Published online Oct 16, 2021. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v13.i10.518

Peer-review started: May 14, 2021

First decision: July 27, 2021

Revised: August 21, 2021

Accepted: September 14, 2021

Article in press: September 14, 2021

Published online: October 16, 2021

Processing time: 152 Days and 17 Hours

Many studies evaluated magnification endoscopy (ME) to correlate changes on the gastric mucosal surface with Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection. However, few studies validated these concepts with high-definition endoscopy without ME.

To access the association between mucosal surface pattern under near focus technology and H. pylori infection status in a western population.

Cross-sectional study including all patients referred to routine upper endoscopy. Endoscopic exams were performed using standard high definition (S-HD) followed by near focus (NF-HD) examination. Presence of erythema, erosion, atrophy, and nodularity were recorded during S-HD, and surface mucosal pattern was classified using NF-HD in the gastric body. Biopsies were taken for rapid urease test and histology.

One hundred and eighty-seven patients were analyzed from August to November 2019. Of those, 47 (25.1%) were H. pylori+, and 42 (22.5%) had a previous H. pylori treatment. In the examination with S-HD, erythema had the best sensitivity for H. pylori detection (80.9%). Exudate (99.3%), nodularity (97.1%), and atrophy (95.7%) demonstrated better specificity values, but with low sensitivity (6.4%-19.1%). On the other hand, the absence of erythema was strongly associated with H. pylori- (negative predictive value = 92%). With NF-HD, 56.2% of patients presented type 1 pattern (regular arrangement of collecting venules, RAC), and only 5.7% of RAC+ patients were H. pylori+. The loss of RAC presented 87.2% sensitivity for H. pylori detection, 70.7% specificity, 50% positive predictive value, and 94.3% negative predictive value, indicating that loss of RAC was suboptimal to confirm H. pylori infection, but when RAC was seen, H. pylori infection was unlikely.

The presence of RAC at the NF-HD exam and the absence of erythema at S-HD were highly predictive of H. pylori negative status. On the other hand, the loss of RAC had a suboptimal correlation with the presence of H. pylori.

Core Tip: Imaging advances in endoscopy significantly improved our diagnostic capability. While magnification endoscopy is well incorporated in Asian countries, in Western countries most upper endoscopes devices are not equipped with this feature. In this study, we evaluated the near focus technology to access mucosal surface pattern and correlate with Helicobacter pylori infection. We believe this article will be of great interest to endoscopist in the Western, as there is still a room for better understanding gastric mucosal surface pattern and near focus technology.

- Citation: Fiuza F, Maluf-Filho F, Ide E, Furuya Jr CK, Fylyk SN, Ruas JN, Stabach L, Araujo GA, Matuguma SE, Uemura RS, Sakai CM, Yamazaki K, Ueda SS, Sakai P, Martins BC. Association between mucosal surface pattern under near focus technology and Helicobacter pylori infection. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2021; 13(10): 518-528

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v13/i10/518.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v13.i10.518

The relationship between Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection, chronic gastritis, and the development of gastric cancer is well established[1-4]. Eradication of H. pylori in patients with non-atrophic chronic gastritis could lead to regeneration of normal mucosa and interruption of Correa’s cascade[1,5,6]. In this sense, a technology that helps with diagnosis of H. pylori-associated gastritis is useful.

In recent years, many advances in endoscopic imaging have surged, allowing for better characterization of gastric mucosal patterns. High definition (HD) magnification endoscopy (ME) can increase the image view from 1.5× to 150× and allow the visualization of objects that are 10-71 μm in diameter[7]. In 2001, Yao and Oishi[8] described the characteristics of normal gastric mucosa with image magnification. In the following year, Yagi et al[9] described the differences between the magnified view of normal gastric mucosa from the pattern seen in patients with H. pylori-associated gastritis. A more detailed classification was used by Anagnostopoulos et al[10] to distinguish normal gastric mucosa, H. pylori-associated gastritis, and gastric atrophy in a Western population. Since then, several articles have studied the association between ME and histological findings[9,11,12].

However, endoscopes with magnification are scarce in Western countries. In 2016, Olympus launched the Near Focus (or Dual Focus) technology on conventional 190 endoscopes for the Western market, which consists of a variable focus lens system, allowing for close examination of the mucosa (2-6 mm) without definition loss[13].

Although there are many studies correlating the findings of ME and H. pylori status, only a few validated these findings with HD endoscopes without ME[14-18]. Moreover, most of these studies were conducted in Asian countries, in centers with high expertise with magnifying images[9,12].

The aim of this study is to access the association between mucosal surface pattern under near focus high-definition (NF-HD) technology and H. pylori infection status in a western population.

This was a cross-sectional study conducted from August to November 2019 at the Endoscopy Center of the Hospital Alemao Oswaldo Cruz (São Paulo, Brazil). The ethical committee of our institution (approval number 3.577.527) approved this research. It is in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Inclusion criteria were patients referred to routine diagnostic upper gastrointestinal endoscopy for dyspepsia symptoms who agreed to sign the informed consent form. Exclusion criteria were patients using proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) or H2 inhibitors in the last 10 d prior to endoscopy, patients with previous gastric surgeries (gastroplasty or gastrectomy), gastric stasis, hypertensive gastropathy, patients under 18 years of age, and non-elective indications (upper gastrointestinal bleeding, foreign body, etc.).

Baseline data that included age, gender, symptoms, medications, and previous H. pylori treatment were recorded.

The primary endpoint was to assess if NF-HD examination of gastric mucosal surface patterns could predict H. pylori status. The secondary endpoint was to assess if any other features observed with standard focus high definition (S-HD) white light examination was associated with H. pylori status.

All procedures were performed under anesthesiologist-assisted sedation with propofol. Before the procedures, every patient received a solution containing 200 mL of water and simethicone to help clean the stomach and improve visualization of the gastric mucosa. All examinations were performed with an Olympus CV-190 gastroscope. The images were captured by the BSCap™ system with a minimum of 10 photos, according to the European standard[19].

The examinations were performed by nine senior endoscopists (over 10 years of experience). Subsequently, two other endoscopists (Fiuza F and Martins BC), who had training on magnification imaging, reviewed all images and standardized the responses. Endoscopists who performed the exams had information about previous H. pylori infection. Fiuza F and Martins BC were blinded for previous and present H. pylori infection.

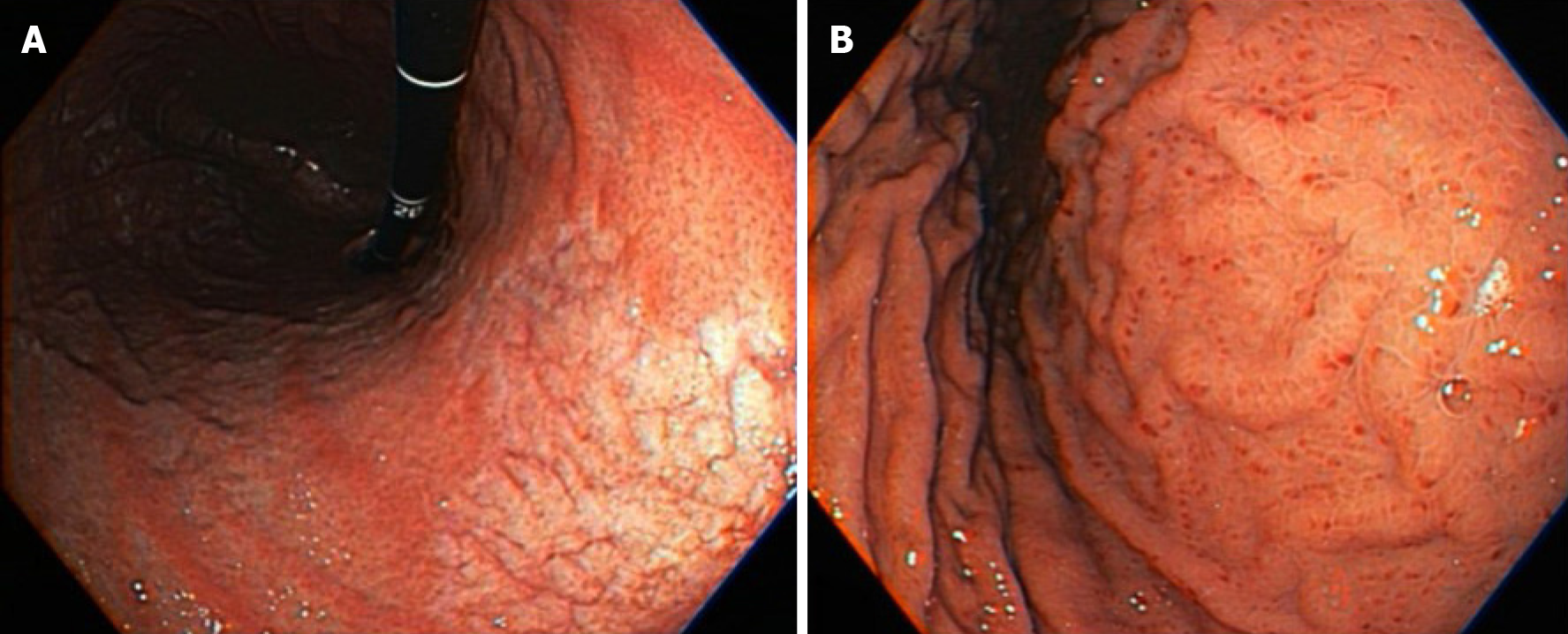

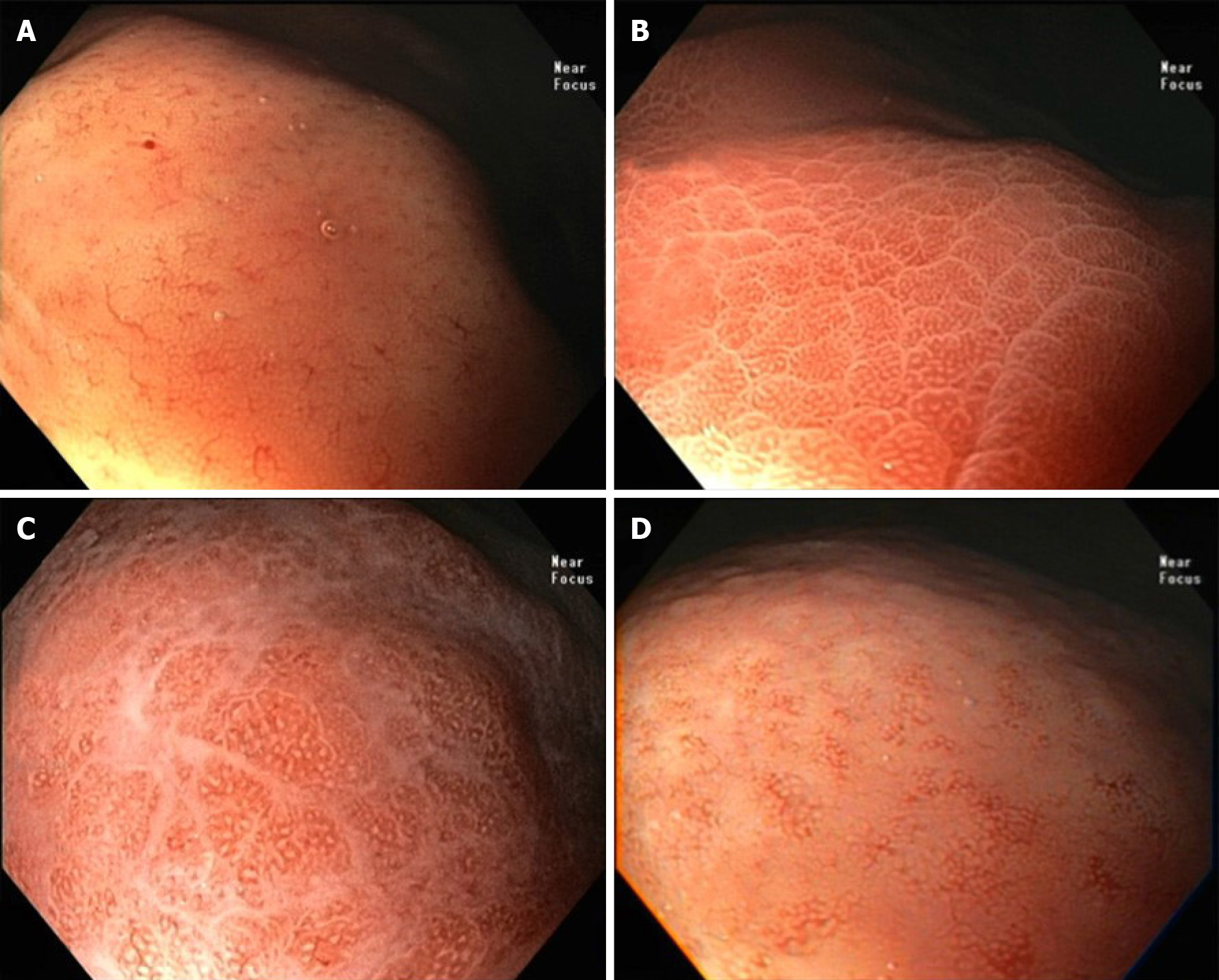

Initially, a complete exam was performed using S-HD white light view, and the characteristics of gastric mucosa were recorded: erythema, erosion, exudate, atrophy, and nodularity (Figure 1). Next, the near focus (NF-HD) exam was performed (Figure 2), with particular attention to the greater curvature and anterior wall of the medium gastric body, according to Yagi et al[9].

The gastric mucosal surface pattern was classified based on the classification proposed by Anagnostopoulos et al[10]: Type 1: Honeycomb-type subepithelial capillary network (SECN) with regular arrangement of collecting venules (RAC) and regular round pits; Type 2: Honeycomb-type SECN with regular round pits, with or without sulci but with loss of collecting venules; Type 3: Loss of normal SECN and collecting venules and with white enlarged pits surrounded by erythema; and Type 4: Loss of normal SECN and round pits, with irregular arrangement of collecting venules.

Gastric biopsies were collected for evaluation with the rapid urease test (RUT-Uretest®, RenyLab): One sample in the lesser curvature of the antrum close to the incisura angularis and the other in the greater curvature of the medium body. Next, gastric biopsies were collected for anatomopathological (AP) study: Two samples from the body and two from the antrum (greater and lesser curvature in each region), as oriented by the IV Brazilian Consensus on Helicobacter pylori Infection[3]. H. pylori infection was considered positive when at least one of the methods was positive.

Gastric biopsies were sent for histologic evaluation by a senior pathologist who was blinded from the endoscopic findings related to inflammation of gastric mucosa. Hematoxylin eosin staining was used for assessment of gastritis and Giemsa for H. pylori status. When gastritis was present at histology, but H. pylori was negative, immunohistochemical analysis for H. pylori antigen was performed.

Based on the results of previous studies[10,11,20], expecting a sensitivity of 94%, specificity of 95%, and a prevalence of infection of 40%, using an error margin of ± 6% and an alpha error of 5%, we estimated a sample size of 150 patients. Assuming a drop-out rate of 25%, the sample size was increased to 180 patients.

Measures of central tendency and dispersion were calculated for quantitative variables, as well as absolute and relative frequencies for categorical variables. The association between categorical variables was assessed using the chi-square test.

For the evaluation of the endoscopic diagnostic value, we estimated the sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), negative predictive value (NPV), area under the ROC curve and their respective 95% confidence intervals (CI) for the findings at S-HD and NF-HD. For all statistical tests, an alpha error of 5% was established, that is, the results were considered statistically significant when P < 0.05. All analyses were performed with Stata Software version 15.1.

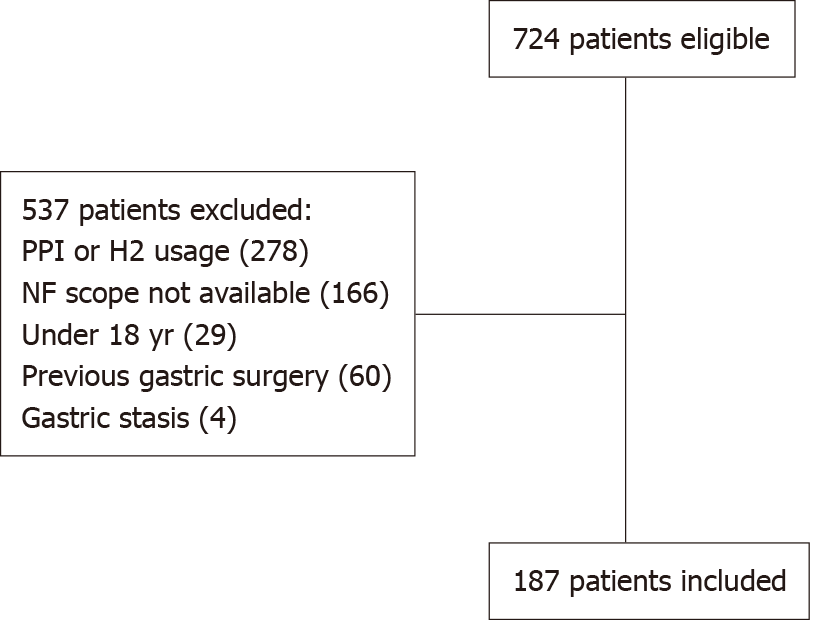

A total of 724 patients met the inclusion criteria and were eligible for this study. Five hundred thirty-seven patients were excluded: 278 due to PPI or H2 inhibitors usage in the previous 10 d, 166 due to NF endoscopes not available at the time of exam, 29 patients were under 18 years old, 60 due to previous gastric surgery, and 4 due to gastric stasis. Finally, 187 patients were included in the study (Figure 3). The majority of patients were female (60.5%), with a mean age of 50.1 years. Forty-two patients (22.5%) had been previously treated for H. pylori infection with an average interval of 48.2 mo (range 3-180 mo). The most prevalent symptom was epigastric pain (44.4%), followed by heartburn (21.4%). H. pylori was positive in 47 patients (25.1%), of which 42 were positive by both methods, four only by AP and one only by RUT (Table 1).

| Characteristics | Total (%) | H. pylori + (%) 47 (25.1%) | H. pylori-(%) 140 (74.9%) | P value |

| Age, yr | 0.580 | |||

| < 50 | 85 (45.5) | 23 (48.9) | 62 (44.3) | |

| > 50 | 102 (54.5) | 24 (51.1) | 78 (55.7) | |

| Gender | 0.629 | |||

| Male | 74 (39.5) | 20 (42.5) | 54 (38.6) | |

| Female | 113 (60.5) | 27 (57.5) | 86 (61.4) | |

| Symptoms | ||||

| Epigastric pain | 83 (44.4) | 26 (55.3) | 57 (40.7) | 0.081 |

| Heartburn | 40 (21.4) | 9 (19.1) | 31 (22.1) | 0.665 |

| Previous treated H. pylori infection | 42 (22.5) | 17 (36.2) | 25 (17.9) | 0.009 |

Upon initial examination of the gastric body with S-HD (Table 2), the finding with the best sensitivity for H. pylori detection was erythema (80.9%), present in 75 patients. Exudate (99.3%), nodularity (97.1%), and atrophy (95.7%) demonstrated better specificity values, but with low sensitivity (6.4%-19.1%). On the other hand, the absence of erythema on the gastric body was strongly associated with the absence of H. pylori infection (NPV = 92.0%).

| Location | Feature | Patients | Sensitivity % (95%CI) | Specificity % (95%CI) | PPV % (95%CI) | NPV % (95%CI) | AUC % (95%CI) | Accuracy % (95%CI) |

| Body | Erythema | 75 | 80.9 (66.7-90.9) | 73.6 (65.5-80.7) | 50.7 (38.9-62.4) | 92.0 (85.3-62.4) | 0.77 (0.70-0.84) | 75.4 (68.6-81.4) |

| Erosion | 16 | 10.6 (3.6-23.1) | 92.1 (86.4-96.0) | 31.3 (11.0-58.7) | 75.4 (68.3-81.7) | 0.51 (0.46-0.56) | 71.7 (64.6-78.0) | |

| Exudate | 4 | 6.4 (1.3-17.5) | 99.3 (96.1-100) | 75.0 (19.4-99.4) | 76.0 (69.1-82.0) | 0.53 (0.49-0.56) | 75.9 (69.2-81.9) | |

| Atrophy | 15 | 19.1 (9.1-33.3) | 95.7 (90.9-98.4) | 60.0 (71.0-83.9) | 77.9 (71.0-83.9) | 0.57 (0.52-0.63) | 76.5 (69.7-82.3) | |

| Nodularity | 7 | 6.4 (1.3-17.5) | 97.1 (92.8-99.2) | 42.9 (9.9-81.6) | 75.6 (68.6-81.6) | 0.52 (0.48-0.56) | 74.3 (67.4-80.4) | |

| Antrum | Erythema | 87 | 72.3 (57.4-84.4) | 62.1 (53.6-70.2) | 39.1 (28.8-50.1) | 87.0 (78.8-92.9) | 0.67 (0.60-0.75) | 64.7 (57.4-71.5) |

| Erosion | 38 | 21.3 (10.7-35.7) | 80.0 (72.4-86.3) | 26.3 (13.4-43.1) | 75.2 (67.4-81.9) | 0.51 (0.44-0.57) | 65.2 (57.9-72.0) | |

| Exudate | 1 | 2.1 (0.5-11.3) | 100 (97.4-100) | 100 (2.5-100) | 75.3 (68.4-81.3) | 0.51 (0.49-0.53) | 75.4 (68.6-81.4) | |

| Atrophy | 16 | 23.4 (12.3-38.0) | 96.4 (91.9-98.8) | 68.8 (41.3-89.0) | 78.9 (72.1-84.8) | 0.60 (0.54-0.66) | 78.1 (71.4-83.8) | |

| Nodularity | 7 | 10.6 (3.5-23.1) | 98.6 (94.9-99.8) | 71.4 (29.0-96.3) | 76.7 (69.8-82.6) | 0.55 (0.50-0.59) | 76.5 (69.7-82.3) |

In the antrum, all findings showed sensitivity below 75% (Table 2). Nodularity (98.6%) and atrophy (96.4%) had the best values for specificity, but both had low sensitivities (10.6%-23.4%). Exudate, although presenting with 100% specificity, was found in only one patient.

With the use of NF (Table 3), the majority of patients presented with a type 1 pattern (56.2%), followed by type 2 (30.5%), type 3 (9.6%), and type 4 (3.7%). Type 1 pattern is the only one in which RAC is seen. Only six patients (5.7%) with RAC + were H. pylori positive. The loss of RAC presented with a sensitivity of 87.2% for H. pylori detection and a NPV of 94.3%, indicating that H. pylori infection was less likely when RAC was seen. All patients with type 4 pattern were H. pylori positive (PPV of 100%), albeit only seven patients presented with this pattern. Among patients with successful previous H. pylori treatment (n = 25), 21 (91.3%) were RAC positive (Table 4). Loss of RAC had a NPV of 91.3%, specificity of 84%, and an accuracy of 85.7% (Table 5).

| RAC | Classification | Helicobacter pylori status (%) | Total (%) | |

| Negative | Positive | |||

| RAC + | ||||

| Type 1 | 99 (94.3) | 6.0 (5.7) | 105 (56.2) | |

| RAC - | ||||

| Type 2 | 35 (61.4) | 22 (38.6) | 57 (30.5) | |

| Type 3 | 6 (33.3) | 12 (66.7) | 18 (9.6) | |

| Type 4 | 0 (0.0) | 7 (100.0) | 7 (3.7) | |

| Types 2, 3 and 4 | 41 (50) | 41 (50) | 82 (43.8) | |

| Total | 140 (74.9) | 47 (25.1) | 187 (100) | |

| Classification | Helicobacter pylori status (%) | Total (%) | |

| Negative | Positive | ||

| RAC + | 21 (91.3) | 2 (8.7) | 23 (54.8) |

| RAC - | 4 (21.1) | 15 (78.9) | 19 (45.2) |

| Total | 25 (59.5) | 17 (40.5) | 42 (100) |

| Loss of RAC | Sensitivity% (95%CI) | Specificity% (95%CI) | PPV % (95%CI) | NPV % (95%CI) | AUC % (95%CI) | Accuracy % (95%CI) |

| Overall (n = 187) | 87.2 (74.3-95.2) | 70.7 (62.4-78.1) | 50.0 (38.7-61.3) | 94.3 (88.0-97.9) | 0.79 (0.73-0.85) | 74.5 (67.6-80.5) |

| Patients without previous Helicobacter pylori treatment (n = 145) | 86.7 (69.3-96.2) | 67.8 (58.5-76.2) | 41.3 (29.0-54.4) | 95.1 (88.0-98.7) | 0.77 (0.69-0.85) | 71.7 (63.6-78.9) |

| Patients with previous Helicobacter pylori treatment (n = 42) | 88.2 (63.6-98.5) | 84.0 (63.9-95.5) | 78.9 (54.4-93.9) | 91.3 (72.0-98.9) | 0.86 (0.73-0.97) | 85.7 (71.5-94.6) |

Four patients had RUT negative, but AP positive, and one patient had RUT positive and AP negative. Thus, RUT presented with a sensitivity of 91.5%, specificity of 100%, PPV of 100%, NPV of 97.2%, and accuracy of 97.9%.

An endoscopic mucosal sample is the most common method used for H. pylori detection. However, it generates costs associated with biopsy forceps, reagent agents, vials, and pathologists, in addition to the risk of bleeding and other complications. Thus, a diagnostic method that excludes the need for large-scale biopsies with good cost-effectiveness is welcome both economically and logistically.

In 2002, Yagi et al[11] described the magnified view of H. pylori negative gastric mucosa and showed that the identification of collecting venules and capillaries forming a network with gastric pits in the center is indicative of H. pylori-negative normal mucosa. This pattern was named RAC. In a study with 557 patients submitted to endoscopy, the same authors demonstrated that the presence of RAC had a sensitivity of 93.6% and specificity of 96.2% as an indicator of a normal stomach without H. pylori[11]. Similar findings were reported by Anagnostopoulos et al[10], in a study including 95 patients in a Western population. The authors applied ME in the gastric body and showed that type 1 pattern predicted normal gastric mucosa with a sensitivity of 92.7%, specificity of 100%, PPV of 100%, and NPV of 83.8%. However, magnification is time-consuming, requires training, and is not widely available in western centers. Therefore, the use of NF becomes an alternative due to its feasibility and availability.

In this study, we evaluated near-focus imaging for the diagnosis of H. pylori status of gastric mucosa. We showed that the loss of RAC had a sensitivity of 87% for detection of H. pylori and a NPV of 94.3%. Only six patients with RAC + were positive for H. pylori. In other words, if RAC was present, the probability of a H. pylori negative mucosa was 94.3%. In a prospective study with 140 patients, Garcés-Durán et al[14] used Olympus 190 gastroscopes to evaluate if the presence of RAC could rule out H. pylori infection in a western population. The authors did not mention if they applied NF to examine the gastric mucosa, so it is assumed that only S-HD exam was performed. The authors found a sensitivity and NPV of 100% for the exclusion of H. pylori infection in RAC+ patients. In a congress report communication, Jang et al[18] compared NF + NBI with SD-WL for predicting H. pylori status. The sensitivity, specificity, PPV, and NPV were 86.5%, 84.1%, 84.1%, and 88.3% for NF + NBI and 57.7%, 92.1%, 53.0%, and 72.5% for SD-WL endoscopy, respectively. In a pediatric population (children and adolescents) using standard endoscopes, Machado et al16 demonstrated that the absence of RAC had a sensitivity of 96.9% and a specificity of 88.1% in predicting H. pylori infection. Glover et al[21] showed that RAC becomes less visible with increasing age, presenting NVP of 93.0% for patients below 50 years and NVP of 90.7% for all ages. Table 6 shows a comparison between studies that addressed the association of RAC with H. pylori status. On the other hand, loss of RAC was present in 49/96 (51%) H. pylori negative patients in the study of Garcés-Durán et al[14], while in our study, loss of RAC was present in 41/140 (29%) H. pylori negative patients. This difference could be explained by the use of NF in our study. NF increased the sensitivity to identify capillary venules. Therefore, NF-HD resulted in increased specificity but decreased sensitivity for H. pylori detection applying the “loss of RAC” signal.

| Ref. | Country | n | RAC + | Technology | Sensitivity | Specificity | PPV | NPV |

| Machado et al[16], 2008 | Brazil | 99 | 60 | SD | 96.9 | 88.1 | - | - |

| Cho et al[15], 2013 | Korea | 617 | 254 | S-HD | 93.3 | 89.1 | 92. | 90.6 |

| Yagi et al[17], 2014 | Japan | 38 | 26 | S-HD | 79 | 52 | 70 | 63 |

| Garcés-Durán et al[14], 2019 | Spain | 140 | 47 | S-HD | 100 | 48.9 | 47.3 | 100 |

| Ebigbo et al[22], 2021 | German | 200 | - | S-HD | 80.7 | 57.4 | 40.0 | 89.4 |

| Glover et al[21], 2021 | United Kingdom | 153 | 108 | S-HD | 78.4 | 64.3 | 40.0 | 90.7 |

| Jang et al[18], 2020 | Korea | 115 | - | NF + NBI | 86.5 | 84.1 | 84.1 | 88.3 |

| Yagi et al[11], 2002 | Japan | 557 | 161 | ME | 93.8 | 96.2 | - | - |

| Nakagawa et al[12], 2003 | Japan | 92 | 23 | ME | 66.7 | 100 | 100 | 82.4 |

| Anagnostopoulos et al[10], 2007 | United Kingdom | 95 | 64 | ME | 100 | 92.7 | 83.8 | 100 |

| Yagi et al[17], 2014 | Japan | 49 | 30 | ME + NBI | 91 | 83 | 88 | 86 |

| This study | Brazil | 187 | 105 | NF | 87.2 | 70.7 | 50.0 | 94.3 |

Although RAC identification with HD endoscopes has good accuracy to screen H. pylori negative patients, it seems that the loss of RAC is not so specific to confirm H. pylori infection. In this study, the loss of RAC was associated with H. pylori infection in only 50.6% (41/81) of the cases, with a PPV of 50%. These findings are in accordance with other studies where RAC negative patients presented H. pylori infection in 40-47.3% of patients[14,21,22]. With ME, Anagnostopoulos et al[10] presented that types 2 and 3 together had a specificity of 92.7% and PPV of 83.8% for predicting H. pylori infection.

Taken together, sensitivity of “loss of RAC” to predict H. pylori infection varied from 66% to 100% and specificity varied from 48% to 100%. Excluding the studies that used ME, the one with higher sensitivity was also the one with lower specificity[14]. The wide variability of sensitivity and specificity of RAC identification and H. pylori status among studies might be explained by different technology applied and different endoscopists’ expertise. Apparently, there is lower variability of NPV among studies, meaning that the presence of RAC is a good indicator of H. pylori negative status.

Besides RAC, the best S-HD criteria to screen for H. pylori negative patients in this study was erythema, with NPV of 92%. The sensitivity of erythema for H. pylori detection was 80.9%, specificity 73.6%, and PPV 50.7%. Exudate, atrophy, and nodularity were the most specific findings. In a multicenter study including 24 facilities in Japan, Kato et al[23] studied the association of body erythema and H. pylori infection with S-HD. Spotty redness had sensitivity of 70.3%, specificity of 73.8, PPV of 75%, and NPV of 69.1%; diffuse redness, sensitivity of 83.4%, specificity of 66.9, PPV of 73.8%, and NPV of 78.4%. Machado et al[16] highlighted nodularity in children and adolescents as a strong predictor of H. pylori infection (98.5%). Absence of nodularity was associated with the presence of RAC, virtually excluding the probability of H. pylori (post-test probability 0.78%). In a series of 200 gastroscopic examination with S-HD[22], the presence of RAC and the Kimura-Takemoto classification grade C1 were predictive of H. pylori negative status, while atrophic changes and diffuse redness without RAC were significantly associated with H. pylori infection.

The awareness of these findings may lead endoscopists to change some practices during elective routine endoscopy. For example, many patients may be referred to endoscopy while using continuous PPI, which is known to decrease sensitivity of RUT and AP tests[3]. In this sense, findings of diffuse erythema, atrophy, or exudate on white light examination, as well as loss of RAC on NF exam, may lead the endoscopist to use more resources to increase the yield of H. pylori detection. This may include collecting more fragments and/or performing biopsies for histopathological analysis besides RUT. We also believe that a closer look at the mucosa must be routinely incorporated in elective upper endoscopy in order to look for the mucosal surface pattern. It is quick and easy to apply.

The reversal of mucosal changes after H. pylori eradication is still poorly understood. In this study, the accuracy of RAC pattern to predict H. pylori status in the group of patients with previous H. pylori treatment was 85.7% (95%CI: 71.5-94.6) compared with 71.1% (95%CI: 63.6-78.9) to the non-treated group. PPV was higher (78.9%; 95%CI: 54.4-93.9 vs 41.3%; 95%CI: 29.0-54.4), and NPV was similar (91.3; 95%CI: 72.0-98.9 vs 95.1%; 95%CI: 88.0-98.7). These findings could indicate that mucosal changes might be reversible in some cases.

Our study has some limitations. First, it is a single-institution study. It would be important to evaluate the interobserver agreement and to validate these findings in a multicenter study. On the other hand, our study supports the concept of first screening patients for the presence of RAC and deferring biopsy in patients positive for RAC.

In conclusion, the presence of RAC at the NF-HD exam and the absence of erythema in the gastric body at S-HD were predictive of H. pylori negative status. On the other hand, the loss of RAC had a poor association with the presence of H. pylori.

In recent years, many advances in endoscopic imaging have surged, allowing for better characterization of gastric mucosal patterns. In 2001, Yao and Oishi described the characteristics of normal gastric mucosa with image magnification (ME). In the following year, Yagi et al described the differences between the magnified view of normal gastric mucosa from the pattern seen in patients with Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori)-associated gastritis. Although there are many studies correlating the findings of ME and H. pylori status, only a few validated these findings with high definition (HD) endoscopes without ME. Moreover, most of these studies were conducted in Asian countries, in centers with high expertise with magnifying images.

While magnification endoscopy is well incorporated in Asian countries, in Western countries most upper endoscopes devices are not equipped with this feature.

The aim of this study is to access the association between mucosal surface pattern under near focus HD (NF-HD) technology and H. pylori infection status in a western population.

This was a cross-sectional study including all patients referred to routine upper endoscopy. Endoscopic exams were performed using standard HD (S-HD) followed by NF-HD examination. Presence of erythema , erosion, atrophy, and nodularity were recorded during S-HD, and surface mucosal pattern was classified using NF-HD in the gastric body, based on the classification proposed by Anagnostopoulos et al. Biopsies were taken for rapid urease test and histology.

One hundred and eighty-seven patients were included in the study, of those, 47 (25.1%) were H. pylori +. In the examination with S-HD, erythema had the best sensitivity for H. pylori detection (80.9%). On the other hand, the absence of erythema was strongly associated with H. pylori- (negative predictive value = 92%). With NF-HD, the loss of the regular arrangement of collecting venules (RAC) presented 87.2% sensitivity for H. pylori detection and 94.3% negative predictive value, indicating that loss of RAC was suboptimal to confirm H. pylori infection, but when RAC was seen, H. pylori infection was unlikely.

Presence of RAC at the NF-HD exam and the absence of erythema in the gastric body at S-HD were predictive of H. pylori negative status. The loss of RAC had a poor association with the presence of H. pylori.

Our study supports the concept of first screening patients for the presence of RAC and deferring biopsy in patients positive for RAC.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: Brazil

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Apiratwarakul K, Oda M, Yang X S-Editor: Gao CC L-Editor: A P-Editor: Liu JH

| 1. | Correa P, Piazuelo MB. The gastric precancerous cascade. J Dig Dis. 2012;13:2-9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 355] [Cited by in RCA: 520] [Article Influence: 40.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Dinis-Ribeiro M, Areia M, de Vries AC, Marcos-Pinto R, Monteiro-Soares M, O'Connor A, Pereira C, Pimentel-Nunes P, Correia R, Ensari A, Dumonceau JM, Machado JC, Macedo G, Malfertheiner P, Matysiak-Budnik T, Megraud F, Miki K, O'Morain C, Peek RM, Ponchon T, Ristimaki A, Rembacken B, Carneiro F, Kuipers EJ; European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy; European Helicobacter Study Group; European Society of Pathology; Sociedade Portuguesa de Endoscopia Digestiva. Management of precancerous conditions and lesions in the stomach (MAPS): guideline from the European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE), European Helicobacter Study Group (EHSG), European Society of Pathology (ESP), and the Sociedade Portuguesa de Endoscopia Digestiva (SPED). Endoscopy. 2012;44:74-94. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 442] [Cited by in RCA: 489] [Article Influence: 37.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Coelho LGV, Marinho JR, Genta R, Ribeiro LT, Passos MDCF, Zaterka S, Assumpção PP, Barbosa AJA, Barbuti R, Braga LL, Breyer H, Carvalhaes A, Chinzon D, Cury M, Domingues G, Jorge JL, Maguilnik I, Marinho FP, Moraes-Filho JP, Parente JML, Paula-E-Silva CM, Pedrazzoli-Júnior J, Ramos AFP, Seidler H, Spinelli JN, Zir JV. IVTH brazilian consensus conference on helicobacter pylori infection. Arq Gastroenterol. 2018;55:97-121. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Uemura N, Okamoto S, Yamamoto S, Matsumura N, Yamaguchi S, Yamakido M, Taniyama K, Sasaki N, Schlemper RJ. Helicobacter pylori infection and the development of gastric cancer. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:784-789. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3126] [Cited by in RCA: 3182] [Article Influence: 132.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Ford AC, Forman D, Hunt RH, Yuan Y, Moayyedi P. Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy to prevent gastric cancer in healthy asymptomatic infected individuals: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ. 2014;348:g3174. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 456] [Cited by in RCA: 442] [Article Influence: 40.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 6. | Chen HN, Wang Z, Li X, Zhou ZG. Helicobacter pylori eradication cannot reduce the risk of gastric cancer in patients with intestinal metaplasia and dysplasia: evidence from a meta-analysis. Gastric Cancer. 2016;19:166-175. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 139] [Cited by in RCA: 163] [Article Influence: 18.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Chai NL, Ling-Hu EQ, Morita Y, Obata D, Toyonaga T, Azuma T, Wu BY. Magnifying endoscopy in upper gastroenterology for assessing lesions before completing endoscopic removal. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:1295-1307. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 8. | Yao K, Oishi T. Microgastroscopic findings of mucosal microvascular architecture as visualized by magnifyin endoscopy. Dig Endosc. 2001;13:27-33. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Yagi K, Nakamura A, Sekine A. Comparison between magnifying endoscopy and histological, culture and urease test findings from the gastric mucosa of the corpus. Endoscopy. 2002;34:376-381. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Anagnostopoulos GK, Yao K, Kaye P, Fogden E, Fortun P, Shonde A, Foley S, Sunil S, Atherton JJ, Hawkey C, Ragunath K. High-resolution magnification endoscopy can reliably identify normal gastric mucosa, Helicobacter pylori-associated gastritis, and gastric atrophy. Endoscopy. 2007;39:202-207. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 109] [Cited by in RCA: 113] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Yagi K, Nakamura A, Sekine A. Characteristic endoscopic and magnified endoscopic findings in the normal stomach without Helicobacter pylori infection. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2002;17:39-45. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 123] [Cited by in RCA: 130] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Nakagawa S, Kato M, Shimizu Y, Nakagawa M, Yamamoto J, Luis PA, Kodaira J, Kawarasaki M, Takeda H, Sugiyama T, Asaka M. Relationship between histopathologic gastritis and mucosal microvascularity: observations with magnifying endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;58:71-75. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Jang HY, Hong SJ, Han JP, Park SK, Yun HK, Ko BJ. Comparison of the Diagnostic Usefulness of Conventional Magnification and Near-focus Methods with Narrow-band Imaging for Gastric Epithelial Tumors. Korean J Helicobacter Up Gastrointest Res. 2015;15:39. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Garcés-Durán R, García-Rodríguez A, Córdova H, Cuatrecasas M, Ginès À, González-Suárez B, Araujo I, Llach J, Fernández-Esparrach G. Association between a regular arrangement of collecting venules and absence of Helicobacter pylori infection in a European population. Gastrointest Endosc. 2019;90:461-466. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Cho JH, Chang YW, Jang JY, Shim JJ, Lee CK, Dong SH, Kim HJ, Kim BH, Lee TH, Cho JY. Close observation of gastric mucosal pattern by standard endoscopy can predict Helicobacter pylori infection status. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;28:279-284. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 16. | Machado RS, Viriato A, Kawakami E, Patrício FR. The regular arrangement of collecting venules pattern evaluated by standard endoscope and the absence of antrum nodularity are highly indicative of Helicobacter pylori uninfected gastric mucosa. Dig Liver Dis. 2008;40:68-72. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Yagi K, Saka A, Nozawa Y, Nakamura A. Prediction of Helicobacter pylori status by conventional endoscopy, narrow-band imaging magnifying endoscopy in stomach after endoscopic resection of gastric cancer. Helicobacter. 2014;19:111-115. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Jang JY, Baek S, Ryu B, Park YM, Oh CH, Kim JW. Usefulness of Near-Focus magnification with Narrow-Band Imaging in the prediction of helicobacter pylori infection: a prospective trial. Gastrointest Endosc. 2020;91:AB242-AB243. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Bisschops R, Areia M, Coron E, Dobru D, Kaskas B, Kuvaev R, Pech O, Ragunath K, Weusten B, Familiari P, Domagk D, Valori R, Kaminski MF, Spada C, Bretthauer M, Bennett C, Senore C, Dinis-Ribeiro M, Rutter MD. Performance measures for upper gastrointestinal endoscopy: a European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Quality Improvement Initiative. Endoscopy. 2016;48:843-864. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 252] [Cited by in RCA: 239] [Article Influence: 26.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Gonen C, Simsek I, Sarioglu S, Akpinar H. Comparison of high resolution magnifying endoscopy and standard videoendoscopy for the diagnosis of Helicobacter pylori gastritis in routine clinical practice: a prospective study. Helicobacter. 2009;14:12-21. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Glover B, Teare J, Patel N. Assessment of Helicobacter pylori status by examination of gastric mucosal patterns: diagnostic accuracy of white-light endoscopy and narrow-band imaging. BMJ Open Gastroenterol. 2021;8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Ebigbo A, Marienhagen J, Messmann H. Regular arrangement of collecting venules and the Kimura-Takemoto classification for the endoscopic diagnosis of Helicobacter pylori infection: Evaluation in a Western setting. Dig Endosc. 2021;33:587-591. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Kato T, Yagi N, Kamada T, Shimbo T, Watanabe H, Ida K; Study Group for Establishing Endoscopic Diagnosis of Chronic Gastritis. Diagnosis of Helicobacter pylori infection in gastric mucosa by endoscopic features: a multicenter prospective study. Dig Endosc. 2013;25:508-518. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 88] [Cited by in RCA: 103] [Article Influence: 8.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |