Published online Sep 16, 2021. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v13.i9.371

Peer-review started: February 13, 2021

First decision: March 28, 2021

Revised: April 20, 2021

Accepted: August 9, 2021

Article in press: August 9, 2021

Published online: September 16, 2021

Processing time: 208 Days and 17.8 Hours

Symptomatic biliary and gallbladder disorders are common in adults with cystic fibrosis (CF) and the prevalence may rise with increasing CF transmembrane conductance regulator modulator use. Cholecystectomy may be considered, but the outcomes of cholecystectomy are not well described among modern patients with CF.

To determine the risk profile of inpatient cholecystectomy in patients with CF.

The Nationwide Inpatient Sample was queried from 2002 until 2014 to investigate outcomes of cholecystectomy among hospitalized adults with CF compared to controls without CF. A propensity weighted sample was selected that closely matched patient demographics, patient’s individual comorbidities, and hospital characteristics. The propensity weighted sample was used to compare outcomes among patients who underwent laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Hospital outcomes of open and laparoscopic cholecystectomy were compared among adults with CF.

A total of 1239 inpatient cholecystectomies were performed in patients with CF, of which 78.6% were performed laparoscopically. Mortality was < 0.81%, similar to those without CF (P = 0.719). In the propensity weighted analysis of laparoscopic cholecystectomy, there was no difference in mortality, or pulmonary or surgical complications between patients with CF and controls. After adjusting for significant covariates among patients with CF, open cholecystectomy was independently associated with a 4.8 d longer length of stay (P = 0.018) and an $18449 increase in hospital costs (P = 0.005) compared to laparoscopic chole

Patients with CF have a very low mortality after cholecystectomy that is similar to the general population. Among patients with CF, laparoscopic approach reduces resource utilization and minimizes post-operative complications.

Core Tip: Cholecystectomy has been considered to be a high-risk intervention in adults with cystic fibrosis (CF). Our study used a sample of adults with closely matched baseline characteristics to compare hospital outcomes among patients with and without CF. There was no difference in mortality or pulmonary or surgical complications between adults with and without CF. Patients with CF who underwent an open cholecystectomy had a longer length of stay than those who underwent a laparoscopic cholecystectomy. This study suggests that cholecystectomy is safe in selected adults with CF and that a laparoscopic approach should be preferred.

- Citation: Ramsey ML, Sobotka LA, Krishna SG, Hinton A, Kirkby SE, Li SS, Meara MP, Conwell DL, Stanich PP. Outcomes of inpatient cholecystectomy among adults with cystic fibrosis in the United States. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2021; 13(9): 371-381

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v13/i9/371.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v13.i9.371

Cystic fibrosis (CF) is a multisystem disease resulting from defects in the CF tran

Biliary disorders are thought to be common in CF due to the high expression of the CFTR gene in the gallbladder and biliary tree[4]. The mechanism of gallstone formation in CF is incompletely understood, but is likely the result of biliary stasis due to gallbladder dysmotility and prolonged transit through the bile ducts[4,5]. Cholelithiasis is reported in 20%-30% of patients with CF, and symptomatic biliary colic is experienced by 4% to 40% of subjects in retrospective studies[6-8]. One case series suggested that the incidence of cholelithiasis increases with age, from 0.1% in those less than 5 years of age, to nearly 10% in those aged 30-40[8]. Additionally, the use of CF transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) modulators may increase the risk of biliary colic[9]. The population of patients with CF are aging and CFTR modulators are increasingly used, which are leading to a greater number of patients at risk for biliary and gallbladder disorders.

In patients without CF, symptomatic biliary disorders are managed surgically by cholecystectomy. However, few CF patients undergo cholecystectomy, due at least in part to concerns for perioperative complications[3,10]. The few published case series of cholecystectomy show an aggregate mortality rate of 4% (3/71) among patients with CF, which is considerably higher than the 0.15% mortality reported in the general population[6,8,10-15]. However, the CF surgical case series were completed over 25 years ago, and surgical technique and patient characteristics have changed dramatically since then. We hypothesized that the outcomes of cholecystectomy in a modern cohort of subjects with CF will be no different than the general population, especially when controlling for comorbidities. We aimed to evaluate the safety of chole

A retrospective analysis was performed using the Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS) (2002 to 2014), available through the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The NIS represents more than 35 million individual hospitalizations annually across the United States and is one of the largest publicly available databases. This database can be used to evaluate patient and hospital characteristics as well as resource utilization such as costs, mortality, and length of stay[16]. As the NIS is a publicly available database of de-identified patients, The Ohio State University Institutional Review Board deemed studies utilizing this resource as exempt.

Subjects were required to have a procedure code for cholecystectomy, defined as open, laparoscopic, or laparoscopic converted to open (Supplementary Table 1). Subjects were excluded if they were under the age of 18, pregnant, had cirrhosis, or underwent a partial cholecystectomy. Patients who underwent laparoscopic converted to open approach were categorized as open cholecystectomy. The cohorts were then defined by the presence or absence of CF diagnosis codes.

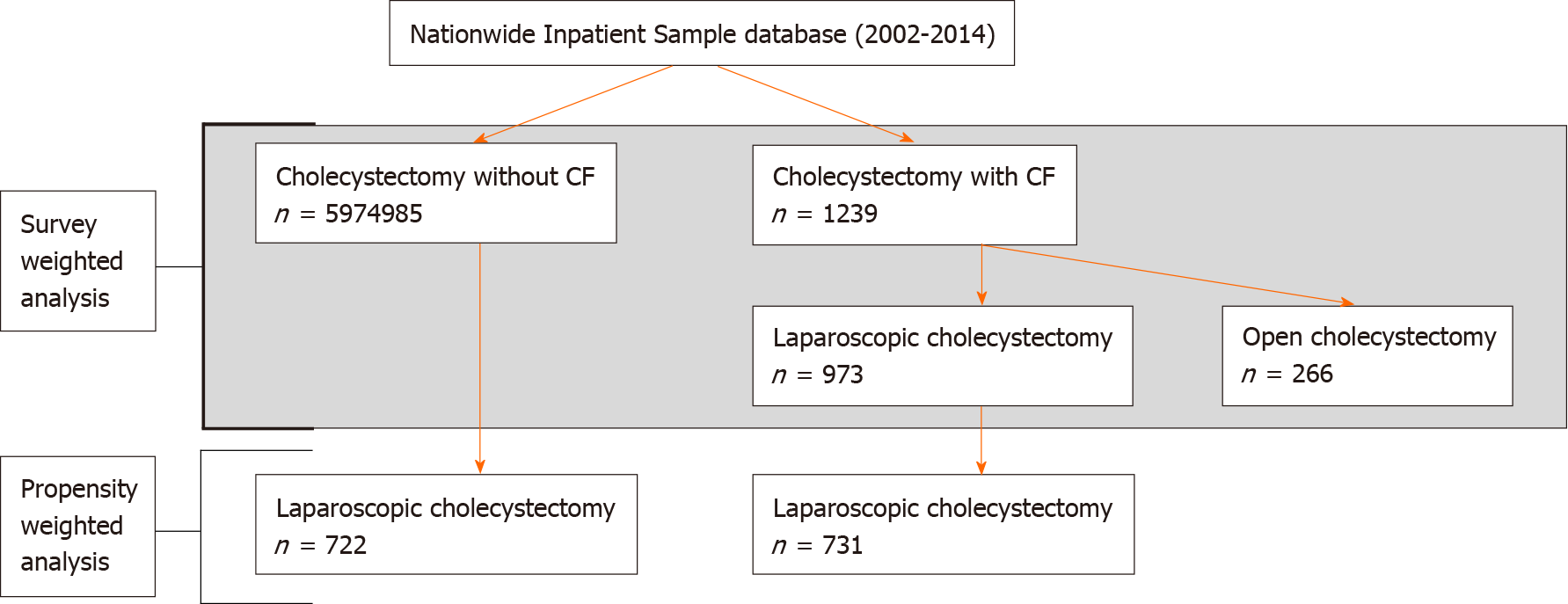

The primary outcome of interest was mortality following cholecystectomy. As secondary outcomes, we evaluated length of stay, cost of hospitalization, and the rates of post-operative complications based on a validated set of diagnosis and procedure codes (Supplementary Table 1)[17,18]. Additionally, we analyzed the indications for cholecystectomy among patients with CF using previously defined diagnosis codes (Supplementary Table 1)[19-21]. Patients with choledocholithiasis and gallstone pancreatitis were included in the category of gallstone disease without cholecystitis (Supplementary Table 1). All outcomes were compared between patients with and without CF using survey weighting and propensity weighting and between patients with CF who received open or laparoscopic cholecystectomy using univariate and multivariate analyses. A study flowchart of patient inclusion and analyses is presented in Figure 1.

Other variables evaluated include age, gender, race, income, type of insurance, hospital size, type of hospital, and hospital region. The presence of comorbid conditions were evaluated using the Elixhauser comorbidity index, which has been used widely since it was developed in 2005[22].

All analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, United States) on weighted data and accounted for the complex survey designs of the NIS. Differences between patient characteristics, hospital characteristics, and outcomes were compared between patients with and without CF through the use of chi-square tests for categorical variables and t-tests for continuous variables. Similar comparisons were made between the populations of patients with CF who underwent open or laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Multivariate linear regression models were created for length of stay and hospital costs using a stepwise selection process. Where less than 10 observations are recorded, the exact number is censored to protect subject privacy, per NIS regulations. Missing data is listed in Supplementary Table 2.

Among patients who underwent a laparoscopic cholecystectomy, propensity scores were calculated using a multivariable logistic regression model for CF containing all patient and hospital characteristics and indications for cholecystectomy as well as all individual Elixhauser comorbidities. The logistic regression model was weighted and accounted for all aspects of the complex survey design.

After deriving propensity scores (e) for each subject, propensity score weights were defined as 1 for subjects with CF and as e/(1-e) for subjects without CF. These propensity score weights were then multiplied by the original survey weights defined by HCUP to arrive at the new weights which were used in place of the original HCUP weights in the following propensity weighted analysis, as previously described[23]. After propensity weighting was applied, all variables were well balanced between the two groups. The propensity weights were then used to evaluate differences in outcomes between patients with and without CF.

From 2002 to 2014, a total of 5976224 adults underwent inpatient cholecystectomy, of which 1239 (0.021%) had CF (Table 1, Figure 1). Subjects with CF were younger and were more likely to be white, have private insurance, be treated at an urban teaching hospital, and have comorbid chronic respiratory failure (Table 1). A laparoscopic approach was used more often in CF subjects than in controls (78.6% vs 70.2%, P = 0.003) (Table 1). The indications for surgery between these groups were different: subjects with CF were less likely to undergo cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis (48.1% vs 60.4%, P < 0.001), but more likely to have gallstone disease without cholecystitis (26.6% vs 18.0%, P < 0.001) or biliary dyskinesia (5.0% vs 1.2%, P < 0.001) (Table 1). Mortality was not significantly different between those with CF and those without (≤ 0.81% vs 0.99%, P = 0.719) (Supplementary Table 3). Length of stay and total hospitalization costs were higher for CF patients than controls (10.1 d vs 5.4 d, P < 0.001; $27561 vs $14059, P < 0.001) (Supplementary Table 3).

| Without cystic fibrosis (n = 5974985) | With cystic fibrosis (n = 1239) | ||||

| n | % | n | % | P value | |

| Patient and hospital characteristics | |||||

| Age (mean ± SE) | 53.81 | 0.05 | 31.28 | 0.80 | < 0.001 |

| Gender | 0.342 | ||||

| Male | 2113648 | 35.45 | 475 | 38.35 | |

| Female | 3848224 | 64.55 | 764 | 61.65 | |

| Race | < 0.001 | ||||

| White | 3377462 | 68.16 | 917 | 90.92 | |

| Black | 486644 | 9.82 | 15 | 1.51 | |

| Hispanic | 784975 | 15.84 | 38 | 3.81 | |

| Other | 306042 | 6.18 | 38 | 3.75 | |

| Income quartile | 0.669 | ||||

| First | 1443591 | 26.81 | 270 | 23.36 | |

| Second | 1423075 | 26.43 | 322 | 27.83 | |

| Third | 1342530 | 24.94 | 313 | 27.06 | |

| Fourth | 1174730 | 21.82 | 251 | 21.76 | |

| Primary payer | < 0.001 | ||||

| Medicare | 2013023 | 33.76 | 255 | 20.62 | |

| Medicaid | 689680 | 11.57 | 215 | 17.34 | |

| Private insurance | 2550634 | 42.77 | 646 | 52.16 | |

| Other | 710118 | 11.91 | 122 | 9.88 | |

| Elixhauser co-morbidity score | 0.095 | ||||

| < 3 | 4425355 | 74.06 | 974 | 78.62 | |

| ≥ 3 | 1549630 | 25.94 | 265 | 21.38 | |

| Chronic respiratory failure | 16136 | 0.27 | 24 | 1.96 | < 0.001 |

| Hospital bed size | 0.044 | ||||

| Small | 744565 | 12.50 | 89 | 7.27 | |

| Medium | 1569622 | 26.36 | 306 | 24.87 | |

| Large | 3639976 | 61.13 | 835 | 67.86 | |

| Hospital location/teaching status | < 0.001 | ||||

| Rural | 786013 | 13.20 | 57 | 4.67 | |

| Urban non-teaching | 2724014 | 45.75 | 252 | 20.52 | |

| Urban teaching | 2444135 | 41.05 | 920 | 74.82 | |

| Hospital region | 0.184 | ||||

| Northeast | 1048152 | 17.54 | 210 | 16.93 | |

| Midwest | 1248121 | 20.89 | 335 | 27.00 | |

| South | 2369451 | 39.66 | 467 | 37.65 | |

| West | 1309262 | 21.91 | 228 | 18.42 | |

| Cholecystectomy approach | 0.003 | ||||

| Laparoscopic | 4192051 | 70.16 | 973 | 78.55 | |

| Open | 1782934 | 29.84 | 266 | 21.45 | |

| Indication for cholecystectomy1 | < 0.001 | ||||

| Acute cholecystitis | 3606140 | 60.35 | 597 | 48.14 | |

| Chronic cholecystitis | 317489 | 5.31 | 98 | 7.90 | |

| Gallstone disease without cholecystitis | 1077090 | 18.03 | 329 | 26.58 | |

| Biliary dyskinesia | 71204 | 1.19 | 62 | 5.03 | |

| Other | 903063 | 15.11 | 153 | 12.35 | |

After propensity weighting was applied to patients who underwent laparoscopic cholecystectomy, the variables were well balanced between groups (Supplementary Table 4). Hospital mortality was low among both groups, with less than 10 events observed (Table 2). Subjects with CF experienced a mean length of stay (LOS) of 9.4 d, compared to 5.2 d in those without CF (P < 0.001) (Table 2). Similarly, total hospital costs were greater for subjects with CF ($25891 vs $14103, P = 0.003) (Table 2). There was no difference between CF and controls in post-operative surgical complications (4.5% vs 2.3%, P = 0.094) or pulmonary complications (6.6% vs 4.1%, P = 0.109) (Table 2).

| Without cystic fibrosis (n = 722) | With cystic fibrosis (n = 731) | ||||

| n | % | n | % | P value | |

| Mortality1 | ≤ 10 | ≤ 1.39 | ≤ 10 | ≤ 1.37 | 0.662 |

| Length of stay (mean ± SE) | 5.18 | 0.33 | 9.36 | 0.89 | < 0.001 |

| Cost ($) (mean ± SE) | 14103 | 842 | 25891 | 3859 | 0.003 |

| Pulmonary complications | 29 | 4.05 | 49 | 6.64 | 0.109 |

| Surgical complications | 16 | 2.27 | 33 | 4.48 | 0.094 |

Of the 1239 patients with CF who underwent cholecystectomy, 973 (78.6%) had a laparoscopic approach. Compared to an open approach, patients with a laparoscopic cholecystectomy were more likely to be female, but other demographics were similar (Table 3). There was no significant difference in mortality (≤ 1.0% vs ≤ 3.8%, P = 0.286) but the LOS was longer and total hospital costs were greater in the open cholecystectomy group (14.5 d vs 8.9 d, P = 0.009; $43024 vs $23288, P = 0.005) (Supplementary Table 4). After adjusting for significant covariates, open route at surgery was associated with longer LOS (4.82 d, 95%CI: 0.82 d, 8.83 d, P = 0.018) and increased hospital costs ($18449, 95%CI: $5582, $31316, P = 0.005) (Table 4 and Supplementary Table 5). There were insufficient observations of mortality and post-operative complications to fit a multivariate model for these outcomes.

| Laparoscopic CCY (n = 973) | Open CCY (n = 266) | ||||

| n | % | n | % | P value | |

| Patient and hospital characteristics | |||||

| Age (mean ± SE) | 30.78 | 0.86 | 33.11 | 1.95 | 0.272 |

| Gender | 0.005 | ||||

| Male | 330 | 33.92 | 145 | 54.60 | |

| Female | 643 | 66.08 | 121 | 45.40 | |

| Race | 0.911 | ||||

| White | 718 | 90.92 | 199 | 90.93 | |

| Black | ≤ 10 | ≤ 1.03 | ≤ 10 | ≤ 3.76 | |

| Hispanic | 29 | 3.65 | ≤ 10 | ≤ 3.76 | |

| Other | 33 | 4.13 | ≤ 10 | ≤ 3.76 | |

| Income quartile | 0.110 | ||||

| First | 210 | 23.22 | 60 | 23.86 | |

| Second | 221 | 24.47 | 100 | 39.95 | |

| Third | 264 | 29.20 | 48 | 19.34 | |

| Fourth | 209 | 23.11 | 42 | 16.85 | |

| Primary payer | 0.265 | ||||

| Medicare | 221 | 22.73 | 34 | 12.86 | |

| Medicaid | 177 | 18.23 | 37 | 14.07 | |

| Private insurance | 482 | 49.56 | 164 | 61.69 | |

| Other | 92 | 9.47 | 30 | 11.38 | |

| Elixhauser co-morbidity score | 0.311 | ||||

| < 3 | 778 | 79.93 | 196 | 73.81 | |

| ≥ 3 | 195 | 20.07 | 70 | 26.19 | |

| Chronic respiratory failure | 24 | 2.50 | 0 | 0.00 | - |

| Hospital bed size | 0.244 | ||||

| Small | 71 | 7.29 | 19 | 7.21 | |

| Medium | 219 | 22.58 | 87 | 33.34 | |

| Large | 679 | 70.13 | 155 | 59.45 | |

| Hospital location/teaching status | 0.476 | ||||

| Rural | 53 | 5.45 | ≤ 10 | ≤ 3.76 | |

| Urban non-teaching | 193 | 19.94 | 59 | 22.67 | |

| Urban teaching | 723 | 74.61 | 197 | 75.56 | |

| Hospital region | 0.812 | ||||

| Northeast | 167 | 17.15 | 43 | 16.12 | |

| Midwest | 258 | 26.53 | 76 | 28.73 | |

| South | 378 | 38.85 | 88 | 33.27 | |

| West | 170 | 17.47 | 58 | 21.88 | |

| Indication for cholecystectomy1 | |||||

| Acute cholecystitis | 527 | 54.17 | 69 | 26.07 | |

| Chronic cholecystitis | 84 | 8.61 | 14 | 5.28 | |

| Gallstone disease without cholecystitis | 285 | 29.25 | 45 | 16.82 | |

| Biliary dyskinesia2 | 58 | 5.95 | ≤ 10 | ≤ 3.76 | |

| Other | 20 | 2.02 | 133 | 50.18 | |

| Length of stay | Hospitalization cost | |||||

| Days | 95%CI | P value | $ | 95%CI | P value | |

| Open cholecystectomy | 4.82 | (0.82, 8.83) | 0.018 | 18449 | (5582, 31316) | 0.005 |

| Elixhauser co-morbidity score ≥ 3 | 8.35 | (4.28, 12.43) | < 0.001 | 28344 | (10548, 46141) | 0.002 |

| Hospital location/teaching status | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | ||||

| Rural | -5.88 | (-11.53, -0.24) | -13801 | (-22490, -5111) | ||

| Urban non-teaching | -3.69 | (-5.71, -1.68) | -13709 | (-20684, -6734) | ||

| Urban teaching | Ref. | Ref. | ||||

More patients with CF are reaching adulthood due to advances in CF care and CFTR modulators are increasingly used. With this, clinicians are likely to see an increasing prevalence of biliary disorders for which cholecystectomy will be considered as a definitive treatment. Therefore, it is important to clarify the safety of cholecystectomy. In this study, we used a nationally-representative database to evaluate the post-operative outcomes among adult patients with CF who undergo cholecystectomy. Importantly, we found that cholecystectomy had very low in-hospital mortality that was not significantly different from the general population. The surgical indications and approach were different between patients with and without CF. Open cholecystectomy was independently associated with longer LOS and greater hospital costs compared to laparoscopic approach. Finally, there is increased healthcare utilization among patients with CF compared to a propensity weighted cohort following laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

Our data shows a low mortality rate in a large and nationally representative cohort of CF patients, comparable to previous case series of cholecystectomy among CF patients. Aggregate data from case series show no deaths out of 12 patients who underwent laparoscopic surgery and 3/59 (5.1%) who underwent open chole

Post-operative pulmonary decompensation and infection has been reported in previous case series, with an overall incidence of 7.0% (5/71) that is similar to our study[6,8,10-13,15]. To mitigate this risk, chest physiotherapy and antibiotics were used pre- and post-operatively. One group targeted pre-operative pulmonary function tests at the “highest level attained in the past 2 years, or until a prolonged period of therapy reaches a plateau of improvement” for elective surgery[10]. Increased pulmonary complications after open cholecystectomy may be attributed to deran

While the incidence of post-cholecystectomy pulmonary complications has been described, the risk of surgical complications including soft tissue infections, perforation during surgery and need for recurrent surgery in CF compared to the general population has not been previously reported. We demonstrate an increased risk of surgical complications in patients with CF compared to the general population in the survey weighted cohort, and an increased risk with open compared to laparoscopic cholecystectomy among patients with CF. In the propensity weighted analysis, we found no significant difference in the rate of surgical complications. Patients with CF have an increased risk of infections with drug resistant bacteria, which may place this population at higher risk of infection after surgical intervention as these organisms may not be treated by routine pre-operative antibiotics[27].

Our study has several limitations inherent to the use of a large database, such as the potential for coding errors. Additionally, we cannot account for characteristics that are not included in the NIS which may influence outcomes, such as medication use, nutritional status, and baseline pulmonary function, nor can we evaluate survival beyond the inpatient period. Lastly, there may be selection bias, as only patients with acceptable surgical risk would have undergone cholecystectomy. Due to these limitations, “causality” cannot be inferred from large database analyses. However, in the absence of a prospectively collected surgical registry among patients with CF, the NIS remains an excellent data source due to its large number of observations and sophisticated sampling design. The NIS included 1239 inpatient cholecystectomies among patients with CF which greatly outnumbers the 71 cases reported in the literature to date. Additionally the NIS represents national demographics so the reported outcomes are likely to be generalizable to similar CF patients encountered in clinical practice. Finally, the volume of cholecystectomy in the control population allowed for a propensity weighted analysis to approximate a randomized trial, which could not be reasonably accomplished outside of a large database.

Cholecystectomy among adult patients with CF did not carry an increased risk of in-hospital mortality compared to controls. Length of stay and hospital costs are higher in patients with CF and there is a higher risk of post-operative surgical complications and a tendency to develop more pulmonary complications, although this risk of complications is no longer seen when demographic and health variables are taken into account. A laparoscopic approach is safer and reduces healthcare utilization compared to an open approach in adults with CF. These results should inform the discussion between clinicians and patients with CF when cholecystectomy is considered.

Symptomatic biliary disorders are common in cystic fibrosis (CF) and may become more common now that patients with CF are living longer. Biliary disorders are often managed with cholecystectomy but this surgery carries high risk of morbidity and mortality among adults with CF. However, the reported rate of complications is based on older studies, and may not represent modern surgical outcomes.

Currently, there is insufficient data examining the safety of cholecystectomy among adults with CF using modern surgical techniques.

To investigate the outcomes of inpatient cholecystectomy among adults with and without CF.

The Nationwide Inpatient Sample was used to collect data on inpatient cholecystectomies between 2002 and 2014. Subjects without CF were matched 1:1 to subjects with CF, accounting for over 20 variables including age, sex, and comorbidities.

Among patients with CF, 1239 cholecystectomies were performed during the study period. Open cholecystectomy was independently associated with an $18449 increase in hospital costs (P = 0.005) and a 4.8 d longer length of stay (P = 0.018) compared to laparoscopic cholecystectomy. The mortality rate among patients with CF was < 0.81%, which was similar to the mortality rate among patients without CF (P = 0.719). Similarly, there was no significant difference in mortality or post-operative surgical complications (4.5% vs 2.3%, P = 0.094) or pulmonary complications (6.6% vs 4.1%, P = 0.109) after laparoscopic cholecystectomy between patients with and without CF in the propensity weighted analysis.

With modern anesthesia and surgical techniques, cholecystectomy is equally safe for patients with and without CF.

Cholecystectomy may be increasingly considered for the management of biliary symptoms among adults with CF. Future research will need to clarify if there are unique indications for cholecystectomy among patients with CF.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: United States

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Tebala GD S-Editor: Zhang H L-Editor: A P-Editor: Liu JH

| 1. | O'Sullivan BP, Freedman SD. Cystic fibrosis. Lancet. 2009;373:1891-1904. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1015] [Cited by in RCA: 1011] [Article Influence: 63.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Elborn JS. Cystic fibrosis. Lancet. 2016;388:2519-2531. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1068] [Cited by in RCA: 1245] [Article Influence: 138.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Cystic Fibrosis Foundation Patient Registry. Annual Data Report 2018. Available from: https://cff.org/Research/Researcher-Resources/Patient-Registry/2018-Patient-Registry-Annual-Data-Report.pdf. |

| 4. | Assis DN, Debray D. Gallbladder and bile duct disease in Cystic Fibrosis. J Cyst Fibros. 2017;16 Suppl 2:S62-S69. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Jebbink MC, Heijerman HG, Masclee AA, Lamers CB. Gallbladder disease in cystic fibrosis. Neth J Med. 1992;41:123-126. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Cogliandolo A, Patania M, Currò G, Chillè G, Magazzù G, Navarra G. Postoperative outcomes and quality of life in patients with cystic fibrosis undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a retrospective study. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2011;21:179-183. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Quattrucci S, Angelico M, Stancati M, Bertasi S, Cantusci D, De Sanctis A, Antonelli M. Hepatobiliary involvement in adolescents and adults with cystic fibrosis. Acta Univ Carol Med (Praha). 1990;36:180-182. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Stern RC, Rothstein FC, Doershuk CF. Treatment and prognosis of symptomatic gallbladder disease in patients with cystic fibrosis. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1986;5:35-40. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Safirstein J, Grant JJ, Clausen E, Savant D, Dezube R, Hong G. Biliary disease and cholecystectomy after initiation of elexacaftor/ivacaftor/tezacaftor in adults with cystic fibrosis. J Cyst Fibros. 2021;20:506-510. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Snyder CL, Ferrell KL, Saltzman DA, Warwick WJ, Leonard AS. Operative therapy of gallbladder disease in patients with cystic fibrosis. Am J Surg. 1989;157:557-561. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Baldwin DR, Balfour T, Knox AJ. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy in patients with cystic fibrosis. Respir Med. 1993;87:223-224. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Anagnostopoulos D, Tsagari N, Noussia-Arvanitaki S, Sfougaris D, Valioulis I, Spyridakis I. Gallbladder disease in patients with cystic fibrosis. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 1993;3:348-351. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Shen GK, Tsen AC, Hunter GC, Ghory MJ, Rappaport W. Surgical treatment of symptomatic biliary stones in patients with cystic fibrosis. Am Surg. 1995;61:814-819. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Sandblom G, Videhult P, Crona Guterstam Y, Svenner A, Sadr-Azodi O. Mortality after a cholecystectomy: a population-based study. HPB (Oxford). 2015;17:239-243. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | McGrath DS, Short C, Bredin CP, Kirwan WO, Rooney E, Meeke R. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy in adult cystic fibrosis. Ir J Med Sci. 1997;166:70-71. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | HCUP Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS). Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP). 2002-2013. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, MD. Available from: https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/nisoverview.jsp. |

| 17. | Lawthers AG, McCarthy EP, Davis RB, Peterson LE, Palmer RH, Iezzoni LI. Identification of in-hospital complications from claims data. Is it valid? Med Care. 2000;38:785-795. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 288] [Cited by in RCA: 322] [Article Influence: 12.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Murphy MM, Ng SC, Simons JP, Csikesz NG, Shah SA, Tseng JF. Predictors of major complications after laparoscopic cholecystectomy: surgeon, hospital, or patient? J Am Coll Surg. 2010;211:73-80. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Aziz H, Pandit V, Joseph B, Jie T, Ong E. Age and Obesity are Independent Predictors of Bile Duct Injuries in Patients Undergoing Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy. World J Surg. 2015;39:1804-1808. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Malli A, Durkin C, Groce JR, Hinton A, Conwell DL, Krishna SG. Unavailability of Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiography Adversely Impacts Hospital Outcomes of Acute Biliary Pancreatitis: A National Survey and Propensity-Matched Analysis. Pancreas. 2020;49:39-45. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Bielefeldt K. The rising tide of cholecystectomy for biliary dyskinesia. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2013;37:98-106. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Quan H, Sundararajan V, Halfon P, Fong A, Burnand B, Luthi JC, Saunders LD, Beck CA, Feasby TE, Ghali WA. Coding algorithms for defining comorbidities in ICD-9-CM and ICD-10 administrative data. Med Care. 2005;43:1130-1139. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6122] [Cited by in RCA: 8386] [Article Influence: 419.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Dugoff EH, Schuler M, Stuart EA. Generalizing observational study results: applying propensity score methods to complex surveys. Health Serv Res. 2014;49:284-303. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 424] [Cited by in RCA: 365] [Article Influence: 33.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Tumin D, Hayes D Jr, Kirkby SE, Tobias JD, McKee C. Safety of endoscopic sinus surgery in children with cystic fibrosis. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2017;98:25-28. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Bablekos GD, Michaelides SA, Analitis A, Charalabopoulos KA. Effects of laparoscopic cholecystectomy on lung function: a systematic review. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:17603-17617. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 26. | Coccolini F, Catena F, Pisano M, Gheza F, Fagiuoli S, Di Saverio S, Leandro G, Montori G, Ceresoli M, Corbella D, Sartelli M, Sugrue M, Ansaloni L. Open versus laparoscopic cholecystectomy in acute cholecystitis. Systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Surg. 2015;18:196-204. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 276] [Cited by in RCA: 248] [Article Influence: 24.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Akil N, Muhlebach MS. Biology and management of methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus in cystic fibrosis. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2018;53:S64-S74. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |