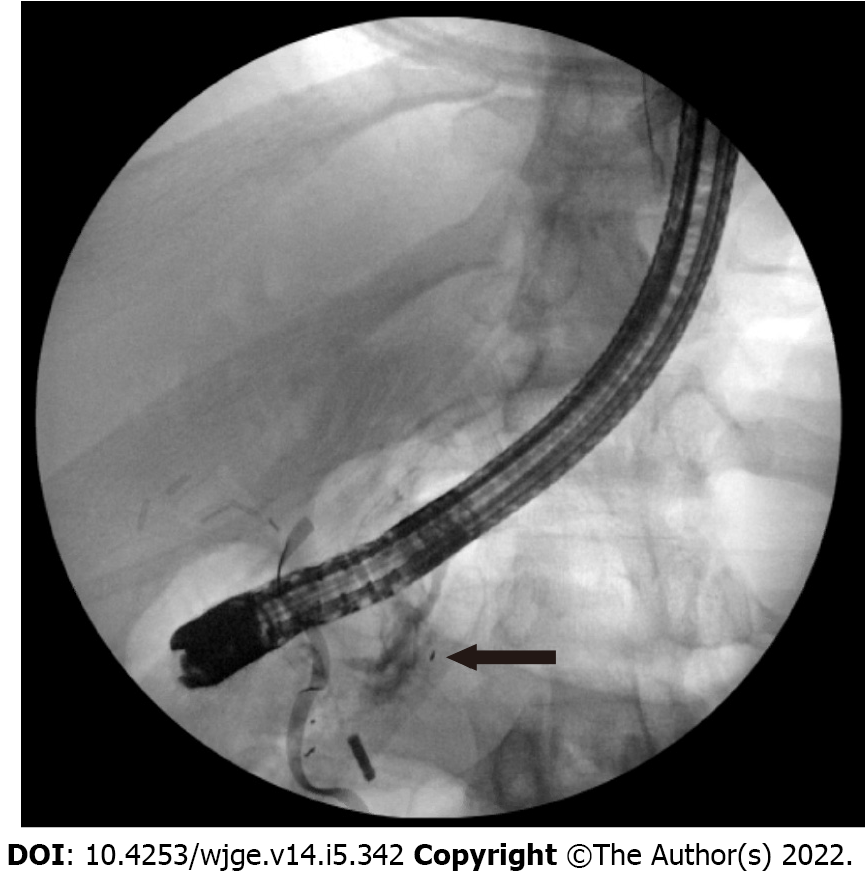

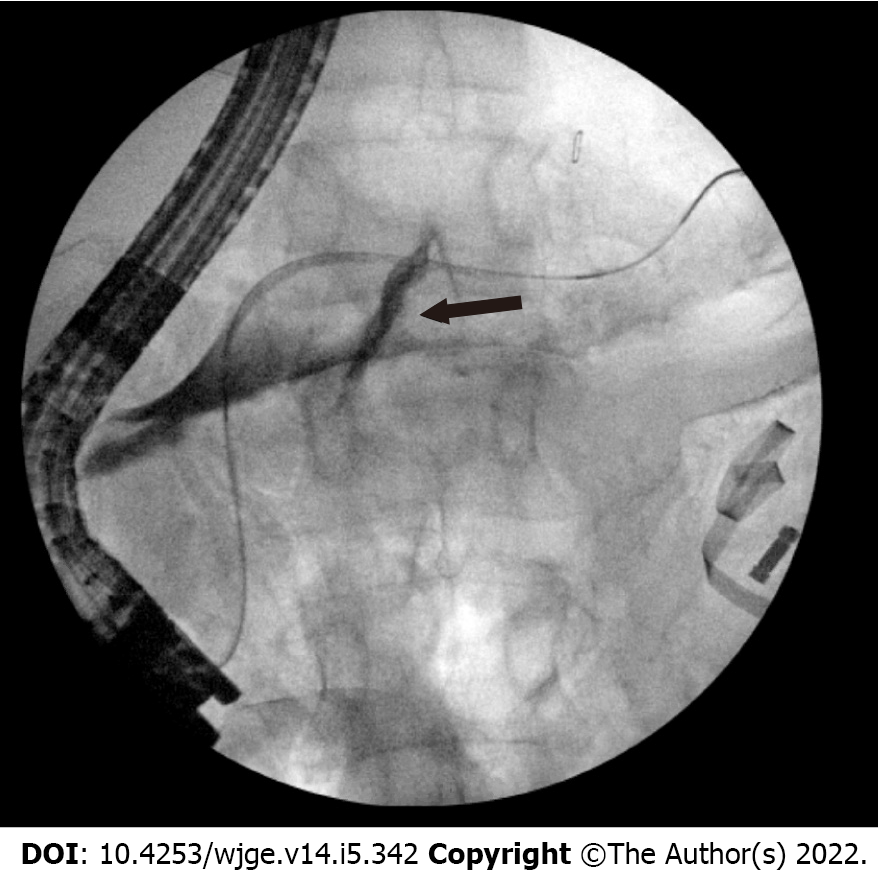

Case 1: He immediately went to the operating room (OR) for exploratory laparotomy where he underwent a non-anatomic bilateral liver resection, cholecystectomy, colon resection with end colostomy, gastric wedge resection, small bowel resection (20 cm) with anastomosis. He had a high-grade injury to his pancreatic head that would have required a Whipple to treat but it was not clear that he had a major PD injury. An intraoperative ERCP demonstrated a ventral PD leak in the head of the pancreas (Figure 3).

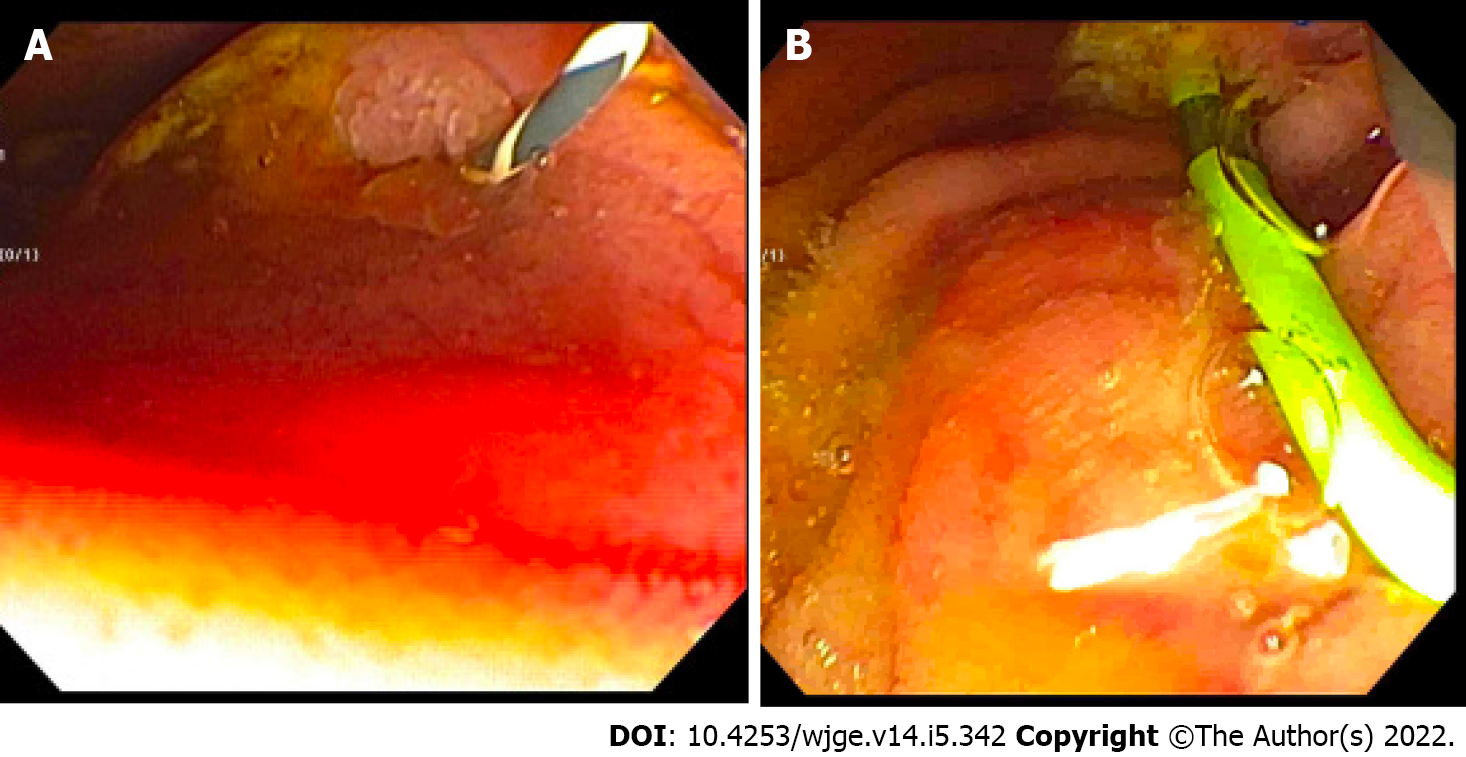

Case 2: She was sent directly to the OR, where an exploratory laparotomy revealed 500 mL of pancreatic ascites which was evacuated from the lesser sac and right upper quadrant. There was concern for PD disruption at proximal aspect of the pancreatic tail. An intraoperative ERCP demonstrated a PD leak in the body (Figure 4).

Both patients were diagnosed with PD leaks.

Following the diagnostic ERCP, the first patient, underwent a pancreatic sphincterotomy followed by plastic pancreatic stent placement (5 Fr by 10 cm) (Figure 5). The main pancreatic duct (MPD) was intact. There were no technical challenges or associated complications from the procedure itself. The time from admission to ERCP was 6.35 h (Table 1). A drain was placed, and output decreased from 600 cc/d to 300 cc/d over two days. The drain amylase level was > 24000 units/L. Six days after the ERCP, his labs improved with an AST 46, ALT 77, ALP 89, and a total bilirubin 0.3. His hospital course was protracted related to non-pancreatic complications. He developed an intra-abdominal abscess communicating with the right abdominal wall wound. A CT abdomen pelvis did not show signs of a leak. However, he underwent a repeat ERCP with PD stent exchange to a larger 7 Fr by 10 cm plastic stent 18 d later due to a persistent leak on pancreatogram, with no further issues.

| Patient | Age/sex | Etiology | Prior imaging | ERCP findings | Plastic biliary stent (Fr/cm) | Time from admission to ERCP (h) | Length of hospital stay |

| 1 | 27/male | Gunshot wound | Yes, CTA | Ventral PD leak in the head of the pancreas | 5/10 then upsized to 7/10 | 6.3 | 25 |

| 2 | 16/female | Blunt trauma | Yes, CT | Dorsal PD leak | 5/13 | 5.6 | 22 |

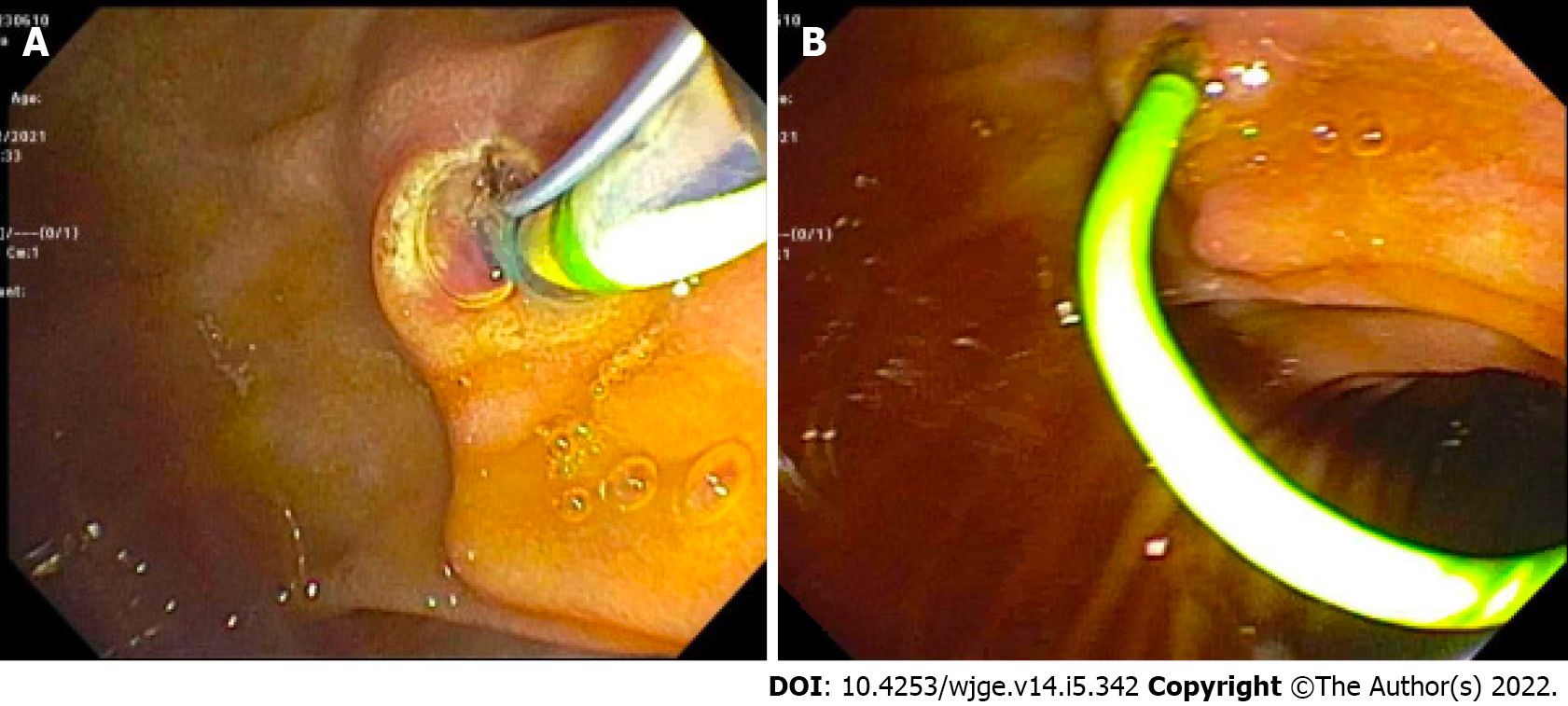

Similarly, in case 2, a 4 mm ventral sphincterotomy was performed followed by placement of a 5 Fr by 13 cm plastic stent into the dorsal pancreatic duct (Figures 6 and 7). There was no evidence of bile leakage. Her pancreas widely drained. The time from hospital admission to ERCP was 5.65 h. The procedure was technically successful with no adverse events. Her abdomen was left open. The next day, a MRCP confirmed placement of the pancreatic duct stent, which traversed the area of pancreatic transection with the tip of the stent residing in the tail of the pancreas. Two days after her initial surgery, she returned to the OR for abdominal re-exploration, pancreatic debridement, omentopexy, and primary closure.

Patient 1 was eventually discharged with a 25 d hospital length of stay. In the outpatient setting he underwent repeat ERCP with stent removal 84 d after discharge, with leak resolution and no further symptoms. The second patient’s hospital length of stay was 22 d, and she was discharged without any major ERCP or pancreatic related complications. She underwent a repeat ERCP with stent removal 59 d following its initial placement with resolution of ductal injury.

This series demonstrates the efficacy, safety, and feasibility of intraoperative ERCP as a diagnostic and therapeutic tool. In this case series the average time from admission to ERCP occurred within 5.95 h. Both patients also underwent successful stent removal without any post-ERCP complications and resolution in the PD injury.

Clinical manifestations and management of PD leaks are largely dependent on the leak’s size and location, where the integrity of the main duct influences prognosis[8]. In the setting of ductal injury, high pressure gradients cause pancreatic juices to flow outwards; as such, transpapillary stenting reduces the pressure gradient with preferential flow through the stent into the duodenum in order for the injury to properly heal. At our center, we always perform a sphincterotomy with stent placement instead of employing nasobiliary catheter, with well documented success in cases of hepatic trauma as well[9].

The role of intraoperative ERCP in the trauma setting is not yet well defined. In a study of 71 patients with pancreatic injury, 50 of whom underwent immediate laparotomy, there was a 14% complication and 20% mortality rate[4]. In that study, intraoperative ERCP was not used. Instead, intraoperative visual inspection was undertaken to investigate for ductal injury. Four patients deemed not to have a leak developed pancreatic leaks with abscess formation. ERCP should be considered in the setting of traumatic pancreatic injury with a questionable PD injury. Its high diagnostic accuracy cannot be matched by any combination of a CT abdomen, serum amylase or peritoneal lavage[10]. In a large PD trauma series, an abdominal CT missed the diagnoses of major PD injury in 40.7% (11/27) of patients[11]. Furthermore, in a prospective study of 14 patients with PD injury, those undergoing ERCP greater than 72 h following trauma had higher rates of pancreatic complications and longer hospital stays[12]. In our series, both patients underwent ERCP immediately with no ERCP related complications or delayed lengths of hospital stays. One could postulate that early intraoperative ERCP effectively contained the leak and contributed to these positive outcomes.

ERCP with early stenting has also proven to be an effective and safe option in pediatric cases[13,14]. Yet, there has been some concern regarding the development of strictures, though it’s unclear if such a complication occurs from the trauma itself or stent-induced changes[7]. In a small study analyzing long term outcomes for pancreatic stenting from blunt trauma the authors found that only 50% (3/6) of stents were successfully removed at 12, 19, and 39 mo[15]. Such complications were not seen in our patients, likely because the stents were removed significantly earlier with minimal stent exchanges.

Studies exploring pancreatic trauma have not detailed intraoperative timing, which may be an important aspect for reducing complications as well. In a study of 43 patients with major PD trauma, 15 underwent stenting as the first treatment modality with a median time from trauma to ERCP of 6 d[12]. Within this group, there were 17 related complications including pseudocyst formation (8), PD stricture (4), distal pancreatic atrophy from injury site (3), and pancreatic fistulas (2). They also reported two deaths, one of which was related to severe pancreatitis where the stent was removed 8 d after insertion. The other death was attributed to a patient with severe alcoholic liver cirrhosis–unrelated to the stent. In another study of 48 patients with pancreatic trauma (26 blunt and 22 penetrating), the median time from presentation to ERCP was 38 d and only seven patients had a stent inserted for a pancreatic fistula (7) and a MPD stricture (1), whereby all patients avoided surgery[16]. While variable complications have been reported, the heterogeneity of presentations at different centers must be considered. The studies mentioned above did not employ, early intraoperative ERCP.

The logistics of performing intraoperative ERCP can limit its use, especially in cases of poly-trauma. Wise use of this novel technique requires commitment and flexibility from the surgeons and gastroenterologists. In instances of trauma, PD injury, duodenal injury and papilla edema may also increase the difficulty of the procedure itself, thereby increasing the chances of complications such as post-ERCP pancreatitis[17]. In both of our cases, there were no immediate or long term complications from the ERCP. Patient 1 did require upsizing from 5 Fr to 7 Fr stent, which is commonly seen. ERCP may be underutilized due to operator comfortability, lack of awareness of the value of endoscopic treatment in this setting, and equipment availability in the OR. Our high-volume trauma center is unique and is equipped to handle these situations with quick and effective mobilization of resources including on call therapeutic endoscopy.

In conclusion, this case series emphasizes the utility of intraoperative ERCP in cases of severe pancreatic trauma. Further studies are needed to clarify the optimal timing and safety outcomes in this setting.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: United States

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Ding WW, China; Elshimi E, Egypt S-Editor: Zhang H L-Editor: A P-Editor: Zhang H

| 1. | Rogers SJ, Cello JP, Schecter WP. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography in patients with pancreatic trauma. J Trauma. 2010;68:538-544. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Ho VP, Patel NJ, Bokhari F, Madbak FG, Hambley JE, Yon JR, Robinson BR, Nagy K, Armen SB, Kingsley S, Gupta S, Starr FL, Moore HR 3rd, Oliphant UJ, Haut ER, Como JJ. Management of adult pancreatic injuries: A practice management guideline from the Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2017;82:185-199. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 107] [Article Influence: 13.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Ando Y, Okano K, Yasumatsu H, Okada T, Mizunuma K, Takada M, Kobayashi S, Suzuki K, Kitamura N, Oshima M, Suto H, Nobuyuki M, Suzuki Y. Current status and management of pancreatic trauma with main pancreatic duct injury: A multicenter nationwide survey in Japan. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2021;28:183-191. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Schellenberg M, Inaba K, Bardes JM, Cheng V, Matsushima K, Lam L, Benjamin E, Demetriades D. Detection of traumatic pancreatic duct disruption in the modern era. Am J Surg. 2018;216:299-303. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Phelan HA, Velmahos GC, Jurkovich GJ, Friese RS, Minei JP, Menaker JA, Philp A, Evans HL, Gunn ML, Eastman AL, Rowell SE, Allison CE, Barbosa RL, Norwood SH, Tabbara M, Dente CJ, Carrick MM, Wall MJ, Feeney J, O'Neill PJ, Srinivas G, Brown CV, Reifsnyder AC, Hassan MO, Albert S, Pascual JL, Strong M, Moore FO, Spain DA, Purtill MA, Edwards B, Strauss J, Durham RM, Duchesne JC, Greiffenstein P, Cothren CC. An evaluation of multidetector computed tomography in detecting pancreatic injury: results of a multicenter AAST study. J Trauma. 2009;66:641-6; discussion 646. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Fulcher AS, Turner MA, Yelon JA, McClain LC, Broderick T, Ivatury RR, Sugerman HJ. Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) in the assessment of pancreatic duct trauma and its sequelae: preliminary findings. J Trauma. 2000;48:1001-1007. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 98] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Bhasin DK, Rana SS, Rawal P. Endoscopic retrograde pancreatography in pancreatic trauma: need to break the mental barrier. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;24:720-728. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Larsen M, Kozarek R. Management of pancreatic ductal leaks and fistulae. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;29:1360-1370. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 95] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Anand RJ, Ferrada PA, Darwin PE, Bochicchio GV, Scalea TM. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography is an effective treatment for bile leak after severe liver trauma. J Trauma. 2011;71:480-485. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Barkin JS, Ferstenberg RM, Panullo W, Manten HD, Davis RC Jr. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography in pancreatic trauma. Gastrointest Endosc. 1988;34:102-105. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Kim HS, Lee DK, Kim IW, Baik SK, Kwon SO, Park JW, Cho NC, Rhoe BS. The role of endoscopic retrograde pancreatography in the treatment of traumatic pancreatic duct injury. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;54:49-55. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 110] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Kim S, Kim JW, Jung PY, Kwon HY, Shim H, Jang JY, Bae KS. Diagnostic and therapeutic role of endoscopic retrograde pancreatography in the management of traumatic pancreatic duct injury patients: Single center experience for 34 years. Int J Surg. 2017;42:152-157. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Halvorson L, Halsey K, Darwin P, Goldberg E. The safety and efficacy of therapeutic ERCP in the pediatric population performed by adult gastroenterologists. Dig Dis Sci. 2013;58:3611-3619. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Canty TG Sr, Weinman D. Treatment of pancreatic duct disruption in children by an endoscopically placed stent. J Pediatr Surg. 2001;36:345-348. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Lin BC, Liu NJ, Fang JF, Kao YC. Long-term results of endoscopic stent in the management of blunt major pancreatic duct injury. Surg Endosc. 2006;20:1551-1555. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Thomson DA, Krige JE, Thomson SR, Bornman PC. The role of endoscopic retrograde pancreatography in pancreatic trauma: a critical appraisal of 48 patients treated at a tertiary institution. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2014;76:1362-1366. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Cheng CL, Sherman S, Watkins JL, Barnett J, Freeman M, Geenen J, Ryan M, Parker H, Frakes JT, Fogel EL, Silverman WB, Dua KS, Aliperti G, Yakshe P, Uzer M, Jones W, Goff J, Lazzell-Pannell L, Rashdan A, Temkit M, Lehman GA. Risk factors for post-ERCP pancreatitis: a prospective multicenter study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:139-147. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 414] [Cited by in RCA: 434] [Article Influence: 22.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |