Published online Aug 16, 2021. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v13.i8.345

Peer-review started: April 23, 2021

First decision: June 7, 2021

Revised: June 21, 2021

Accepted: July 5, 2021

Article in press: July 5, 2021

Published online: August 16, 2021

Processing time: 110 Days and 9 Hours

Percutaneous transhepatic gallbladder drainage has been the most frequently performed treatment for acute cholecystitis for patients who are not candidates for surgery. Endoscopic transpapillary gallbladder drainage (ETGBD) has evolved into an alternative treatment. There have been numerous retrospective and prospective studies evaluating ETGBD for acute cholecystitis, though results have been variable.

To evaluate the efficacy and safety of ETGBD in the treatment of inoperable patients with acute cholecystitis.

We performed a systematic review of major literature databases including PubMed, OVID, Science Direct, Google Scholar (from inception to March 2021) to identify studies reporting technical and clinical success, and post procedure adverse events in ETGBD. Weighted pooled rates were then calculated using fixed effects models for technical and clinical success, and post procedure adverse events, including recurrent cholecystitis.

We found 21 relevant articles that were then included in the study. In all 1307 patients were identified. The pooled technical success rate was 82.62% [95% confidence interval (CI): 80.63-84.52]. The pooled clinical success rate was found to be 94.87% (95%CI: 93.54-96.05). The pooled overall complication rate was 8.83% (95%CI: 7.42-10.34). Pooled rates of post procedure adverse events were bleeding 1.03% (95%CI: 0.58-1.62), perforation 0.78% (95%CI: 0.39-1.29), peritonitis/bile leak 0.45% (95%CI: 0.17-0.87), and pancreatitis 1.98% (95%CI: 1.33-2.76). The pooled rates of stent occlusion and migration were 0.39% (95%CI: 0.13-0.78) and 1.3% (95%CI: 0.75-1.99) respectively. The pooled rate of cholecystitis recurrence following ETGBD was 1.48% (95%CI: 0.92-2.16).

Our meta-analysis suggests that ETGBD is a feasible and efficacious treatment for inoperable patients with acute cholecystitis.

Core Tip: We offer the most updated meta-analysis evaluating the efficacy, feasibility and safety of endoscopic transpapillary gallbladder drainage for the treatment of inoperable acute cholecystitis. We included 21 studies in our analysis. Our results conclude that this modality of gallbladder drainage is safe and efficacious.

- Citation: Jandura DM, Puli SR. Efficacy and safety of endoscopic transpapillary gallbladder drainage in acute cholecystitis: An updated meta-analysis. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2021; 13(8): 345-355

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v13/i8/345.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v13.i8.345

Cholelithiasis is a common condition that affects 6% of men and 9% of women in the United States[1]. Acute cholecystitis is a syndrome of right upper quadrant abdominal pain, fevers and leukocytosis that is associated with inflammation of the gallbladder. Occurring in about 6%-11% of patients with symptomatic gallstones, it is the most common gallbladder syndrome[2]. The standard of care treatment for acute cholecy

Percutaneous drainage is well established in the literature with strong technical success rates of nearly 97%, and with more variable clinical response rates ranging from 56%-100%[3-5]. Though effective, complications related to externalized drainage including bile leakage, peritonitis, bleeding and catheter misplacement/removal have been noted[6]. Patient satisfaction and quality of life have also been of concern, with patient discomfort occurring in up to 25% of patients[7]. Coagulopathy and decompen

Endoscopic techniques for gallbladder drainage have been evaluated in inoperable patients with cholecystitis who are not suitable for percutaneous drainage. Two endoscopic approaches to gallbladder drainage exist, they include a transmural approach performed with endoscopic ultrasound (EUS), and endoscopic transpapillary gallbladder drainage (ETGBD) which utilizes endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP). EUS guided gallbladder drainage was first described in 2007, with well-established efficacy. Technical and clinical success rates of 84.6%-100% and 86.7%-100% respectively have been demonstrated[12,13]. Drawbacks, such as the need for a high level of expertise, procedure costs and the risk of adverse events in the setting of technical failure, have been noted. The development of lumen opposing stents (LAMS) has improved the feasibility and efficacy and has helped to decrease the rate of procedure related complications. Nevertheless, there is uncertainly of the effects of retained LAMS and its contribution to adverse events as well as its effect on future surgical options.

Transpapillary gallbladder drainage is an important option for inoperable patients requiring treatment of acute cholecystitis. It consists of ERCP bile duct cannulation followed by endoscopic transpapillary gallbladder stenting or endoscopic nasobiliary gallbladder drainage (ENGBD). Both approaches have been useful in patients with concomitant choledocholithiasis or in the presence of biliary stricture. Unlike ENGBD, a transpapillary approach has evolved as an especially advantageous method due to its relatively non-invasive nature with improved patient quality of life without the need for externalized drainage. Drawbacks to this method include the potential for post ERCP complications, along with the technical difficulty of the procedure itself, though there have been variable results in the literature. We performed a systematic review including more recent studies evaluating ETGBD in inoperable patients with acute cholecystitis. We present an updated meta-analysis evaluating the technical and clinical success of ETGBD. We also evaluate the safety of ETGBD by analyzing pooled rates of procedural adverse events.

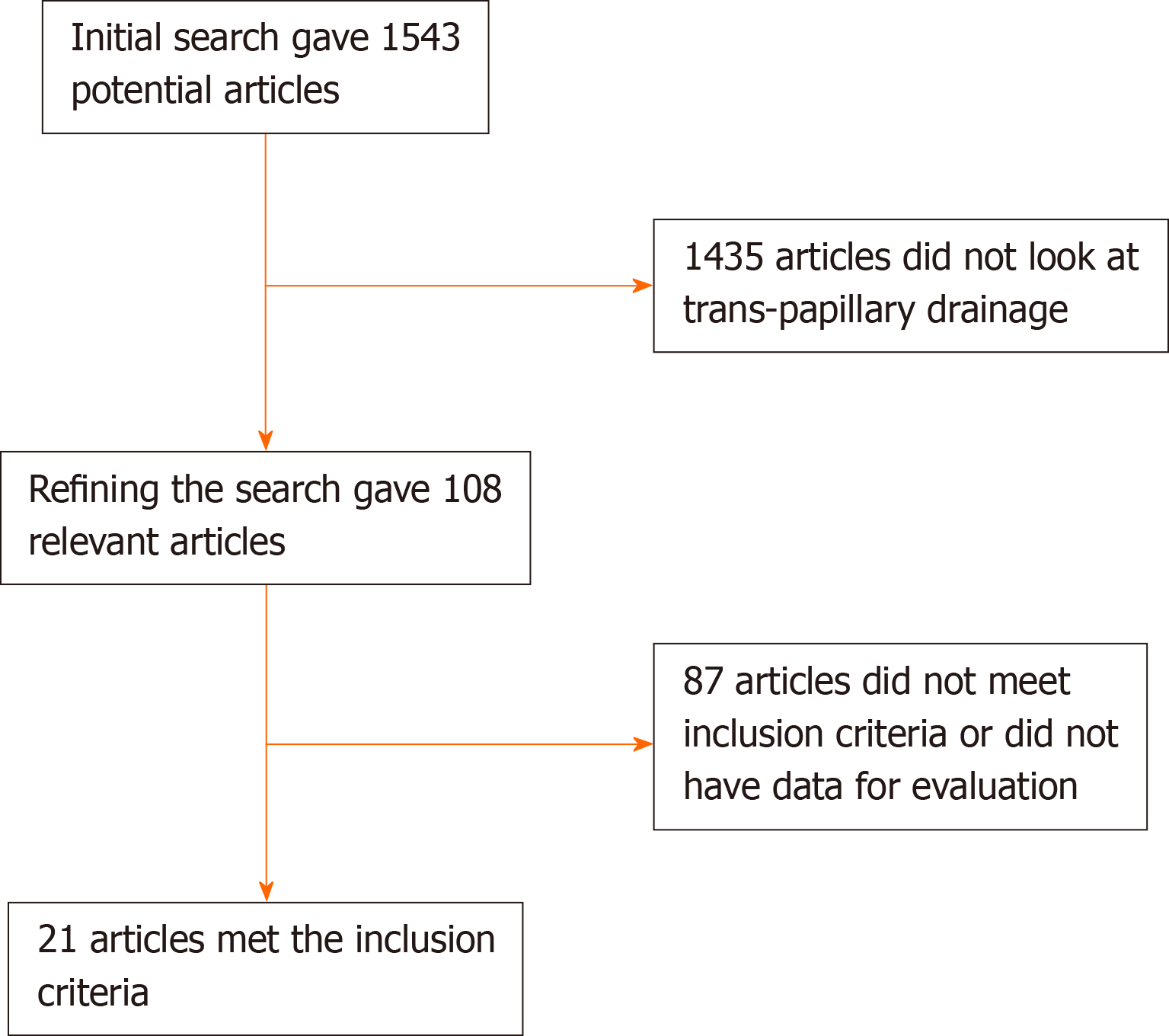

We performed a literature search using the electronic database engines PubMed, OVID, ScienceDirect, Google scholar from inception to March 2021 to identify published articles and reports which addressed the use of ETGBD as treatment for acute cholecystitis. The search terms “endoscopic transpapillary gallbladder drainage”, “acute cholecystitis”, “complications”, “technical success”, “clinical success”, “adverse events” in different combinations were used. The reference lists of eligible studies were reviewed to identify additional studies. The retrieved studies were carefully examined to exclude potential duplicates or overlapping data. Resultant titles and abstracts were selected from the initial search, they were scanned, and the full papers of potential eligible studies were reviewed.

The relevance of the studies was initially screened based on title, abstract and the full manuscript. Published studies were eligible for inclusion if they reported the use of ETGBD for the treatment of acute cholecystitis. Studies that evaluated technical and clinical success, along with procedure related adverse events were included. Articles were excluded if they were not available in English, or if they did not have reported outcomes. In studies that compared multiple methods of treatment for acute cholecystitis, data from the cohort of patients who underwent EGTBD were collected and analyzed. Each article title and abstract was reviewed by two investigators (Jandura DM and Puli SR). They obtained full articles that met the inclusion and exclusion criteria, and after an independent review of the full content of each article, they extracted the data. Any differences were resolved by mutual agreement. The agreement between reviewers gave a Cohen’s κ 1.0.

The following data was independently abstracted into a standardized form: Study characteristics (primary author, year of publication), study design, baseline characteristics of study population (number of patients enrolled, patient demographics) and intervention details (procedure indications) and outcomes (technical and clinical success, adverse events). The risk of bias was rated by two authors independently.

The primary outcome of interest was assessment of ETGBD efficacy in terms of technical and clinical success. Clinical success was calculated based on the cohort of patients that achieved technical success in each study. The secondary outcomes that were assessed were overall and individual procedure related adverse events, and the rates of recurrent cholecystitis following the intervention.

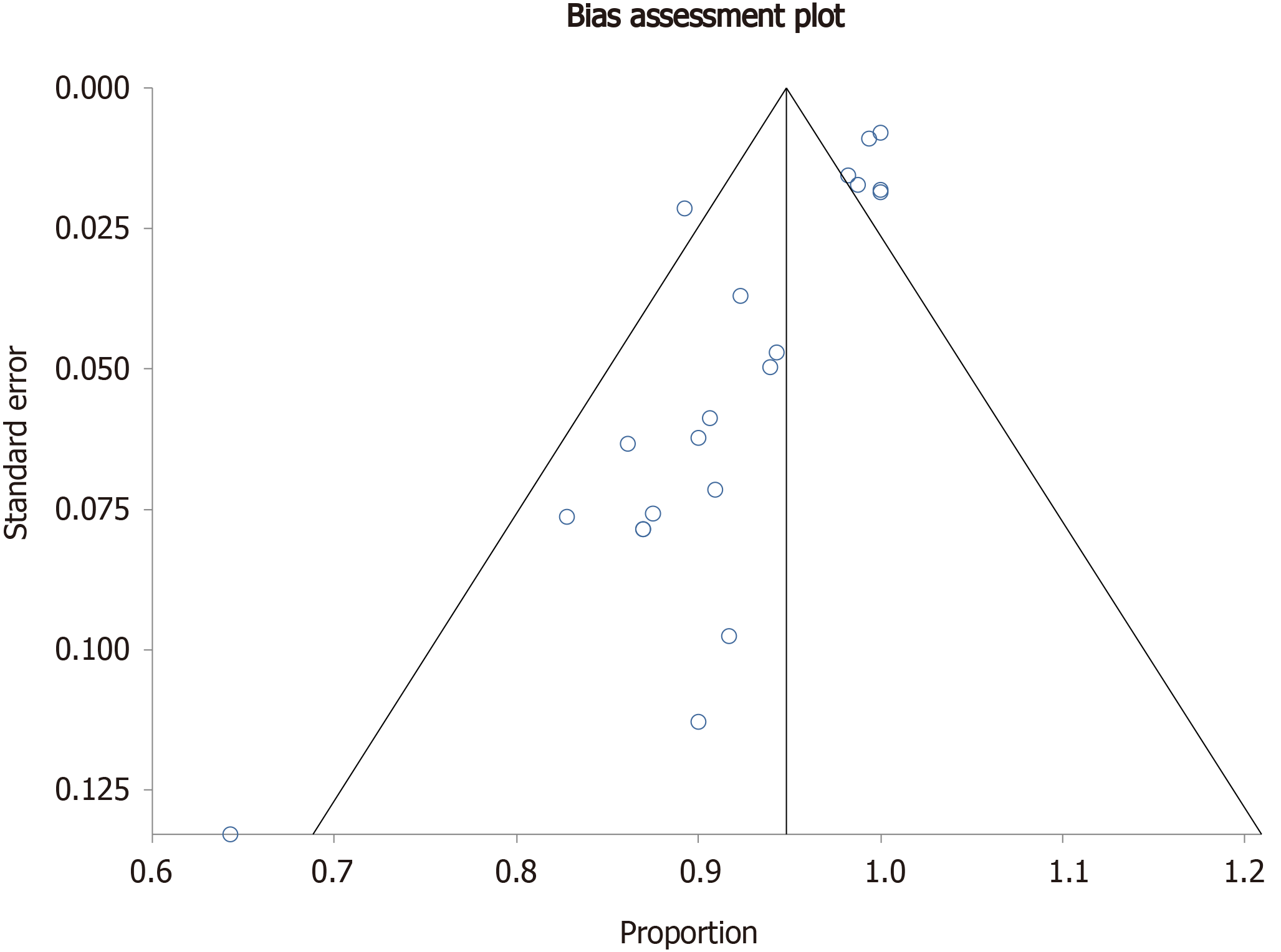

This meta-analysis was performed by calculating pooled proportions. First, the individual study proportions was transformed into a quantity using a Freeman-Tukey variant of the arcsine square root transformed proportion. The pooled proportion was calculated as the back-transform of the weighted mean of the transformed proportions, using inverse arcsine variance weights for the fixed effects model and DerSimonian-Laird weights for the random effects model[14,15]. Forest plots were drawn to show the point estimates in each study in relation to the summary pooled estimate. The width of the point estimates in the forest plots indicates the assigned weight to that study. The effect of publication and selection bias on the summary estimates was tested by the Harboud-Egger indicator[16]. Also, funnel plots were constructed to evaluate potential publication bias[17,18].

In summary, 21 studies identified by our search using the literature databases were included for our analysis. A flow diagram of this systematic review is included in Figure 1.

In all, 8 studies were performed in Japan, 6 were performed in the United States, and 4 were performed in South Korea. 3 of the remaining studies included in our meta-analysis were originally performed in Germany, Denmark and Italy. Most of the studies were retrospective, however prospective and one random controlled trial was included.

A total of 1307 patients from 21 studies were included in the meta-analysis. In this meta-analysis, 61.44% of the patients included were males and 38.56% were females. The median age of study subject was 68.41 (range: 48.5-79.7).

ETGBD was performed in inoperable patients with acute cholecystitis with placement of a double pigtail stent in 57.1% of studies. Plastic stents were used in 40.0% of studies. Nasobiliary stenting was performed in 45.0% of the studies included in the meta-analysis.

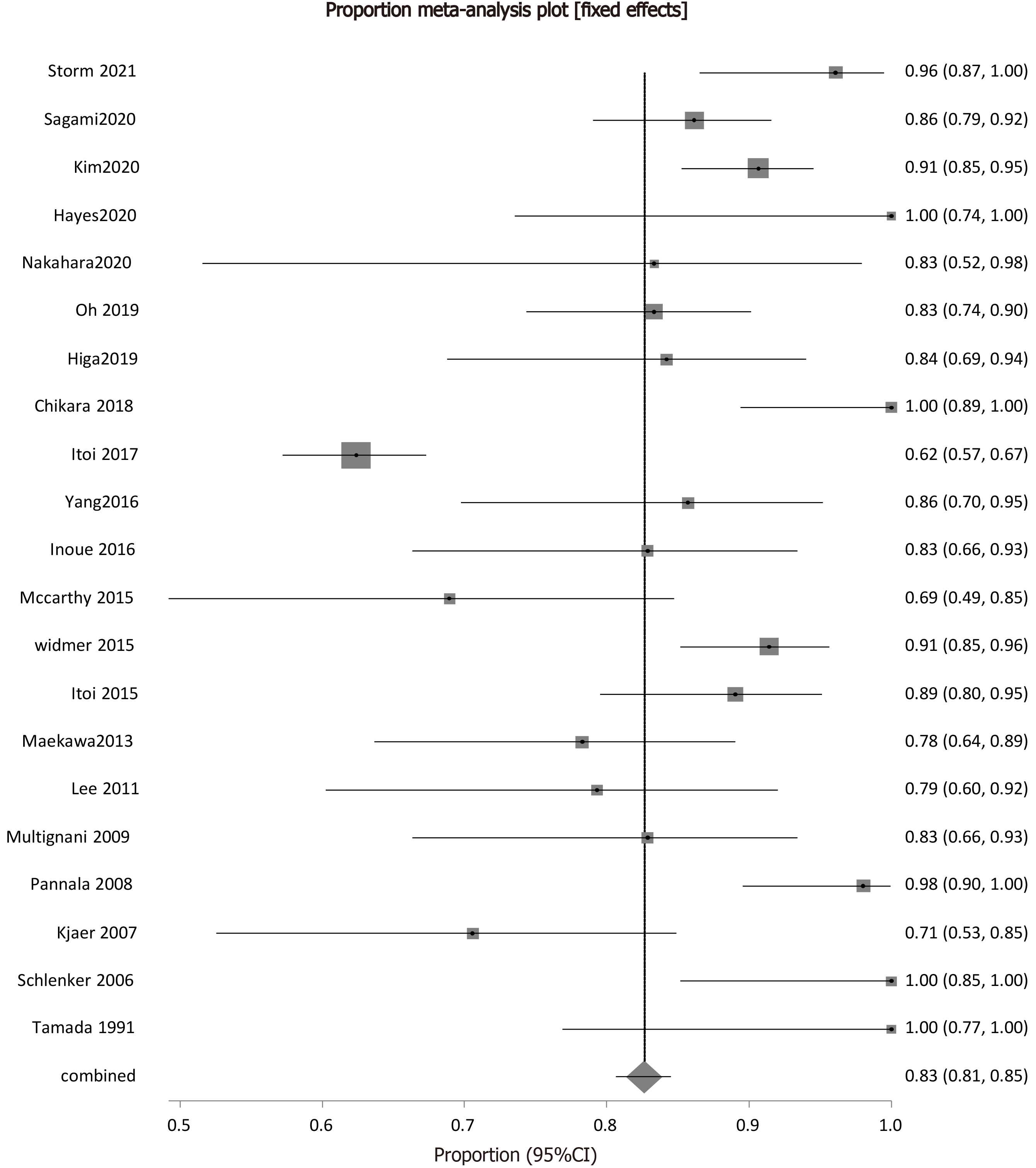

Technical success was reported by all the studies included in the analysis. The prevalence of successfully performed procedures ranged from 70.59%-100%. The pooled rate of technical success of ETGBD was 82.62% [95% confidence interval (CI): 80.63-84.52]. The individual study rates and the pooled proportion of technical success is shown as a forest plot in Figure 2.

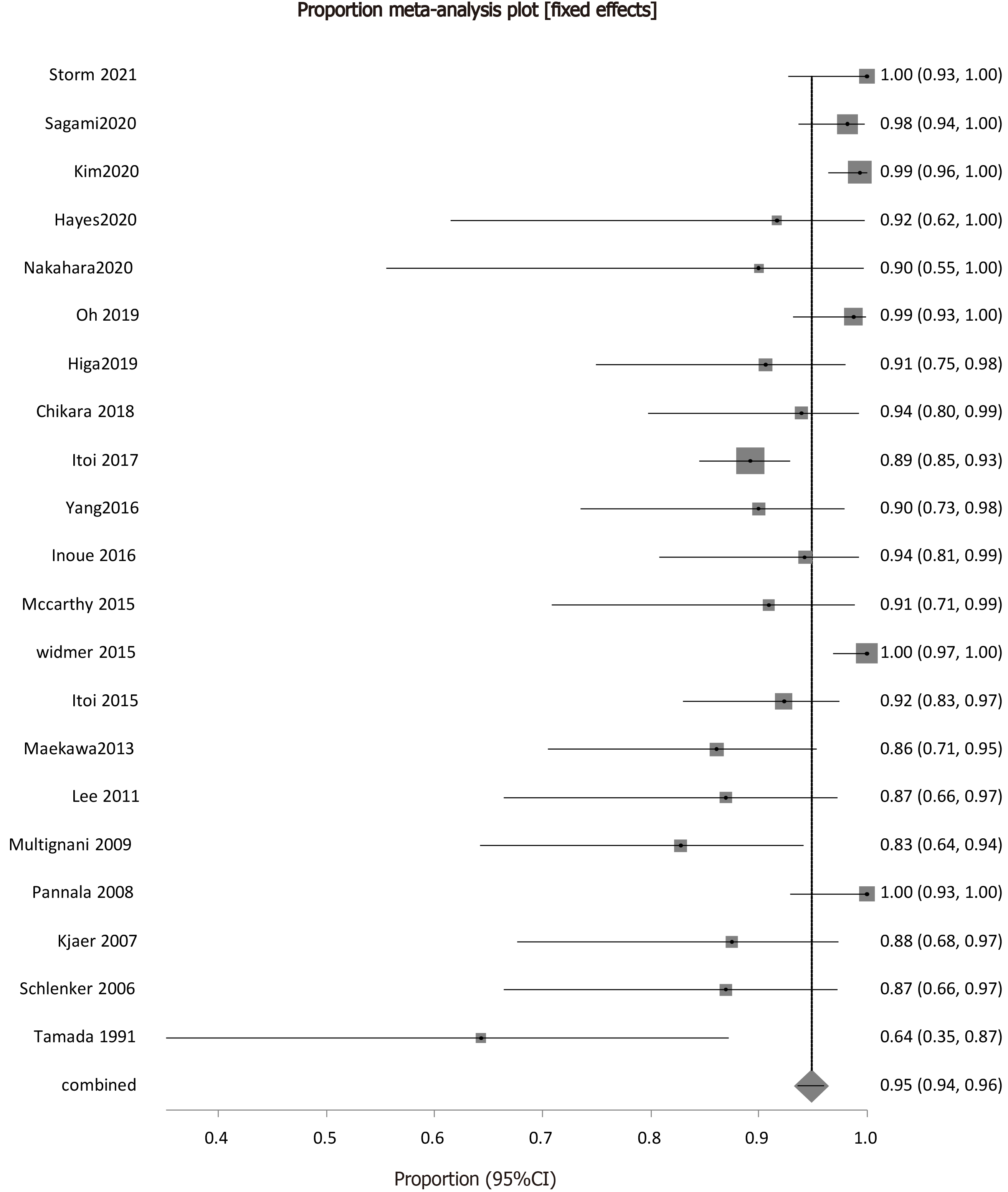

Procedure efficacy, as represented by clinical success was described by all the studies included in the analysis. Prevalence of ETGBD efficacy in successful treatment of cholecystitis ranged from 64.29%-100%. The pooled proportion of clinical success of ETGBD was 94.87% (95%CI: 93.54-96.05). Figure 3 shows the forest plot of the pooled proportion of clinical success.

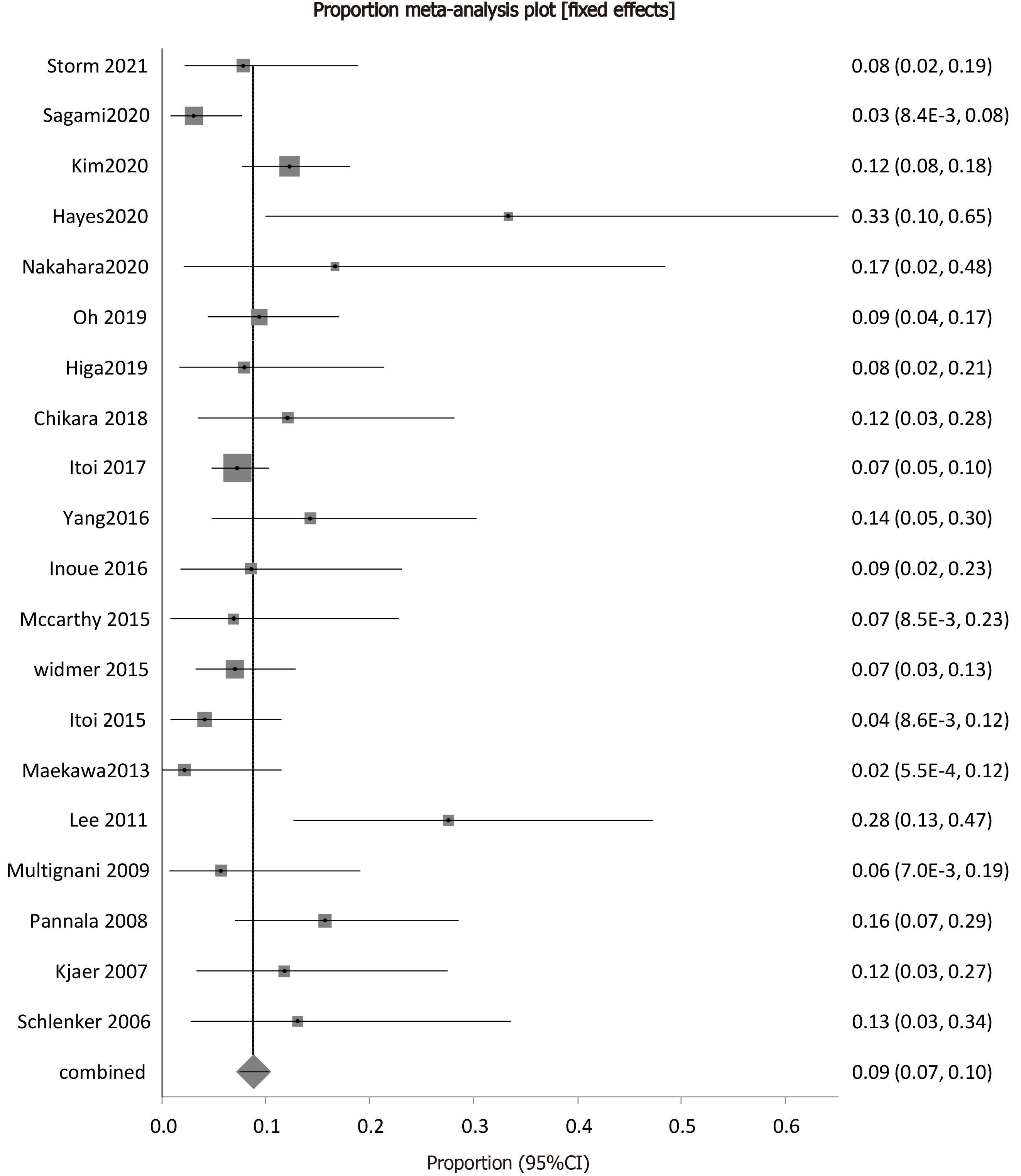

The overall pooled rate of post procedural complications was 8.83% (95%CI: 7.42-10.34). The forest plot depicting the pooled proportion of complications is in Figure 4. The pooled proportion of patients with bleeding as an adverse event following ETGBD was 1.03% (95%CI: 0.58-1.62). Pooled proportion of patients with perforation as an adverse event following ETGBD was 0.78% (95%CI: 0.39-1.29). Peritonitis/bile leak as an adverse event following ETGBD was calculated as a pooled proportion and was 0.45% (95%CI: 0.17-0.87). The pooled proportion of patients with pancreatitis following ETGBD was 1.98% (95%CI: 1.33-2.76).

Stent related procedure complications were also featured in the analysis as adverse events in all the included studies. They included both stent occlusion and stent migration. The pooled proportion of patients with stent occlusion following ETGBD was 0.39% (95%CI: 0.13-0.78). The pooled proportion of patients with stent migration was 1.3% (95%CI: 0.75-1.99).

Recurrent cholecystitis was also included as a secondary outcome measure. There were 6 studies which reported a recurrence of cholecystitis following ETGBD. The pooled proportion of patients with recurrent cholecystitis following ETGBD was 1.48% (95%CI: 0.92-2.16).

Publication bias calculation using the Harbord-Egger bias indicator gave a value of -1.61 (95%CI: -4.70-1.49) (P = 0.29), indicating that there was no publication bias. The funnel plot in Figure 5 shows no publication bias for ETGBD clinical success.

Cholecystectomy is the standard of care for the treatment of acute cholecystitis, however a subset of patients exists with co-morbidities or poor clinical status that are not candidates for surgery. Based on Tokyo guidelines from 2018, the standard non-surgical approach recommendation for high-risk patients has been percutaneous guided gallbladder drainage[19]. It has remained the most frequently used intervention for inoperable patients due to the vast procedural expertise that exists as well as its significant representation within the literature. The management of cholecystitis has evolved to include endoscopic methods of treatment, and choosing the appropriate intervention requires consideration of multiple factors including patient co-morbidities and preferences, technical factors, and local expertise. Endoscopic therapies have been advantageous over percutaneous drainage when tolerability of externalized drainage is an issue due to patient discomfort and given the potential for these drains to migrate, occlude or become secondarily infected. Other patient factors such as ascites or coagulopathy also need to be considered. Technical factors such as suspected biliary obstruction due to choledocholithiasis and biliary stricture, also support the preferential use of transpapillary gallbladder drainage.

Transpapillary drainage can be technically challenging, specifically due to the difficult nature of cannulation of the bile duct and traversal of the cystic duct. Our pooled rates of technical and clinical success were 83% and 95% respectively. Rates of initial failure are not negligible, however if successfully performed the vast majority of patients found clinical success. Studies have shown that centers with high volume and expertise have benefited from their increased experience, with improved technical success rates. Kjaer et al[20] demonstrated an improvement in technical success from 50% in the first 4 years of the study to 89% in the final 5 years of the study, indicating that there is a learning curve that could be overcome with experience. Prior studies have demonstrated similar results when evaluating efficacy of endoscopic drainage in regards to technical and clinical success compared to percutaneous methods[21], though further comparison trials are required.

Lyu et al[23] demonstrated that the adverse event and mortality rates amongst EUS guided gallbladder drainage, transpapillary gallbladder drainage and percutaneous gallbladder drainage were comparable. Nonetheless, post-operative complications related to endoscopic interventions such as EUSGBD and ETGBD tended to have higher risk adverse events that had a higher propensity to lead to death, such as perforation, bleeding, and pancreatitis. Our overall pooled complication rate was about 9%, with the highest being pooled rates of pancreatitis. ERCP related complications have been an increased concern, given the need for cannulation of the bile duct for successful transpapillary gallbladder drainage and stenting to occur. Given the burden of potentially severe adverse events, ETGBD should be reserved for patients who are otherwise not candidates for standard percutaneous drainage. Such therapies should also be performed in centers with high expertise and specifically when other biliary interventions are called for, such as in the case of concomitant choledocholithiasis.

Based on our results, recurrent cholecystitis occurred in about 1% of patients undergoing transpapillary drainage and stenting. These patients with recurrence may require repeat transpapillary drainage, or other methods of gallbladder drainage. A subset of patients can eventually undergo definitive cholecystectomy when clinically stabilized. A particular benefit of ETGBD over other endoscopic interventions such as EUS guided stenting is the avoidance of creating a chole-duodenal or gastric fistula, which can make eventual surgical intervention difficult. Stents placed during ETGBD may be removed just prior to planned cholecystectomy.

Our study had several limitations. Most of the studies included were retrospective analysis, with only one randomized controlled trial. This could have led to selection and time bias. The exclusion of non-English studies could have also led to bias. Inclusion of these studies could have led to more randomized control trials in our analysis. Many of the studies included in the pooled analysis, included the use of nasobiliary drainage. Over the past several years, this method that has been utilized less frequently, in favor of double pigtail stents making the application of our data to everyday practice more difficult. Though based on prior subgroup analysis, double pigtail stenting was compared to nasobiliary drainage with similar rates of technical (85% vs 81%), and clinical success (95% vs 93%)[21]. Outcome definitions, including technical success and clinical success varied among the included studies. This may have confounded the pooled results, though publication bias was not significant based on indicators that were used.

In conclusion, our study supports that ETGBD is a safe and efficacious procedure for inoperable patients with cholecystitis. Given its relative technical difficulty, which is inherent to ERCP, it should be performed in high volume centers and when patients are unfit for percutaneous drainage. Its clinical success rates were comparable to prior analyses, and rates of adverse events were acceptable. At this time further data and prospective trials would be beneficial in evaluating the long-term outcomes of ETGBD.

Percutaneous gallbladder drainage has been the standard treatment of acute cholecystitis in patients who are not surgical candidates. Our study sought to evaluate the efficacy and safety of transpapillary drainage for acute cholecystitis in this subset of patients.

The key topics of interest include non-surgical, less-invasive techniques to treat acute cholecystitis. The evolution of safe and effective treatments in acute cholecystitis can lead to improved patient outcomes and quality of life following treatment. Future research can also have a positive effect on cost effectiveness and health care utilization.

The main objectives were to evaluate feasibility, efficacy and safety of transpapillary gallbladder drainage in inoperable patients for the treatment of acute cholecystitis. This can positively affect further research and direct comparison trials.

A systematic review was performed followed by updated meta-analysis.

The pooled technical success rate of endoscopic transpapillary gallbladder drainage (ETGBD) was 82.62% [95% confidence interval (CI): 80.63-84.52]. The pooled clinical success rate was found to be 94.87% (95%CI: 93.54-96.05). The pooled overall complication rate was 8.83% (95%CI: 7.42-10.34). Pooled rates of post procedure adverse events were bleeding 1.03% (95%CI: 0.58-1.62), perforation 0.78% (95%CI: 0.39-1.29), peritonitis/bile leak 0.45% (95%CI: 0.17-0.87), and pancreatitis 1.98% (95%CI: 1.33-2.76). The pooled rates of stent occlusion and migration were 0.39% (95%CI: 0.13-0.78) and 1.3% (95%CI: 0.75-1.99) respectively. The pooled rate of cholecystitis recurrence following ETGBD was 1.48% (95%CI: 0.92-2.16).

Our results demonstrated that transpapillary gallbladder drainage for treatment of acute cholecystitis is both an efficacious and safe procedure in patients that are inoperable. This particular method of gallbladder drainage may offer an alternative to a certain subset of inoperable patients who are otherwise not candidates for percutaneous drainage. Patients who demonstrate signs of concomitant choledocholithiasis or cholangitis also benefit. Comparison between percutaneous drainage, and endoscopic drainage methods with endoscopic ultrasound or a transpapillary approach has been explored however results remain inconclusive.

Future research should involve randomized controlled trials to compare the different non-surgical techniques used in treatment of acute cholecystitis. In regards to ETGBD, emphasis should be placed on different stenting methods, along with assessment of long term outcomes.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Corresponding Author's Membership in Professional Societies: American College of Gastroenterology, No. 48589; American Gastroenterological Association, No. 1325879; American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy, No. 164312; and American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases.

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: United States

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Martínez-Pérez A, Sekine K S-Editor: Gao CC L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Li JH

| 1. | Everhart JE, Khare M, Hill M, Maurer KR. Prevalence and ethnic differences in gallbladder disease in the United States. Gastroenterology. 1999;117:632-639. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 549] [Cited by in RCA: 539] [Article Influence: 20.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Friedman GD. Natural history of asymptomatic and symptomatic gallstones. Am J Surg. 1993;165:399-404. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 261] [Cited by in RCA: 251] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Winbladh A, Gullstrand P, Svanvik J, Sandström P. Systematic review of cholecystostomy as a treatment option in acute cholecystitis. HPB (Oxford). 2009;11:183-193. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 222] [Cited by in RCA: 247] [Article Influence: 15.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 4. | Kiviniemi H, Mäkelä JT, Autio R, Tikkakoski T, Leinonen S, Siniluoto T, Perälä J, Päivänsalo M, Merikanto J. Percutaneous cholecystostomy in acute cholecystitis in high-risk patients: an analysis of 69 patients. Int Surg. 1998;83:299-302. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Lee MJ, Saini S, Brink JA, Hahn PF, Simeone JF, Morrison MC, Rattner D, Mueller PR. Treatment of critically ill patients with sepsis of unknown cause: value of percutaneous cholecystostomy. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1991;156:1163-1166. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Itoi T, Sofuni A, Itokawa F, Tsuchiya T, Kurihara T, Ishii K, Tsuji S, Ikeuchi N, Tsukamoto S, Takeuchi M, Kawai T, Moriyasu F. Endoscopic transpapillary gallbladder drainage in patients with acute cholecystitis in whom percutaneous transhepatic approach is contraindicated or anatomically impossible (with video). Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;68:455-460. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 102] [Cited by in RCA: 118] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Kim TH, Park DE, Chon HK. Endoscopic transpapillary gallbladder drainage for the management of acute calculus cholecystitis patients unfit for urgent cholecystectomy. PLoS One. 2020;15:e0240219. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Doi S, Yasuda I, Mabuchi M, Iwata K, Ando N, Iwashita T, Uemura S, Okuno M, Mukai T, Adachi S, Taniguchi K. Hybrid procedure combining endoscopic gallbladder lavage and internal drainage with elective cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis: A prospective pilot study (The BLADE study). Dig Endosc. 2018;30:501-507. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Sagami R, Hayasaka K, Ujihara T, Nakahara R, Murakami D, Iwaki T, Suehiro S, Katsuyama Y, Harada H, Nishikiori H, Murakami K, Amano Y. Endoscopic transpapillary gallbladder drainage for acute cholecystitis is feasible for patients receiving antithrombotic therapy. Dig Endosc. 2020;32:1092-1099. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Sanjay P, Mittapalli D, Marioud A, White RD, Ram R, Alijani A. Clinical outcomes of a percutaneous cholecystostomy for acute cholecystitis: a multicentre analysis. HPB (Oxford). 2013;15:511-516. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in RCA: 107] [Article Influence: 8.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | McGillicuddy EA, Schuster KM, Barre K, Suarez L, Hall MR, Kaml GJ, Davis KA, Longo WE. Non-operative management of acute cholecystitis in the elderly. Br J Surg. 2012;99:1254-1261. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | de la Serna-Higuera C, Pérez-Miranda M, Gil-Simón P, Ruiz-Zorrilla R, Diez-Redondo P, Alcaide N, Sancho-del Val L, Nuñez-Rodriguez H. EUS-guided transenteric gallbladder drainage with a new fistula-forming, lumen-apposing metal stent. Gastrointest Endosc. 2013;77:303-308. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 89] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Walter D, Teoh AY, Itoi T, Pérez-Miranda M, Larghi A, Sanchez-Yague A, Siersema PD, Vleggaar FP. EUS-guided gall bladder drainage with a lumen-apposing metal stent: a prospective long-term evaluation. Gut. 2016;65:6-8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 155] [Cited by in RCA: 146] [Article Influence: 16.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Stuart A, Ord JK. Kendall’s Advanced Theory of Statistics. 6th ed. London: Edward Arnold, 1994. |

| 15. | DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7:177-188. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26739] [Cited by in RCA: 30428] [Article Influence: 780.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Harbord RM, Egger M, Sterne JA. A modified test for small-study effects in meta-analyses of controlled trials with binary endpoints. Stat Med. 2006;25:3443-3457. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1463] [Cited by in RCA: 1705] [Article Influence: 89.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Sterne JA, Egger M, Smith GD. Systematic reviews in health care: Investigating and dealing with publication and other biases in meta-analysis. BMJ. 2001;323:101-105. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1519] [Cited by in RCA: 1572] [Article Influence: 65.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Sterne JA, Egger M. Funnel plots for detecting bias in meta-analysis: guidelines on choice of axis. J Clin Epidemiol. 2001;54:1046-1055. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2183] [Cited by in RCA: 2643] [Article Influence: 110.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Mori Y, Itoi T, Baron TH, Takada T, Strasberg SM, Pitt HA, Ukai T, Shikata S, Noguchi Y, Teoh AYB, Kim MH, Asbun HJ, Endo I, Yokoe M, Miura F, Okamoto K, Suzuki K, Umezawa A, Iwashita Y, Hibi T, Wakabayashi G, Han HS, Yoon YS, Choi IS, Hwang TL, Chen MF, Garden OJ, Singh H, Liau KH, Huang WS, Gouma DJ, Belli G, Dervenis C, de Santibañes E, Giménez ME, Windsor JA, Lau WY, Cherqui D, Jagannath P, Supe AN, Liu KH, Su CH, Deziel DJ, Chen XP, Fan ST, Ker CG, Jonas E, Padbury R, Mukai S, Honda G, Sugioka A, Asai K, Higuchi R, Wada K, Yoshida M, Mayumi T, Hirata K, Sumiyama Y, Inui K, Yamamoto M. Tokyo Guidelines 2018: management strategies for gallbladder drainage in patients with acute cholecystitis (with videos). J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2018;25:87-95. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 225] [Cited by in RCA: 211] [Article Influence: 30.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Kjaer DW, Kruse A, Funch-Jensen P. Endoscopic gallbladder drainage of patients with acute cholecystitis. Endoscopy. 2007;39:304-308. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 21. | Khan MA, Atiq O, Kubiliun N, Ali B, Kamal F, Nollan R, Ismail MK, Tombazzi C, Kahaleh M, Baron TH. Efficacy and safety of endoscopic gallbladder drainage in acute cholecystitis: Is it better than percutaneous gallbladder drainage? Gastrointest Endosc. 2017;85:76-87.e3. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 11.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Higa JT, Sahar N, Kozarek RA, La Selva D, Larsen MC, Gan SI, Ross AS, Irani SS. EUS-guided gallbladder drainage with a lumen-apposing metal stent vs endoscopic transpapillary gallbladder drainage for the treatment of acute cholecystitis (with videos). Gastrointest Endosc. 2019;90:483-492. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Lyu Y, Li T, Wang B, Cheng Y, Chen L, Zhao S. Comparison of Three Methods of Gallbladder Drainage for Patients with Acute Cholecystitis Who Are at High Surgical Risk: A Network Meta-Analysis and Systematic Review. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2021;. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Storm AC, Vargas EJ, Chin JY, Chandrasekhara V, Abu Dayyeh BK, Levy MJ, Martin JA, Topazian MD, Andrews JC, Schiller HJ, Kamath PS, Petersen BT. Transpapillary gallbladder stent placement for long-term therapy of acute cholecystitis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2021;. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Hayes D, Lucas G, Discolo A, French B, Wells S. Endoscopic transpapillary stenting for the management of acute cholecystitis. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2020;405:191-198. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Nakahara K, Morita R, Michikawa Y, Suetani K, Morita N, Fujita A, Sato J, Igarashi Y, Ikeda H, Matsunaga K, Watanabe T, Kobayashi S, Otsubo T, Itoh F. Endoscopic Transpapillary Gallbladder Drainage for Acute Cholecystitis After Biliary Self-Expandable Metal Stent Placement. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2020;30:416-423. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Oh D, Song TJ, Cho DH, Park DH, Seo DW, Lee SK, Kim MH, Lee SS. EUS-guided cholecystostomy vs endoscopic transpapillary cholecystostomy for acute cholecystitis in high-risk surgical patients. Gastrointest Endosc. 2019;89:289-298. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 12.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Iino C, Shimoyama T, Igarashi T, Aihara T, Ishii K, Sakamoto J, Tono H, Fukuda S. Comparable efficacy of endoscopic transpapillary gallbladder drainage and percutaneous transhepatic gallbladder drainage in acute cholecystitis. Endosc Int Open. 2018;6:E594-E601. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Itoi T, Takada T, Hwang TL, Endo I, Akazawa K, Miura F, Chen MF, Jan YY, Ker CG, Wang HP, Gomi H, Yokoe M, Kiriyama S, Wada K, Yamaue H, Miyazaki M, Yamamoto M. Percutaneous and endoscopic gallbladder drainage for acute cholecystitis: international multicenter comparative study using propensity score-matched analysis. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2017;24:362-368. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Yang MJ, Yoo BM, Kim JH, Hwang JC, Baek NH, Kim SS, Lim SG, Shin SJ, Cheong JY, Lee KM, Lee KJ, Kim WH, Cho SW. Endoscopic naso-gallbladder drainage vs gallbladder stenting before cholecystectomy in patients with acute cholecystitis and a high suspicion of choledocholithiasis: a prospective randomised preliminary study. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2016;51:472-478. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Inoue T, Okumura F, Kachi K, Fukusada S, Iwasaki H, Ozeki T, Suzuki Y, Anbe K, Nishie H, Mizushima T, Sano H. Long-term outcomes of endoscopic gallbladder stenting in high-risk surgical patients with calculous cholecystitis (with videos). Gastrointest Endosc. 2016;83:905-913. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | McCarthy ST, Tujios S, Fontana RJ, Rahnama-Moghadam S, Elmunzer BJ, Kwon RS, Wamsteker EJ, Anderson MA, Scheiman JM, Elta GH, Piraka CR. Endoscopic Transpapillary Gallbladder Stent Placement Is Safe and Effective in High-Risk Patients Without Cirrhosis. Dig Dis Sci. 2015;60:2516-2522. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Widmer J, Alvarez P, Sharaiha RZ, Gossain S, Kedia P, Sarkaria S, Sethi A, Turner BG, Millman J, Lieberman M, Nandakumar G, Umrania H, Gaidhane M, Kahaleh M. Endoscopic Gallbladder Drainage for Acute Cholecystitis. Clin Endosc. 2015;48:411-420. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Itoi T, Kawakami H, Katanuma A, Irisawa A, Sofuni A, Itokawa F, Tsuchiya T, Tanaka R, Umeda J, Ryozawa S, Doi S, Sakamoto N, Yasuda I. Endoscopic nasogallbladder tube or stent placement in acute cholecystitis: a preliminary prospective randomized trial in Japan (with videos). Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;81:111-118. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Maekawa S, Nomura R, Murase T, Ann Y, Oeholm M, Harada M. Endoscopic gallbladder stenting for acute cholecystitis: a retrospective study of 46 elderly patients aged 65 years or older. BMC Gastroenterol. 2013;13:65. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Lee TH, Park DH, Lee SS, Seo DW, Park SH, Lee SK, Kim MH, Kim SJ. Outcomes of endoscopic transpapillary gallbladder stenting for symptomatic gallbladder diseases: a multicenter prospective follow-up study. Endoscopy. 2011;43:702-708. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Mutignani M, Iacopini F, Perri V, Familiari P, Tringali A, Spada C, Ingrosso M, Costamagna G. Endoscopic gallbladder drainage for acute cholecystitis: technical and clinical results. Endoscopy. 2009;41:539-546. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Pannala R, Petersen BT, Gostout CJ, Topazian MD, Levy MJ, Baron TH. Endoscopic transpapillary gallbladder drainage: 10-year single center experience. Minerva Gastroenterol Dietol. 2008;54:107-113. [PubMed] |

| 39. | Schlenker C, Trotter JF, Shah RJ, Everson G, Chen YK, Antillon D, Antillon MR. Endoscopic gallbladder stent placement for treatment of symptomatic cholelithiasis in patients with end-stage liver disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:278-283. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Tamada K, Seki H, Sato K, Kano T, Sugiyama S, Ichiyama M, Wada S, Ohashi A, Tomiyama G, Ueno A. Efficacy of endoscopic retrograde cholecystoendoprosthesis (ERCCE) for cholecystitis. Endoscopy. 1991;23:2-3. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |