Published online May 16, 2022. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v14.i5.302

Peer-review started: November 4, 2021

First decision: November 29, 2021

Revised: December 30, 2021

Accepted: April 21, 2022

Article in press: April 21, 2022

Published online: May 16, 2022

Processing time: 192 Days and 22.1 Hours

Endoscopy is a complex procedure that requires advanced training and a highly skilled practitioner. The advances in the field of endoscopy have made it an invaluable diagnostic tool, but the procedure remains provider dependent. The quality of endoscopy may vary from provider to provider and, as a result, is not perfect. Consequently, 11.3% of upper gastrointestinal neoplasms are missed on the initial upper endoscopy and 2.1%-5.9% of colorectal polyps or cancers are missed on colonoscopy. Pathology is overlooked if endoscopic exam is not done carefully, bypassing proper visualization of the scope’s entry and exit points or, if exam is not taken to completion, not visualizing the most distal bowel segments. We hope to shed light on this issue, establish areas of weakness, and propose possible solutions and preventative measures.

Core Tip: Endoscopy has become a widely used diagnostic tool and plays an instrumental role in screening and surveillance of gastrointestinal pathology. Despite its wide acceptance, it remains provider dependents and, as a result, is not perfect. Both upper and lower endoscopy have weaknesses and shortcomings unless executed flawlessly. A high-quality endoscopy includes a complete examination of the bowel, including distal segments that are difficult to visualize, as well as scope’s entry and exit points. Better understanding of the shortcomings of endoscopy may help change training and improve physician awareness.

- Citation: Turshudzhyan A, Rezaizadeh H, Tadros M. Lessons learned: Preventable misses and near-misses of endoscopic procedures. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2022; 14(5): 302-310

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v14/i5/302.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v14.i5.302

Today, endoscopy is considered one of the best diagnostic tools for screening and surveillance of gastrointestinal pathology. Since the beginning of the 21st century, endoscopy use has risen by more than 50%[1]. With wider utilization of endoscopy, it has become more and more evident that the procedure quality is multifactorial and operator dependent[2]. Consequently, lesions may be missed depending on the level of provider training, procedural skills, and attentiveness to subtle pathology. This prompted development of several quality metrics to provide guidance for operators[3-7]. Despite proposed quality metrics, there is still a significant number of missed gastrointestinal cancers. A meta-analysis by Menon et al[8] suggested that 11.3% of upper gastrointestinal (UGI) neoplasms are overlooked on the initial upper endoscopy (EGD). Around 2.1%-5.9% of colorectal polyps or cancers are missed on colonoscopy[9]. The difference likely stems from the fact that endoscopic training has historically put emphasis on colorectal cancer prevention and screening, while there is usually less awareness around UGI neoplasms.

It should be noted that aside from neoplastic lesions, bleeding sources can be missed on endoscopy and only seen on repeat examination in patients with unexplained occult GI bleed or iron deficiency anemia with negative diagnostic work up[10]. Missed lesions on endoscopy are a common reason for malpractice lawsuits[11], which further emphasizes the importance of quality improvement. Some of the common reasons for why pathology is overlooked are a hastily performed endoscopy that bypasses proper visualization of the scope’s entry and exit points, not taking endoscopic exam to completion, and not visualizing more distal bowel segments.

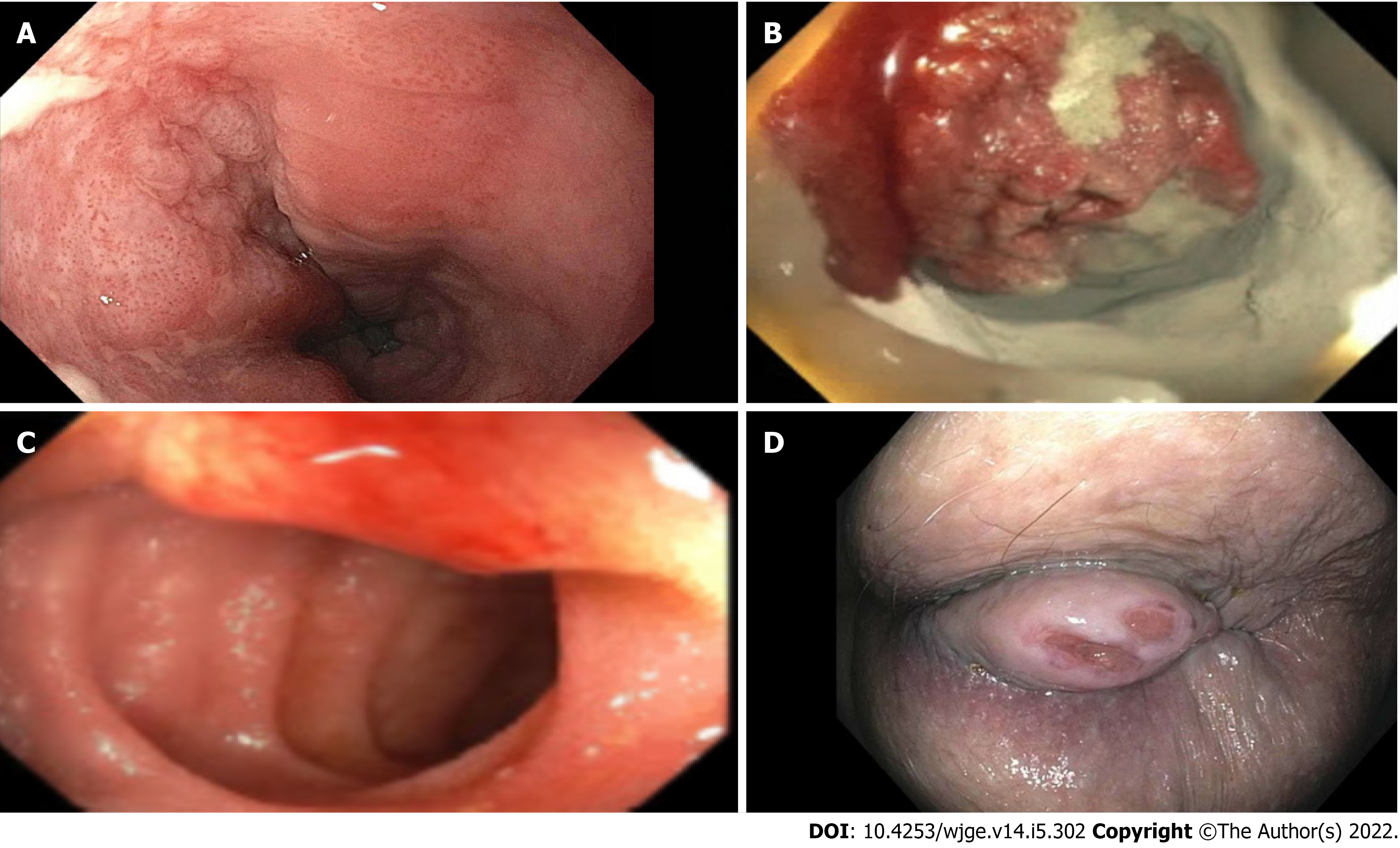

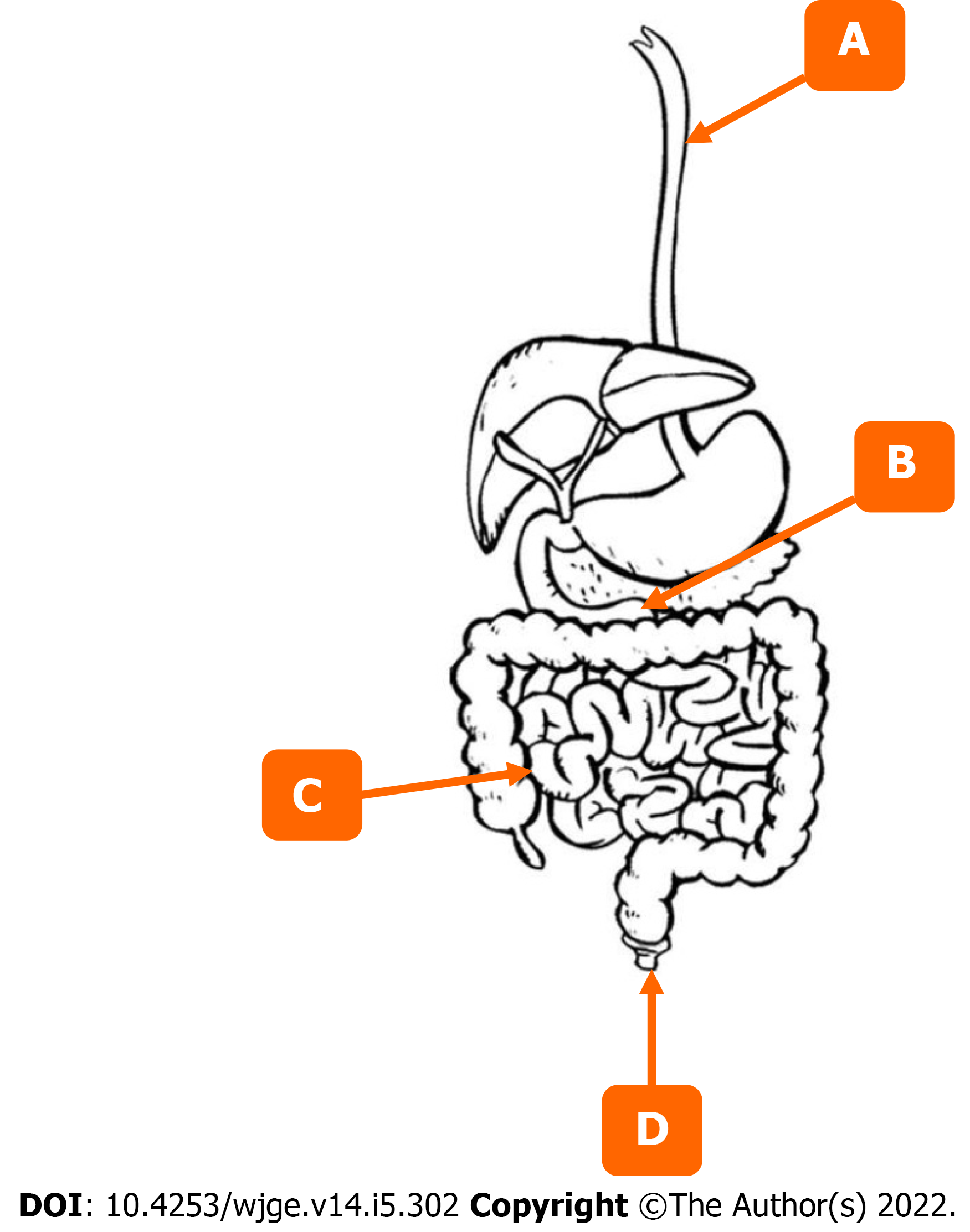

Using our personal experience with 4 patients who had lesions missed or near missed on endoscopy, we hope to expose some of the weaknesses and shortcomings of endoscopy. Our goal is to bring the attention of other gastroenterologists to these commonly missed areas that may go undetected.

The first patient was a 72-year-old male who presented with symptoms of dysphagia. The initial EGD was unrevealing. It was only after the second EGD that a flat squamous cell carcinoma was appreciated 2 cm below the upper esophageal sphincter (UES) (Figure 1A, Figure 2A). The lesion was missed on the initial scope insertion and was likely missed because of a rapid scope withdrawal.

The second patient was a 40-year-old female with iron deficiency anemia requiring multiple blood transfusions. The patient had undergone multiple upper and lower endoscopies and a capsule study, all of which were unrevealing. It was only after the 4th portion of the duodenum was examined that a malignant gastrointestinal stromal tumor was identified, diagnosed, and resected (Figures 1B and 2B).

The third patient was a 50-year-old female who presented with ongoing diarrhea. Stool studies revealed cryptosporidium. Fortunately, the patient’s colonoscopy included examination of the terminal ileum and was able to detect a small submucosal carcinoid tumor (Figures 1C and 2C). It was successfully resected with metastatic disease noted in only one lymph node.

Our last patient was a 68-year-old with a history of cirrhosis and recurrent bright red blood per rectum. She had 2 colonoscopies done to find the bleeding source, both were unrevealing. It was months later that the patient had a 2 cm anal growth examined and diagnosed on careful retroflexion. The anal lesion was then seen on a reinspection of the anal area. (Figures 1D and 2D).

Increasing awareness of the bowel segments at risk for being missed on endoscopy is important. Similarly, it is important to incorporate technical maneuvers that could help identify these challenging lesions into fellowship training and post-graduate courses to help practicing endoscopists (Tables 1 and 2)[10]. Lastly, following the most recent endoscopy quality metrics will help improve the detection of challenging lesions.

| Bowel segment | Lesions missed | Intervention to improve lesion detection |

| Anorectum | Anal/rectal cancers | Careful anorectal exam before and on scope insertion with retroflexion |

| Anal fissures | ||

| Recto-cutaneous fistulas | ||

| Anal warts | ||

| Colon | Lesions in colonic folds (particularly sigmoid) | Careful exam between the folds of the colon, especially in sigmoid segment, consider using a cap |

| Excellent, good, or adequate bowel preparation, supported by photography | ||

| Right colon | Second look | |

| Retroflex in right colon | ||

| Cecum (especially behind IC valve) | Document examination | |

| Examine behind the ileocecal valve | ||

| Cecal intubation rate | ||

| Terminal ileum | Lesions in ileum | Intubate in the terminal ileum |

| Esophagus | Below UES lesions, i.e., squamous cell carcinoma | Careful examination of upper esophagus, slow scope withdrawal |

| Distal esophagus, collapsed varices in volume depleted patient | Careful examination of distal esophagus and awareness of patient’s volume status | |

| Subtle lesions of Barrett segment | Adequate time for examination of the segment | |

| Stomach | Cameron lesions, gastro-esophageal junction (especially challenging to detect/examine with large hiatal hernias) | Careful examination of gastro-esophageal junction and diaphragmatic hiatus with retroflexion of the scope |

| Arteriovenous malformation, Dieulafoy’s lesions | Careful inspection between the gastric folds using a cap | |

| Small bowel | Duodenal bulb | Examine all 4 walls of the duodenal bulb and |

| Duodenal sweep | May need to use of a side view scope | |

| 3rd and 4th part of the duodenum | Advance scope by reducing the loop into 3rd and 4th parts of duodenum |

| Colonoscopy | EGD |

| High quality bowel preparation (excellent, good, or adequate), documented with photos | At least 1 min of inspection per centimeter of circumferential segment of Barrett’s esophagus |

| Digital rectal examination prior to colonoscopy with results documented | NDR record should be considered |

| When evaluating for gastric intestinal metaplasia, 5 or more biopsies need to be taken | |

| Cecal intubation performed, landmarks noted in documentation and photos recorded | Overall, EGD evaluation for gastric intestinal metaplasia has to last 7 min or more |

| Withdrawal time is 6 min or more | |

| Retroflexion, if performed, is thoroughly documented (with photographs) | |

| Endoscopists ADR exceeds recommended thresholds. Physician participates in quality-improvement and continues to measure individual ADR |

A complete colonoscopy should include a thorough exam of the endoscope’s entry point (anal canal), all segments of the colon, and, if possible, the distal ileum. We are going to discuss distal to proximal bowel segments as visualized on colonoscopy and use it as a framework to go over commonly missed lesions for each segment along with maneuvers and techniques that can help detect them.

Anorectum: Some of the commonly missed lesions in anorectum are anal and rectal cancer, anal fissures, recto cutaneous fistulas, anal warts (Table 1)[10]. This is likely because of the scopes entry point being overlooked or not property visualized at the beginning of the procedure. The importance of anal examination by a skilled endoscopist if further emphasized by the fact that anorectal lesions can have a non-specific presentation and may go undiagnosed by patient’s primary care physician. Chiu et al[12] found that only 54% of patients have a rectal examination by their primary care provider when they present with a non-specific anal complaint. Another study indicated that only 23% of patients presenting with anal complaint were diagnosed correctly by their primary care provider; the remaining patients were erroneously diagnosed with hemorrhoids[13]. As a result, this leads to delay in diagnosis and management of anal and rectal cancers. As proposed by quality metrics, digital rectal exam needs to be performed and thoroughly documented prior to colonoscopy (Table 2)[11]. Another maneuver that could be used to enhance detection of challenging lesions in anorectum is retroflexion. It allows for a better visualization of distal rectum and distal anus (Table 1)[14]. Retroflexion needs to be photographed and documented[11].

Colon: Some of the commonly missed lesion of colonic segment include lesions found inside the colonic folds (especially in sigmoid colon), right-sided colon, cecum [especially behind the ileocecal (IC) valve], and distal ileum (Table 1). There are a few techniques that can be implemented to facilitate detection of these challenging lesions (Table 1). Endoscopists should do a thorough examination between the haustral folds to avoid missing even large polyps that can hide inside the folds. Cap-assisted colonoscopy is another acceptable option as it involves a transparent attachment at the end of the scope that can improve adenoma detection rate (ADR) by flattening of the haustral folds and improving visualization of mucosa, especially on scope withdrawal[15].

Second look examination of the right side of the colon can help reduce the rate of cecal lesions missed[16]. Retroflexion in the right colon is another maneuver that can enhance visualization of right-sided lesions and improve ADR[14,16]. It entails bending of the scope in a U-turn such that viewing lens is facing backwards[14].

Cecum intubation is a very important skill and a quality measure that can enhance visualization of the cecum and identify lesions that are oftentimes missed. Additionally, endoscopists should pay particular attention to the mucosa behind the IC valve. Documentation of cecal landmarks is crucial.

All maneuvers discussed need to be thoroughly photographed and documented in the procedure description per the colonoscopy quality metrics (Table 2). Quality metrics further require bowel preparation to be excellent, good, or adequate and supported by photography and withdrawal time should be noted in documentation and exceed 6 minutes[11]. It is also encouraged that practicing endoscopist’s adenoma detection rate (ADR) exceeds recommended thresholds. Physicians should routinely measure their ADR and participate in quality improvement programs[11].

The optimal withdrawal time for colonoscopy remains an important topic. A 6-minute withdrawal time was accepted, but a recent meta-analysis by Bhurwal et al[17] of 69551 patients compared withdrawal time of 6 vs 9 min in its ability to detect adenomas. They found that odds ratio for ADR was significantly higher at 1.54 for colonoscopies with withdrawal time of 9 min or more[17].

Terminal ileum: Lesions can be missed in terminal ileum as many colonoscopies do not investigate this bowel segment. It is important to note that the ileum is the most common site for development of carcinoid tumors (57%) and that even primary ileal tumors are missed on computer tomography (CT) scans in 64% of cases[18-20].This emphasizes the importance of a thorough and complete endoscopic exam that may detect primary ileal tumors early and allow for timely intervention[20]. Endoscopists should try to intubate the terminal ileum whenever feasible.

A complete EGD should entail a thorough exam of the esophagus, including the UES, point of entry into the stomach, other poorly visualized areas of the stomach, along with all segments of the duodenum. We are going to discuss distal to proximal bowel segments as visualized on EGD and use it as a framework to go over commonly missed lesions for each segment along with maneuvers and techniques to help detect them.

Esophagus: Some of the most commonly missed esophageal lesions are immediately below the UES and lesions in the distal esophagus (such as collapsed varices in a volume depleted patient or subtle changes of Barrett’s segment) (Table 1)[10]. Some possible interventions to facilitate detection of challenging lesions are careful examination of the full length esophagus paying particular attention to upper and lower most segments, being aware of patient’s volume status, and allotting adequate time for examination of the segment (Table 1). Quality metrics for Barrett’s segment inspection time call for 1 minute inspection time per cm of circumferential length[21]. Longer inspection time results in a more careful visualization of the mucosa and subsequently increase chances of detecting pathology[21]. Another quality metric that is being proposed when examining esophagus is neoplasia detection rate (NDR)[22]. Like ADR for colonoscopy, it is important to keep track of NDR for EGD when examining for Barrett’s segment, because it reflects the quality of inspection[22].

Stomach: Some of the common gastric lesions missed on EGD are Cameron lesions, lesions around gastro-esophageal (GE) junction (especially with large hiatal hernias), arteriovenous malformations, Dieulafoy lesions (Table 1). Some interventions that can be done are careful inspection of GE and diaphragmatic hiatus with retroflexion of the scope, inspection between gastric folds using the previously discussed cap-assisted endoscopy (Table 1)[23]. One of the EGD quality metrics that is important to remember is adequate number of gastric biopsies, which should be greater or equal to 5[24]. Timing is another important quality metric. Examination time during EGD when looking for intestinal metaplasia should be longer than 7 min, because longer inspection implies a more careful exam and results in a higher rate of neoplasia detection[25]. Park et al[25] observed that slow endoscopists (defined as withdrawal time of more than 3 min) were better at detecting neoplastic lesions (0.28%) compared to fast endoscopists (0.20%). As a result, they proposed that examination time could be a surrogate measure for the procedure quality[25]. Another study identified that endoscopist who takes more than 7 min to complete exams is more likely to detect a high-risk gastric lesion when compared to a fast endoscopist[26]. Given heterogeneity of data between the two studies, it is difficult to draw conclusions regarding the optimal examination time. This is further complicated by the fact that longer endoscopic times are associated with cardiac arrythmias, esophageal tears, aspiration, and bacterial translocation[27].

Incidence of gastric pathology varies in different countries. There is higher prevalence of gastric cancer in Eastern countries. Consequently, this led to increased awareness of gastric lesions and a more robust screening protocols in countries like Japan[28]. In Japan, it is recommended to undergo annual upper endoscopy for anybody over the age 40. As a result, there are more early-stage gastric lesions (53%) identified when compared to United States (27%)[29,30]. This shows that increased awareness and adequate training can improve subtle lesion detection.

Some of the commonly missed segments of the small bowel are duodenal bulb, duodenal sweep, and 3rd and 4th parts of the duodenum (Table 1). Some of the maneuvers that can help detect these challenging lesions are careful examination of all 4 walls of the duodenal bulb, use of a side view scope for the duodenal sweep, advancement of the scope by reducing the loop into the 3rd and 4th parts of duodenum (Table 1). Many upper endoscopies do not go past the 2nd part of the duodenum. Lesions in more distal segments of the duodenum (3rd and 4th) are usually more challenging to visualize and require an extra-log fiber optic scope and a trained endoscopist[31]. Interestingly, 60% of benign duodenal lesions and 50% of malignant duodenal lesions are only diagnosed on autopsy and missed on the endoscopic exam[32].

As we learn more about common pitfalls and shortcomings of endoscopy, training fellows to recognize them becomes the next key step. It is important to standardize best practices and shed light on the areas commonly missed in colonoscopy training[33]. One of the studies even suggested that pre-fellowship exposure to best practices of endoscopy, can improve the learning period and procedural skill of fellows[34].

Endoscopy continues to be an operator dependent procedure. As such, it presents a growing opportunity for development of machine learning technology and computer algorithms to assist endoscopists with lesion detection. Artificial intelligent (AI) has a promise to improve accuracy of endoscopic procedures, reduce inter-operator variability, and compensate for human error and factors contributing to it such as fatigue or limited experience[35]. Thus far, computer-aided detection algorithms of AI have been trained to detect lesions both macroscopically and by optical biopsy/ microscopically[36]. Recent studies demonstrated that AI performed better than endoscopists in esophageal cancer and neoplasm detection in pooled sensitivity 94% vs 82%, respectively[37]. The specificity of AI-based endoscopy had specificity of 85% for esophageal cancer and neoplasms[37]. AI-based endoscopy provided a 26.5% increase in sensitivity for detection of early gastric cancer when compared to endoscopists (sensitivity of 95%)[38]. The specificity of AI-based endoscopy had specificity of 87.3% for early gastric cancer[38]. AI algorithms have also been targeted towards colorectal cancer detection. Recent reports suggest that AI-assisted colonoscopy has sensitivity of 94% [39,40]. While some reports suggest that AI may not show significant improvement in larger polyp detection rate (38.8% vs 26.2%), AI-based colonoscopy showed significant improvement in detection of small and flat polyps that are easily missed (76.0% vs 68.8% and 5.9% vs 3.3%, respectively)[41].

Endoscopy has developed into a sophisticated diagnostic tool that provides great accuracy in lesion detection, but it is not perfect and remains operator dependent. The cases we presented expose weaknesses and shortcomings of endoscopic examination for both the upper and lower gastrointestinal tract, providing an opportunity for improvement. Commonly missed areas and the reason for why they were missed need to be communicated to currently practicing gastroenterologists. Additionally, educating fellows during their training on the possible shortcomings and weaknesses of endoscopy may help improve the quality of procedures in the future.

Provenance and peer review: Invited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: United States

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Hosoe N, Japan; Roma M, India S-Editor: Xing YX L-Editor: A P-Editor: Xing YX

| 1. | Peery AF, Dellon ES, Lund J, Crockett SD, McGowan CE, Bulsiewicz WJ, Gangarosa LM, Thiny MT, Stizenberg K, Morgan DR, Ringel Y, Kim HP, DiBonaventura MD, Carroll CF, Allen JK, Cook SF, Sandler RS, Kappelman MD, Shaheen NJ. Burden of gastrointestinal disease in the United States: 2012 update. Gastroenterology. 2012;143:1179-1187.e3. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1355] [Cited by in RCA: 1467] [Article Influence: 112.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Januszewicz W, Kaminski MF. Quality indicators in diagnostic upper gastrointestinal endoscopy. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2020;13:1756284820916693. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Beg S, Ragunath K, Wyman A, Banks M, Trudgill N, Pritchard DM, Riley S, Anderson J, Griffiths H, Bhandari P, Kaye P, Veitch A. Quality standards in upper gastrointestinal endoscopy: a position statement of the British Society of Gastroenterology (BSG) and Association of Upper Gastrointestinal Surgeons of Great Britain and Ireland (AUGIS). Gut. 2017;66:1886-1899. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 243] [Cited by in RCA: 224] [Article Influence: 28.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Bisschops R, Areia M, Coron E, Dobru D, Kaskas B, Kuvaev R, Pech O, Ragunath K, Weusten B, Familiari P, Domagk D, Valori R, Kaminski MF, Spada C, Bretthauer M, Bennett C, Senore C, Dinis-Ribeiro M, Rutter MD. Performance measures for upper gastrointestinal endoscopy: a European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Quality Improvement Initiative. Endoscopy. 2016;48:843-864. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 252] [Cited by in RCA: 241] [Article Influence: 26.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Park WG, Shaheen NJ, Cohen J, Pike IM, Adler DG, Inadomi JM, Laine LA, Lieb JG 2nd, Rizk MK, Sawhney MS, Wani S. Quality indicators for EGD. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110:60-71. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | ASGE Endoscopy Unit Quality Indicator Taskforce, Day LW, Cohen J, Greenwald D, Petersen BT, Schlossberg NS, Vicari JJ, Calderwood AH, Chapman FJ, Cohen LB, Eisen G, Gerstenberger PD, Hambrick RD 3rd, Inadomi JM, MacIntosh D, Sewell JL, Valori R. Quality indicators for gastrointestinal endoscopy units. VideoGIE. 2017;2:119-140. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Rex DK, Schoenfeld PS, Cohen J, Pike IM, Adler DG, Fennerty MB, Lieb JG 2nd, Park WG, Rizk MK, Sawhney MS, Shaheen NJ, Wani S, Weinberg DS. Quality indicators for colonoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;81:31-53. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 649] [Cited by in RCA: 836] [Article Influence: 83.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Menon S, Trudgill N. How commonly is upper gastrointestinal cancer missed at endoscopy? Endosc Int Open. 2014;2:E46-E50. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 176] [Cited by in RCA: 230] [Article Influence: 20.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Bressler B, Paszat LF, Chen Z, Rothwell DM, Vinden C, Rabeneck L. Rates of new or missed colorectal cancers after colonoscopy and their risk factors: a population-based analysis. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:96-102. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 442] [Cited by in RCA: 449] [Article Influence: 24.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Tadros M, Wu GY. Management of occult gi bleeding a clinical guide. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2021. |

| 11. | Rex DK. Avoiding and defending malpractice suits for postcolonoscopy cancer: advice from an expert witness. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;11:768-773. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Chiu S, Joseph K, Ghosh S, Cornand RM, Schiller D. Reasons for delays in diagnosis of anal cancer and the effect on patient satisfaction. Can Fam Physician. 2015;61:e509-e516. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Edwards AT, Morus LC, Foster ME, Griffith GH. Anal cancer: the case for earlier diagnosis. J R Soc Med. 1991;84:395-397. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Rex DK, Vemulapalli KC. Retroflexion in colonoscopy: why? Gastroenterology. 2013;144:882-883. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Pohl H, Bensen SP, Toor A, Gordon SR, Levy LC, Berk B, Anderson PB, Anderson JC, Rothstein RI, MacKenzie TA, Robertson DJ. Cap-assisted colonoscopy and detection of Adenomatous Polyps (CAP) study: a randomized trial. Endoscopy. 2015;47:891-897. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Ai X, Qiao W, Han Z, Tan W, Bai Y, Liu S, Zhi F. Results of a second examination of the right side of the colon in screening and surveillance colonoscopy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;30:181-186. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Bhurwal A, Rattan P, Sarkar A, Patel A, Haroon S, Gjeorgjievski M, Bansal V, Mutneja H. A comparison of 9-min colonoscopy withdrawal time and 6-min colonoscopy withdrawal time: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;36:3260-3267. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Baxi AJ, Chintapalli K, Katkar A, Restrepo CS, Betancourt SL, Sunnapwar A. Multimodality Imaging Findings in Carcinoid Tumors: A Head-to-Toe Spectrum. Radiographics. 2017;37:516-536. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Modlin IM, Lye KD, Kidd M. A 5-decade analysis of 13,715 carcinoid tumors. Cancer. 2003;97:934-959. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1848] [Cited by in RCA: 1852] [Article Influence: 84.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 20. | Gupta A, Lubner MG, Wertz RM, Foley E, Loeffler A, Pickhardt PJ. CT detection of primary and metastatic ileal carcinoid tumor: rates of missed findings and associated delay in clinical diagnosis. Abdom Radiol (NY). 2019;44:2721-2728. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Gupta N, Gaddam S, Wani SB, Bansal A, Rastogi A, Sharma P. Longer inspection time is associated with increased detection of high-grade dysplasia and esophageal adenocarcinoma in Barrett's esophagus. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;76:531-538. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 146] [Cited by in RCA: 152] [Article Influence: 11.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Parasa S, Desai M, Vittal A, Chandrasekar VT, Pervez A, Kennedy KF, Gupta N, Shaheen NJ, Sharma P. Estimating neoplasia detection rate (NDR) in patients with Barrett's oesophagus based on index endoscopy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gut. 2019;68:2122-2128. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Karaca C, Daglilar ES, Soyer OM, Gulluoglu M, Brugge WR. Endoscopic submucosal resection of gastric subepithelial lesions smaller than 20 mm: a comparison of saline solution-assisted snare and cap band mucosectomy techniques. Gastrointest Endosc. 2017;85:956-962. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Dinis-Ribeiro M, Areia M, de Vries AC, Marcos-Pinto R, Monteiro-Soares M, O'Connor A, Pereira C, Pimentel-Nunes P, Correia R, Ensari A, Dumonceau JM, Machado JC, Macedo G, Malfertheiner P, Matysiak-Budnik T, Megraud F, Miki K, O'Morain C, Peek RM, Ponchon T, Ristimaki A, Rembacken B, Carneiro F, Kuipers EJ; European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy; European Helicobacter Study Group; European Society of Pathology; Sociedade Portuguesa de Endoscopia Digestiva. Management of precancerous conditions and lesions in the stomach (MAPS): guideline from the European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE), European Helicobacter Study Group (EHSG), European Society of Pathology (ESP), and the Sociedade Portuguesa de Endoscopia Digestiva (SPED). Endoscopy. 2012;44:74-94. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 442] [Cited by in RCA: 489] [Article Influence: 37.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Park JM, Huo SM, Lee HH, Lee BI, Song HJ, Choi MG. Longer Observation Time Increases Proportion of Neoplasms Detected by Esophagogastroduodenoscopy. Gastroenterology. 2017;153:460-469.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 11.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Teh JL, Tan JR, Lau LJ, Saxena N, Salim A, Tay A, Shabbir A, Chung S, Hartman M, So JB. Longer examination time improves detection of gastric cancer during diagnostic upper gastrointestinal endoscopy. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13:480-487.e2. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 97] [Cited by in RCA: 142] [Article Influence: 14.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Kavic SM, Basson MD. Complications of endoscopy. Am J Surg. 2001;181:319-332. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 142] [Cited by in RCA: 115] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 28. | Hanazaki K, Sodeyama H, Wakabayashi M, Miyazawa M, Yokoyama S, Sode Y, Kawamura N, Miyazaki T, Ohtsuka M. Surgical treatment of gastric cancer detected by mass screening. Hepatogastroenterology. 1997;44:1126-1132. [PubMed] |

| 29. | Theuer CP. Asian gastric cancer patients at a southern California comprehensive cancer center are diagnosed with less advanced disease and have superior stage-stratified survival. Am Surg. 2000;66:821-826. [PubMed] |

| 30. | Theuer CP, Kurosaki T, Ziogas A, Butler J, Anton-Culver H. Asian patients with gastric carcinoma in the United States exhibit unique clinical features and superior overall and cancer specific survival rates. Cancer. 2000;89:1883-1892. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Markogiannakis H, Theodorou D, Toutouzas KG, Gloustianou G, Katsaragakis S, Bramis I. Adenocarcinoma of the third and fourth portion of the duodenum: a case report and review of the literature. Cases J. 2008;1:98. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 32. | Kaminski N, Shaham D, Eliakim R. Primary tumours of the duodenum. Postgrad Med J. 1993;69:136-138. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Kumar NL, Smith BN, Lee LS, Sewell JL. Best Practices in Teaching Endoscopy Based on a Delphi Survey of Gastroenterology Program Directors and Experts in Endoscopy Education. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;18:574-579.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Kim DH, Park SJ, Cheon JH, Kim TI, Kim WH, Hong SP. Does a Pre-Training Program Influence Colonoscopy Proficiency during Fellowship? PLoS One. 2016;11:e0164360. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | El Hajjar A, Rey JF. Artificial intelligence in gastrointestinal endoscopy: general overview. Chin Med J (Engl). 2020;133:326-334. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 13.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Li H, Hou X, Lin R, Fan M, Pang S, Jiang L, Liu Q, Fu L. Advanced endoscopic methods in gastrointestinal diseases: a systematic review. Quant Imaging Med Surg. 2019;9:905-920. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Zhang SM, Wang YJ, Zhang ST. Accuracy of artificial intelligence-assisted detection of esophageal cancer and neoplasms on endoscopic images: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Dig Dis. 2021;22:318-328. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Ikenoyama Y, Hirasawa T, Ishioka M, Namikawa K, Yoshimizu S, Horiuchi Y, Ishiyama A, Yoshio T, Tsuchida T, Takeuchi Y, Shichijo S, Katayama N, Fujisaki J, Tada T. Detecting early gastric cancer: Comparison between the diagnostic ability of convolutional neural networks and endoscopists. Dig Endosc. 2021;33:141-150. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 129] [Cited by in RCA: 104] [Article Influence: 26.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Kominami Y, Yoshida S, Tanaka S, Sanomura Y, Hirakawa T, Raytchev B, Tamaki T, Koide T, Kaneda K, Chayama K. Computer-aided diagnosis of colorectal polyp histology by using a real-time image recognition system and narrow-band imaging magnifying colonoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2016;83:643-649. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 157] [Cited by in RCA: 160] [Article Influence: 17.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Byrne MF, Chapados N, Soudan F, Oertel C, Linares Pérez M, Kelly R, Iqbal N, Chandelier F, Rex DK. Real-time differentiation of adenomatous and hyperplastic diminutive colorectal polyps during analysis of unaltered videos of standard colonoscopy using a deep learning model. Gut. 2019;68:94-100. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 363] [Cited by in RCA: 412] [Article Influence: 68.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Xu L, He X, Zhou J, Zhang J, Mao X, Ye G, Chen Q, Xu F, Sang J, Wang J, Ding Y, Li Y, Yu C. Artificial intelligence-assisted colonoscopy: A prospective, multicenter, randomized controlled trial of polyp detection. Cancer Med. 2021;10:7184-7193. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |