ENDOSCOPIC MANAGEMENT FOR DIFFICULT CBD STONE

Endoscopic mechanical lithotripsy

First introduced in 1982, mechanical lithotripsy has been commonly used for fragmentation of the stone. High success rate (79%-96%) of mechanical lithotripsy for CBD stone larger than 2 cm has been demonstrated due to high breaking strength of contemporary lithotripter baskets[1,7]. Moreover, the procedure is widely available, cost-effective, and simple. In general, there are two types of mechanical lithotripters, depending on elective or salvage therapeutic goal. The basket for elective model (‘through-the-scope’ model) consists of the basket, inner plastic sheath, and outer metal sheath. Fragmentation of the stones can also be performed after removing the duodenoscope from the patient and removing the handle from the basket. Additionally, basket impaction can also happen with this type of scope (less frequent compared to extraction baskets with thinner wires and weaker handles). The basket intended for salvage therapy is a type in which a traditional basket is used to crush a stone impacted in the bile duct[1,3].

However, higher failure rate has been observed in patients with stones larger than 2 cm in diameter[3,8]. A retrospective cohort study in 162 subjects showed significantly lower cumulative probability of bile duct clearance (P < 0.02) in clearance of stones larger than 2.8 cm in diameter[7,8]. A study in 102 subjects demonstrated stones larger than 30 mm [odds ratio (OR) = 4.32], impacted (OR = 17.8), and ratio of bile duct diameter larger than 1 (OR = 5.47) as the predictors for failure in doing mechanical lithotripsy[9]. Another study added another predictive factor for mechanical lithotripsy, which was the impacted stone in the bile duct due to inability of the basket to grasp the stone properly or to pass the basket proximally towards the stone[10]. Stones with harder consistency have also been associated with higher failure rates and may not be easily managed by the lithotripter basket[11]. However, there was a contradictory evidence from a single center study in 592 subjects, which showed high clearance rates for impacted stones (96%) and stones larger than 2 cm in diameter (96%)[12].

Lack of preferences in using mechanical lithotripsy is also due to its potential complications. Common technical and medical complications issue which might occur, such as basket impaction, fracture of the basket wire, broken handle, bleeding, pancreatitis, perforation or injury to the bile duct, and cholangitis, particularly in patients with larger stones[1,12]. However, a multi-center study indicated lower rate of complications associated with mechanical lithotripsy (3.6%)[13]. When complications occur, non-surgical interventions are sometimes necessary, for instance, extended sphincterotomy, use another lithotripter, shift towards other procedures (e.g., electrohydraulic lithotripsy, EHL), or spontaneous passage of impacted stones or basket[1].

EHL

As an option in managing difficult bile duct stones, EHL was initially used as an industrial tool for disintegrating stones in mines. The first attempt of using this technique in biliary stone was performed by Koch et al[14]. The device contains a bipolar lithotripsy probe and a charge generator with an aqueous medium. The principal mechanism of EHL is a production of high-frequency hydraulic pressure waves, which is subsequently absorbed by bile duct stones. The procedure can be done by inserting a cholangioscope through the instrument channel of another scope with continuous water irrigation under the guidance of fluoroscopy. The water acts as a propagator of shock waves and as a fluid medium which can flush away the debris, and therefore providing clearer visualization of the stones and ductal wall[15]. This mechanism, however, can lead to several adverse events, such as unintended perforation of the bile duct wall (related to the inappropriate probe positioning) or poor direct visualization by fluoroscopic guidance since it only utilizes two-dimensional imaging[16].

EHL has been proposed as one of the best methods for disintegration of biliary stones due to its compact and relatively cost-effective equipment. In addition, the procedure does not require supplementary protective gear or specialized trainings[1]. Recently, a study by Kamiyama et al[17] established a clinical evidence of technical feasibility and clinical effectiveness from utilizing EHL with a digital single-operator cholangioscope (SPY-DS). In this pilot study, complete stone clearance rate achieved was 97% in 42 subjects who underwent EHL with SPY-DS[17]. Another study by Binmoeller et al[18] also showed successful results of EHL in 63 of 64 subjects with history of failed mechanical lithotripsy. High rates of stone disintegration (96%) and stone clearance (90%) were also demonstrated by Arya et al[19].

It has also been demonstrated that it is possible using EHL technique under ERCP or per-oral transluminal cholangioscopy (PTLC) guidance. Several indications for performing EHL under ERCP guidance are large or multiple bile duct stones, intrahepatic bile duct stones, assemblage of multiple stones, and bile duct stricture. The technique involves insertion of a duodenoscope into the ampulla of Vater and inserting an ERCP catheter into the CBD simultaneously. The high frequency shockwaves are applied as a continuous discharge, generated using an electrohydraulic shock wave generator. Removal of bile duct stones is conducted with basket or balloon catheter. On the other hand, EHL under PTLC guidance is usually performed in the case of surgically altered anatomy or duodenal obstruction, where the papilla becomes inaccessible for ERCP to be performed. EHL under PTLC guidance can also be performed on a large stone, which cannot be removed by basket or balloon catheter. The mechanism consists of creating a fistula between biliary tract and stomach, through which EHL will be performed. Before performing PTLC, the operator needs to perform an endoscopic ultrasound-guided hepaticogastrostomy (EUS-HGS) first for placing the stent from the intrahepatic bile duct to the stomach. Detection of intrahepatic bile duct is done by inserting an echoendoscope into the stomach. For small CBD stones, a balloon catheter can be used to perform antegrade stone extraction, while in larger CBD stones, stone fragmentation is necessary by performing antegrade stone extraction through EHL with SPY-DS. EUS-HGS stent is particularly beneficial for performing stone extraction in extremely small stones after EHL[17].

Overall, the rate of complications in EHL is relatively low (approximately 7%-9%). The most common complications are cholangitis, ductal perforation or injury, and hemobilia[1]. A retrospective study showed higher success rate (80%) with lower rate of complications (7.7%) in subjects with history of failed conventional attempts who underwent EHL and further ERCPs, compared to stenting as a single procedure. These data also included elderly and frail population[20]. In a study by Kamiyama et al[17], adverse events (cholangitis and acute pancreatitis) were observed in approximately 14% of the subjects. Nevertheless, the complications were able to be treated conservatively in the study.

Extracorporeal shockwave lithotripsy

The basic principle of extracorporeal shockwave lithotripsy (ESWL) is the generation of high-pressure electrohydraulic shockwaves outside the body. The waves are produced by piezoelectric crystals of electromagnetic membrane technology and directed by elliptical transducers through a liquid medium. This procedure is conducted under the guidance of ultrasound machine or fluoroscopy. Sometimes, a nasobiliary tube (NBT) can also be inserted for better visualization. The success of single session of ESWL procedure is critically determined by the size and structure of the stones, as well as the presence of bile duct stenosis. Moreover, ESWL allows fragmentation of multiple stones simultaneously[1].

High success rate of ESWL procedure has been established from previous studies. A study by Sauerbruch and Stern[21] demonstrated high efficacy of CBD stones fragmentation (approximately 90%) with minimal adverse events. A single-center study in 214 subjects who underwent ESWL throughout 15 years of observation also showed high complete stone clearance (89.7%). Around 57% of the subjects with clearance had biliary stones smaller than 2 cm (0.8-5 cm) in diameter, while 51% of the subjects without clearance had biliary stones larger than 2 cm (1-3.5 cm) in diameter[22]. Similar finding was also found by Tandan and Reddy[23], showing complete clearance of the large CBD stones (84.4%) with over 75% of the subjects only needed three or fewer ESWL sessions (delivering 5000 shocks per session). Generally, ESWL also showed minimal and mild adverse events, although more serious adverse events, such as transient biliary colic, subcutaneous ecchymosis, cardiac arrhythmia, haemobilia (often self-limiting), cholangitis, ileus, pancreatitis, perirenal hematoma, bowel perforation, splenic rupture, lung trauma, and necrotizing pancreatitis also need to be anticipated[1,23]. In addition, considerably low recurrence rate of CBD stones after CBD clearance has also been indicated from previous studies (roughly, 14% of recurrence rate)[24,25].

ESWL can also be particularly beneficial for patients with anatomically abnormal structures. For instance, in patients with inaccessible papilla due to history of Billroth-II or Roux-en-Y surgeries. Also, in cases with surgically altered anatomy, not only the size of bile duct stones, but also the size of CBD itself is often large. In these cases, endoscopic nasobiliary drainage tube placement is often required to guide ESWL. If optimal result cannot be achieved with ESWL, then percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage (PTBD) or endoscopic ultrasound (EUS)-guided intraductal lithotripsy can be performed[1,26].

Laser lithotripsy

First introduced in 1986, the general concept of laser lithotripsy (LL) includes laser light at a certain wavelength, directed towards the surface of the stone. This process induces a generation of wave-mediated disintegration of stone[1]. The first type of laser utilized for bile duct stones is pulsed laser, followed by neodymium-doped yttrium aluminium garnet (Nd:YAG), coumarin, rhodamine, and the new Frequency Doubled Double Pulse Nd:YAG (FREDDY) system[1,27]. LL can be conducted by transhepatic approach or under direct visualization using cholangioscopic or fluoroscopic guidance[1]. The use of cholangioscopic guidance has been widely accepted as more superior compared to fluoroscopic guidance, especially with the emerging single-operator cholangioscopy-guided system. In a prospective multicenter clinical study, 94.1% of the patients successfully underwent complete stone clearance after one session with cholangioscopy-guided LL and/or EHL procedures[28]. The main concern of using this approach is lower quality of fiber optic image compared to the quality of videocholangioscopes[1].

Although the range of success rate is quite wide compared to other modalities (64%-97%), previous evidence have pointed out the superiority of LL in stone clearance rate and faster duration of treatment and stone fragmentation, therefore, also contributing to its cost-effectiveness[1]. A randomized study by Neuhaus et al[29] showed significantly higher success rate (P < 0.05) of bile duct clearance achieved by LL (97%) compared to ESWL (73%). This study involved 60 subjects with history of previous failed standard stone extraction. The study also indicated significantly shorter duration of treatment (0.9 ± 2.3 d in LL vs 3.9 ± 3.5 d in ESWL, P < 0.001) and a smaller number of sessions (1.2 ± 0.4 in LL vs 3.0 ± 1.3 in ESWL, P < 0.001)[29]. Another prospective randomized study by Jakobs et al[30] also reinstated the superiority of LL compared to ESWL, in terms of complete stone fragmentation percentages (82.4% vs 52.4%). Groups treated with LL also demonstrated significantly lower number of fragmentation sessions (P = 0.0001) and additional endoscopic sessions (P = 0.002)[30].

Recent evidence related to LL mentioned an innovation in the procedural aspect, as well as the possibility of this method to reduce the necessity for post-procedure surgery. A randomized trial by Buxbaum et al[31] was comparing the use of cholangioscopy-guided LL and conventional therapy in 60 subjects with bile duct stones larger than 1 cm in diameter. In this study, conventional therapies, such as mechanical lithotripsy and papillary dilation were included in the laser group. Successful endoscopic stone clearance was shown in 93% of the subjects who underwent cholangioscopy, compared to only 67% in patients who underwent only conventional approaches (P = 0.009). However, the mean duration of procedure was significantly longer in cholangioscopy-guided LL group (120.7 ± 40.2 min) compared to conventional therapy group (82.1 ± 49.3 min, P = 0.0008)[31]. The use of double-lumen basket has also been introduced from a case series for providing LL with higher effectiveness by allowing a passage of a laser probe after the stone is caught by the basket[32].

Direct peroral cholangioscopy

A direct observation with direct peroral cholangioscopy (DPOC) utilizes a high-definition ultra-slim upper endoscope with narrow band imaging capability through the biliary sphincter into the bile duct. Gradually, with this technique, DPOC becomes a preferable method for managing bile duct stones due to its therapeutic potentials, digital image quality, and the capability to be performed with a single operator. Aside from high-resolution optics, DOPC also has 2.00 mm working channel which can be helpful in the intervention for malignant strictures of impacted bile duct stones with additional accessories which cannot pass through other cholangioscopes[1,3].

The role of additional accessories or techniques has been regarded as important in DPOC, especially for increasing the success rate of DPOC. A major challenge of using an ultra-slim endoscope is the looping of endoscope in the stomach or duodenum due to the difficulty of directing its flexible shaft from the duodenum into the biliary tract. A study by Moon et al[33] demonstrated a utilization of intraductal balloon in ropeway technique. This balloon is attached in an intrahepatic bile duct to facilitate the ultra-slim upper endoscope into the biliary tree. The authors, however, mentioned the presence of technical problems for maintaining the position of the endoscope when the balloon was withdrawn[33]. Aside from intra-ductal balloon, the use of an over tube balloon has also been proposed to assist the advancement of ultra-slim upper endoscope. However, this method is not very recommended due to discomfort for patient and possibility of looping as a result of larger inner diameter of the over tube (10.8 mm), compared to the outer diameter of the upper endoscope (5.2-6 mm)[34,35]. Another approach is by inserting upper endoscope assisted with a guidewire, which is placed during ERCP. However, there is also a possibility of dislodged guidewire and looping with this method. In some cases, applying manual pressure on the abdomen of the patient has been shown to allow wider passage of the upper endoscope into the hilar area[35,36]. A small study conducted in 18 patients with prior failed attempt of conventional therapy demonstrated a favorable result of DPOC-guided EHL and LL, showing almost 90% of success rate with average of 1.6 endoscopic sessions for every patient[37].

Despite its effectiveness, DPOC has been associated with a handful of adverse events. One of the most serious complications is air embolism, which manifests from asymptomatic to hypoxia, cardiac arrest, or even severe cerebral ischemia[3]. One case report presented an occurrence of left-sided hemiparesis after the application of direct cholangioscopy with intraductal balloon anchoring system[38]. Several ways have been advised to anticipate this problem, such as using saline irrigation or copious water, and using CO2 for insufflation[3,39].

Endoscopic papillary large balloon dilation

Endoscopic papillary large balloon dilation (EPLBD), or also known as dilatation-assisted stone extraction (DASE), was first reported by Ersoz et al[40], who utilized an esophageal dilatation balloon with 12-20 mm in diameter. The stone extraction in this procedure is performed after partial biliary sphincterotomy and dilation of papillary orifice. Initial studies demonstrated promising success rates (88%-100%) with acceptable and self-limited complication rates (0%-16%) from this procedure[1]. A study consisting of two prospective trials from 2014 to 2019 also exhibited similarly high success rates (91.3%) in 299 subjects with difficult bile duct stones (defined as larger than 1 cm in diameter, impacted, or multiple stones) with low rate of complications (10.8%). No hospital mortality was observed among 46 subjects who underwent EPLBD after prior failed attempt of conventional approaches[41].

Divided opinions still arise pertaining to the relationship between EPLBD and EST, especially related to whether EPLBD should be first preceded by EST or not. One meta-analysis comparing EPLBD and EST showed similar rates of complete stone removal between both techniques (95% vs 96%, P = 0.36). However, the use of EPLBD was associated with lower number of hemorrhages, compared to EST (0.1% vs 4.2%, P < 0.00001). Higher utilization of endoscopic mechanical lithotripsy was also found in EPLBD group (35% in EPLBD vs 26.2% in EST, P = 0.0004)[42]. Another problem is the high incidence of pancreatitis in cases of EPLBD without a prior EST, which possibly due to the injury of pancreatic sphincter caused by the balloon. Meanwhile, the risk of bleeding or retroduodenal perforation is also higher in large EST. There is insufficient evidence regarding the efficacy of EPLBD without EST, particularly in managing large bile duct stones. Nevertheless, theoretically, a large balloon dilatation can be implemented safely by making a small EST to detach the pancreatic orifice from biliary opening, while minimizing the risk of pancreatitis, bleeding, or perforation[3]. A study in 60 subjects with full length EST performed before EPLBD for large CBD stones (average size of 16 mm) showed high success rate of complete stone clearance in a single session procedure[43]. In the meantime, there were also studies showing high stone removal rates using balloon dilatation without EST (95%-98%) with around 1-1.2 mean endoscopic session per patient[44,45].

As implied above, despite being a promising therapeutic option, EPLBD is also associated with serious complications. Higher risk of post-ERCP pancreatitis is associated with compressed pancreatic duct, which can be caused by intra-mucosal bleeding, inflammation of the papilla, and abnormally loose sphincter of Oddi[46]. A large multi-center study showed approximately 6% of 946 subjects experienced bleeding after EPLBD procedure. From the multivariate analysis, there are three factors which may influence the hemorrhage risk, i.e., the presence of cirrhosis (OR = 8, P = 0.003), full-length EST (OR = 6.22, P < 0.001), and stones ≥ 16 mm (OR = 4, P < 0.001)[47]. However, another study pointed out only a small number of self-limited bleeding complications (around 8%) in EPLBD procedure preceded with full-length EST[43]. One randomized controlled trial proposed longer duration of dilatation (5 min vs 1 min) to increase the adequacy of the loose sphincter of Oddi, thus, also reducing the risk of post-ERCP pancreatitis[48].

EPLBD has also become an alluring option for patients with surgically altered anatomy, where sphincterotomy cannot be performed adequately. A retrospective study with EPLBD or combination between EPLBD and EST performed in 30 subjects with previous history of Billroth-II gastrectomy, demonstrated 96.7% successful stone removal rate and successful stone retrieval during the first session in 90% of the subjects. One subject underwent further surgery after the procedure due to severe CBD stricture, while two subjects underwent mechanical lithotripsy afterwards[49]. One systematic review also supported the positive findings of EPLBD in surgically altered anatomy cases, exhibiting technical success rate ranging between 89%-100% and rate of complete clearance in one session ranging between 96.7%-100%[26].

Endoscopic biliary stenting

Endoscopic biliary stenting has been proposed as a useful alternative approach for patients with difficult bile duct stones and high risk of complications (i.e., elderly, patients with serious comorbidities, patients on anti-thrombotic, or patients who are frail). This method can also be a definitive therapy for those who cannot undergo surgical approach[1,3]. A study in 201 subjects who underwent plastic biliary stenting and could not undergo repeated ERCP for stone extraction demonstrated exceptional median stent patency of almost five years with low number of complications (7.4% of the subjects suffered from cholangitis)[50]. The application of fully covered self-expandable metal stents (FCSEMs) has also become more popular these days. In a large retrospective study involving 44 subjects with difficult bile duct stones and history of incomplete stone clearance, 82% of the subjects had complete stone clearance using FCSEMs[51].

In general, there is no detailed mechanism yet on how biliary stents can contribute towards stone removal. It has been indicated that stone fragmentation may be caused by mechanical friction against the stones. A study has supported this theory by showing 60% of decrease in the size of bile duct stones within 1-2 years after biliary stenting was performed[1,52]. A study in 28 geriatric subjects who were unresponsive towards endoscopic approaches displayed a significant decrease in the size of bile duct stones within six months after endoscopic biliary stenting. This procedure, however, was also combined by oral consumption of ursodeoxycholic acid and terpene therapy[53]. A single study performed in a tertiary center also highlighted the benefit of performing endoscopic biliary stenting. In approximately 208 subjects with difficult stones, the diameter of the largest stone appeared to be reduced significantly after periodic endoscopic biliary stenting was performed (17.41 ± 7.44 mm vs 15.85 ± 7.73 mm, P < 0.001). In further multivariate analysis, CBD diameter (OR = 0.78, P = 0.001) and the diameter of the largest stone (OR = 0.808, P = 0.001) were considered as significant independent risk factors to success rate[4].

EUS-guided stone extraction

In recent years, the application of EUS in therapeutic interventions of hepatopancreatobiliary problems has been emerging steadily. Previously, removal of CBD stones under solely EUS guidance has been proposed to minimize the use of fluoroscopy and contrast medium injection. Artifon et al[54] demonstrated the feasibility of adapting this strategy by showing a comparable EUS-guided successful cannulation of the bile duct with ERCP cannulation. This strategy, though, was performed by an endosonographer with high expertise in both EUS and ERCP. Altogether, EUS-guided technique is preferable in conditions of previous failed biliary cannulation attempts or difficulty in accessing the papilla (e.g., malignant duodenal obstruction, altered surgical anatomy, large duodenal diverticulum)[3].

EUS-guided stone extraction consists of several steps. Initially, the biliary system needs to be punctured under EUS guidance from the stomach or from any location where dilated left intrahepatic duct can be accessed easier from the duodenal bulb. A wire will then be passed through the FNA needle into the duodenum (can be performed under fluoroscopy guidance). This procedure can be performed with a balloon-pushed antegrade (EUS-AG) (when the papilla cannot be accessed) or with rendezvous technique (EUS-RV) (when the papilla is accessible). Consequently, the stone will be pushed with a retrieval balloon[3,55].

Previous studies have evaluated the outcome of performing EUS-guided stone extraction. A multicenter retrospective study demonstrated 72% of technical success rate and 17% of complication rate. In this study, technical issue occurred due to failure in making a puncture on the intra-hepatic bile duct[56]. Other possible technical problems, which may need to be considered, are guidewire passage and stone extraction through the ampulla. Application of EPLBD can also overcome the problem of large distal CBD to increase the possibility of complete stone removal. However, this technique is also associated with higher risk of bile leak due to utilization of multiple modalities and prolonged duration of the procedure. To minimize the risk of bile leak, EUS-HGS or EUS-hepaticojejunostomy can be performed since the first session[55].

EUS-guided approach is also propitious, especially in cases with surgically altered anatomy. A study by Weilert et al[57] in six subjects with history of Roux-en-Y gastric bypass showed 67% technical success rate with only one subject suffered from adverse event (i.e., subcapsular hematoma). Additionally, a finding by Hosmer et al[58] from a single-center study, although with smaller sample size, showed 100% success rate of EUS-HGS followed by stone extraction in nine subjects with Roux-en-Y anatomy. In 89% of the subjects, ≥ 10 mm balloon dilation of papilla was conducted[58]. Nevertheless, the technical success rate of EUS-guided management of bile duct stones in patients with surgically altered anatomy is varied widely between 60% to 100%[55]. Possible disadvantages of EUS-guided stone management in cases with surgically altered anatomy include limited approach to the left intrahepatic bile duct and risk of bile leak. Overall, in surgically altered anatomy patients, EUS-guided approach yields better results when the procedure is not performed as a single procedure, but with various therapeutic options (i.e., EUS-AG, EUS-RV, peroral cholangioscopy with intraductal lithotripsy, and EUS-guided enterobiliary fistula)[26,55].

ENDOSCOPIC APPROACH VS SURGICAL APPROACH IN MANAGING DIFFICULT BILIARY STONES

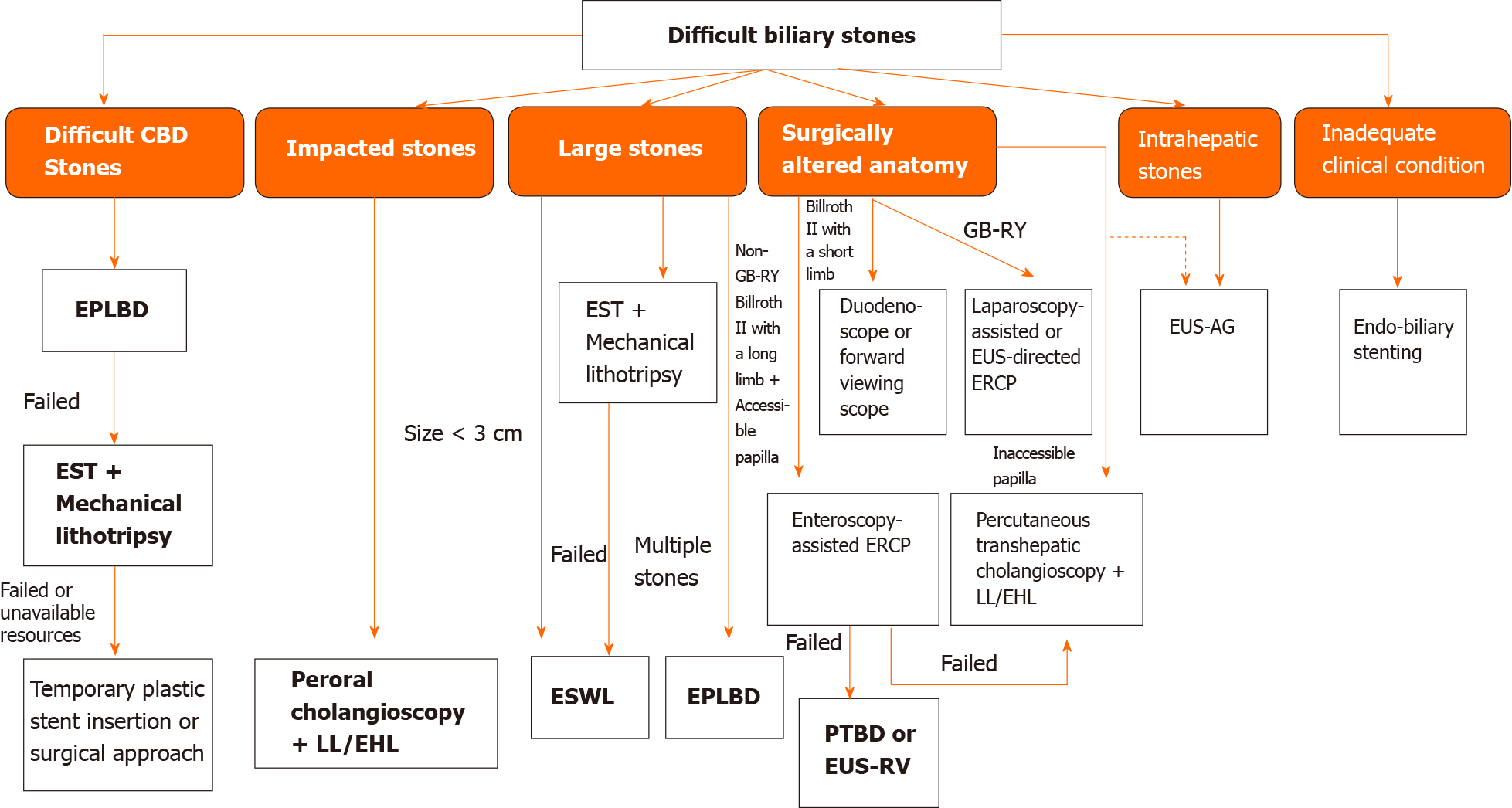

As mentioned before, management of difficult biliary stones can be considered as a complex matter. Multiple procedures or additional interventional techniques are often necessary to achieve complete stone clearance (Figure 1). Aside from endoscopic approach, surgical approach has also been proposed as one of the procedures involved in the management. The European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) defines difficult biliary stones according to the number of stones, diameter of stones (larger than 1.5 cm), unusual shapes, location, or anatomical factors. Currently, EPLBD of a previous sphincterotomy and EPLBD combined with limited sphincterotomy performed on the same session is still recommended by ESGE as the main approach in difficult CBD stones with history of failed sphincterotomy and balloon and/or basket attempts. If failed extraction is still encountered, mechanical lithotripsy, cholangioscopy-assisted lithotripsy, or ESWL can be considered. Surgical approach can be considered when the stone extraction is still failed or no available facilities to perform lithotripsy[59] (Figure 2).

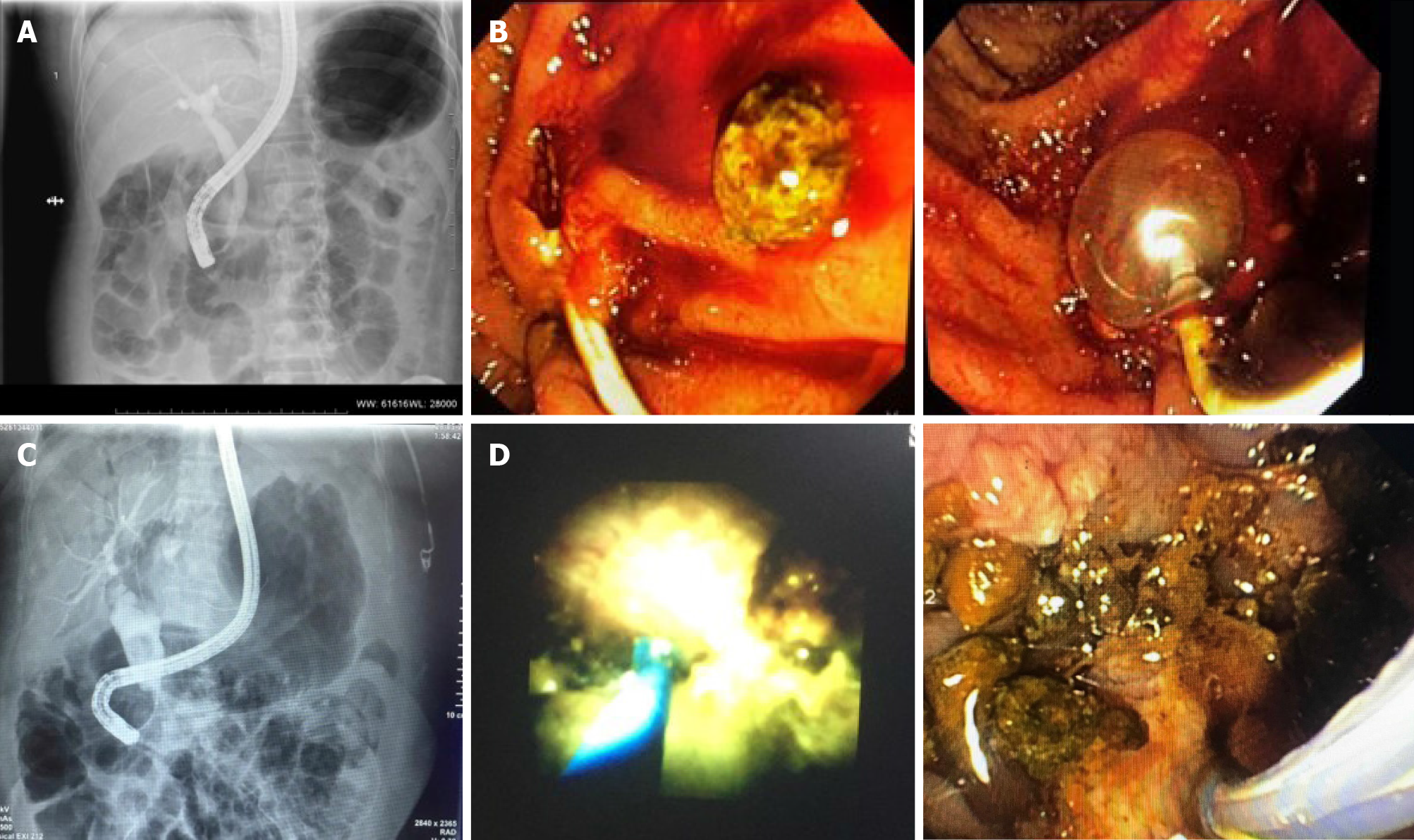

Figure 1 Multiple procedures or additional interventional techniques are often necessary to achieve complete stone clearance.

A: A cholangiography image showing dilated biliary tract with distal narrowing and impacted stone. Endoscopy unit database Medistra Hospital, Jakarta; B: Endoscopy images of impacted distal common bile duct (CBD) stone removal with balloon. Endoscopy unit database, Medistra Hospital, Jakarta; C: The cholangiography image of a patient with CBD dilatation on the proximal and large CBD stone with distal narrowing. Endoscopy unit database, Medistra Hospital, Jakarta; D: Patient underwent laser lithotripsy with Spy Glass Cholangioscopy and multiple fragmentation of stones removal. Endoscopy unit database, Medistra Hospital, Jakarta.

Figure 2 Proposed algorithm for management of difficult biliary stones[6,59,62].

CBD: Common bile duct; EPLBD: Endoscopic papillary large balloon dilation; EST: Endoscopic sphincterotomy; LL: Laser lithotripsy; EHL: Electrohydraulic lithotripsy; ESWL: Extracorporeal shockwave lithotripsy; ERCP: Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography; PTBD: Percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage; EUS-RV: Endoscopic ultrasound-rendezvous technique; EUS: Endoscopic ultrasound; EUS-AG: Endoscopic ultrasound-antegrade.

Conflicting evidence are still found from previous studies related to the comparison between endoscopic and surgical approaches. Although ESGE has suggested laparoscopic cholecystectomy, trancystic or transductal exploration of the CBD as safe and effective approaches, it has also been stated that the recommendation highly depends on the availability of facilities and local expertise[59]. A systematic review by Dasari et al[60] showed no significant difference in the mortality rates between groups treated with open surgery and groups treated with ERCP clearance. This review also favored the surgical approach by showing that groups treated with open surgery had significantly less retained stones (P = 0.0002). In addition, the authors also compared a single-stage laparoscopic procedure and two-stage endoscopic procedures. There was no significant difference in mortality and morbidity rates, as well as conversion to open surgery between both groups[60]. One meta-analysis has also shown higher success rate and significantly shorter hospital stay in one-stage laparoscopic procedure (laparoscopic CBD exploration and cholecystectomy) compared to sequential endo-laparoscopic procedures (two-stage endoscopic stone extraction followed by laparoscopic cholecystectomy). No significant differences were observed in morbidity and mortality rates, cost, as well as retained or recurrent stones. The authors, however, addressed the significant heterogeneity between studies which may reduce the validity of the analysis and the need for further studies due to the underpowered nature of most trials[61].